Glasgow G12 8QQ Time, Then Herodotus Would Surely Have

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Ionian Revolt to Marathon

2/26/2012 Lecture 11: Ionian Revolt to Marathon HIST 332 Spring 2012 Life for Greek poleis under Cyrus • Cyrus sent messages to the Ionians asking them to revolt against Lydian rule – Ionians refused After conquest: • Ionian cities offered to be Persian subjects under the same terms – Cyrus refused, citing the Ionians’ unwillingness to help – Median general Harpagus sent to conquer Ionia – Installed tyrants to rule for Persia Ionian Revolt (499-494 BCE) 499 Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletos wants to attack Naxos • He can’t pay for it – so persuades satrap to invade – The invasion fails • Aristogoras needs to repay Persians • leads rebellion against Persian tyrants • He goes to Greece to ask for help – Sparta refuses – Athens sends a fleet 1 2/26/2012 Cleomenes’ reply to Aristagoras • Aristagoras goes to Sparta to solicit help – tells King Cleomenes that the “Great King” lived three months from the sea (i.e. easy task) “Get out of Sparta before sundown, Milesian stranger, for you have no speech eloquent enough to induce the Lacedemonians to march for three months inland from the sea.” -Herodotus, Histories 5.50 Ionian Rebellion Against Persia Ionian cities rebel 498 Greeks from Ionia attempt to take Satrap capital of Sardis – fire breaks out • Temple of Ahura-Mazda is burned • Battle of Ephesus – Greeks routed 497-5 Persian Counter-Attack – Cyprus taken – Hellespont pacified 494 Sack of Miletus Satrap installs democracies in place of tyrannies Darius not pleased with the Greeks • Motives obscure – punishment of Athenian aid to Ionians – was -

An Honor to Bear

The Pheidippides Legend An Honor to Bear Published in Marathon and Beyond Magazine, April 2002 A Short Story, Based on History and Legend: The Soldier/Runner Had One Last Task to Perform Before He Could Rest. By Kenneth W. Williams PHEIDIPPIDES FORCED himself to stir. Just to move required supreme effort. He was amazed at the force of the arrow that stuck him and knocked him to the dust. In actuality, the arrow had done little more than graze his arm, but the force of that glancing blow spun him and threw him to the ground. Stunned, he contemplated the physics behind the event while he tried to regain his footing and resume his charge toward the Persians. It was such a foolish thing to be thinking about while Persian arrows flew all round him, but one’s mind can do such strange things in battle. The little olive tree under which he now rested offered precious little shade from the relentless sun. He shifted, in search of a position that allowed his weary body a moment’s rest. His weariness was bone-deep, born of too many miles in too few days. His hands were still stained with blood from the recent carnage. It was hot—far hotter than it should be in the middle of September. His armor—helmet; shield, breastplate, and greaves—attracted and magnified the rays of the fierce sun. September was always a hot month in Greece, but this year it was ever hotter than usual. The gentle breeze from the nearby Aegean did not help. -

Fighting the Persian Wars

CHAPTER 4 This painted pottery bowl portrays the defeat of a Persian soldier by a Greek soldier. Fighting the Persian Wars 28.1 Introduction In Chapter 27, you learned about two very different city-states, Athens and Sparta. Sometimes their differences led these city-states to distrust each other. But between 499 and 479 B.C.E., they had a common enemy—the Persian Empire. At the time, Persia was the largest empire the world had ever seen. Its powerful kings ruled over land in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. During the 400s B.C.E., the Persians invaded Greece, and the Persian wars began. To fight the Persians, the Greek city-states eventually banded together as allies. Allies are states that agree to help each other against a common enemy. Throughout history, soldiers have written home before bat- Persian soldier tle. We can image the kind of letter an Athenian might have written to his family. "The Greek soldier Persians are fierce fighters. But I will stand shoulder to shoulder with the brave men of Greece—Spartans as well as fellow Athenians—and fight to the death, if that is what it takes to stop these murderous invaders." The tiny Greek city-states had much less land and far fewer people than Persia. How could they possibly turn back the powerful invaders? In this chapter, you will learn about Use this graphic organizer to help you understand how the important battles during the Greek city-states banded together to fight the powerful Persian wars and discover who Persian Empire. -

Ionian Revolt (499-494 BCE)

4/12/2012 Lecture 24: Greeks Tame the Hydra HIST 213 Spring 2012 Chronology of Persian-Greek Interaction 550 Ionian Greeks under Persian rule 499-4 Ionian Rebellion 490 Darius invades Greece – Battle of Marathon 480 Xerxes Invades Greece – Battles of Salamis and Plataea 448 Peace Treaty between Persia and Greece 407 Persians fund Spartan fleet 401 Anabasis of Xenophon 396-5 Invasion of Asia Minor by Agesilaos 395 Persians fund Social War in Greece 350 Philip II of Macedonia calls for “crusade” against Persia Ionian Revolt (499-494 BCE) 499 Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletos wants to attack Naxos • He can’t pay for it – so persuades satrap to invade – The invasion fails • Aristogoras needs to repay Persians • leads rebellion against Persian tyrants • He goes to Greece to ask for help – Sparta refuses – Athens sends a fleet 1 4/12/2012 Ionian Rebellion Against Persia Ionian cities rebel 498 Greeks from Ionia attempt to take Satrap capital of Sardis – fire breaks out • Temple of Ahura-Mazda is burned • Battle of Ephesus – Greeks routed 497-5 Persian Counter-Attack – Cyprus taken – Hellespont pacified 494 Sack of Miletus Satrap installs democracies in place of tyrannies Darius not pleased with the Greeks • Motives obscure – punishment of Athenian aid to Ionians – was going to conquer it anyway • fleet and army prepared to sail to Attica and Eretria • Approaches former Athenian tyrant Hippias 2 4/12/2012 Persian Wars Three Phases: Phase I: 490s 492 Persian fleet destroyed at Athos 490 Battle of Marathon Phase II 480 BCE August Battle of Thermopylae/Artemisium Sept Persians occupy Athens – Athens burned Battle of Salamis (naval) – Greeks Win Phase III 479 BCE 479 Battle of Plataea First Persian Invasion (492) Mardonios led the Persian Army across the Hellespont into Thrace and Macedonia Athens and Eretria are assumed to have been targets Persian fleet is destroyed off the Chalcidice near Mt. -

Battle of Marathon

LO: To retell the events of The Battle of Marathon. Battle of Marathon Athens & Sparta What can you re-call from last lesson? Persia • The Persian King (King Darius) decided he wanted to take over Greece. • It often attacked Greek colonies • Athens often sent soldiers to help them. • The Greeks were unable to stop the Persian armies when they decided to attack. Who might the Athenians ask for help? Spartans were highly regarded as epic warriors Sparta and Athens decided to join together to fight the Persians. Battle Commences! • In 492 BC, King Darius of Persia ordered the Greeks to obey him. • In 490 BC he travelled with his army to fight at the Bay of Marathon – this fight is known as the Battle of Marathon. Pheidippides As soon as the Athenians realised the Persians were coming to attack Greece, they sent a fast runner called Pheidippides, to run all the way to Sparta to ask for help But the Spartans were celebrating a religious festival and would not come until the next full moon. But then..... One of the Athenian officers had a clever plan. A plan that had never been used before. Would it work? The Athenians attacked! They came from the sides! The Persians could not believe it! They got confused, they broke the ranks and gave the Athenians the chance to get behind them. The Persian army was defeated! The Persians fled to their ships and left. They lost more than 6000 men. The Athenians only lost 192. The Spartans were amazed that the small Athenian army could defeat that enormous and powerful Persian army. -

The Greek Histories

The Greek Histories Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 The Greek Histories Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Companion to Greeks: The Histories, a great books curriculum by Roman Roads Media. The Greek Histories: Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Old Western Culture Reader, Volume 3. Copyright © 2018 Roman Roads Media Published by Roman Roads Media, LLC 121 E 3rd St., Moscow ID 83843 www.romanroadsmedia.com [email protected] Editor: Evan Gunn Wilson Series Editor: Daniel Foucachon Cover Design: Valerie Anne Bost and Rachel Rosales Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by the USA copyright law. Version 1.0.0 The Greek Histories: Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon Old Western Culture Reader Vol. 3 Roman Roads Media, LLC. ISBN: 978-1-944482-33-6 This is a companion reader for the Old Western Culture curriculum by Roman Roads Media. To find out more about this course, visit www.romanroadsmedia.com Old Western Culture Great Books Reader Series THE GREEKS The Epics Drama & Lyric The Histories The Philosophers THE ROMANS The Aeneid The Historians Early Christianity Nicene Christianity CHRISTENDOM Early Medievals Defense of the Faith The Medieval Mind The Reformation EARLY MODERNS Rise of England The Enlightenment The Victorian Poets The Novels Copyright © 2018 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 121 E 3rd St Moscow, Idaho 83843 www.romanroadsmedia.com Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. -

The Persian Wars

The Persian Wars The Limits of Empire And the Birth of a Greek World View Median Empire • Cyaxares: – Attacks Lydia in 590 BC. – On 28 May 585 BC. the war ends. • Astyages (585-550 BC.) – Married Aryenis in 585 BC. – Gave Mandane to Cambyses I before 580 BC. – Deserted by his troops and defeated by his grandson, Cyrus, in 550 BC. Cyrus the Great • King of Anshan in 560 BC. • Attacked Media in 550 BC. • Defeated Croesus of Lydia in 547/6 BC. • Defeated Babylon in 539 BC. • Died in 530 BC. attacking the Massagetae The Persian Empire Cambyses • King of Babylon by 27 March, 538 BC. • Great King in Sept, 530. • Invaded Egypt in 525. • Cambyses was “not in his right mind, but mad” (Hdt.3.25). • Died accidentally in 522 BC. • Succeeded by Smerdis, March 522 • Smerdis killed September 522 BC Darius I • Two years of rebellions: consolidated power by 520 BC. • Reorganization into 20 satrapies • Invaded Scythia via Europe in 513 • Satrapy in Europe, Skudra (Thrace) • Construction of Persepolis • 507: Accepted ‘Earth and Water’ from Athens. Empire of Darius I Persia in the Aegean The Ionian Revolt • Aristagoras, Tyrant of Cyzicus and Miletus – Convinced Persians to invade Naxos – Four month siege failed in 499 – Aristagoras and Histiaeus launch revolt of the Ionians Ionian Revolt • Cleomenes refused to participate • Athens contributed 20 ships – “Perhaps it is easier to fool a crowd…” (Hdt. V.97). – Sardis sacked, the temple of Cybele burned. – Ionian army defeated near Ephesus – Athenian aid withdrawn – Aristagoras killed in Thrace Ionian Revolt Persian Response • 498 • Took Byzantium, Chalcedon, the Troad, Lamponium, Lemnos and Imbros – Defeated the Ionian army at Ephesus – Took Clazomenae and Cyme • 497-494 – Besieged Miletus and campaigned in that area • 494 BC. -

“The First Thing the Generals Did, While Still in the City, Was to Send A

ΔΙΕΘΝΗΣ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΟΣ ΑΓΩΝΑΣ ΥΠΕΡΑΠΟΣΤΑΣΕΩΝ . ΑΘΗΝΑ-ΣΠΑΡΤΗ 246ΧΛΜ “The first thing the generals did, while still in the city, was to send a message to Sparta by dispatching a herald named Pheidippides, who was an Athenian long-distance runner and a professional in this work. …So after Pheidippides had been sent off by the generals and, as he claimed, Pan had appeared to him, he arrived in Sparta on the day after he had left Athens.” Herodotus, 6.105-6.106 INTERNATIONAL HISTORIC ULTRA-DISTANCE RACE . ATHENS-SPARTA 246K SPARTATHLON is a historic ultra-distance Το ΣΠΑΡΤΑΘΛΟΝ είναι ένας ιστορικός foot race that takes place at the end of υπερμαραθώνιος που λαμβάνει χώρα September of every year in Greece. The race στο τέλος του Σεπτέμβρη κάθε χρόνο revives the footsteps of Pheidippides, an an- στην Ελλάδα. Ο αγώνας αναβιώνει τα cient Athenian long distance runner, who, in βήματα του Φειδιππίδη, ενός αρχαίου ΑΠΟΚΛΕΙΣΤΙΚΟΣ ΔΩΡΗΤΗΣ 490 BC before the battle of Marathon, was Αθηναίου δρομέα μεγάλων αποστάσεων, ο οποίος το 490 π.Χ., πριν από τη μάχη sent to Sparta to seek help in the war against EXCLUSIVE SPONSOR the Persians. According to Herodotus, Phei- του Μαραθώνα, εστάλη στη Σπάρτη να dippides arrived in Sparta the day after he ζητήσει βοήθεια στον πόλεμο εναντίον των Περσών. Σύμφωνα με τον Ηρόδοτο, left Athens. Based on his account, in 1982, ο Φειδιππίδης έφτασε στη Σπάρτη μια five officers and long distance runners of the μέρα μετά την αναχώρησή του από την British Air Force (RAF) traveled to Greece, Αθήνα. Βασισμένοι στις αναφορές του «Πριν φύγουν από την πόλη, οι στρατηγοί έστειλαν πρώτα μήνυμα led by Colonel John Foden. -

Spartathlon & the Legend of Pheidippides

Spartathlon & The Legend of Pheidippides Paul Ali & Paul Beechey The Legend of Pheidippides The legend of Pheidippides • In 490BC Athens needed the help of the Spartans against the invading Persians • Pheidippides, a professional runner was asked to run 150 miles to Sparta to ask for their help “AND FIRST, BEFORE THEY LEFT THE CITY, THE GENERALS SENT OFF TO SPARTA A HERALD, ONE PHEIDIPPIDES, WHO WAS BY BIRTH AN ATHENIAN, AND BY PROFESSION AND PRACTICE A TRAINED RUNNER...” (HERODOTUS) The legend of Pheidippides • Following a rugged difficult, mountainous route, Pheidippides delivered the message • However, the Spartan army could not take the field of battle until the Moon was full (due to religious laws) and would not reach the battle in time • Pheidippides then ran back to deliver the bad news. The legend of Pheidippides • Fortunately, the Athenians defeated the Persians in the “Battle of Marathon” • The surviving Persians headed towards Athens, to attack the city before the army could return • Pheidippides ran 25 miles to warn Athens “..WHO RAN IN FULL ARMOUR, HOT FROM THE BATTLE, AND, BURSTING IN AT THE DOORS OF THE FIRST MEN OF THE STATE, COULD ONLY SAy “HAIL! WE ARE VICTORIOUS” AND STRAIGHTAWAY he DIED. Interesting facts! • “Nike” is the Greek Goddess of victory and is where the the Sports clothes manufacturer got their name. • A “marathon” event gets it’s name from Pheidippides run from the Battle of Marathon to Athens. The history of spartathlon The HISTORY OF SPARTATLON • In 1982 British RAF Wing Commander John Foden and four other -

The Spartathlon 2011

The Spartathlon 2011 By Michael Arnstein The first time I heard the word ‘Spartathlon’ was from my longtime friend and training partner Oz Pearlman. Together, Oz and I have shared wild adventures and accomplished extreme challenges. We’ve both had our fair share of crazy ideas that we’ve dared on each other. Ultra running for many years has become the main challenge for both of us. We’ve progressed from running greater and greater distances each year, and now Spartathlon was our latest ultimate challenge. Spartathlon is a race held in Greece. The race probably has more historical meaning and history than any other sporting event in the history of mankind. Athens and Greece as a nation was the first modern society. The foundations of modern science, government, mathematics, astronomy, literature and more were all largely developed in ancient Greece. In 490 BC Ancient Athens was under siege. Democracy and the principles of how our modern society exists today were being threatened to extinction by ‘the barbarians’, armies from Persia that were ruled under Totalitarian oppression. The Generals of Athens desperately needed help from their neighboring state. They needed immediate reinforcements from the greatest warriors the world had ever known: The Spartan’s. Sparta is located in central Greece, in a dramatic valley surrounded by high mountains towering from all directions. Getting there from Athens quickly in 490BC was a monumental challenge, and hence the story of Pheidippides begins. Pheidippides was a messenger of the Athenian army. He had mythical endurance and speed to run huge distances in very short period of time. -

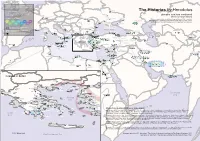

The Histories by Herodotus Chapter, a Hexagon with Light Border Is Drawn Near the Location the Character Hylaea Comes From

For each location mentioned in a chapter, a hexagon with dark border is drawn near that location. Dnieper For each character mentioned in a Gelonus The Histories by Herodotus chapter, a hexagon with light border is drawn near the location the character Hylaea comes from. placable locations mentioned Celts Danube Pyrene three or more times Chapter Color Scale: Gerrians Carpathian Mountains Tanaïs Where a region is dominated by a large settlement (like a capital), Far Scythia the settlement is generally used instead of the region to save space. I III V VII IX Some names in crowded locations on the map have been left out. Dacia Tyras Borysthenes II IV VI VIII Cremnoi Istros the place or the people was Illyria Scythian Neapolis mentioned explicitly Getae Marseille Odrysians Black Sea a character from nearby was Aléria Italy Mesambria Caucasus Massagetae Phasis mentioned Paeonia Sinop Pteria Caere Brygians Apollonia city or mountain location Mt. Haemus Caspian Byzantium Colchis Sea Sardinia Taranto Thyrea Sogdia Siris Velia Messapii Terme River Cyzicus Gordium Sybaris Crotone Cappadocia Sardis Armenia Messina Segesta Rhegium Greece Tigris Caspiane Tartessos Gela Pamphylia Parthia Carthage Selinunte Syracuse Milas Kaunos Cilicia Telmessos Nineveh Kamarina Lindos Posideion Xanthos Salamis Euphrates Kourion Ecbatana Amathus Gandhara Cyprus Tyre Sidon Cyrene Lotophagi Babylon Susa Barca Garamantes Macai Saïs Ienysos Heliopolis Petra Atlas Persepolis Asbystai Awjila Memphis Ammonians Egyptian Thebes Greece in detail Elephantine BC invasion b Myrkinos 480 y Xe rxes Red Macedonia Abdera Cicones Eïon Doriscus Sea Therma The Nile Olynthus Akanthos Thasos Cardia Sestos Pieria Vardar Samothrace Lampsacus Chalcidice Sane Imbros Abydos Pindus Mt.