A Study of Dentate and Edentulous Mandibles Roberta A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Appearance of Foramen in the Internal Aspect of the Mental

Okajimas Folia Anat. Jpn., 82(3): 83–88, November, 2005 The Appearance of Foramen in the Internal Aspect of the Mental Region of Mandible from Japanese Cadavers and Dry Skulls Under Macroscopic Observation and Three-dimensional CT Images By Shunji YOSHIDA1),TaisukeKAWAI2),KoichiroOKUTSU2), Takashi YOSUE2), Hitoshi TAKAMORI3), Masataka SUNOHARA and Iwao SATO1) 1Department of Anatomy, 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology School of Dentistry at Tokyo, 3Oral Implant Clinic, Nippon Dental University at Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan – Received for Publication, June 28, 2005 – Key Words: Lingual foramen, CT, Mandible Summary: The lingual canal with foramen displays different appearances on the internal surfaces of mandible as con- firmed by macroscopic observation and computerized tomography (CT). The lingual canal was observed in the inside of mental region run to the outside of lingual foramen, which is extend internally from mandibular canal in right and left sides of the mandible in cadavers (13 sides out of 88 sides) and in dry skulls (43 out of 94 sides) examined. The spinal foramen connected with mental canal occurred at the midline of mandible in 6 cases (6 out of 47 cases) in dry skulls. In this small foramen, the inferior alveolar artery give some branches to the inside of mental region at the anterior man- dible and which may be run pass through the lingual canal to the lingual foramen, where they emerge to enter the mylohyoid or anterior belly of digastric muscles. The observations of these are important considerations for surgical placement of dental implants in the region in the mandible. The anatomical location, course and arrange- treatments. -

Course of the Maxillary Artery Through the Loop Of

Anomalous course of maxillary artery Rev Arg de Anat Clin; 2013, 5 (3): 235-239 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Case Report COURSE OF THE MAXILLARY ARTERY THROUGH THE LOOP OF THE AURICULOTEMPORAL NERVE Kavya Bhat, Sampath Madhyastha*, Balakrishnan R Department of Anatomy, Kasturba Medical College, Bejai Campus, Mangalore, Manipal University, India RESUMEN INTRODUCTION Las variaciones en el curso de la arteria maxilar se describen a menudo, con sus relaciones con el Maxillary artery is one of the larger terminal músculo pterigoideo lateral. En el presente caso branches of the external carotid artery, arises informamos una variación exclusiva en el curso de la behind the neck of the mandible, within the arteria maxilar que no fue publicada antes. En un substance of the parotid gland. It then crosses cadáver masculino de 75 años arteria maxilar derecho the infratemporal fossa to enter the pterygo- estaba pasando por el bucle del nervio auriculo- palatine fossa through pterygo-maxillary fissure. temporal. La arteria meníngea media provenía de la The course of the artery is divided into three arteria maxilar con un bucle del nervio auriculo- temporal. La arteria maxilar pasaba profunda con parts by the lateral pterygoid muscle. The first respecto al nervio dentario inferior pero superficial al (mandibular) part runs horizontally, parallel to nervio lingual. El conocimiento de estas variaciones es and slightly below the auriculo-temporal nerve. importante para el cirujano y también serviría para This part of the artery runs superficial (lateral) to explicar la posible participación de estas variaciones the lower head of lateral pterygoid muscle. The en la etiología del dolor mandibular. -

Mechanics in the Production of Mandibular Technique. I

Mechanics in the Production of Mandibular Fractures: A Study with the "Stresscoat' Technique. I. Symphyseal Impacts DONALD F. HUELKE Department of Anatomy, University of Michigan Medical School Ann Arbor, Michigan A recent study of 319 case histories of mandibular fractures by Hagan and Huelke' has shown that certain areas of the jaw are fractured more often than others and that the incidence of certain mandibular fractures is greater when the blow is directed to specific regions of the jaw. Relatively little is known about the response of the mandi- ble to impact, except that, when the magnitude of a blow is sufficient, the bone will break. How does the mandible fracture, and what are the mechanisms involved? These questions have not been answered because of the lack of experimental data. Obtaining these data is an engineering problem involving stresses, strains, impacts, energies, and forces, and thus engineering techniques must be used. This report, the first of a series of studies on the mechanism of mandibular frac- tures, presents data on forces and impacts applied to the chin point of the mandible and the resultant deformations of the bone. The results of these tests are correlated with certain clinical findings. Terminology.-Throughout this report certain terminology generally used in engi- neering will be employed. Some of these terms need to be defined. The term force is defined as a push or pull. The various types of force are illustrated in Figure 1. Ten- sile forces (tension) tend to pull an object apart; compressive forces (compression) push the particles forming an object together, while shearing forces make one part of an object slide over another part of the same object. -

Download The

Review of the arterial anatomy in the anterior mandible Review of the arterial vascular anatomy for implant placement in the anterior mandible Abstract Objective José Carlos Balaguer Marti,* Juan Guarinos,† The placement of implants in the anterior region of the mandible is not Pedro Serrano Sánchez,† Amparo Ruiz Torner,* free of risk and can even sometimes be life-threatening. The aim of this * * David Peñarrocha Oltra & Miguel Peñarrocha Diago article is to review the anatomy of the anterior mandible regarding the *Department of Stomatology, Faculty of Medicine and placement of implants in this region. Odontology, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain † Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine and Materials and methods Odontology, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain An anatomical study was conducted in cadavers to analyze the various Corresponding author: anatomical structures of the anterior region of the mandible. A literature review was also undertaken. Dr. David Peñarrocha Oltra Clínicas odontológicas Gascó Oliag, 1 46021 Valencia Results Spain The sublingual and submental arteries are the main supply of the sublin- T & F +34 963 86 4139 [email protected] gual region. These arteries are usually located at a safe distance from the alveolar ridge, but in cases of severe atrophy or anatomical variations, there may be an increased risk of damage during the placement of dental How to cite this article: implants and serious complications may arise. Balaguer Marti JC, Guarinos J, Serrano Sánchez P, Ruiz Torner A, Peñarrocha Oltra D, Peñarrocha Diago M. Conclusion Review of the arterial vascular anatomy for implant placement in the anterior mandible. The injury of the vessels in the floor of the mouth could lead to severe complications. -

Assessment of Bone Channels Other Than the Nasopalatine Canal in the Anterior Maxilla Using Limited Cone Beam Computed Tomography

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) Surg Radiol Anat (2013) 35:783–790 DOI 10.1007/s00276-013-1110-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessment of bone channels other than the nasopalatine canal in the anterior maxilla using limited cone beam computed tomography Thomas von Arx • Scott Lozanoff • Pedram Sendi • Michael M. Bornstein Received: 16 January 2013 / Accepted: 12 March 2013 / Published online: 29 March 2013 Ó Springer-Verlag France 2013 Abstract 1.31 ± 0.26 mm (range 1.01–2.13 mm). Gender and age Purpose The anterior maxilla, sometimes also called did not significantly influence the diameter. Accessory premaxilla, is an area frequently requiring surgical inter- canals were found palatal to all anterior teeth, but most ventions. The objective of this observational study was to frequently palatal to the central incisors. In 56.7 %, the identify and assess accessory bone channels other than the accessory canals curved superolaterally and communicated nasopalatine canal in the anterior maxilla using limited with the ipsilateral alveolar extension of the canalis cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). sinuosus. Methods A total of 176 cases fulfilled the inclusion cri- Conclusions The study confirms the presence of bone teria comprising region of interest, quality of CBCT image, channels within the anterior maxilla other than the naso- and absence of pathologic lesions or retained teeth. Any palatine canal. More than half of these accessory bone bone canal with a minimum diameter of 1.00 mm other canals communicated with the canalis sinuosus. -

Maxillary Incisive Canal Characteristics: a Radiographic Study Using Cone Beam Computerized Tomography

Hindawi Radiology Research and Practice Volume 2019, Article ID 6151253, 5 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6151253 Research Article Maxillary Incisive Canal Characteristics: A Radiographic Study Using Cone Beam Computerized Tomography Penala Soumya ,1 Pradeep Koppolu ,2 Krishnajaneya Reddy Pathakota,3 and Vani Chappidi4 1 Department of Dentistry, Mahavir Institute of Medical Sciences, Vikarabad, Telangana, India 2Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, Dar Al Uloom University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 3Department of Peroiodontics, Sri Sai College of Dental Surgery, Vikarabad, India 4Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Sri Sai College of Dental Surgery, Vikarabad, Telangana, India Correspondence should be addressed to Penala Soumya; [email protected] Received 1 November 2018; Accepted 5 March 2019; Published 27 March 2019 Academic Editor: Paul Sijens Copyright © 2019 Penala Soumya et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background. Te incisive canal located at the midline, posterior to the central incisor, is an important anatomic structure of this area to be considered while planning for immediate implant placement in maxillary central incisor region. Te purpose of the present study is to assess incisive canal characteristics using CBCT sections. Materials and Methods. CBCT scans of 79 systemically healthy patients, with intact maxillary incisors, were evaluated by two calibrated and independent examiners. Assessments included (1) mesiodistal diameter, (2) labiopalatal diameter, (3) length of the incisive canal, (4) shape of incisive canal, and (5) width of the bone anterior to the incisive foramen. -

Chapter 2 Implants and Oral Anatomy

Chapter 2 Implants and oral anatomy Associate Professor of Maxillofacial Anatomy Section, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University Tatsuo Terashima In recent years, the development of new materials and improvements in the operative methods used for implants have led to remarkable progress in the field of dental surgery. These methods have been applied widely in clinical practice. The development of computerized medical imaging technologies such as X-ray computed tomography have allowed detailed 3D-analysis of medical conditions, resulting in a dramatic improvement in the success rates of operative intervention. For treatment with a dental implant to be successful, it is however critical to have full knowledge and understanding of the fundamental anatomical structures of the oral and maxillofacial regions. In addition, it is necessary to understand variations in the topographic and anatomical structures among individuals, with age, and with pathological conditions. This chapter will discuss the basic structure of the oral cavity in relation to implant treatment. I. Osteology of the oral area The oral cavity is composed of the maxilla that is in contact with the cranial bone, palatine bone, the mobile mandible, and the hyoid bone. The maxilla and the palatine bones articulate with the cranial bone. The mandible articulates with the temporal bone through the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The hyoid bone is suspended from the cranium and the mandible by the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles. The formation of the basis of the oral cavity by these bones and the associated muscles makes it possible for the oral cavity to perform its various functions. -

Parts of the Body 1) Head – Caput, Capitus 2) Skull- Cranium Cephalic- Toward the Skull Caudal- Toward the Tail Rostral- Toward the Nose 3) Collum (Pl

BIO 3330 Advanced Human Cadaver Anatomy Instructor: Dr. Jeff Simpson Department of Biology Metropolitan State College of Denver 1 PARTS OF THE BODY 1) HEAD – CAPUT, CAPITUS 2) SKULL- CRANIUM CEPHALIC- TOWARD THE SKULL CAUDAL- TOWARD THE TAIL ROSTRAL- TOWARD THE NOSE 3) COLLUM (PL. COLLI), CERVIX 4) TRUNK- THORAX, CHEST 5) ABDOMEN- AREA BETWEEN THE DIAPHRAGM AND THE HIP BONES 6) PELVIS- AREA BETWEEN OS COXAS EXTREMITIES -UPPER 1) SHOULDER GIRDLE - SCAPULA, CLAVICLE 2) BRACHIUM - ARM 3) ANTEBRACHIUM -FOREARM 4) CUBITAL FOSSA 6) METACARPALS 7) PHALANGES 2 Lower Extremities Pelvis Os Coxae (2) Inominant Bones Sacrum Coccyx Terms of Position and Direction Anatomical Position Body Erect, head, eyes and toes facing forward. Limbs at side, palms facing forward Anterior-ventral Posterior-dorsal Superficial Deep Internal/external Vertical & horizontal- refer to the body in the standing position Lateral/ medial Superior/inferior Ipsilateral Contralateral Planes of the Body Median-cuts the body into left and right halves Sagittal- parallel to median Frontal (Coronal)- divides the body into front and back halves 3 Horizontal(transverse)- cuts the body into upper and lower portions Positions of the Body Proximal Distal Limbs Radial Ulnar Tibial Fibular Foot Dorsum Plantar Hallicus HAND Dorsum- back of hand Palmar (volar)- palm side Pollicus Index finger Middle finger Ring finger Pinky finger TERMS OF MOVEMENT 1) FLEXION: DECREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 2) EXTENSION: INCREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 3) ADDUCTION: TOWARDS MIDLINE -

Anatomy of Mandibular Vital Structures. Part I: Mandibular Canal and Inferior Alveolar Neurovascular Bundle in Relation with Dental Implantology

JOURNAL OF ORAL & MAXILLOFACIAL RESEARCH Juodzbalys et al. Anatomy of Mandibular Vital Structures. Part I: Mandibular Canal and Inferior Alveolar Neurovascular Bundle in Relation with Dental Implantology Gintaras Juodzbalys1, Hom-Lay Wang2, Gintautas Sabalys1 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kaunas University of Medicine, Lithuania 2Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Michigan, USA Corresponding Author: Gintaras Juodzbalys Vainiku 12 LT- 46383, Kaunas Lithuania Phone: +370 37 29 70 55 Fax: +370 37 32 31 53 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Objectives: It is critical to determine the location and configuration of the mandibular canal and related vital structures during the implant treatment. The purpose of the present paper was to review the literature concerning the mandibular canal and inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle anatomical variations related to the implant surgery. Material and Methods: Literature was selected through the search of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane electronic databases. The keywords used for search were mandibular canal, inferior alveolar nerve, and inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle. The search was restricted to English language articles, published from 1973 to November 2009. Additionally, a manual search in the major anatomy, dental implant, prosthetic and periodontal journals and books were performed. Results: In total, 46 literature sources were obtained and morphological aspects and variations of the anatomy related to implant treatment in posterior mandible were presented as two entities: intraosseous mandibular canal and associated inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle. Conclusions: A review of morphological aspects and variations of the anatomy related to mandibular canal and mandibular vital structures are very important especially in implant therapy since inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle exists in different locations and possesses many variations. -

Anatomical Study of Nutrient Vessels in the Condylar Neck Accessory Foramina

Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-019-02304-w ORIGINAL ARTICLE Endosteal blood supply of the mandible: anatomical study of nutrient vessels in the condylar neck accessory foramina Matthieu Olivetto1 · Jérémie Bettoni1 · Jérôme Duisit2,3 · Louis Chenin4 · Jebrane Bouaoud1 · Stéphanie Dakpé1,5 · Bernard Devauchelle1,5 · Benoît Lengelé2,3 Received: 23 December 2018 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 © Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose In the mandible, the condylar neck vascularization is commonly described as mainly periosteal; while the endosteal contribution is still debated, with very limited anatomical studies. Previous works have shown the contribution of nutrient vessels through accessory foramina and their contribution in the blood supply of other parts of the mandible. Our aim was to study the condylar neck’s blood supply from nutrient foramina. Methods Six latex-injected heads were dissected and two hundred mandibular condyles were observed on dry mandi- bles searching for accessory bone foramina. Results Latex-injected dissections showed a direct condylar medular arterial supply through foramina. On dry mandi- bles, these foramina were most frequently observed in the pterygoid fovea in 91% of cases. However, two other accessory foramina areas were identifed on the lateral and medial sides of the mandibular condylar process, confrming the vascular contribution of transverse facial and maxillary arteries. Conclusions The maxillary artery indeed provided both endosteal and periosteal blood supply to the condylar neck, with three diferent branches: an intramedullary ascending artery (arising from the inferior alveolar artery), a direct nutrient branch and some pterygoid osteomuscular branches. Keywords Condylar neck · Mandibular condyle · Mandible blood supply · Arterial vascularization · Maxillary artery Introduction condylar neck blood supply is still debated and has been poorly studied. -

Title Three-Dimensional Analysis of Incisive Canals in Human

Three-dimensional analysis of incisive canals in Title human dentulous and edentulous maxillary bones Author(s) 福田, 真之 Journal , (): - URL http://hdl.handle.net/10130/3615 Right Posted at the Institutional Resources for Unique Collection and Academic Archives at Tokyo Dental College, Available from http://ir.tdc.ac.jp/ Three-dimensional analysis of incisive canals in human dentulous and edentulous maxillary bones Masayuki Fukuda Department of Anatomy, Tokyo Dental College 1 Abstract [Objectives] The purpose of this study was to reveal the structural properties that need to be considered in dental implant treatment, by investigating differences between dentulous and edentulous maxillae in three-dimensional (3D) microstructure of the incisive canals (IC) and their surrounding bone. [Materials and Methods] A total of 40 maxillary bones comprising 20 dentulous maxillae and 20 edentulous maxillae were imaged by micro-CT for 3D observation and measurement of the IC and alveolar bone in the anterior region of the IC. [Results] The Y-morphology canal was most frequently observed at 60% in dentulous maxilla and 55% in edentulous maxilla. There was a significant difference between dentulous and edentulous maxillae in IC diameter and volume, but no significant difference between the two in the major axis of the ICs. [Conclusions] The anatomic structure surrounding the IC has limited area for implant placement. Therefore, where esthetic and long-term maintenance requirements are taken into account, careful attention is needed when setting the placement position. Also, due to the resorption of bone, edentulous maxillae have a different IC morphology from dentulous maxillae, and therefore a cautious approach is required. -

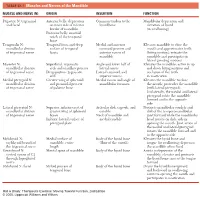

1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible

0350 ch 23-Tab 10/12/04 12:19 PM Page 1 Chapter 23: The Temporomandibular Joint 1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible MUSCLE AND NERVE (N) ORIGIN INSERTION FUNCTION Digastric N: trigeminal Anterior belly: depression Common tendon to the Mandibular depression and and facial on inner side of inferior hyoid bone elevation of hyoid border of mandible (in swallowing) Posterior belly: mastoid notch of the temporal bone Temporalis N: Temporal fossa and deep Medial and anterior Elevates mandible to close the mandibular division surface of temporal coronoid process and mouth and approximates teeth of trigeminal nerve fascia anterior ramus of (biting motion); retracts the mandible mandible and participates in lateral grinding motions Masseter N: Superficial: zygomatic Angle and lower half of Elevates the mandible; active in up mandibular division arch and maxillary process lateral ramus and down biting motions and of trigeminal nerve Deep portion: zygomatic Lateral coronoid and occlusion of the teeth arch superior ramus in mastication Medial pterygoid N: Greater wing of sphenoid Medial ramus and angle of Elevates the mandible to close mandibular division and pyramidal process mandibular foramen the mouth; protrudes the mandible of trigeminal nerve of palatine bone (with lateral pterygoid). Unilaterally, the medial and lateral pterygoid rotate the mandible forward and to the opposite side Lateral pterygoid N: Superior: inferior crest of Articular disk, capsule, and Protracts mandibular condyle and mandibular division greater wing of sphenoid condyle disk of the temporomandibular of trigeminal nerve bones Neck of mandible and joint forward while the mandibular Inferior: lateral surface of medial condyle head rotates on disk; aids in pterygoid plate opening the mouth.