Vol 3, 3, Cover Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

The Enigma of the Mason Hymn-Tunes

Title: The Enigma of the Mason Hymn-Tunes Author(s): George Brandon Source: Brandon, G. (1992, Fall). The enigma of the Mason hymn- tunes. The Quarterly, 3(3), pp. 48-53. (Reprinted with permission in Visions of Research in Music Education, 16(3), Autumn, 2010). Retrieved from http://www-usr.rider.edu/~vrme/ It is with pleasure that we inaugurate the reprint of the entire seven volumes of The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning. The journal began in 1990 as The Quarterly. In 1992, with volume 3, the name changed to The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning and continued until 1997. The journal contained articles on issues that were timely when they appeared and are now important for their historical relevance. For many authors, it was their first major publication. Visions of Research in Music Education will publish facsimiles of each issue as it originally appeared. Each article will be a separate pdf file. Jason D. Vodicka has accepted my invitation to serve as guest editor for the reprint project and will compose a new editorial to introduce each volume. Chad Keilman is the production manager. I express deepest thanks to Richard Colwell for granting VRME permission to re-publish The Quarterly in online format. He has graciously prepared an introduction to the reprint series. The Enigma Of The Mason HYfl1fl-Tunes By George Brandon Davis, California orn into a familv of active amateur Many younger men of Mason's time, in- musicians, Lowell Mason attended cludingJ. S. Dwight and A. W. Thayer, prob- Bsinging schools conducted by local ably looked upon Lowell Mason as an elder figures such as Amos Albee and Oliver Shaw. -

Appendix to the Elements of Vocal Music, Containing Exercises for Practice

PUBLIC LIBRARY OF CINCINNATI AND HAMILTON COUNTY Aulhoriied in 1853 as a Public and School Library, it became in 1867 an independent Public Library for the city, and in 1898 the Library for all of Hamilton County. Departmenu in the central building,branch librariea, lUtiont and bookmobile* provide a lending and reference lervice of literary, educational and recreational nulenal for aU. TTu Futlit Library u Yours . Vu it! Form No. 00101 RECOMMENDATIONS. lfIA80]\lS' 8ACRED HARP, or Beauties ot Church IVIuisic, is adapted to the wants of all denominations. The variety of metres is very great, and but few Hymns are contained in the Hymn Books of the different christian worshippers, for which a tune may not be found in this collection; It will be found to contain a great variety of Psalm and Hymn tunes; also a collection of interesting Anthems, Set Pieces, Sacred Songs, Sentences and Chants, which are short, easy of performance without instrumental aid, and appropriate to the various occasions of public worship, the wanta of singing schools, musical societies, and pleasing and useful to singers for their own private practice and improvement. MASONS' various collections have all been preeminently popular and useful in the estimation of men of science and taste, both in Europe and America. The Sacred Harp is the authors' last production, and it is not excelled by any other collection. Teachers of singing, clergymen and others who are desirous of promoting Sacred Music, can employ no means so effectual as the circulation of this valuable work. From the JVew York Evangelist: edited by J, Leavitt, author of the Christian Li/re, a From Mr. -

Reshaping American Music: the Quotation of Shape-Note Hymns by Twentieth-Century Composers

RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS by Joanna Ruth Smolko B.A. Music, Covenant College, 2000 M.M. Music Theory & Composition, University of Georgia, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Faculty of Arts and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Historical Musicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Joanna Ruth Smolko It was defended on March 27, 2009 and approved by James P. Cassaro, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music Mary S. Lewis, Professor, Department of Music Alan Shockley, Assistant Professor, Cole Conservatory of Music Philip E. Smith, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Deane L. Root, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Joanna Ruth Smolko 2009 iii RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS Joanna Ruth Smolko, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Throughout the twentieth century, American composers have quoted nineteenth-century shape- note hymns in their concert works, including instrumental and vocal works and film scores. When referenced in other works the hymns become lenses into the shifting web of American musical and national identity. This study reveals these complex interactions using cultural and musical analyses of six compositions from the 1930s to the present as case studies. The works presented are Virgil Thomson’s film score to The River (1937), Aaron Copland’s arrangement of “Zion’s Walls” (1952), Samuel Jones’s symphonic poem Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1974), Alice Parker’s opera Singers Glen (1978), William Duckworth’s choral work Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1980-81), and the score compiled by T Bone Burnett for the film Cold Mountain (2003). -

The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827 Todd R. Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9464-8358 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.133 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Todd R., "The Relationship Between Lowell Mason and the Boston Handel and Haydn Society, 1815-1827" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 83. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/83 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Musical Gazette (New York, 1854-1855)

Introduction to: Randi Trzesinski and Richard Kitson, The Musical Gazette (1854-1855) Copyright © 2007 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) The Musical Gazette (1854-1855) The Musical Gazette [MGA] was published weekly on Saturdays in New York City by the Mason Brothers from 11 November 1854 until 5 May 1855, and comprised twenty-six weekly numbers, the first two containing sixteen pages each, the remainder eight pages each. The issues are numbered from 1 through 26 and the pages are numbered consecutively from 1 through 208. In 1851 Daniel Gregory Mason (1820-1869) and his brother Lowell Mason (1823-1885)—sons of music educator and composer Lowell Mason—united with Henry W. Law to create the Mason & Law publishing firm. Daniel Gregory and Lowell Mason, Junior established in 1853 their own firm, the Mason Brothers, publishers of secular and religious music, school textbooks, histories, English and French dictionaries and music periodicals.1 In 1854 they undertook publication of The Choral Advocate and Singing-Class Journal, and began two new musical periodicals in November of that year, The Musical Gazette (edited by Lowell Mason, Junior) and The Musical Review. After 5 May 1855 MGA was absorbed into another music journal published by the Mason Brothers, The New-York Musical Review and Choral Advocate which was then renamed The New-York Musical Review and Gazette.2 The Mason Brothers’ principal goal for MGA was publication of a journal “devoted to the higher departments of musical literature and criticism; … Musical news from all parts of the world, where music is cultivated, will be promptly and regularly given.”3 Each page of MGA is printed in a two-column format and issues are organized in three main parts. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Americans at the Leipzig Conservatory (1843–1918) and Their Impact on AJoamnnae Perpipclean Musical Culture Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AMERICANS AT THE LEIPZIG CONSERVATORY (1843–1918) AND THEIR IMPACT ON AMERICAN MUSICAL CULTURE By JOANNA PEPPLE A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Copyright © 2019 Joanna Pepple Joanna Pepple defended this dissertation on December 14, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: S. Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation George Williamson University Representative Sarah Eyerly Committee Member Iain Quinn Committee Member Denise Von Glahn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii Soli Deo gloria iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so grateful for many professors, mentors, family, and friends who contributed to the success of this dissertation project. Their support had a direct role in motiving me to strive for my best and to finish well. I owe great thanks to the following teachers, scholars, librarians and archivists, family and friends. To my dissertation committee, who helped in shaping my thoughts and challenging me with thoughtful questions: Dr. Eyerly for her encouragement and attention to detail, Dr. Quinn for his insight and parallel research of English students at the Leipzig Conservatory, Dr. -

“Why Should the Devil Have All the Pretty Tunes?” the Great Awakening of a New American Idiom: Organ Music Based on Shape-Note Hymns

“WHY SHOULD THE DEVIL HAVE ALL THE PRETTY TUNES?” THE GREAT AWAKENING OF A NEW AMERICAN IDIOM: ORGAN MUSIC BASED ON SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS by SARAH ROBERTA READ-GEHRENBECK Submitted to the faculty of the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2017 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Christopher Young, Research Director & Chair ______________________________________ Janette Fishell ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart ______________________________________ Gretchen Horlacher ______________________________________ Marilyn Keiser December 6, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Sarah Roberta Read-Gehrenbeck iii Acknowledgements I wish to express my profound gratitude to my professors, who have been a great source of inspiration to me. Each one brought a unique palette of knowledge and experience to bear upon this project. Thank you, Dr. Young, for your guidance and insight as my Research Director. You have always given me a great deal to think about—the breadth and depth of your knowledge is truly stunning. A special thank you to Dr. Keiser – the reason I came to Indiana University in the first place. You planted and nourished the seeds of my passion for Hymnody, and you have supported my work from the beginning to the end of my studies. You have mentored me, and inspired me with your leadership and passion for education and per- formance. I count my blessings that I was able to absorb your wisdom as your Music Intern at Trinity. Prof. -

The Southern Harmony

The Southern Harmony Author(s): Walker, William (1809-1875) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Subjects: Music Vocal music Sacred vocal music Hymnals. Hymn collections i Contents Home 1 Original Title Page 2 About 3 Preface 4 Introduction by Harry Eskew 6 About the On-line Southern Harmony 11 The Gamut, or Rudiments of Music 12 Part I. Plain and Easy Tunes 13 Liverpool 14 Invitation 16 Primrose 18 Kedron 19 Meditation 20 Hanover 21 Supplication 23 Restoration 24 Marysville 25 King of Peace 26 Ninety-Third Psalm 27 Weeping Saviour 29 New Britain 30 Cookham 32 The Converted Thief 33 Webster 35 Ortonville 36 Jerusalem 38 ii Salem [1] 40 Dublin 42 Devotion 43 Minister's Farewell 44 Davis 46 Star in the East 48 Middlebury 50 Consolation 51 Complainer 53 Hicks' Farewell 55 Canon 57 The Family Bible 58 Old Hundred 60 Distress 61 Albion 62 Charlestown 63 Prospect of Heaven 64 Mear 65 Crucifixion 66 Indian's Farewell 67 The Christian 69 Carnsville 71 America 72 Ninety-Fifth 73 Tennessee 74 Solemn Thought 76 Separation 77 Idumea 78 Suffield 79 The Midnight Cry 80 Confidence 83 Vernon 85 iii Imandra New 87 Cross of Christ 88 Parting Friends 89 The Soldier's Return 90 The Christian Warfare 91 Resignation 93 Bozrah 95 Union 96 Detroit 97 Happiness 99 The Spiritual Sailor 100 Jefferson 102 The Turtle Dove 103 Morality 105 Christian Soldier [1] 107 Evening Shade 109 Judgment 111 Windham 112 Fairfield 113 The Good Physician 114 Captain Kidd 116 The Promised Land 118 Babel's Streams 119 Mutual Love 120 Salem [2] 121 Exhilaration -

Voices United Licensing Agency Index

Voices United Public Domain & © The United Church of Canada Hymn Title Acknowledgement 1 © copyright Licensing Agency 2 2 Come, Thou Long-Expected Words: Charles Wesley 1744. Music: Psalmodia Sacra 1715 Public Domain. N/A Jesus 3 Plus de nuit, le jour va naître Words: French para. H. Cousin. Public Domain. N/A 8 Lo, How a Rose E’er Words: German 15th century. English translation: Theodore Baker. Public Domain. N/A Blooming French translation: L. Monastier. Music: German traditional melody. Harmonized by Michael Praetorius. 25 Lo, He Comes with Clouds Words: John Cenwick. Revised by Charles Wesley and Martin Madan. Public Domain. N/A Descending Music: English melody. Arranged by Thomas Olivers. 30 Hail to God’s Own Anointed Words: James Montgomery. Music: Johann Cruger, adapted W.H. Public Domain. N/A Monk. 31 O Lord, How Shall I Meet Words: Paul Gerhardt. Translation: Catherine Winkworth, et al., alt. Public Domain. N/A You Music: Melchior Teschner, harmonized by William Henry Monk. 38 Angels We Have Heard on Words: French traditional, translation James Chadwick. Music: French Public Domain. N/A High carol melody, arranged by Edward Shippen Barnes. 44 It Came upon the Midnight Words: Edmund Hamilton Sears. Music: Richard Storrs Willis. Public Domain. N/A Clear 48 Hark! The Herald Angels Words: Charles Wesley. Music: Felix Mendelssoln, adaptation: Public Domain. N/A Sing William Hayman Cummings. 55 In the Bleak Midwinter Words: Christina Georgina Rossetti ca. 1872. Music: Gustav Theodor Public Domain. N/A Holst 1906. 59 Joy to the World Words: Isaac Watts 1719, alt. Music: attributed to George Frideric Public Domain. -

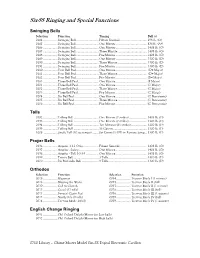

Six-SS Ringing and Special Functions

Six-SS Ringing and Special Functions Swinging Bells Selection Function Timing Bell (s) 0184 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ Fifteen Seconds.................................. 198 lb. (G) 0185 .................Swinging Bell ............................ One Minute....................................... 836 lb. (A#) 0186 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ One Minute....................................... 1408 lb. (G) 0187 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ Three Minute..................................... 1408 lb. (G) 0188 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ Five Minute ....................................... 1408 lb. (G) 0189 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ One Minute....................................... 3300 lb. (D) 0190 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ Three Minute..................................... 3300 lb. (D) 0191 ..................Swinging Bell ............................ Five Minute ....................................... 3300 lb. (D) 0180 ..................Four Bell Peal............................ One Minute....................................... (D# Major) 0181 ..................Four Bell Peal............................ Three Minute..................................... (D# Major) 0182 ..................Four Bell Peal............................ Five Minute ....................................... (D# Major) 0183 ..................Three Bell Peal......................... -

Elias Henry Johnson and Anglican Chant in Baptist Hymnals

‘More Than Half a Fool’: Elias Henry Johnson and Anglican Chant in Baptist Hymnals Lance Peeler “As I have told you, if there is anything new to be done it is in this style of music.” So said Elias Henry Johnson, referring to what he called the “English choral style,” demonstrating his love for and knowledge of Anglican music. Fashionable in Anglican music of the time was Anglican chant, a form of chant in four-part homophony. The basic form of Anglican chant is binary, with each section beginning with a reciting tone and concluding with a cadential formula. The text is pointed to link it to the musical formula.1 Many Baptist hymnals of the nineteenth century included chant, especially those edited by Johnson. The only scholarly coverage of Anglican chant in Baptist hymnals is Paul Richardson’s article, “Sweet Chants that Led My Steps Abroad.” Richardson asks several questions in his conclusion, among them—using Richardson’s numbering—(1) What led Baptists to publish chants? (2) What were the sources, direct and indirect, of the texts and tunes? (3) How were particular items transmitted, adapted, and revised? (8) To what extent did this practice extend into the twentieth century?2 This paper will address these questions by briefly discussing the first Baptist hymnal to include chants, examining a chant book that influenced Johnson’s work in editing hymnals with chants, and highlighting how long these chants were retained in Baptist hymnals. 1 Paul A. Richardson, “Sweet Chants That Led My Steps Abroad: Anglican Chant in Nineteenth-Century American Baptist Hymnals,” in We'll Shout and Sing Hosanna: Essays on Church Music in Honor of William J.