Tradition the Indian Alignme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladakh Studies 31 · ESSAYS

Ladakh Studies 31 · ESSAYS {}üº²¤.JÀÛP.uÛºÛ.¾.hÔGÅ.ÇÀôz.¢ôP.±ôGÅ.qü INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES 31 July 2014 ISSN 1356-3491 i ESSAYS · Ladakh Studies 31 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES Patron: Tashi Rabgias President: John Bray, 2001, 5-2-15 Oe, Kumamoto-shi, 862-0971, Japan [email protected] EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Secretary: Sonam Wangchok Kharzong, Himalayan Cultural Heritage Foundation, P.O. Box 105, Leh-Ladakh 194 101, India. Tel: +91-94 192 18 013, [email protected] Editor: Sunetro Ghosal Stawa Neerh P.O. Box 75 JBM Road, Amboli Leh-Ladakh 194 101 Andheri West India Mumbai 400 058 India [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer and Membership Secretary: Andrea Butcher, 176 Pinhoe Road, Exeter, Devon EX4 7HH, UK, [email protected], UK Mobile/Cell: +44-78 159 06 853 Webmaster: Seb Mankelow, [email protected], Ladakh Liaison Officer & Treasurer (Ladakh): Mohammed Raza Abbasi, 112 Abbassi Enclave, Changchik, Kargil-Ladakh, 194 103, India. Email:[email protected] Mobile/Cell: +91-94 191 76 599 ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Monisha Ahmed Gulzar Hussein Munshi Mona Bhan Tashi Ldawa Sophie Day Tashi Morup Mohammed Deen Darokhan Thupstan Norboo Kaneez Fathima Bettina Zeisler Blaise Humbert-Droz Martijn van Beek Since 1974, Ladakh (made up of Leh and Kargil districts) has been readily accessible for academic study. It has become the focus of scholarship in many disciplines including the fields of anthropology, sociology, art history, Buddhist studies, history, geography, environmental studies, ecology, medicine, agricultural studies, development studies, and so forth. After the first international colloquium was organised at Konstanz in 1981, there have been biennial colloquia in many European countries and in Ladakh. -

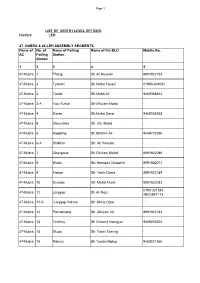

Final BLO,2012-13

Page 1 LIST OF BOOTH LEVEL OFFICER . District: LEH 47- NUBRA & 48-LEH ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS. Name of No. of Name of Polling Name of the BLO Mobile.No. AC Polling Station Station 1 3 3 4 5 47-Nubra 1 Thang Sh.Ali Hussain 8991922153 47-Nubra 2 Tyakshi Sh.Mohd Yousuf 01980-248031 47-Nubra 3 Turtuk Sh.Mohd Ali 9469368812 47-Nubra 3-A Youl Turtuk Sh:Ghulam Mohd - 47-Nubra 4 Garari Sh.Mohd Omar 9469265938 47-Nubra 5 Chulunkha Sh: Gh. Mohd - 47-Nubra 6 Bogdang Sh.Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 47-Nubra 6-A Shilkhor Sh: Ali Hassain - 47-Nubra 7 Changmar Sh.Ghulam Mehdi 8991922086 47-Nubra 8 Waris Sh: Namgail Chosphel 8991922073 47-Nubra 9 Fastan Sh: Tashi Dawa 8991922149 47-Nubra 10 Sunudo Sh: Mohd Anvar 8991922082 0190-221344 47-Nubra 11 Largyap Sh Ali Rozi /9622957173 47-Nubra 11-A Largyap Yokma Sh: Nima Otzer - 47-Nubra 12 Pachathang Sh. Ghulam Ali 8991922182 47-Nubra 13 Terchey Sh Chemet Namgyal 9469266204 47-Nubra 14 Skuru Sh; Tashi Tsering - 47-Nubra 15 Rakuru Sh Tsetan Motup 9469221366 Page 2 47-Nubra 16 Udamaru Sh:Mohd Ali 8991922151 47-Nubra 16-A Shukur Sh: Sonam Tashi - 47-Nubra 17 Hunderi Sh: Tashi Nurbu 8991922110 47-Nubra 18 Hunder Sh Ghulam Hussain 9469177470 47-Nubra 19 Hundar Dok Sh Phunchok Angchok 9469221358 47-Nubra 20 Skampuk Sh: Lobzang Thokmed - 47-Nubra 21 Partapur Smt. Sari Bano - 47-Nubra 22 Diskit Sh: Tsering Stobdan 01980-220011 47-Nubra 23 Burma Sh Tuskor Tagais 8991922100 47-Nubra 24 Charasa Sh Tsewang Stobgais 9469190201 47-Nubra 25 Kuri Sh: Padma Gurmat 9419885156 47-Nubra 26 Murgi Thukje Zangpo 9419851148 47-Nubra 27 Tongsted -

Glaciers in Xinjiang, China: Past Changes and Current Status

water Article Glaciers in Xinjiang, China: Past Changes and Current Status Puyu Wang 1,2,3,*, Zhongqin Li 1,3,4, Hongliang Li 1,2, Zhengyong Zhang 3, Liping Xu 3 and Xiaoying Yue 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Cryosphere Science/Tianshan Glaciological Station, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (X.Y.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 College of Sciences, Shihezi University, Shihezi 832000, China; [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (L.X.) 4 College of Geography and Environment Sciences, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 June 2020; Accepted: 11 August 2020; Published: 24 August 2020 Abstract: The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China is the largest arid region in Central Asia, and is heavily dependent on glacier melt in high mountains for water supplies. In this paper, glacier and climate changes in Xinjiang during the past decades were comprehensively discussed based on glacier inventory data, individual monitored glacier observations, recent publications, as well as meteorological records. The results show that glaciers have been in continuous mass loss and dimensional shrinkage since the 1960s, although there are spatial differences between mountains and sub-regions, and the significant temperature increase is the dominant controlling factor of glacier change. The mass loss of monitored glaciers in the Tien Shan has accelerated since the late 1990s, but has a slight slowing after 2010. Remote sensing results also show a more negative mass balance in the 2000s and mass loss slowing in the latest decade (2010s) in most regions. -

1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh Kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs Editorial 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL protests. Later they also constructed a road from Lanak La to Kongka Pass. In the north, they had built another road, west of the Aksai Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 in Eastern Ladakh was fought in the area Chin Highway, from the Northern border to Qizil Jilga, Sumdo, between Karakoram Pass in the North to Demchok in the South East. Samzungling and Kongka Pass. The area under territorial dispute at that time was only the Aksai Chin plateau in the north east corner of Ladakh through which the Chinese In the period between 1960 and October 1962, as tension increased had constructed Western Highway linking Xinjiang Province to Lhasa. on the border, the Chinese inducted fresh troops in occupied Ladakh. The Chinese aim of initially claiming territory right upto the line – Unconfirmed reports also spoke of the presence of some tanks in Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) – Track Junction and thereafter capturing it general area of Rudok. The Chinese during this period also improved in October 1962 War was to provide depth to the Western Highway. their road communications further and even the posts opposite DBO were connected by road. The Chinese also had ample animal In Galwan – Chang Chenmo Sector, the Chinese claim line was transport based on local yaks and mules for maintenance. The horses cleverly drawn to include passes and crest line so that they have were primarily for reconnaissance parties. -

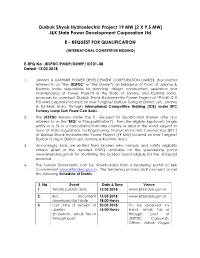

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd. E - REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATION (INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING) E-RFQ No: JKSPDC/PMDP/DSHEP/10101-08 Dated: 13.03.2018 1. JAMMU & KASHMIR POWER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, (hereinafter referred to as “the JKSPDC" or "the Owner”) an Enterprise of Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir, India, responsible for planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of Power Projects in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, India, proposes to construct Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project of 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) capacity located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India, through International Competitive Bidding (ICB) under EPC Turnkey Lump Sum Fixed Cost Basis. 2. The JKSPDC hereby invites the E - Request for Qualification (herein after also referred to as the "RFQ" or "Prequalification") from the eligible Applicants (single entity or a JV or a consortium) from any country or area in the world subject to Govt of India regulations, for Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) of Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project (19 MW) located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India. 3. Accordingly, bids are invited from bidders who comply and satisfy eligibility criteria given in the detailed E-RFQ available on the e-tendering portal www.jktenders.gov.in for shortlisting the bidders found eligible for the aforesaid proposal. 4. The Tender Documents can be downloaded from e-tendering portal of J&K Government www.jktenders.gov.in . The tendering process shall proceed as per the following Schedule of Events: S. -

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 14 Points of Jinnah (March 9, 1929) Phase “II” of CDM

General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 1 www.teachersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | Adda247 App General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Contents General Awareness Capsule for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................ 3 Indian Polity for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 3 Indian Economy for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ........................................................................................... 22 Geography for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .................................................................................................. 23 Ancient History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 41 Medieval History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .......................................................................................... 48 Modern History for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ............................................................................................ 58 Physics for AFCAT II 2021 Exam .........................................................................................................73 Chemistry for AFCAT II 2021 Exam.................................................................................................... 91 Biology for AFCAT II 2021 Exam ....................................................................................................... 98 Static GK for IAF AFCAT II 2021 ...................................................................................................... -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

Nuclear Capability, Bargaining Power, and Conflict by Thomas M. Lafleur

Nuclear capability, bargaining power, and conflict by Thomas M. LaFleur B.A., University of Washington, 1992 M.A., University of Washington, 2003 M.M.A.S., United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2004 M.M.A.S., United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2005 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract Traditionally, nuclear weapons status enjoyed by nuclear powers was assumed to provide a clear advantage during crisis. However, state-level nuclear capability has previously only included nuclear weapons, limiting this application to a handful of states. Current scholarship lacks a detailed examination of state-level nuclear capability to determine if greater nuclear capabilities lead to conflict success. Ignoring other nuclear capabilities that a state may possess, capabilities that could lead to nuclear weapons development, fails to account for the potential to develop nuclear weapons in the event of bargaining failure and war. In other words, I argue that nuclear capability is more than the possession of nuclear weapons, and that other nuclear technologies such as research and development and nuclear power production must be incorporated in empirical measures of state-level nuclear capabilities. I hypothesize that states with greater nuclear capability hold additional bargaining power in international crises and argue that empirical tests of the effectiveness of nuclear power on crisis bargaining must account for all state-level nuclear capabilities. This study introduces the Nuclear Capabilities Index (NCI), a six-component scale that denotes nuclear capability at the state level. -

Glaciers in Pakistan | World General Knowledge

Glaciers in Pakistan | World General Knowledge With 7,253 known glaciers, including 543 in the Chitral Valley, there is more glacial ice in Pakistan than anywhere on Earth outside the polar regions, according to various studies. Those glaciers feed rivers that account for about 75 percent of the stored-water supply in the country of at least 200 million. But as in many other parts of the world, researchers say, Pakistan’s glaciers are receding, especially those at lower elevations, including here in the Hindu Kush mountain range in northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Among the causes cited by scientists: diminished snowfall, higher temperatures, heavier summer rainstorms and rampant deforestation. 1) Baltoro Glacier The glacier at 63km in length is one of the largest land glaciers on Earth. It can be accessed through Gilgit-Baltistan region. The glacier gives rise to the Shigar River. 2) Batura Glacier At 53 km in length, the Batura Glacier is up there with the biggest in the world. It lies in the Batura Valley in the Gojal region of Gilgit Baltistan. 3) Biafo Glacier The Biago Glacier is 67kms long and the third biggest land glacier in the entire world. Mango, Baintha and Namla are campsites set up near the glacier and can be accessed through the Askole Village of Gilgit-Baltistan. 4) Panmah Glacier Located in the Central Karakoram National Park, Gilgit-Baltistan, 5) Rupal Glacier It is the source of the Rupal River and lies in the Great Himalayas. It is South of the Nanga Parbat and North of Laila Peak. Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 Glaciers in Pakistan | World General Knowledge 6) Sarpo Laggo The glacier flows from Pakistan to China just north of the Baltoro Muztagh Range. -

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ Laurianne Bruneau & John Vincent Bellezza I. An introduction to the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh his paper examines common thematic and esthetic features discernable in the rock art of the western portion of the T Tibetan plateau.1 This rock art is international in scope; it includes Ladakh (La-dwags, under Indian jurisdiction), Tö (Stod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang, under Chinese administration) hereinafter called Upper Tibet. This highland rock art tradition extends between 77° and 88° east longitude, north of the Himalayan range and south of the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains. [Fig.I.1] This work sets out the relationship of this art to other regions of Inner Asia and defines what we call the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’. The primary materials for this paper are petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings). They comprise one of the most prolific archaeological resources on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Although pictographs are quite well distributed in Upper 1 Bellezza would like to heartily thank Joseph Optiker (Burglen), the sole sponsor of the UTRAE I (2010) and 2012 rock art missions, as well as being the principal sponsor of the UTRAE II (2011) expedition. He would also like to thank David Pritzker (Oxford) and Lishu Shengyal Tenzin Gyaltsen (Gyalrong Trokyab Tshoteng Gön) for their generous help in completing the UTRAE II. Sponsors of earlier Bellezza expeditions to survey rock art in Upper Tibet include the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) and the Asian Cultural Council (New York). -

Economic Review” of District Leh, for the Year 2014-15

PREFACE The District Statistics and Evaluation Agency Leh under the patronage of Directorate of Economic and Statistics (Planning and Development Department) is bringing out annual publication titled “Economic Review” of District Leh, for the year 2014-15. The publication 22st in the series, presents the progress achieved in various socio-economic facts of the district economy. I hope that the publication will be a useful tool in the hands of planners, administrators, Policy makers, academicians and other users and will go a long way in helping them in their respective pursuit. Suggestions to improve the publication in terms of coverage, quality etc. in the future issue of the publication will be appreciated Tashi Tundup District statistics and Evaluation Officer Leh CONTENTS Page No. District Profile 1-6 Agriculture and Allied Activities • Agriculture 7-9 • Horticulture 10 • Animal Husbandry 11-13 • Sheep Husbandry 14-15 • Forest 16 • Soil Conservation 17 • Cooperative 17-18 • Irrigation 19 Industries and Employment • Industries 19-20 • Employment & Counseling Centre 20 • Handicraft/Handloom 21 Economic Infrastructure • Power 21-22 • Tourism 22-23 • Financial institution 24-25 • Transport and communication 24-27 • Information Technology 27-28 Social Sector • Housing 29 • Education 29-31 • Health 31-33 • Water Supply and Rural Sanitation 33 • Women and Child Development 34-36 1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe.