Towards a Comprehensive Documentation and Use of Pistacia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlight: Chinese Pistache (Pistacia Chinensis)

Fall 2019 Finally Fall! Planting and Pruning Time! If you are done with the heat of summer, fall is just around the corner. Cooler temperatures offer a great opportunity to gardeners. Fall is the best season to plant trees around your landscape, and it is the best season for vegetable gardens in El Paso. Why? Our fall temperatures are warm with little chance of frost, and we still have many sunshine hours to help vegetables grow. Fall is also the best time to start cleaning up the yard. Once trees lose their leaves, it is the best time to prune. Let us look at some fall tips for the yard to get ready for winter and to save water. Spotlight: Chinese Pistache (Pistacia chinensis) A great double duty tree for El Paso is the Chinese Pistache, this deciduous tree not only provides most needed shade in the summer, but it pops with striking fall color ranging from red to orange in the fall. Description Deciduous tree with rounded crown 40' x 35' Photo courtesy: elpasodesertblooms.org. Leaves have 10-16 leaflets Striking fall coloring arrives in shades of reds and orange Dense shade tree Red fruit on female trees Native to China and the Philippines Don't miss the latest conservation tips from EPWater and events taking place at the TecH 2 O Learning Center ! Click the button below to subscribe to Conservation Currents. Subscribe Share this email: Manage your preferences | Opt out using TrueRemove® Got this as a forward? Sign up to receive our future emails. View this email online . -

Analysis of Atmospheric Pollen Grains in Dursunbey (Balikesir), Turkey

http://dergipark.gov.tr/trkjnat Trakya University Journal of Natural Sciences, 19(2): 137-146, 2018 ISSN 2147-0294, e-ISSN 2528-9691 Research Article DOI: 10.23902/trkjnat.402912 ANALYSIS OF ATMOSPHERIC POLLEN GRAINS IN DURSUNBEY (BALIKESİR), TURKEY Hanife AKYALÇIN1, Aycan TOSUNOĞLU2*, Adem BIÇAKÇI2 1 18 Mart University, Faculty of Science & Arts, Department of Biology, Çanakkale, TURKEY 2 Uludağ University, Faculty of Science & Arts, Department of Biology, Bursa, TURKEY ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2303-672X *Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] Cite this article as: Akyalçın H., Tosunoğlu A. & Bıçakçı A. 2018. Analysis of Atmospheric Pollen Grains in Dursunbey (Balıkesir), Turkey. Trakya Univ J Nat Sci, 19(2): 137-146, DOI: 10.23902/trkjnat.402912 Received: 07 March 2018, Accepted: 03 September 2018, Online First: 11 September 2018, Published: 15 October 2018 Abstract: In this study, airborne pollen grains in the atmosphere of Dursunbey (Balıkesir, Turkey) were collected using a gravimetric method. The pollen grains were investigated by light microscopy and a total of 6265 pollen grains per cm2 were counted. 42 different pollen types were identified of which 24 belonged to the arboreal plants (86.17% of the annual pollen index) and 18 to non-arboreal plants (13.16% of the annual pollen index). A small portion of the pollens (42 grains, 0.67%) were not identified. The most frequent pollen types, which constituted more than 1% of annual pollen count were regarded as the predominating pollen types for the region. The predominating group was determined to be consisted of pollens of Pinus L. -

What Is a Tree in the Mediterranean Basin Hotspot? a Critical Analysis

Médail et al. Forest Ecosystems (2019) 6:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0170-6 RESEARCH Open Access What is a tree in the Mediterranean Basin hotspot? A critical analysis Frédéric Médail1* , Anne-Christine Monnet1, Daniel Pavon1, Toni Nikolic2, Panayotis Dimopoulos3, Gianluigi Bacchetta4, Juan Arroyo5, Zoltán Barina6, Marwan Cheikh Albassatneh7, Gianniantonio Domina8, Bruno Fady9, Vlado Matevski10, Stephen Mifsud11 and Agathe Leriche1 Abstract Background: Tree species represent 20% of the vascular plant species worldwide and they play a crucial role in the global functioning of the biosphere. The Mediterranean Basin is one of the 36 world biodiversity hotspots, and it is estimated that forests covered 82% of the landscape before the first human impacts, thousands of years ago. However, the spatial distribution of the Mediterranean biodiversity is still imperfectly known, and a focus on tree species constitutes a key issue for understanding forest functioning and develop conservation strategies. Methods: We provide the first comprehensive checklist of all native tree taxa (species and subspecies) present in the Mediterranean-European region (from Portugal to Cyprus). We identified some cases of woody species difficult to categorize as trees that we further called “cryptic trees”. We collected the occurrences of tree taxa by “administrative regions”, i.e. country or large island, and by biogeographical provinces. We studied the species-area relationship, and evaluated the conservation issues for threatened taxa following IUCN criteria. Results: We identified 245 tree taxa that included 210 species and 35 subspecies, belonging to 33 families and 64 genera. It included 46 endemic tree taxa (30 species and 16 subspecies), mainly distributed within a single biogeographical unit. -

Review Article Five Pistacia Species (P. Vera, P. Atlantica, P. Terebinthus, P

Hindawi Publishing Corporation The Scientific World Journal Volume 2013, Article ID 219815, 33 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/219815 Review Article Five Pistacia species (P. vera, P. atlantica, P. terebinthus, P. khinjuk,andP. lentiscus): A Review of Their Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology Mahbubeh Bozorgi,1 Zahra Memariani,1 Masumeh Mobli,1 Mohammad Hossein Salehi Surmaghi,1,2 Mohammad Reza Shams-Ardekani,1,2 and Roja Rahimi1 1 Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Faculty of Traditional Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417653761, Iran 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran Correspondence should be addressed to Roja Rahimi; [email protected] Received 1 August 2013; Accepted 21 August 2013 Academic Editors: U. Feller and T. Hatano Copyright © 2013 Mahbubeh Bozorgi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Pistacia, a genus of flowering plants from the family Anacardiaceae, contains about twenty species, among them five are more popular including P. vera, P. atlantica, P. terebinthus, P. khinjuk, and P. l e nti s c u s . Different parts of these species have been used in traditional medicine for various purposes like tonic, aphrodisiac, antiseptic, antihypertensive and management of dental, gastrointestinal, liver, urinary tract, and respiratory tract disorders. Scientific findings also revealed the wide pharmacological activities from various parts of these species, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral, anticholinesterase, anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, antidiabetic, antitumor, antihyperlipidemic, antiatherosclerotic, and hepatoprotective activities and also their beneficial effects in gastrointestinal disorders. -

Small Mammal Mail

Small Mammal Mail Newsletter celebrating the most useful yet most neglected Mammals for CCINSA & RISCINSA -- Chiroptera, Rodent, Insectivore, & Scandens Conservation and Information Networks of South Asia Volume 2 Number 2 ISSN 2230-7087 January 2011 Contents First report of Hipposideros lankadiva (Chiroptera: Second Record of Hipposideros fulvus in Nepal, Hipposideridae) from Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, Narayan Lamichhane and Rameshwor Ghimire, India, Harpreet Kaur, P. Venkateshwarlu, C. Srinivasulu Pp. 27-28 and Bhargavi Srinivasulu, Pp. 2-3 Published! Bats of Nepal- A Field Guide, Compiled and First report of Taphozous nudiventris (Chiroptera: edited by: Pushpa R. Acharya, Hari Adhikari, Sagar Emballonuridae) from Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, Dahal, Arjun Thapa and Sanjan Thapa, P. 29 India, P. Venkateshwarlu, C. Srinivasulu, Bhargavi Srinivasulu, and Harpreet Kaur, Pp. 4-5 The diet of Indian flying-foxes (Pteropus giganteus) in urban habitats of Pakistan, Muhammad Mahmood-ul- Skull cum Baculum Morphology and PCR Approach in Hassan, Tayiba L. Gulraiz, Shahnaz A. Rana and Arshad Identification of Pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Javid, Pp. 30-36 Vespertilionidae) from Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Sunsari, Nepal, Sanjan Thapa and Nanda Bahadur First phase study of Bats in Far-western Development Singh, P. 5 Region Nepal, Prasant Chaudhary and Rameshwor Ghimire, Pp. 37-39 Additional site records of Indian Giant Squirrel Ratufa indica (Erxleben, 1777) (Mammalia: Rodentia) in Announcement: Bat CAMP 2011, January 22-30, Godavari River Basin, Andhra Pradesh, India, M. Monfort Conservation Park (MCPARK) Seetharamaraju, C. Srinivasulu and Bhargavi Island Garden City of Samal, Pp. 40-42 Srinivasulu, Pp. 6-7 A note on road killing of Indian Pangolin Manis crassicaudata Gray at Kambalakonda Wildlife Sanctuary of Eastern Ghat ranges, Murthy K.L.N. -

Weed Risk Assessment for Pistacia Chinensis Bunge (Anacardiaceae)

Weed Risk Assessment for Pistacia United States chinensis Bunge (Anacardiaceae) – Department of Agriculture Chinese pistache Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service November 27, 2012 Version 1 Pistacia chinensis (source: D. Boufford, efloras.com) Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Pistacia chinensis Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is defined as “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA)—specifically, the PPQ WRA model (Koop et al., 2012)—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because the PPQ WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or for any area within it. As part of this analysis, we use a stochastic simulation to evaluate how much the uncertainty associated with the analysis affects the model outcomes. -

Non-Wood Forest Products from Conifers

Page 1 of 8 NON -WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 12 Non-Wood Forest Products From Conifers FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-37 ISBN 92-5-104212-8 (c) FAO 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 - AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONIFERS WHAT ARE CONIFERS? DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE USES CHAPTER 2 - CONIFERS IN HUMAN CULTURE FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY RELIGION POLITICAL SYMBOLS ART CHAPTER 3 - WHOLE TREES LANDSCAPE AND ORNAMENTAL TREES Page 2 of 8 Historical aspects Benefits Species Uses Foliage effect Specimen and character trees Shelter, screening and backcloth plantings Hedges CHRISTMAS TREES Historical aspects Species Abies spp Picea spp Pinus spp Pseudotsuga menziesii Other species Production and trade BONSAI Historical aspects Bonsai as an art form Bonsai cultivation Species Current status TOPIARY CONIFERS AS HOUSE PLANTS CHAPTER 4 - FOLIAGE EVERGREEN BOUGHS Uses Species Harvesting, management and trade PINE NEEDLES Mulch Decorative baskets OTHER USES OF CONIFER FOLIAGE CHAPTER 5 - BARK AND ROOTS TRADITIONAL USES Inner bark as food Medicinal uses Natural dyes Other uses TAXOL Description and uses Harvesting methods Alternative -

Cytotoxic Activity of Extracts/Fractions of Various Parts of Pistacia

nal atio Me sl d n ic a in r e Uddin et al., Transl Med 2013, 3:2 T Translational Medicine DOI: 10.4172/2161-1025.1000118 ISSN: 2161-1025 Research Article Open Access Cytotoxic Activity of Extracts/Fractions of Various Parts of Pistacia Integerrima Stewart Ghias Uddin1*, Abdur Rauf1, Bina Shaheen Siddiqui2 and Haroon Khan3 1Institute of Chemical Sciences, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 2H.E.J. Research Institute of Chemistry, International Center for Chemical and Biological Sciences, University of Karachi, Pakistan 3Gandhara College of Pharmacy, Gandhara University, Peshawar, Pakistan Abstract The aim of present study was to scrutinize cytotoxic activity of extracts/fractions of various parts of Pistacia integerrima Stewart in an established in-vitro brine shrimp cytotoxic assay. The extracts/fractions of different parts of the plant demonstrated profound cytotoxic effect against Artemia salina (Leach) shrimp larvae. Of the various parts of plant tested, galls accumulated most cytotoxic agents. Among the tested extracts/fractions, hexane was least cytotoxic and therefore indicated more polar nature of cytotoxic constituents. In conclusions, extracts/fractions of various parts of P. integerrima exhibited marked cytotoxic profile of more polar nature. Keywords: Pistacia integerrim; Extracts/fractions of different parts; Dir), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan in the month of February, 2010. Brine shrimp cytotoxic assay The identification of plant material was done by Dr. Abdur Rashid plant taxonomist Department of Botany, University of Peshawar. A voucher Introduction specimen no (RF-895) was deposited in the herbarium of the same Pistacia integerrima (J. L. Stewart ex Brandis) belongs to family institution. anacardiacea. It mostly grows at a height of 12000 to 8000 feet in Extraction and fractionation Eastern Himalayan regions [1]. -

Phytosociological Analysis of Pine Forest at Indus Kohistan, Kpk, Pakistan

Pak. J. Bot., 48(2): 575-580, 2016. PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF PINE FOREST AT INDUS KOHISTAN, KPK, PAKISTAN ADAM KHAN1, MOINUDDIN AHMED2, MUHAMMAD FAHEEM SIDDIQUI*3, JAVED IQBAL1 AND MUHAMMAD WAHAB4 1Laboratory of plant ecology and Dendrochronology, Department of Botany, Federal Urdu University, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Campus Karachi, Pakistan 2Department of Earth and Environmental Systems, 600 Chestnut Street Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN, USA 3Department of Botany, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan 4Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract The study was carried out to describe the pine communities at Indus Kohistan valley in quantitative term. Thirty stands of relatively undisturbed vegetation were selected for sampling. Quantitative sampling was carried out by Point Centered Quarter (PCQ) method. Seven tree species were common in the Indus Kohistan valley. Cedrus deodara was recorded from twenty eight different locations and exhibited the highest mean importance value while Pinus wallichiana was recorded from 23 different locations and exhibited second highest mean importance value. Third most occurring species was Abies pindrow that attained the third highest mean importance value and Picea smithiana was recorded from eight different locations and attained fourth highest importance value while it was first dominant in one stand and second dominant in four stands. Pinus gerardiana, Quercus baloot and Taxus fuana were the rare species in this area, these species attained low mean importance value. Six communities and four monospecific stands of Cedrus deodara were recognized. Cedrus-Pinus community was the most occurring community, which was recorded from 13 different stands. -

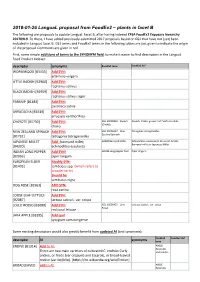

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Biodiversity Conservation in Botanical Gardens

AgroSMART 2019 International scientific and practical conference ``AgroSMART - Smart solutions for agriculture'' Volume 2019 Conference Paper Biodiversity Conservation in Botanical Gardens: The Collection of Pinaceae Representatives in the Greenhouses of Peter the Great Botanical Garden (BIN RAN) E M Arnautova and M A Yaroslavceva Department of Botanical garden, BIN RAN, Saint-Petersburg, Russia Abstract The work researches the role of botanical gardens in biodiversity conservation. It cites the total number of rare and endangered plants in the greenhouse collection of Peter the Great Botanical garden (BIN RAN). The greenhouse collection of Pinaceae representatives has been analysed, provided with a short description of family, genus and certain species, presented in the collection. The article highlights the importance of Pinaceae for various industries, decorative value of plants of this group, the worth of the pinaceous as having environment-improving properties. In Corresponding Author: the greenhouses there are 37 species of Pinaceae, of 7 geni, all species have a E M Arnautova conservation status: CR -- 2 species, EN -- 3 species, VU- 3 species, NT -- 4 species, LC [email protected] -- 25 species. For most species it is indicated what causes depletion. Most often it is Received: 25 October 2019 the destruction of natural habitats, uncontrolled clearance, insect invasion and diseases. Accepted: 15 November 2019 Published: 25 November 2019 Keywords: biodiversity, botanical gardens, collections of tropical and subtropical plants, Pinaceae plants, conservation status Publishing services provided by Knowledge E E M Arnautova and M A Yaroslavceva. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons 1. Introduction Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and Nowadays research of biodiversity is believed to be one of the overarching goals for redistribution provided that the original author and source are the modern world. -

Characterization of the Wild Trees and Shrubs in the Egyptian Flora

10 Egypt. J. Bot. Vol. 60, No. 1, pp. 147-168 (2020) Egyptian Journal of Botany http://ejbo.journals.ekb.eg/ Characterization of the Wild Trees and Shrubs in the Egyptian Flora Heba Bedair#, Kamal Shaltout, Dalia Ahmed, Ahmed Sharaf El-Din, Ragab El- Fahhar Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, 31527, Tanta, Egypt. HE present study aims to study the floristic characteristics of the native trees and shrubs T(with height ≥50cm) in the Egyptian flora. The floristic characteristics include taxonomic diversity, life and sex forms, flowering activity, dispersal types,economic potential, threats and national and global floristic distributions. Nine field visits were conducted to many locations all over Egypt for collecting trees and shrubs. From each location, plant and seed specimens were collected from different habitats. In present study 228 taxa belonged to 126 genera and 45 families were recorded, including 2 endemics (Rosa arabica and Origanum syriacum subsp. sinaicum) and 5 near-endemics. They inhabit 14 habitats (8 natural and 6 anthropogenic). Phanerophytes (120 plants) are the most represented life form, followed by chamaephytes (100 plants). Bisexuals are the most represented. Sarcochores (74 taxa) are the most represented dispersal type, followed by ballochores (40 taxa). April (151 taxa) and March (149 taxa) have the maximum flowering plants. Small geographic range - narrow habitat - non abundant plants are the most represented rarity form (180 plants). Deserts are the most rich regions with trees and shrubs (127 taxa), while Sudano-Zambezian (107 taxa) and Saharo-Arabian (98 taxa) was the most. Medicinal plants (154 taxa) are the most represented good, while salinity tolerance (105 taxa) was the most represented service and over-collecting and over-cutting was the most represented threat.