The Regulation of Labor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridge of Spies

BRIDGE OF SPIES by Matt Charman and Ethan Coen & Joel Coen Final Shooting Script 12.17.14 12.17.14 FINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT 1. TITLE OVER BLACK: 1957. The height of the Cold War. The United States and the Soviet Union fear each other’s nuclear capabilities - and intentions. Both sides deploy spies - and hunt for them. INSPIRED BY TRUE EVENTS CLOSE ON AN ELDERLY MAN Reflected in a grimy mirror. The mirror is propped up on a chair next to an open window looking out from the fourth floor onto a Brooklyn skyline. Pull back to show the man sitting in a shabby workshop/studio. He looks from the mirror down at a canvas in front of him as he daubs paint onto a self-portrait. The telephone rings. The old man rests his brush on the easel and walks to a table cluttered with papers and shortwave radios. He picks up the phone and listens but doesn’t say anything. FULTON STREET The old man, Rudolf Abel, emerges from the building, walks along the street. TITLE: BROOKLYN An Agent follows Abel. SUBWAY TRAIN INTERIOR The Agent watches Abel as the train stops at Broad Street. The Agent, now joined by a second Agent, follows him at a distance. Abel dabs at his nose with a handkerchief. The agents lose him in the crush of commuters. They emerge from the station and consult two other Agents. No sign of Abel. First Agent heads back down the stair, smashing BANG right into Abel, who’s coming up the stairs. Abel looks up, surprised. -

Bridge of Spies by Giles Whittell Book

Bridge of Spies by Giles Whittell book Ebook Bridge of Spies currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Bridge of Spies please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 304 pages+++Publisher:::: Broadway Books (November 9, 2010)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0767931084+++ISBN- 13:::: 978-0767931083+++Product Dimensions::::5.2 x 0.7 x 8 inches++++++ ISBN10 0767931084 ISBN13 978-0767931 Download here >> Description: The dramatic events behind the Oscar-winning film, Bridge of Spies, tracing the paths leading to the first and most legendary prisoner exchange between East and West at Berlins Glienicke Bridge and Checkpoint Charlie on February 10, 1962.Bridge of Spies is the true story of three extraordinary characters whose fate helped to define the conflicts and lethal undercurrents of the most dangerous years of the Cold War: William Fisher, alias Rudolf Abel, a British born KGB agent arrested by the FBI in New York City and jailed as a Soviet superspy for trying to steal America’s most precious nuclear secrets; Gary Powers, the American U-2 pilot who was captured when his plane was shot down while flying a reconnaissance mission over the closed cities of central Russia; and Frederic Pryor, a young American graduate student in Berlin mistakenly identified as a spy, arrested and held without charge by the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police. The three men were rescued against daunting odds, and then all but forgotten. Yet they laid bare the pathological mistrust that fueled the arms race for the next 30 years.Weaving the three strands of this story together for the first time, Giles Whittell masterfully portrays the intense political tensions and nuclear brinkmanship that brought the United States and Soviet Union so close to a hot war in the early 1960s. -

Evaluating Bargaining Interest and Negotiation Style Using the Film Bridge of Spies

Journal of Business Cases and Applications Volume 20 Evaluating bargaining interest and negotiation style using the film Bridge of Spies Stuart H. Warnock Metropolitan State University of Denver Nancy J. Boykin Colorado State University ABSTRACT Bargaining and negotiation are topics frequently covered in a number of management and marketing courses and negotiation style and bargaining interest are topics commonly addressed. Since most students lack meaningful negotiation skills or experience, coverage of these topics is typically an abstract exercise. The academy award winning film Bridge of Spies (2015) provides an engaging way of covering these otherwise abstract concepts in an engaging and relatable way. This case provides historical background as well as background material on bargaining interest and negotiation style. It poses questions and identifies key segments of the film to help students explore these concepts in a meaningful and appealing way. Keywords: bargaining interest, negotiation style, bargaining style, negotiation, bargaining Copyright statement: Authors retain the copyright to the manuscripts published in AABRI journals. Please see the AABRI Copyright Policy at http://www.aabri.com/copyright.html Evaluating bargaining, Page 1 Journal of Business Cases and Applications Volume 20 NOTE TO INSTRUCTORS Students frequently have difficulty understanding the abstract nature of and subtleties associated with bargaining interest and different negotiation styles. At best, students may internalize definitions of these concepts, -

Bridge of Spies Free

FREE BRIDGE OF SPIES PDF Giles Whittell | 274 pages | 31 Jan 2012 | BROADWAY BOOKS | 9780767931083 | English | United States The True Story of 'Bridge of Spies' - Biography It stars Tom Hanks as attorney James Donovan, a man who first defended an accused Russian operative, then negotiated his swap for an American pilot held by the Soviet Union. InDonovan published a memoir about his unforgettable experiences called Strangers on a Bridge. Ina well-trained Soviet intelligence agent arrived in the United States. Using the alias Emil Goldfus, he set up an artist's studio in Brooklyn as a cover. Bridge of Spies his real name was William Fisher, he would become best known as Rudolf Abel. InAbel had the misfortune to be assigned an incompetent underling: Reino Hayhanen. After a few years of heavy drinking, and with no intelligence-gathering accomplishments, Hayhanen was told to return to the Soviet Union. Fearing the punishment that his shortcomings would bring, Hayhanen asked for asylum at the U. Embassy in Paris in May Abel had once made the mistake of bringing Hayhanen to his studio. After refusing to cooperate with the U. Now he needed a lawyer. Most importantly, he believed that everyone — even a suspected spy — deserved a vigorous defense, and accepted the assignment. Though Donovan and his family experienced some criticism, including angry letters and middle-of-the-night phone calls, his commitment to standing up for Abel's rights was largely respected. Donovan, supported by two other lawyers, scrambled to get ready for Abel's trial, which began in October Bridge of Spies Abel faced charges of 1 conspiracy to transmit military and nuclear information Bridge of Spies the Bridge of Spies Union; 2 conspiracy to gather this information; and 3 being in the United States without registering as a foreign agent. -

Attorney Ethics Questions in the Film “Bridge of Spies”

Attorney Ethics Questions in the Film “Bridge of Spies” Continuing Legal Education Presentation 1 CLE ethics credit will be applied for April 17, 2018 Madison Solo Roundtable The Film “Bridge of Spies” “Bridge of Spies” is a 2015 film set during the Cold War. In the movie, insurance lawyer James Donovan (Tom Hanks) defends Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance), who has been charged with espionage for the Soviet Union. Abel is convicted at trial. Although he avoids the death penalty, he is sentenced to a lengthy prison term. Soon thereafter, U.S. pilot Francis Gary Powers is shot down and captured while flying a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union. Powers is sentenced to prison in a show trial. Donovan is recruited by the CIA to go to Berlin to negotiate a prisoner exchange of Abel for Powers. While Donovan is in Berlin, the Berlin Wall is erected, and an American graduate student, Frederic Pryor, is imprisoned by the East Germans. Donovan successfully negotiates the exchange of Abel for both Powers and Pryor. The exchange of Abel for Powers takes place at the Glienicke Brücke in Berlin, popularly known as the “Bridge of Spies.” Meanwhile, Pryor is simultaneously released through “Checkpoint Charlie” at the Berlin Wall. In 2016, “Bridge of Spies” was nominated for six Academy Awards. The film won in one category: Best Supporting Actor for Mark Rylance, playing Rudolf Abel. James Donovan and “Bridge of Spies” in Real Life James Donovan graduated from Harvard Law School in 1940. During World War II, he served in the US Navy. -

Il Ponte Delle Spie

CINEMA Il ponte delle spie GIANCARLO ZAPPOLI lle 07.00 del 21 giugno 1957, l’Fbi venza civile. Anche ad Abel vanno garantiti arresta nel suo appartamento di i diritti che spettano a chiunque sia sotto - ABrooklyn Rudolf Abel, un agente posto a processo, indipendentemente da segreto dell’Unione Sovietica. Abel viene ciò che ha commesso e dalla sua cittadi - accusato di aver trasmesso alla Russia in - nanza. Donovan incontra Abel e ne pre - formazioni concernenti la difesa degli para la difesa apprezzandone la coerenza, Stati Uniti. Interrogato, rifiuta di rispon - la dignità e la lealtà verso il proprio Paese. dere e non accetta neanche la proposta di La sentenza appare però già scritta ancor rendere una piena confessione, accettare prima che si avvii il dibattimento, e la denaro e il ritiro delle accuse. Viene, sedia elettrica sembra ineluttabile. Ma quindi, chiuso in una prigione federale in Donovan non desiste e riesce, nonostante Steven Spielberg rievoca la vicenda che vide lo scambio tra l’agente sovietico Rudolf Abel attesa di essere processato. Il governo si gli ostacoli che gli vengono frapposti e le e il pilota americano Francis Gary Powers grazie alla mediazione dell’avvocato James Britt Donovan. trova nella necessità di assicurare la difesa non troppo velate minacce, a far derubri - La rilettura è finalizzata, più che a una ricostruzione dell’accaduto, alla descrizione del rapporto dell’imputato e ha bisogno di un legale in - care la condanna a morte in detenzione. tra Donovan e Abel e all’affermazione della necessità, in qualsiasi contingenza, del rispetto dei valori dipendente. -

All Faith Leaders Condemn Paris Carnage

Single Issue: $1.00 Publication Mail Agreement No. 40030139 CATHOLIC JOURNAL Vol. 93 No. 22 November 18, 2015 Residential Schools All faith leaders condemn Paris carnage The Catholic Church “diminishes itself every By Rosie Scannell day” by not telling the whole truth about the Indian VATICAN CITY (RNS) — Pope residential schools, says Francis raised the specter of a Third Stephen Kakfwi. “Things World War “in pieces,” Muslims issued statements of condemnation, will get better with or while evangelical Christians in without you, but I’d rather America debated whether to speak have you on our side.” of a “war with Islam.” — page 3 These were some of the re - sponses by religious leaders around CWL Clothing the world on Nov. 14 to the series Depot of attacks overnight in Paris, which left more than 120 people dead. Located in the heart of “This is not human,” Pope Saskatoon’s core neighbour - Francis said in a phone call to an hoods, the CWL Clothing Italian Catholic television station. Asked by the interviewer if it Depot provides clothing and was part of a “Third World War in household goods to those in pieces,” he responded: “This is a need, collecting donations piece. There is no justification for from the community and such things.” selling them at affordable Earlier, the Vatican’s chief prices. It is operated as a spokesperson, Rev. Federico joint project of Catholic Lombardi, released a statement Women’s League councils saying: “This is an attack on peace for all humanity, and it requires a in the Roman Catholic decisive, supportive response on Diocese of Saskatoon. -

Bridge-Of-Spies.Pdf

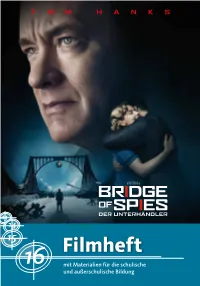

TOM HANKS EIN FILM 13 DER UNTERHÄNDLER 14 15 Filmheft 16 mit Materialien für die schulische und außerschulische Bildung Inhalt Credits / Hinweise auf Themen und Schulfächer .............................................................. 2 Einleitung .......................................................................................................................................3 Filminhalt ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Der Regisseur / Filmfiguren und reale Personen ...........................................................5/6 Arbeitsblatt 1: Im Netz der Spione? – Filmfiguren und ihre Bedeutung ..................................................7 Hinweise zum historischen Hintergrund (Kalter Krieg / Aufgabe und Bedeutung der Justiz) ......................................................... 8 Arbeitsblatt 2: Zum historischen Hintergrund von BRIDGE OF SPIES – DER UNTERHÄNDLER ....................................................................9/10 Spionage und „Informationskrieg“ (Spionage damals und heute) ..............................11 Arbeitsblatt 3: Spionage und Informationskrieg – Faszination und Gefahr ..........................................12 Besonderheiten der filmischen Inszenierung (Realität und Fiktion / Atmosphäre im Film) ................................................................13/14 Arbeitsblatt 4: Eine Zeitreise – Besonderheiten der filmischen Inszenierung .................................... 15 Filmbeobachtungsbogen -

BRIDGE of SPIES

JAMES DONOVAN GOES to BERLIN 0. JAMES DONOVAN GOES to BERLIN - Story Preface 1. RUDOLF ABEL - A SPY BORN in ENGLAND 2. RUDOLF ABEL MOVES to AMERICA 3. RUDOLF ABEL and HIS AMERICAN LIFE 4. RUDOLF ABEL at RISK 5. ARREST of RUDOLF ABEL 6. JAMES DONOVAN and RUDOLF ABEL 7. TRIAL of RUDOLF ABEL 8. FRANCIS GARY POWERS and the U-2 INCIDENT 9. TRIAL of FRANCIS GARY POWERS 10. JAMES DONOVAN and the MYSTERIOUS LETTERS 11. ABEL and POWERS - A SPY for a SPY 12. JAMES DONOVAN GOES to BERLIN 13. JAMES DONOVAN and WOLFGANG VOGEL 14. GLIENICKE - BRIDGE of SPIES 15. DONOVAN, ABEL and POWERS after the BRIDGE OF SPIES When James Donovan went to Berlin, to negotiate an exchange of Rudolf Abel for Francis Gary Powers, he entered a city divided by a wall. This image depicts construction of the Berlin Wall during August of 1961, about six months before Donovan arrived in Berlin. Image by Corey Hatch, University of Utah. Fair use for educational purposes. With the federal government’s approval, Jim Donovan sent a letter to “Frau Abel,” agreeing to meet with her in East Berlin. Already a walled-in city, East Berlin - to some people - seemed like an ominous place. Once inside the wall, was a person free to leave? Donovan agreed to meet with Frau Abel, at the Soviet Embassy, at noon on February 3, 1962. There were two other Americans being held by the Soviet Bloc - one in East Germany (a Yale student, from Michigan, named Frederic L. Pryor) and another in Kiev (a University of Pennsylvania student, Marvin Makinen) - who could be part of an exchange. -

Library Connection

Library Connection Volume 4, Issue 5, April 2017 Every year on the first day of spring, people in Poland gather to burn an effigy and throw it in the river to bid winter farewell. Libraries & Ideas This article was written by Library Director Drew Brookhart, and was published in the March 25th edition of the Columbus Telegram. The value of library service is often difficult to measure. Do we look at the number of books that are checked out? The people that come through the door? How do we compare these measures of use with the resources the community contributes for services? During the great recession, libraries, along with nearly everything else, were faced with budget constraints. Some overextended communities were even forced to foreclose on their libraries by either passing their operations to for-profit companies or simply closing the doors. These few tragedies aside most libraries were left articulating their worth in various ways. San Francisco undertook a study in September 2015 which projected an overall return on investment of between $5.19 and $9.11 for every dollar spent. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh estimated that they have generated $6.14 per $1 of budget provided; Florida public libraries showed that approximately $6.40 of the total value per $1 of the budget was created; South Carolina State Library’s economic impact was $4.48 per $1 spent; and Phoenix Public Library results showed a value of $10 or greater per $1 spent. In these examples the average return on investment is always higher than the www.columbusne.us/library 402-564-7116 resources expended. -

Bridge of Spies

1 Bridge of Spies Reviewed by Garry Victor Hill Produced by Stephen Spielberg, Kristie Macosko Krieger and Marc Platt. Directed by Stephen Spielberg. Screenplay by Joel & Ethan Cohen & Matt Charman. Production Design by Adam Stockhausen. Cinematography by Janusz Kaminski. Art Direction by Marco Bittner Rosser. Original Music by Thomas Newman. Edited by Michael Kahn. Cinematic length: 141 minutes. Distributed by 20th Century Fox and Walt Disney Pictures. Production Companies: Touchstone Pictures/Dreamworks Pictures/Fox 200 Pictures and several others. Cinematic release October 2015: Check for ratings. Rating 85 %. All images are from the public domain and Wikimedia Cast Tom Hanks as James B. Donovan Mark Rylance as Colonel Rudolf Abel Amy Ryan as Mary McKenna Donovan 2 Sebastian Koch as Wolfgang Vogel Alan Alda as Watters Austin Stowell as Francis Gary Powers Billy Magnussen as Doug Forrester Scott Shepherd as Hoffman Eve Hewson as Carol Donovan Jesse Plemons as Murphy Michael Gaston as Williams Peter McRobbie as Allen Dulles Domenick Lombardozzi as Agent Blasco Will Rogers as Frederic Pryor Dakin Matthews as Judge Mortimer W. Byers Stephen Kunken as William Tompkins Edward James Hyland as Chief Justice Earl Warren Francis Gary Powers Junior (uncredited) Review Bridge of Spies works well as a retelling of three Cold War incidents: the American capture of the Soviet agent Colonel Rudolph Abel in New York in 1957, the Soviet downing and capture of pilot Gary Powers in 1960 and the detention of an American student, Frederick Prior in East Berlin soon after. The four incidents eventually interweave. In the film they develop in the order just given - as they did in history. -

One Hundred Years of Economics at Swarthmore Joshua Hausman1

One Hundred Years of Economics at Swarthmore Joshua Hausman1 Swarthmore class of 2005 This paper presents a history of the Department of Economics at Swarthmore College from the founding of the college until 1970. Two themes dominate this narrative. First, the history of economics teaching at Swarthmore is one of nearly continuous growth and professionalization. When political economy was first offered at Swarthmore in 1872, there was only a single year-long course in the subject. It was taught by Maria Sanford, whose post- secondary education was at a Normal School, and who doubled as the sole professor of history at Swarthmore.2 In 1972, in contrast, the Swarthmore Economics Department offered twelve semester-long economics courses and eight seminars. It had eleven full and part-time members, seven of whom had economics Ph.Ds. And members of the Department were specialized teachers, usually teaching only a couple subject areas within economics. Despite this dramatic growth, there is a notable continuity in the history of economics at Swarthmore: a devotion to Quaker causes and social justice that often superseded purely theoretical interests. Maria Sanford, for example, would become famous for her commitment to progressive causes; after leaving Swarthmore, she gave public lectures that promoted the University of Minnesota. In the 1930’s, Patrick Malin, a member of the Department from 1930 to 1950 and a devout Quaker, worked unsuccessfully to make Swarthmore admit African-American students. Malin left Swarthmore in 1950 to lead the American Civil Liberties Union. Sanford and 1 Research assistant in the Division of International Finance of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.