Art and Architecture in Ladakh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladakh Studies 31 · ESSAYS

Ladakh Studies 31 · ESSAYS {}üº²¤.JÀÛP.uÛºÛ.¾.hÔGÅ.ÇÀôz.¢ôP.±ôGÅ.qü INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES 31 July 2014 ISSN 1356-3491 i ESSAYS · Ladakh Studies 31 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES Patron: Tashi Rabgias President: John Bray, 2001, 5-2-15 Oe, Kumamoto-shi, 862-0971, Japan [email protected] EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Secretary: Sonam Wangchok Kharzong, Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation, P.O. Box 105, Leh-Ladakh 194 101, India. Tel: +91-94 192 18 013, [email protected] Editor: Sunetro Ghosal Stawa Neerh P.O. Box 75 JBM Road, Amboli Leh-Ladakh 194 101 Andheri West India Mumbai 400 058 India [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer and Membership Secretary: Andrea Butcher, 176 Pinhoe Road, Exeter, Devon EX4 7HH, UK, [email protected], UK Mobile/Cell: +44-78 159 06 853 Webmaster: Seb Mankelow, [email protected], Ladakh Liaison Officer & Treasurer (Ladakh): Mohammed Raza Abbasi, 112 Abbassi Enclave, Changchik, Kargil-Ladakh, 194 103, India. Email:[email protected] Mobile/Cell: +91-94 191 76 599 ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Monisha Ahmed Gulzar Hussein Munshi Mona Bhan Tashi Ldawa Sophie Day Tashi Morup Mohammed Deen Darokhan Thupstan Norboo Kaneez Fathima Bettina Zeisler Blaise Humbert-Droz Martijn van Beek Since 1974, Ladakh (made up of Leh and Kargil districts) has been readily accessible for academic study. It has become the focus of scholarship in many disciplines including the fields of anthropology, sociology, art history, Buddhist studies, history, geography, environmental studies, ecology, medicine, agricultural studies, development studies, and so forth. After the first international colloquium was organised at Konstanz in 1981, there have been biennial colloquia in many European countries and in Ladakh. -

Economic Review” of District Leh, for the Year 2014-15

PREFACE The District Statistics and Evaluation Agency Leh under the patronage of Directorate of Economic and Statistics (Planning and Development Department) is bringing out annual publication titled “Economic Review” of District Leh, for the year 2014-15. The publication 22st in the series, presents the progress achieved in various socio-economic facts of the district economy. I hope that the publication will be a useful tool in the hands of planners, administrators, Policy makers, academicians and other users and will go a long way in helping them in their respective pursuit. Suggestions to improve the publication in terms of coverage, quality etc. in the future issue of the publication will be appreciated Tashi Tundup District statistics and Evaluation Officer Leh CONTENTS Page No. District Profile 1-6 Agriculture and Allied Activities • Agriculture 7-9 • Horticulture 10 • Animal Husbandry 11-13 • Sheep Husbandry 14-15 • Forest 16 • Soil Conservation 17 • Cooperative 17-18 • Irrigation 19 Industries and Employment • Industries 19-20 • Employment & Counseling Centre 20 • Handicraft/Handloom 21 Economic Infrastructure • Power 21-22 • Tourism 22-23 • Financial institution 24-25 • Transport and communication 24-27 • Information Technology 27-28 Social Sector • Housing 29 • Education 29-31 • Health 31-33 • Water Supply and Rural Sanitation 33 • Women and Child Development 34-36 1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 51 | 2020 the Murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a Few Related Monuments

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4361 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Nils Martin, “The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4361 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/emscat.4361 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments.... 1 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments. A glimpse into the politico-religious situation of Ladakh in the 14th and 15th centuries Les peintures murales du Lotsawa Lhakhang de Henasku et de quelques temples apparentés. Un aperçu de la situation politico-religieuse du Ladakh aux XIVe et XVe siècles Nils Martin Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, 51 | 2020 The murals of the Lotsawa Lhakhang in Henasku and of a few related monuments... -

03 Economic Review 2015-16

0 1 DISTRICT PROFILE Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. The district of Leh forms the Northern tip of the Indian Sub Continent. According to the Geographical experts, the district has several other features, which make it unique when compared with other parts of the Indian sub-continent. The district is the coldest and most elevated inhabited region in the country with altitude ranging from 2300 meters to 5000 meters. As a result of its high altitude locations, annual rainfall is extremely low. This low status of precipitation has resulted in scanty vegetation, low organic content in the soil and loose structure in the cold desert. But large-scale plantation has been going in the district since 1955 and this state of affairs is likely to change. The ancient inhabitants of Ladakh were Dards, an Indo- Aryan race. Immigrants of Tibet, Skardo and nearby parts like Purang, Guge settled in Ladakh, whose racial characters and cultures were in consonance with early settlers. Buddhism traveled from central India to Tibet via Ladakh leaving its imprint in Ladakh. Islamic missionaries also made a peaceful penetration of Islam in the early 16 th century. German Moravian Missionaries having cognizance of East India Company also made inroads towards conversion but with little success. In the 10 th century AD, Skit Lde Nemagon, the ruler of Tibet, invaded Ladakh where there was no central authority. -

PDF Evolution and Development of the Trade Route in Ladakh

RESEARCH ASSOCIATION for R AA I SS INTERDISCIPLINARY JUNE 2020 STUDIES DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3909993 Evolution and Development of the Trade Route in Ladakh: A Case-Study of Rock Carvings Dr. Khushboo Chaturvedi, Mr. Varun Sahai Assistant Professor, Amity University, India, [email protected] Assistant Professor, Amity University, India, [email protected] ABSTRACT: From the beginning of human history trade has been major source of growth of civilization and material culture. Economy was the main crux which caused Diasporas what disseminated cultures and religions on our planet. The Silk Road was one of the first trade routes to join the Eastern and the Western worlds. Ladakh also underwent the same process of evolution of trade although it was a difficult terrain but it provides access to travelers from central Asia and Tibet through its passes. Ladakh was a crossroads of many complexes of routes, providing choices for different sectors connecting Amritsar to Yarkand. Again, from Leh to Yarkand, there were several possible routes all converging at the Karakoram Pass. Comparative small human settlements in oases of Ladakh’s desert rendered hospitality to the travelers being situated as halting station on traditional routes. Indeed, such places (halts) were natural beneficiaries of generating some sort of revenues from travelers against the essential services provided to caravans and groups of traders and travelers. Main halts on these routes are well marked with petro-glyphs right from Kashmir to Yarkand and at major stations with huge rock carving of Buddhist deities. Petro-glyphs, rock carvings, inscriptions and monasteries, mani-walls and stupas found along the trekking routes, linking one place to other, are a clear indication that the routes were in-vogue used by caravan traders; these establishments were used as landmarks or guidepost for travelers. -

Registration No

List of Socities registered with Registrar of Societies of Kashmir S.No Name of the society with address. Registration No. Year of Reg. ` 1. Tagore Memorial Library and reading Room, 1 1943 Pahalgam 2. Oriented Educational Society of Kashmir 2 1944 3. Bait-ul Masih Magarmal Bagh, Srinagar. 3 1944 4. The Managing Committee khalsa High School, 6 1945 Srinagar 5. Sri Sanatam Dharam Shital Nath Ashram Sabha , 7 1945 Srinagar. 6. The central Market State Holders Association 9 1945 Srinagar 7. Jagat Guru Sri Chand Mission Srinagar 10 1945 8. Devasthan Sabha Phalgam 11 1945 9. Kashmir Seva Sadan Society , Srinagar 12 1945 10. The Spiritual Assembly of the Bhair of Srinagar. 13 1946 11. Jammu and Kashmir State Guru Kula Trust and 14 1946 Managing Society Srinagar 12. The Jammu and Kashmir Transport union 17 1946 Srinagar, 13. Kashmir Olympic Association Srinagar 18 1950 14. The Radio Engineers Association Srinagar 19 1950 15. Paritsarthan Prabandhak Vibbag Samaj Sudir 20 1952 samiti Srinagar 16. Prem Sangeet Niketan, Srinagar 22 1955 17. Society for the Welfare of Women and Children 26 1956 Kana Kadal Sgr. 1 18. J&K Small Scale Industries Association sgr. 27 1956 19. Abhedananda Home Srinagar 28 1956 20. Pulaskar Sangeet Sadan Karam Nagar Srinagar 30 1957 21. Sangit Mahavidyalaya Wazir Bagh Srinagar 32 1957 22. Rattan Rani Hospital Sriangar. 34 1957 23. Anjuman Sharai Shiyan J&K Shariyatbad 35 1958 Budgam. 24. Idara Taraki Talim Itfal Shiya Srinagar 36 1958 25. The Tuberculosis association of J&K State 37 1958 Srinagar 26. Jamiat Ahli Hadis J&K Srinagar. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Leh District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Leh District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone 01912431077,01912435425 Fax: 01912431077,01912435425 e-mail: [email protected] web- www.msmedijammu.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 1 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 2 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 3 2. District at a glance 4 to 6 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District 7 3. Industrial Scenario 7 3.1 Industry at a Glance 7 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 9 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 10 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.9 Service Enterprises 10 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 10 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 11 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 11 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 11 meeting 6 Prospects of training Programmes during 2012-13 12 7. Action plan for MSME Schemes during 2012-13 12 8. Steps to set up MSMEs 13 9. Additional information if any - 1 Brief Industrial Profile of Leh District 1. General Characteristics of the District HISTORY Leh (Ladakh) was known in the past by different names. It was called Maryul or low land by some Kha- chumpa by others. Fa- Hein referred to it as Kia-Chha and Hiuen Tsang as Ma-Lo-Pho. -

Political History of Ladakh ( Pre 9Th to 12 Th CE)

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.41, 2017 Political History of Ladakh ( Pre 9th to 12 th CE) Mohd Ashraf Dar Ph.D Research Scholar S.O.S in A.I.H.C & Archaeology, Vikram University, Ujjain (M.P.) JRF ICHR Abstract Ladakh is the Northern most division of Indian Union which falls in Jammu and Kashmir state. Generally the recorded history of Ladakh begins with the coming of Tibetans to Ladakh in the late 9th CE. This paper is an attempt to string together the Pre 9th political history and the post 9th political history of Ladakh till 12 th CE. For this purpose folk lore and oral traditions have been employed as well in order to logically fill the lacunae in the pre 9th CE history of Ladakh. This paper also provides a geographical glimpse of Ladakh. Keywords : Ladakh, Geographical, Political, Chronicle, Tibet, Ladakhi Kingdom. Introduction Ladakh is known by various names like Mar-yul 1 (The Red land), La-tags 2, Land of Lamas and the Moon city 3etc. In fact Ladakh has been named by many people on the basis of their first glimpse of the land. The `multinomial nature of Ladakh depicts its versatility in the geo-ethnic milieu of the world itself. Speaking in terms of geography, Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir state can be divided into seven parts, lower (Sham ), Upper (tod ), Central (Zhang ), Nubra, Chang-thang, Purig and Zanskar. But in typical geographical terms the whole region can be divided into three major sub geographical regions. -

Sino-Tibetan Relations 1990-2000: the Internationalisation of the Tibetan Issue

Sino-Tibetan Relations 1990-2000: the Internationalisation of the Tibetan Issue Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie dem Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften und Philosophie der Philipps-Universität Marburg vorgelegt von Tsetan Dolkar aus Dharamsala, Indien 29 Februar 2008 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dirk Berg-Schlosser Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Wilfried von Bredow Sino-Tibetan Relations 1990-2000: the Internationalisation of the Tibetan Issue Submitted by Tsetan Dolkar Political Science Department, Philipps University First Advisor: Professor Dr. Dirk Berg-Schlosser Second Advisor: Professor Dr. Wilfried von Bredow A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Social Sciences and Philosophy of Philipps University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Philipps University, Marburg 29 February 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement vi Maps viii List of Abbreviations xi PART I A GLIMPSE INTO TIBET’S PAST Chapter 1 Tibet: A Brief Historical Background 1 1.1.1 Introduction 1 1.1.2 Brief Historical Background 4 1.1.2.1 Tibetan Kings (624-842 AD) and Tang China (618-756 AD) 4 1.1.2.2 The Buddhist Revolution in Tibet (842-1247) and the Song Dynasty (960-1126) 8 1.1.2.3 The Sakya Lamas of Tibet (1244-1358) and the Mongol Empire (1207-1368) 10 1.1.2.4 The Post-Sakya Tibet (1337-1565) and the Ming China (1368-1644) 11 1.1.2.5 The Gelugpa’s Rule (1642-1950) and the Manchu Empire (1662-1912) 13 1.1.2.6 Tibet in the Twentieth Century 19 -

District Profile

1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. The district of Leh forms the Northern tip of the Indian Sub Continent. According to the Geographical experts, the district has several other features, which make it unique when compared with other parts of the Indian Union. The district is the coldest and most elevated inhabited region in the country with altitude ranging from 2300 meters to 5000 meters. As a result of its high altitude locations, annual rainfall is extremely low. This low status of precipitation has resulted in scanty vegetation, low organic content in the soil and loose structure in the cold desert. But large-scale plantation has been going in the district since 1955 and this state of affairs is likely to change. The ancient inhabitants of Ladakh were Dards, an Indo- Aryan race. Immigrants of Tibet, Skardo and nearby parts like Purang, Guge settled in Ladakh, whose racial characters and cultures were in consonance with early settlers. Buddhism traveled from central India to Tibet via Ladakh leaving its imprint in Ladakh. Islamic missionaries also made a peaceful penetration of Islam in the early 16 th century. German Moravian Missionaries having cognizance of East India Company also made inroads towards conversion but with little success. In the 10 th century AD, Skit Lde Nemagon, the ruler of Tibet, invaded Ladakh where there was no central authority. -

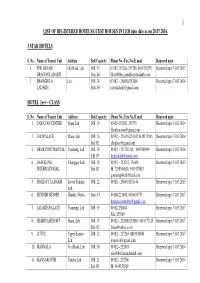

1 LIST of REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES in LEH Upto Date As on 20.07.2016

1 LIST OF REGISTERED HOTELS/GUEST HOUSES IN LEH upto date as on 20.07.2016. 3 STAR HOTELS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. THE GRAND Old Road, Leh D R. 53 01982-255266, 257786, 9419178239 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 DRAGON LADAKH Suits 06 Hotel@the granddragonladakh.com 2. SHANGRILA Leh D R. 24 01982 – 256050/253869 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 LADAKH Suits 03 [email protected] HOTEL (A+) – CLASS S. No. Name of Tourist Unit Address Bed Capacity Phone No. /Fax No./E.mail Renewed upto 1. CARAVAN CENTRE Skara Leh D R. 29 01982-252282, 253779 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 [email protected] 2. CHO PALACE Skara, Leh. D R. 26 01982 – 251659/251142,9419179565 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 Suit 02 [email protected] 3. DRUK CONTINENTAL Yourtung, Leh D R. 38 01982 – 251702, M: - 9697000999 Renewed upto 31.03.2014 S R. 03 [email protected] 4. GAWALING Changspa, Leh. D R. 18 01982 – 253252, 256456 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 INTERNATIONAL Suit 02 M. 7298540620, 9419178813 [email protected] 5. HOLIDAY LADAKH Lower Tukcha, D R. 22 01982 – 250403/251444 Renewed upto 31.03.2013 Leh. 6. HUNDER RESORT Hunder, Nubra Suits 15 01980-221048, 9469453757 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 [email protected] 7. LADAKH PALACE Yourtung, Leh D R. 19 01982-258044 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Fax. 255989 8. LHARISA RESORT Skara, Leh. D R. 15 01982 – 252000/252001, 9419177425 Renewed upto 31.03.2017 Suit 02 [email protected] 9. -

Europeans Travellers' Account on Ladakh: a Brief Analysis of The

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.11, No.3, 2020 Europeans Travellers’ Account on Ladakh: A Brief Analysis of the Socio-Economic Aspects in the 19 th Century Ansar Mehdi, Research Scholar, Panjab University. Chandigarh Abstract The regional history of Ladakh has been brought about by the historians in various aspects so far. The European travellers’ assessment about Ladakh has been interpreted in this article while emphasizing the socio-economy of the region in the 19 th century. The major historical trend in the region so far has been the ‘Aryan tribes’ residing mainly in the Dha-Hanu and Darchiks villages of Ladakh. The major European travellers who came to Ladakh in the 19 th century were Alexander Cunningham, William Moorcroft, A.H. Francke and others who left a vast account and it has been a useful source to know the region in historical sense. The economic situation of Ladakh as a country then in the mid 19 th century has been influenced by the Dogras and the British rule which had a great impact on the trade relations and several changes occurred in economical aspects of the region. Ladakh has been mostly under Buddhist monarchic rule in the early 19 th century before the Dogra invasion. This study focuses on the socio-economic changes witnessed as a result of the Dogra and British administration in Ladakh during the 19 th century specially the second half of this century. The ancient trade routes highlight the historical, economic, religious and cultural significance of the region.