Undernutrition in the Philippines Scale, Scope, and Opportunities for Nutrition Policy and Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow the Money: the Philippines

A Rapid Assessment of Gold and Financial Flows linked to Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Philippines FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES October 2017 PB FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES i ii FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES iii A Rapid Assessment of Gold and Financial Flows linked to Artis- anal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Philippines FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES October 2017 ii FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES iii © UNIDO 2017. All rights reserved. This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” or “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. Unless otherwise mentioned, all references to sums of money are given in United States dollars. References to “tons” are to metric tons, unless otherwise stated. All photos © UNIDO unless otherwise stated iv FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES v Acknowledgments This report was authored by Marcena Hunter and Laura Adal of the Global Initiative against Transnational Orga- nized Crime. -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao Del Sur (Brackishwater Areas)

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) AMC MINI PROJECT: TEAM TILAPIA Acuna, Thaddeus R., UP Mindanao Almazan, Cynthia V., DOST-PCAARRD Castillo, Monica, DOST-PCAARRD Romo, Glory Dee A., UP Mindanao Rosetes, Mercy A., Foodlink Advocacy Co-operative (FAC) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) OBJECTIVE To conduct a market assessment of expanding areas for tilapia culture production in costal and brackishwater areas in the province of Davao del Sur. RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. Does consumption level of Tilapia a key contributing factor for potential expansion of Tilapia production in Davao del Sur? 2. Is the market potential of competitiveness of Tilapia substantial enough to revitalize tilapia production in Davao del Sur? RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) METHODOLOGY RAPID APPRAISAL APPROACH Secondary data Encoding Market Areas for gathering Constraints Intervention Primary data Market gathering Competitiveness * KIs Market * Market Mapping Opportunities * Market Visits A Step-by step approach of Rapid Market Appraisal (Adapted from the RMA proposal for underutilized fruits) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) INDUSTRY SITUATION ✓ Tilapia is a major aquaculture product in the Philippines that is considered important to the country’s food security and nutrition (Perez, 2017) ✓ Most -

CALIMAG INDUCTED ANEW in This Issue

JUNE 2015 AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PHILIPPINE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOLUME XXV NO. 1 CALIMAG INDUCTED ANEW In this issue: From the President's Desk p2-3 Editorial p4 As I See It p5 Dates to Remember p6 The Vice President's Corner p7 Maria Minerva P. Calimag, M.D. was emotionally; that they all love their fellow Money Matters: The inducted as 2015-2016 Philippine Medical physicians because that was what they have National Treasurer's Association President by Hon. Commissioner sworn to do when they took the Oath of Report p8-9 Florentino C. Doble, MD, PRC Chairman, during Hippocrates; that they should love the th Know your Governor the closing ceremonies of the 108 PMA Philippine Medical Association because it was p12-19 Annual Convention at the Marriott Grand built upon the age-old ideals of its founders as Ballroom in Pasay City. Dr. Calimag was an association of all physicians that would look Feature p20-21 reelected PMA President during the March 15, after each other‟s welfare. She urged the The MCP-KLP p22 2015 National Elections. members to thwart any attempt by any sector to disembowel the profession, to divide the MERS-CoV p23 In her speech, Dr. Calimag said that physicians, and disintegrate the PMA in the doctors have been under constant external exchange for personal gains or political CME Commission p24 threats but a united front and a solid ambitions. foundation would be their shield against all of Specialty & Affiliate these threats. She also stated that the Dr. Calimag asked all physician-leaders Societies p26-27 physicians are revered and looked up to by present during the closing ceremonies to society because eminence, empathy, erudition stand up, recite and live up to heart the and expertise have been the values attributed Declaration of Commitment to the Ethos of the to them. -

PHL-OCHA-R11 Profile-A3

Philippines: Region XI (Davao) Profile Region XI (Davao) is located in the southeastern POPULATION POVERTY portion of the island of Mindanao surrounding the Davao Gulf. Source: PSA 2010 Census Source: PSA 2016 It is bordered to the north by the provinces of Surigao del Sur, 5 6 43 1,162 Region XI population Region XI households 2.39M Poverty incidence among population (%) Agusan del Sur, and Bukidnon, on the east by the Philippine PROVINCES CITIES MUNICIPALITIES BARANGAYS Sea, and on the west by the Central Mindanao provinces. 4.89 1.18 48.9% 60% million million 40% 30.7% Female 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 30.6% 31.4% + 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 9 4 - Population statistics trend - - - - - - - - - - 20% - - 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 6 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 22.0% Male 0 2006 2009 2012 2015 51.1% 4.89M 4.47M 2015 Census 2010 Census 2.50M % Poverty incidence 0 - 14 15 - 26 27 - 39 40 - 56 57 - 84 DAVAO DEL NORTE NATURAL DISASTERS HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Nabunturan 4,300 Source: OCD/NDRRMC Conditional cash transfer Source: DSWD 117 Number of disaster beneficiaries (children) incidents per year 562,200 272,024 Tagum Affected population 451,700 31 (in thousands) 21 21 24 427,500 219,637 Notable incidents Typhoon 209,688 COMPOSTELA 300,500 Girls Flooding 290,158 232,085 119,200 VALLEY 147,666 248 No affected population 217,764 107,200 2 94 27 due to tropical cyclones in 2015 and 2016 DAVAO ORIENTAL 152,871 Boys Davao City 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 Mati DAVAO DEL SUR NUTRITION WATER AND SANITATION HEALTH Source: FNRI 2012 Source: PSA 2010 -

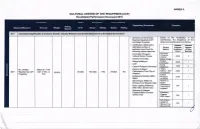

(CCP) Revalidated Performance Scorecard 201 6

ANNEX A GULTURAL CENTER OF THE PHTLTPPTNES (CCP) Revalidated Performance Scorecard 201 6 Component Target Submission GCG Validation Supporting Documents Remarks Rating Objective/Measure Formula Weight 2016 Rating System Actual Rating Actual so1 Contributed Significantly to lnclusive Growth, lndustry Relevant and Socially Responsive to the Global Environment o Summary of 2016 Areas Based on the revalidation of the Reached Quarterly CCP submissions, the breakdown of the Exchange Programs actual accomplishment is as follows: o Certification attesting the Attested Attested estimated number of Partner Estimate Number audience count from the Agency Audience of Sites following partner agencies: Count Reached Koronadal Hinugyaw Koronadal - Hinugyaw 4,500 2 Cultural Dance Troupe, Cultural - Kanami Koronadal, Bulakenyo, - Sining 9,000 1 Koronadal E, - CCP, lu o - Central Philippine University 7,000 2 oJ I - Harana sa Bayan Teatro uJ No. of Sites Below 21 = 0o/o Y '143 Performance Tour (City of Obrero/ CCP 4,500 1 SM1 Reached by CCP (>21x1Oo/o)x 10.00% 30 sites sites 10o/o 24 sites 8o/o oF Programs 100 Angeles) - Kabataang Gitarista (MSU- Philippine 3,100 ,| lligan) - Gift of Music NAMCYA SA Winners Tour (Bacolod City) Bayan Performance Basic Lighting Workshop 350 1 - Tour (City of (MSU-Gen. Santos City) Angeles) - Opening of Kalingan Fesetival (MSU-General Santos City) Gitarista 260 1 (MSU-lligan) NAMCYA 300 1 Winners Tour Bacolod \ cULTURAL CENTER OF THE PHTLTPPTNES (CCP) Validated Performance Scorecard 2016 Basic Lighting Workshop 28 Kalingan 1 Fesetival (MSU- 7000 General o Summary of 2016 Tanghalang 570 3 Accomplishments (Cultural Pilipino Exchange Department) . National Park & . Certification attesting the Developmen estimated number of t Commiftee audience count from the o Philippine following partner agencies: Coast Guard - Koronadal Hinugyaw . -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY NIA Northside Road, National Government Center Barangay Pinyahan, Quezon City

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY NIA Northside Road, National Government Center Barangay Pinyahan, Quezon City PRESS RELEASE# 388/16 DATE : August 24, 2016 AUTHORITY : ISIDRO S LAPEÑA, PhD, CSEE Director General For more information, comments and suggestions please call: DERRICK ARNOLD C. CARREON, CESE, Director, Public Information Office Tel. No. 929-3244, 927-9702 Loc.131; Cell phone: 09159111585 ______________________________________________________________________ 2 TARGETED DRUG SUSPECTS ARRESTED IN OROQUIETA SEARCHES P750,000 worth of shabu, drug paraphernalia, ammos seized Operatives of the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) arrested two targeted drug personalities during the implementation of two search warrants in Oroquieta City on August 19, 2016. PDEA Director General Isidro S. Lapeña said that the two lawful searches were implemented in Barangay Lower Lamac and Barangay Taboc Sur, Oroquieta City, Misamis Occidental by elements of PDEA Regional Office 10 (PDEA RO10) under Director Adrian Alvariño, at around 5:30 in the morning. Arrested during the operation were Jaime Cabilando, alias Kandong/Manong; and Lourdes Badenas Legaspi, alias Oding, both included in the list of targeted drug personalities of PDEA RO10; Jimmer Cabilando; and Milky Roycem Balolong. Seized inside the suspects’ houses were a total of 30 transparent plastic sachets containing methamphetamine hydrochloride, or shabu, weighing more or less 150 grams worth P750,000, various drug paraphernalia, 23 pieces of magazines containing 5.56mm ammunition, one cal. 45 magazine containing 10 pieces of live ammunition, P508,572 cash, one passbook and one blue box of different kinds of jewelries worth approximately millions of pesos. The arrested suspects will be charged for violation of Section 11 (Possession of Dangerous Drugs) and Section 12 (Possession of Drug Paraphernalia), Article II, of Republic Act 9165, or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002. -

TACR: Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41076-01 February 2011 Republic of the Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) Volume 1: Executive Summary Prepared by Katahira & Engineers International In association with Schema Konsult, Inc. and DCCD Engineering Corporation For the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Lao PDR and This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Governments concerned, and ADB and the Governments cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY PORT AREA, MANILA ASSET PRESERVATION COMPONENT UNDER TRANCHE 1, PHASE I ROAD SECTOR INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM (RSIDIP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY in association KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS with SCHEMA KONSULT, DCCD ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL INC. CORPORATION Road Sector Institutional Development and Investment Program (RSIDIP): Executive Summary TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ................................................... ES-1 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE PPTA............................................................ ES-1 3. SCOPE OF THE STUDY ................................................................. ES-2 4. SELECTION OF ROAD SECTIONS FOR DESIGN IN TRANCHE 1 ....... ES-3 5. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .............................................................. ES-8 -

PHI-OCHA Logistics Map 04Dec2012

Philippines: TY Bopha (Pablo) Road Matrix l Mindanao Tubay Madrid Cortes 9°10'N Carmen Mindanao Cabadbaran City Lanuza Southern Philippines Tandag City l Region XIII Remedios T. Romualdez (Caraga) Magallanes Region X Region IX 9°N Tago ARMM Sibagat Region XI Carmen (Davao) l Bayabas Nasipit San Miguel l Butuan City Surigao Cagwait Region XII Magsaysay del Sur Buenavista l 8°50'N Agusan del Norte Marihatag Gingoog City l Bayugan City Misamis DAVAO CITY- BUTUAN ROAD Oriental Las Nieves San Agustin DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA MONKAYO TRENTO SAN FRANS BUTUAN DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Prosperidad TAGUM CITY 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA 102km/2.5hr 42km/1.5hr 12km/15mns 8°40'N 120km/2.45hr 60km/1hr 30km/45mns. 18kms/15mns Claveria Lianga MONKAYO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr 40km/1hr 22km/30mns Esperanza TRENTO SAN FRANCISCO 200km/4hr 140km/3 hr 110km/2.5hr 98km/2.hr 80km/1.45hr 58km/1.5hr BUTUAN 314km/6hr 254km/5hr 224km/4hr 212km/3.5hr 194km/3hr 172km/2.45hr 114km/2hr l Barobo l 8°30'N San Luis Hinatuan Agusan Tagbina del Sur San Francisco Talacogon Impasug-Ong Rosario 8°20'N La Paz l Malaybalay City l Bislig City Bunawan Loreto 8°10'N l DAVAO CITY TO - LORETO, AGUSAN DEL SUR ROAD DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN TRENTO STA. JOSEFA VERUELA LORETO DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Lingig TAGUM CITY Cabanglasan Trento 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN Veruela Santa Josefa TRENTO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr STA. -

Covers Republic Act Numbers 11167-11372

Senate of the Philippines Linkages Update Volume 12 No. 3 17th Congress Series of 2019 This Linkages Update aims to provide information on legislations approved and enacted into law, bills passed on third reading by the Senate, outputs of Forums conducted by ILS, and other concerns of national importance. Presented in this issue are the Laws Passed during the Seventeenth Congress covering the period January 2019 to June 2019. This publication is a project of the Institutional Linkages Service (ILS) under the External Affairs and Relations Office. Contents Covers Republic Act Nos. 11167-11372 Researched and Encoded by : Ma. Teresa A. Castillo Reviewed and Administrative Supervision by : Dir. Julieta J. Cervo, CPA, DPA Note: The contents of this publication are those that are considered Important by the author/researcher and do not necessarily reflect those of the Senate, of its leadership or of its individual members. The Institutional Linkages Service is under the External Affairs and Relations headed by Deputy Secretary Enrique Luis D. Papa and Executive Director Diana Lynn Le-Cruz. Covers Republic Act Numbers 11167-11372 Provided below are the laws passed and approved by the President of the Philippines during the 3rd Regular Session of the 17th Congress: REPUBLIC ACT NO. 11167 “AN ACT INCREASING THE BED CAPACITY OF THE BILIRAN PROVINCIAL HOSPITAL IN ITS PROPOSED RELOCATION SITE IN BARANGAY LARRAZABAL, MUNICIPALITY OF NAVAL, PROVINCE OF BILIRAN, FROM SEVENTY-FIVE (75) TO TWO HUNDRED (200) BEDS, AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR” APPROVED INTO LAW ON JANUARY 3, 2019 REPUBLIC ACT NO. 11168 “AN ACT ALLOWING HOME ECONOMICS GRADUATES TO TEACH HOME ECONOMICS SUBJECTS AND HOME ECONOMICS-RELATED TECHNICAL-VOCATIONAL SUBJECTS IN ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, RESPECTIVELY, CONSISTENT WITH SECTION 8 OF REPUBLIC ACT NO. -

CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986

Date Printed: 01/14/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 29 Tab Number: 37 Document Title: THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986 Document Country: PHI Document Language: ENG IFES 10: CON00159 Republic of the Philippines The Constitutional Commission of 1986 The- Constitution ,- of.the- -Republic of tile Philippines Adopted by , - . THE CONSTITIJTIONAL COMMISSION OF 1986 At the National Government-Center, Quezon City, Philjppincs, on the fifteenth day of October, Nineteen hundred and eighty-six 198(j THE CONSTITUTION· OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES P REAM B LE. We; toe sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty Cod, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promotl' the common good, conserve and. develop· our patrimony, and secure- to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law"and a regime of truth, justice, free dom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and piomulgatethis Consti tution. ARTICLE I NATIONAL TERRITORY The national territorycomprise~ the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein,' and all other territories over which the. Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction, .consisting of its terrestrial, fluvial, and aerial domains, including its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, the insula~ shelves, and other submarine areas. The waters aroilnd, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and. dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines. ARTICLE II r DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLE15 AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES Section I .. The Philippines is a democratic and· republican State.