Trust in the System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13273 PSA Conf Programme 2011 PRINT

Transforming Politics: New Synergies 61st Annual International Conference 18 – 21 April 2011 Novotel London West, London, UK PSA 61st Annual International Conference London, 18 –21 April 2011 www.psa.ac.uk/2011 A Word of Welcome Dear Conference delegate You are extremely welcome to this 61st Conference of the Political Studies Association, held in the UK capital. The recently refurbished Hammersmith Novotel hotel offers high quality conference facilities all under one roof. We are expecting well over 500 delegates, representing over 50 different countries. There are more than 190 panels, as well as the workshops on Monday, building on last year’s innovation, and as a new addition, dedicated posters sessions. There are also three receptions. The Conference theme is ‘Transforming Politics: New Synergies’. Keynote speakers include Professor Carole Pateman, President of APSA, revisiting the concept of participatory democracy and Professor Iain McLean giving the Government and Opposition-sponsored Leonard Schapiro lecture on the subject of coalition and minority government. On Wednesday, our after-dinner speaker is Professor Tony Wright, (UCL and Birkbeck College) former MP and Chair of the Public Administration Select Committee. Amongst other highlights, Professor Vicente Palermo will discuss Anglo-Argentine relations and John Denham MP will talk on ‘English questions’ and the Labour Party’ and Sir Michael Aaronson, former Director General of Save the Children, will be drawing on his experience working in crisis situations to reflect on whether we had a choice in Libya today. Despite the worsening economic and policy environment, this has been a particularly active and successful year for the Association. Overall membership figures, including those for the new Teachers’ Section, continue to rise. -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event. -

The Conservative Party & Perceptions of the Middle

THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY & PERCEPTIONS OF THE MIDDLE CLASSES TITLE: THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY AND PERCEPTIONS OF THE BRITISH MIDDLE CLASSES, 1951 - 1974 By LEANNA FONG, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Leanna Fong, August 2016 Ph.D. Thesis – Leanna Fong McMaster University - Department of History Descriptive Note McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2016) Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: The Conservative Party and Perceptions of the British Middle Classes, 1951 - 1974 AUTHOR: Leanna Fong, B.A., M.A (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Stephen Heathorn PAGES: vi, 307 ii Ph.D. Thesis – Leanna Fong McMaster University - Department of History Abstract “The Conservative Party and Perceptions of the British Middle Classes, 1951 – 1974,” explores conceptions of middle-class voters at various levels of the party organization after the Second World War. Since Benjamin Disraeli, Conservatives have endeavoured to represent national rather than sectional interests and appeal widely to a growing electorate. Yet, the middle classes and their interests have also enjoyed a special position in the Conservative political imagination often because the group insists they receive special consideration. It proved especially difficult to juggle these priorities after 1951 when Conservatives encountered two colliding challenges: the middle classes growing at a rapid rate, failing to form a unified outlook or identity, and the limited appeal of consumer rhetoric and interests owing to the uneven experience of affluence and prosperity. Conservative ideas and policies failed to acknowledge and resonate with the changing nature of their core supporters and antiquated local party organization reinforced feelings of alienation from and mistrust of new members of the middle classes as well as affluent workers. -

Literaturliste

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Sommersemester 2007 Institut für Politische Wissenschaft und Soziologie Hauptseminar für den Magister-Studiengang: Tony Blair und New Labour. Was bleibt? Dr. Brigitte Seebacher Literaturliste Signatur Titel A 06-07035 Astle, Julian (Ed.): Britain after Blair : a Liberal agenda. London 2006 POL 500 GROS Beck Becker, Bernd: Politik in Großbritannien. Paderborn 2002 X 08480/2001, 5 Suppl. Bischoff, Joachim / Lieber, Christoph: Epochenbegriff. „Soziale Gerechtigkeit“. Hamburg 2001 A 98-00618 Blair, Tony: Meine Vision. London 1997 A 05-04584 Coates, David: Prolonged labour : the slow birth of New Labour in Britain. Basingstoke 2005 A 06-03088 Coughlin, Con: American Ally. Tony Blair and the War on Terror. London 2006 A 00-04093 Dixon, Keith: Ein würdiger Erbe. Anthony Blair und der Thatcherismus. Konstanz 2000 C 06-00792 Haworth, Alan / Hayter, Dianne: Men Who Made Labour. 2006 A 06-07010 Hennessy, Peter: The prime minister. The office and its holders since 1945. London 2001 POL 500 GROS Hüb Hübner, Emil: Das politische System Großbritannien. Eine Einführung. 1999 [im Bestand nur die Auflage von 1998] A 06-07017 Jenkins, Simon: Thatcher & Sons: A Revolution in Three Acts. London 2006 A 06-00968 Kandel, Johannes: Der Nordirland Konflikt. Bonn 2005 POL 900 GROS Kaste Kastendiek, H / Sturm, R: (Hrsg): Länderbericht Großbritannien, Bonn 2006 (3. Aktualisierte und neu bearbeitete Auflage der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. POL 500 GROS Krumm Krumm, Thomas/ Noetzel, Thomas: Das Regierungssystem Großbritanniens. Eine Einführung. München 2006. POL 500 GROS Leach Leach, Robert/ u.a.: British politics. Basingstoke 2006 A 05-04568 Leonard, Dick: A century of premiers. Salisbury to Blair. -

Progressive Politics

the Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson The Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson The Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson Department of Politics University of Sussex Brighton, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-137-50661-0 ISBN 978-1-137-50664-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-50664-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016963256 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

X Marks the Box: How to Make Politics Work for You by Daniel Blythe

Thank you for downloading the free ebook edition of X Marks the Box: How to Make Politics Work for You by Daniel Blythe. This edition is complete and unabridged. Please feel free to pass it on to anyone else you think would be interested. Follow Daniel on his blog at www.xmarksthebox.co.uk. The book is all about debate, of course – so get involved and tell Daniel and the world what you think there! The printed edition of X Marks the Box (ISBN 9781848310513), priced £7.99, is published on Thursday 4 March by Icon Books and will be available in all good bookstores – online and otherwise. And don’t forget to vote! www.xmarksthebox.co.uk I C O N B O O K S Published in the UK in 2010 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected] www.iconbooks.co.uk This electronic edition published in 2010 by Icon Books ISBN: 978-1-84831-180-0 (ePub format) ISBN: 978-1-84831-191-6 (Adobe ebook format) Printed edition (ISBN: 978-1-84831-051-3) sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents Printed edition distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road, Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW Printed edition published in Australia in 2010 by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065 Printed edition distributed in Canada by Penguin Books Canada, 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE Text copyright © 2010 Daniel Blythe The author has asserted his moral rights. -

Wales: the Heart of the Debate?

www.iwa.org.uk | Winter 2014/15 | No. 53 | £4.95 Wales: The heart of the debate? In the rush to appease Scottish and English public opinion will Wales’ voice be heard? + Gwyneth Lewis | Dai Smith | Helen Molyneux | Mark Drakeford | Rachel Trezise | Calvin Jones | Roger Scully | Gillian Clarke | Dylan Moore | The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • Acuity Legal • Age Cymru • BBC Cymru Wales • Arriva Trains Wales • Alcohol Concern Cymru • Cardiff County Council • Association of Chartered • Cartrefi Cymru • Cardiff School of Management Certified Accountants (ACCA) • Cartrefi Cymunedol • Cardiff University Library • Beaufort Research Ltd Community Housing Cymru • Centre for Regeneration • Blake Morgan • Citizens Advice Cymru Excellence Wales (CREW) • BT • Community - the union for life • Estyn • Cadarn Consulting Ltd • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Glandwr Cymru - The Canal & • Constructing Excellence in Wales • Disability Wales River Trust in Wales • Deryn • Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru • Harvard College Library • Elan Valley Trust • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Heritage Lottery Fund • Eversheds LLP • Friends of the Earth Cymru • Higher Education Wales • FBA • Gofal • Law Commission for England and Wales • Grayling • Institute Of Chartered Accountants • Literature Wales • Historix (R) Editions In England -

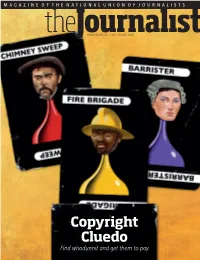

Copyright Cluedo Find Whodunnit and Get Them to Pay Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | JULY-AUGUST 2018 Copyright Cluedo Find whodunnit and get them to pay Contents Main feature 12 Close in and win The quest for copyright justice News opyright has been under sustained 03 STV cuts jobs and closes channel attack in the digital age, whether it is through flagrant breaches by people Pledge for no compulsory redundancies hoping they can use photos and 04 Call for more disabled people on TV content without paying or genuine NUJ backs campaign at TUC conference Cignorance by some who believe that if something is downloadable then it’s free. Photographers 05 Legal action to demand Leveson Two and the NUJ spend a lot of time and energy chasing copyright. Victims get court go-ahead This edition’s cover feature by Mick Sinclair looks at a range of 07 Al Jazeera staff win big pay rise practical, good-spirited ways of making sure you’re paid what Deal reached after Acas talks you’re owed. It can take a bit of detective work. Data in all its forms is another big theme of this edition. “Whether it’s working within the confines of the new general Features data protection regulations or finding the best way to 10 Business as usual? communicate securely with sources, data is an increasingly What new data rules mean for the media important part of our work. Ruth Addicott looks at the implications of the new data laws for journalists and Simon 13 Safe & secure Creasey considers the best forms of keeping communication How to communicate confidentially with sources private. -

Politics, Policy and the Internet:Charity 5/2/08 15:39 Page 1

Politics, policy and the internet:Charity 5/2/08 15:39 Page 1 CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES “In January 2007, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama launched their bids for the most powerful position in the world. But there was no bunting or cheering crowds. Instead, both candidates for the US Presidency made their announcements in a manner inconceivable just a few years ago: they released videos on their websites.” Politics, Policy and Television and radio transformed the way politics operated in the twentieth century. And, predicts the Internet Robert Colvile, the internet could do the same in the twenty-first. Yet the main British political parties are failing to exploit its potential. The BNP website has the ROBERT COLVILE same market share as all of the other major political parties combined. The internet will bring a far greater openness to politics, helping the activist and the citizen hold politicians to account. The web could also re-empower MPs, by linking them far more directly to the concerns of their constituents. And for policy development, the internet will revolutionise the way policy-making works. The most subtle, but perhaps most powerful, change, may be to the public’s mindset. As we grow used to the instant availability of information online, we will no longer tolerate delay and obfuscation in getting similar information from government. The individual, and not the state, will be the master in the digital age. Price: £5.00 Politics, Policy and the Internet ROBERT COLVILE CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QL 2008 THE AUTHOR ROBERT COLVILE is a features editor and leader writer at The Daily Telegraph, where he also writes extensively about technology. -

Champion of Liberalism Helen Langley Honor Balfour and the Liberal Party an Archival Perspective Will Pinkney C

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 78 / Spring 2013 / £6.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Champion of Liberalism Helen Langley Honor Balfour and the Liberal Party An archival perspective Will Pinkney C. E. Montague, Liberal war writers and the Great War Peter Urbach The Reform Club’s Jubilee Ball End of an era Tudor Jones ‘Reluctant’ or Liberal collectivists? The Social Liberalism of Keynes and Beveridge Ruth Polling Mothers of Liberty How modern Liberalism was made by women Liberal Democrat History Group 2 Journal of Liberal History 78 Spring 2013 Journal of Liberal History Issue 78: Spring 2013 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack History Group plaque; PhD in political history; Archiving the ‘Red Guard’; The Deputy Editor: Tom Kiehl Liberal Party, Unionism and political culture Assistant Editor: Christine Headley Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini Honor Balfour and the Liberal Party 6 Contributing Editors: Graham Lippiatt, Tony Little, An archival perspective; by Helen Langley York Membery C. E. Montague, Liberal war writers and the Great 20 Patrons Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; War Professor John Vincent Will Pinkney examines the war writings of a Liberal author Editorial Board Letters to the Editor 25 Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Ian Cawood; Dr Roy Douglas; D. S. Macdonald (David Steel); Immigration (Sandy S. Waugh); Roy Jenkins and Dr David Dutton; Prof. David Gowland; Prof. Richard Lloyd George (Alan Mumford); C. L. Mowat and Lloyd George (Rufus Adams) Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Dr Alison Holmes; Dr J. -

Iain Dale: All Talk Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2019

James Seabright in association with Northbank Speakers presents Iain Dale: All Talk Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2019 **12 extra shows added due to popular demand** **19 new star guests** Yasmin Alibhai-Brown and Kate Adie; Christopher Biggins; Professor John Curtice and Michael Crick; Anne Diamond and Nick Owen; Matt Forde, Andrew Doyle and Grace Campbell; Paul Gambaccini; Neil Hamilton and Christine Hamilton; Brandon Lewis MP and Eric Pickles; Len McCluskey; Sir Nicholas Soames; Dr David Starkey; Jo Swinson MP. Gilded Balloon at the Museum (Venue 64) 31 July - 11 August, 6.00pm (60 mins) ‘Iain Dale is that rare beast – a forensic and mischievous interviewer with a deep sense of humanity and kindness beneath the brilliant probing.’ Emily Maitlis, BBC Newsnight Following the huge interest in the original line-up of ‘All Talk’ (which includes Nicola Sturgeon MSP, John McDonnell MP and CNN host Christiane Amanpour), award-winning LBC radio presenter, CNN political commentator and ‘For the Many’ podcast co-host, Iain Dale brings more stellar guests to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Between 31 July and 11 August, Iain will add to his original afternoon slot with a 6pm show that includes: Conservative Party Chairman, Brandon Lewis MP and former Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Eric Pickles; General secretary of Unite the Union, Len McCluskey; at the time of writing, Lib Dem leader-in-waiting, Jo Swinson MP; UKIP Wales leader and Mid & West Wales AM Neil Hamilton and self- confessed ‘battleaxe’ Christine Hamilton; renowned -

Hoddercat Autumn20 Reduced.Pdf

3 49 53 71 83 sales information 95 N @hodderbooks M HodderBooks [ @hodderbooks July 2020 Satire . Humorous Fantasy . Absurdist THE CONSTANT RABBIT Jasper Fforde It’ll take a rabbit to teach a human humanity. England, 2020. There are 1.2 million human-sized rabbits living in the UK. They can walk, talk and drive cars, the result of an Inexplicable Anthropomorphising Event 55 years ago. When a family of rabbits move into the village of Much Hemlock, no sooner have they arrived than the villagers decide they must depart. Except their neighbours, long-time residents Peter Knox and his daughter Pippa. With the full power of the ruling United Kingdom Anti Rabbit Party against them, Peter and Pippa soon fi nd that you can be a friend to rabbits or humans, but not both . Jasper Fforde spent 20 years in the fi lm business before debuting on the New York Times bestseller list with The Eyre Affair in 2001. Since then he has written another 12 novels, including the Number One Sunday Times bestseller One of Our Thursdays is Missing, The Last Dragonslayer series, adapted for television by Sky, and most recently Early Riser. Fforde lives and works in his adopted nation of Wales. 9781444763621 • £18.99 Most recent title: EARLY RISER Publicity contact: Steven Cooper Royal Hardback • 320pp Advance book proofs available on request Exclusive territories: eBook: 9781444763652 • £18.99 BCN ex Can, inc EU Author lives in Hay-on-Wye, Wales. Audio download: US Rights: Viking Author is available for: events 9781444763713 • £20.00 Translation Rights: Janklow & Nesbit and signings to be confi rmed.