31 Format. Hum-Analyzing Amish Tripathi's 'Shiva Trilogy'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues of War in the Immortals of Meluha

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in (Impact Factor : 5.9745 (ICI) KY PUBLICATIONS RESEARCH ARTICLE ARTICLE Vol. 5. Issue.1., 2018 (Jan-Mar) ISSUES OF WAR IN THE IMMORTALS OF MELUHA RITIKA PAUL Research Scholar, Department of English, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT The issue of war had been relevant in all ages which also figures prominently in the Immortals of Meluha. It seems to question war on the one hand and draws attention towards the present on the other. Wars are an organized and prolonged conflict that is carried out by states. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, social disruption and economic destruction. It is an intentional widespread conflict between political communities. War leads to destruction of human and natural RITIKA PAUL resources. War leads to pervasive violence in the name of justice and revenge. In the novel various battles are fought between Guna and Prakritis, Suryavanshi and Chandravanshi, Naga and Suryavanshi. Keywords: Meluha, Shiva, war. Introduction Amish Tripathi is a finance professional educated from Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta. He is passionate about history, mythology and philosophy. He is an avid reader of history and his inspirations for the story ranged from writers like Graham Hancock and Gregory Possehl to the Amar Chitra Katha series of Indian comics. The Immortals of Meluha, the first novel in Shiva Trilogy by Amish Tripathi, is also heavily embedded in Indian mythology. The Shiva Trilogy comprises three parts: The Immortals of Meluha, The Secrets of the Nagas and The Oath of Vayuputras. -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Modernisation of Myth in Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy and Ram Chandra Series Priti M. Padsumbiya Dr Ankit Gandhi Research Scholar Assistant Professor Dept. of English Dept. of English Madhav University, Sirohi, Rajasthan Madhav University, Sirohi, Rajasthan V o l u m e . 3 I s s u e 4 F e b r u a r y - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT Each extraordinary human civilization has its own fortune of folklore. Egypt, Rome, Greece, India, China and different societies are the exemplary models. Every one of them, throughout history, made old stories, network customs and social convictions which prompted the making of tremendous collections of mythology. India has most likely the most extravagant storage facility of folklore and legends on the planet. It is encouraged from incalculable sources and safeguarded in the four Vedas , the Upanishads, the two stories, the eighteen fundamental Purans and manychants, plays, verse, figures ,move, music and folklore. The underlying foundations of India‟s incredible past go before the Aryans to the Dravidians and even -

Application of Langinus' Resources of Sublimity in Amish Tripathi's The

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-2, December 2019 Application of Langinus’ Resources of Sublimity in Amish Tripathi’s The Immortals of Meluha R. Manikandan, M. R. Bindu Abstract: Longinus, besides being one of the most famous III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ancient philosophers, contributed enormously to the field of art GRANDEUR OF THOUGHTS and literature; his concept of ‘Sublime’ which he introduced in his path-breaking work ‘On the Sublime’, written in epistolary The author has used a number of grand concepts— they are form and addressing Posthunius Terentianus, has constantly simple, yet aesthetically appealing to the been used to evaluate literature over the years. This paper studies readers—throughout the novel to make it sublime. For Amish Tripathi’s ‘The Immortals of Meluha’, the first of the instance, Meluhans are obsessive with the rules of war; they three novels of his Shiva Trilogy, using the five parameters that never kill the people who are begging for mercy, for them, it Longinus set forth to appraise if a work of literature has is unethical to attack an unarmed man, a swordsman from achieved sublimity or not. Written in simple, yet effective Meluhan camp does not attack a person below his waist. The language, the fantasy retelling of the story of Indian nobleness of Meluha is clearly shown by the words uttered by mythological God Lord Shiva, The Immortals of Meluha has Nandi “We deal honourably even with those are uplifting thoughts and the capacity to kindle readers’ emotions dishonourable, like the Sun we never take from anyone but which Longinus propagated as two of the major qualities of always give to others” (40). -

Ethical Wisdom and Philosophical Judgment in Amish Tripathi's the Oath of Vayuputras

Linguistics and Literature Studies 1(1): 20-31, 2013 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2013.010104 Ethical Wisdom and Philosophical Judgment in Amish Tripathi's The Oath of Vayuputras Lata Mishra Department of English Government KRG Autonomous PG Girls' College Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract This paper considers 'culture' as a framework in of good and evil, as perceived in Indian society. The which people live their lives and communicate shared concluding novel, The Oath of Vayuputras, argues and to a meanings with each other. Culture has been a dynamic great extent convinces that the culture of the nation, that system through which a society constructs, represents, enacts ignores the Laws of Nature, violates it, while the one that and understands itself. The research documents the way follows Laws of Nature leads its nation towards human consciousness cognizes and registers the world enlightenment. For fulfilling, harmonious and progressive around her/him. 'The Shiva Trilogy" authored by Amish life one is required to live in accordance with Laws of Nature Tripathi combines the narrative excess with philosophical or Dharma. The trilogy combines the narrative excess with debate. The fiction depicts that the culture evolves as men philosophical debate. sacrifice their duty (swadharma) for the greater good, Amish recreates the myth of Shiva, Ganesh, Sati and Kali Universal Dharma. The Oath of Vayuputras, enlivens through his study of all spheres of Indian life and literature. consciousness and promotes the experience of a new sense of He makes Shiva myth appealing and intelligible to the Self. -

Representation and Anthropomorphism of Mythical Characters in Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy

International Journal Online of Humanities (IJOHMN) ISSN: 2395-5155 Volume 6, Issue 1, February 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24113/ijohmn.v6i1.162 Humanly Gods or Godly Humans: Representation and Anthropomorphism of Mythical Characters in Amish Tripathi’s Shiva Trilogy Aritra Basu M.Phil. Research Scholar University of Delhi Delhi, India [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to analyse the representation of mythical characters in the three novels by Amish Tripathi, namely The immortals of Meluha, The secret of the Nagas and The oath of the Vayuputras. The protagonist is a human being, Shiva, whose bildungsroman through the trilogy transforms him into a God, but without actually changing any of his physical attributes. Thus, at the level of anthropomorphism, this method of representation sheds light on the humane aspect of the divinity. From a perspective of feminist understanding of disability, the character of Kali would be studied, as an initial outcast to an important character in the last two books. Thus, this paper would conclude that Tripathi attempts at a vision of inclusivity, by his clever techniques of the representation of the disabled and the divine alike. Keywords: Anthropomorphism, Disability, Myth, History, Marginalisation. www.ijohmn.com 96 International Journal Online of Humanities (IJOHMN) ISSN: 2395-5155 Volume 6, Issue 1, February 2020 The larger-than-life representation of characters with a divine prospect has been the signature move of Indian epics, legends, Vedas and Upanishads. While some of them were born out of a union between a God and a human, others were avatars or versions of Gods themselves. -

6.03(SJIF) Research Journal of English (RJOE)Vol-5, Issue-4, 2020

Oray’s Publications Impact Factor: 6.03(SJIF) Research Journal Of English (RJOE)Vol-5, Issue-4, 2020 www.rjoe.org.in An International Peer-Reviewed English Journal ISSN: 2456-2696 Indexed in: International Citation Indexing (ICI), International Scientific Indexing (ISI), Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI) Google Scholar &Cosmos. ______________________________________________________________________________ MYTHICAL REPRESENTATION OF THE WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF AMISH TRIPATHI ___________________________________________________________________________ Nirmla Rani Research Scholar Baba Mastnath University Rohtak, Haryana Research Guide: Dr. J. k. Sharma ___________________________________________________________________________ Abstract This paper explores the feminine virtuosity in the novels of Amish Tripathi.. Many women were given equal status to men even in the ancient civilization. There are so many examples of women, where women fought every challenges of their life and stood example as to the new generation. In the novels of Amish Tripathi women have been presented as doctors, worriers and artists etc. There are so many characters like Sati, Aayurwati and Sita who played different roles in the society. Some of them became the reason to reform the society. Because of Sati only, Shiva, the leader of Meluhans, want to reform the Vikrama system of society. There were women, who brought the change in society. Author Amish Tripathi has presented the women characters very artistically in his novels. Sati and Sita, both do their best in the society. Their presence in the story brings a new life to every character. Sati, is a skilled warrior and at every place, she leaves a mark of her presence. This research paper provides some significance and insight on virtues and ethical development from the ancient Indian philosophical perspective. -

Indian Scholar

ISSN 2350-109X Indian Scholar www.indianscholar.co.in An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal PORTRAYAL OF MYTHOLOGY IN AMISH TRIPATHI’S "THE IMMORTAL OF MELUHA" S. Sumathi Assistant Professor Department of English D.K.M. College for Women Vellore-1 All the literature of our world, are the outputs of the human emotions. Indian English literature is not essentially different in kind from the other Indian literatures. Its writers have made the most significant contribution in the fields of poetry, fiction, drama, short story, biography and autobiography. Indian English Literature is deeply rooted in our geographical climate and cultural beliefs. The Indian English novels were developed as a subaltern awareness; as a response to break away from the colonial literature. Hence the post-colonial Indian literature witnessed a revolution against the idiom which the colonial writers followed. However the Indian English writers started employing the techniques of mixed language, magic realism garnished with native themes. Hence from a post-colonial era Indian English literature ushered into the contemporary and then the post-modern era. The saga of the Indian English novel therefore stands as the tale of changing tradition, the story of changing India. The history of Indian English novel, a journey which began long back has witnessed a lot of alteration to gain the current stylish delineation. In the past few years many prominent writers have made a mark on the Indian Diaspora. Later, the concept of Indian English novel or rather the concept of Indians writing in English came much advanced and it is with the coming of Raja Rao, R.K.Narayan,Mulk Raj Anand, the journey of the Indian English Novel began. -

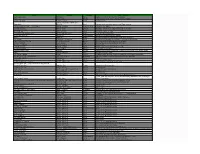

1. the Analysis & Use of Financial Statements White GI ; Fried D

1. The Analysis & Use of Financial Statements White G.I ; Fried D ; Sondhi A.C 2. 10 Natural Forces for Business Success:Harnessing the Energy for Positive Impact Garber P.R 3. The 100 Minutes Marketing Managers Nag A 4. 101 Best Resumes To Sell Yourself Block J A 5. 101 Smart Questions to ASK ON YOUR INTERVIEW Fry R 6. 101 Survival Tips for Your Business Griffiths A 7. 101 Ways to Captivate A Business Audience Gaulke S 8. The 11 Immutable Laws of Internet Branding Ries L ; Ries A L 9. 1800 Runs Brand Sale Khel Mein Kapoor J 10. 2 States:The Story of my Marriage Bhagat C 11. 2001 Quiz Book Sabharwal G ; Dube H 12. 2002 Ways to Find,Attract and Keep a Mate Haynes C ; Edwards D 13. The 21 Indispensable Qualities of a Leader Maxwell J 14. 21 Steps to PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT 15. 21st Century Management Haynes W ; Mukherjee S ; Specimen 16. The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing Ries A L ; Trout J 17. 25 Stupid Mistakes you don't want to make mistake in the stock market Rye D.E 18. 27 BRAND PRACTICES Kapoor J 19. The 3 Mistakes of My Life Bhagat C 20. 360 Degree Feedback and Assessment & Development Centres ( Vol.3) Rao, T.V. ; Chawla N 21. 360 Degree Feedback:A Management Tool Ward 22. 3D Graphics & Animation Giambruno M 23. 3D STUDIO MAX 3; Professional animation Jones A ; Bonney S 24. 3ds Max 6 Bible Murdock K L 25. 3Merchandising : Concepts and Cases Sreedhar G V S 26. -

A Study on the Scientific Approach Towards Vedic Shaivism in Amish Tripathi's the Shiva Trilogy

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 A Study on the Scientific Approach towards Vedic Shaivism in Amish Tripathi’s The Shiva Trilogy Sukanya Chakravarty M.Phil Research Scholar Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University Arunachal Pradesh Abstract: Myth in Indian culture has always been an aura of curiosity. Indian mythology dates back to the times of Lord Rama, Lord Shiva and our firm beliefs in the divine. It also shares with us the stories of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The reality of Ramayana and Mahabharata as true historical events or just an epic story is still arguable. The archaeological excavations give its presence in the structures of the Indus Valley Civilization and the Harappa Cities. Amish Tripathi, the budding Indian writer focuses on such issues of historical relevance in myths. In his works we find the science behind the Vedic customs. The paper attempts to sketch the scientific superiority of the Meluhans people in the novel The Shiva Trilogy. It depicts their firm beliefs and application of medicines and science for practicing a better and healthy life. Somras an eternal drink of bliss is an effort made by the Meluhan scientists to uplift the mankind, whereas the irony is that in the process of making the somras they are indirectly destroying the Mother Nature which in a way means demolishing the mankind. Keywords: Vedic, Myth, Somras, Lord Shiva, Meluha The word ‘myth’ is derived from the Greek word ‘mythos’, which suggests story or word. Myths are moral tales usually set in distant past which are believed as true and which comprises of unearthly, supernatural or legendary characters. -

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Mera Naam Joker Abbas K.A Novel made into a film by and starring Raj Kapoor Zed Abbas, Zaheer Cricket autobiography of the former Pakistan cricket captain Things Fall Apart Achebe, Chinua Novel Nigerian writer Aciman, Alexander and Rensin, Twitterature Emmett Novel Famous works of fiction condensed to Twitter format The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Adams, Douglas Science Fiction a trilogy in four parts The Dilbert Future Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The Dilbert Principle Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The White Tiger Adiga, Aravind Novel won Booker Prize in 2008 Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Advaita Ashram (pub) Essay great saint and philosopher My Country, My Life Advani L.K. Autobiography former Deputy Prime Minister of India Byline Akbar M.J Essay famous journalist turned politician's collection of articles The Woods Alanahally, Shrikrishna Novel translation of Kannada novel Kaadu. Filmed by Girish Karnad Plain Tales From The Raj Allen, Charles (ed) Stories tales from the days of the British rule in India Without Feathers Allen, Woody Play assorted pieces by the Manhattan filmmaker The House of Spirits Allende, Isabelle Novel Chilean writer Celestial Bodies Alharthi, Jokha Novel Omani novel translated by Marilyn Booth An Autobiography Amritraj, Vijay Sports great Indian tennis player Brahmans and Cricket Anand S. Cricket Brahmin community's connection to cricket in the context of the movie Lagan Gauri Anand, -

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K. Singh Literary Criticism Z Realism in the Romances of Shakespeare Z Dynamics of Poetry in Fiction Z The Creative Contours of Ruskin Bond (ed.) Z A Passage to Shiv K. Kumar Z The Indian English Novel Today (ed.) Poetry Z So Many Crosses Z The Vermilion Moon Z In the Olive Green Z Lamhe (Hindi) Translation into Hindi Z Raat Ke Ajnabi: Do Laghu Upanyasa (Two novellas of Ruskin Bond – A Handful of Nuts and The Sensualist) Z Mahabharat: Ek Naveen Rupantar (Shiv K. Kumar’s The Mahabharata) The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Edited by Prabhat K. Singh The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium, Edited by Prabhat K. Singh This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Prabhat K. Singh All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4951-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4951-7 For the lovers of the Indian English novel CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 The Narrative Strands in the Indian English Novel: Needs, Desires and Directions Prabhat K. Singh Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 28 Performance and Promise in the Indian Novel in English Gour Kishore Das Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

A Critical Assessment of Amish Tripathi's Shiva Trilogy As a Seminal Piece of Popular Fiction

DAYDREAMING AND POPULAR FICTION: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF AMISH TRIPATHI’S SHIVA TRILOGY AS A SEMINAL PIECE OF POPULAR FICTION NEHA KUMARI DR. RAJESH KUMAR Research Scholar, Research Adviser Department of English University Professor V.B.U., Hazaribag, Department of English Jharkhand, INDIA. V.B.U., Hazaribag, Jharkhand, INDIA “Phntasy…can become a source of pleasure for the hearers and spectators at the performance of writer’s work.1” expounds Sigmund Freud, in an informal talk given in 1907 which was subsequently published in 1908 under the title Creative Writers and Day- Dreaming. In his discourse, he presented his idea on the relationship between unconscious fantasy and creative art. Notably, he presented this relationship centreing the “authors of novels, Romances and short-stories2” and not “the authors of epics and tragedies3” whom he refers to as “most highly esteemed by the critic4”. Thus, he talks about popular literature, literary works that have yet to pass through the test of time to certify its creative sustainability. Fantasy is the nucleus of Popular Literature which according to Freud “[he] (an adult) is expected not to go on playing or Phantasying any longer, but to act in a real world”. It may be the reason why Popular fiction or Genre fiction is usually looked down upon by academics (an adult) through the concept of the semi-educated mass reader vs. the highly educated class reader. Popular fiction must connect and satiate the literary appetite of the so called mass reader of popular fiction as opposed to class reader of literary fiction or artistic fiction.