Al-Shabaab and Violence in Kenya by David M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Resilience to Violent Extremism in Kenya

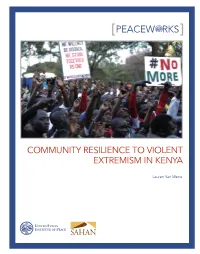

[PEACEW RKS [ COMMUNITY RESILIENCE TO VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN KENYA Lauren Van Metre ABOUT THE REPORT Focusing on six urban neighborhoods in Kenya, this report explores how key resilience factors have prevented or countered violent extremist activity at the local level. It is based on a one-year, mixed-method study led by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and supported by Sahan Research. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Lauren Van Metre, PhD, led the Applied Research Center at USIP and currently conducts research and writing on community resilience to violence in Ukraine and Kenya. She directed USIP’s grant programs, working with researchers worldwide to build evidence for successful interventions against electoral and extremist violence. Cover photo: People carry placards as they attend a memorial concert for the Garissa University students who were killed during an attack by gunmen, at the “Freedom Corner” in Nairobi, Kenya on April 14, 2015. Kenya gave the United Nations three months to remove Dadaab camp, housing 350,000 registered Somali refugees, as part of its response to the killing of 148 people in nearby Garissa by a Somali Islamist group. Reuters/Thomas Mukoya Image ID: rtr4xbqv. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 122. First published 2016. ISBN: 978-1-60127-615-5 © 2016 by the United States Institute of Peace CONTENTS PEACEWORKS • SEPTEMBER 2016 • NO. -

Assessing the Vulnerability of Kenyan Youths to Radicalisation and Extremism

Institute for Security Studies PAPER Assessing the vulnerability of Kenyan youths to radicalisation and extremism INTRODUCTION country is also central to the region and thus deserves That there is an emerging trend of religious radicalisation in closer scrutiny. Although Kenya’s intervention in Somalia East Africa is not in doubt. Somalia, which has experienced served to incite a terrorist response, the experience of various forms of conflict since 1991, has often been seen Uganda, Ethiopia and Burundi, all of which have had troops as the source of extremism in the region, especially in Somalia since 2006, showed different trends. Only the following the attacks on the United States (US) embassies attacks in Uganda and Kenya were attributed to those in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi on 7 August 1998. Yet closer countries’ interventions in Somalia. And, despite the fact investigation reveals that Somali nationals were not behind that those directly involved in these attacks were Ugandan most of the incidents outside Somalia’s borders. Somalia nationals, Kenyans and Tanzanians helped plan and provides a safe haven, training camps and opportunities for execute the attacks, not members of traditional extremists to fight the ‘enemies of Islam’, but al-Qaeda and Somali communities. later al-Shabaab have executed attacks in the region by This is not to say that individuals within the traditional relying on local assistance and support. At the same time, Muslim community have not used frustrations and al-Shabaab managed to recruit Kenyan, Ugandan and vulnerabilities among the youth – Muslim and non-Muslim Tanzanian nationals to its ranks in Somalia. -

The Prospects of Islamism in Kenya As Epitomized by Sheikh Aboud Rogo’S Sermons

Struggle against Secular Power: The Prospects of Islamism in Kenya as Epitomized by Sheikh Aboud Rogo’s Sermons (Hassan Juma Ndzovu, Freie University Berlin) Abstract Kenya is witnessing a pronounced Muslim activism presence in the country’s public sphere. The Muslims activism prominence in the public space could be attributed to numerous factors, but significantly to political liberalization of the early 1990s. Due to the democratic freedom, it encouraged the emergence of a section of Muslim clerics advocating for Islam as an alternative political ideology relevant to both the minority Muslims and the general Kenya’s population. This group of Muslim clerics espouses Islamist view of the world, and like other Islamists in the world, their key call is the insistence of the establishment of an Islamic state governed by sharia, which they regard to be the solution to all problems facing the humanity. The article seeks to contribute to the larger debate on Islamism within the Kenyan context. Though some commentators are pessimistic of the presence of Islamism in Kenya, I endeavor to demonstrate its existence in the country. In this article, I conceptualize Islamism in Kenya in the form of individual Muslim clerics who reject secularism, democracy and the nation-state. In this respect, I employ Sheikh Aboud Rogo’s sermons, comments and statements as a representation of Islamism in Kenya. Through his hateful and inciting orations that included issuing fatwas (legal opinions) against the government, praising attacks on churches as appropriate and acceptable in Islam, and completely disregarding mutual religious co-existence, indicated the existence of an extreme form of Islamism among sections of Muslims in Kenya. -

Al-Qaeda –Mombassa Attacks 28 November 2002 by Jonathan Fighel1

The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center June 16, 2011 Al-Qaeda –Mombassa Attacks 28 November 2002 By Jonathan Fighel1 On June 11, 2011 Somali police reported that Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, one of Africa's most wanted al-Qaeda operatives, was killed in the capital of the Horn of Africa. Mohammed was reputed to be the head of al-Qaeda in east Africa, operated in Somalia and is accused of playing a lead role in the 1998 embassy attacks in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, which killed 240 people. Mohammed is also believed to have masterminded the suicide attack on an Israeli-owned hotel in Mombassa, Kenya in November 2002 that killed 15 people, including three Israeli tourists. Introduction On the morning of November 28, 2002, Al-Qaeda launched coordinated attacks in Mombassa, Kenya against the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel and an Israeli passenger jet.2 The near simultaneous attacks involved Al-Qaeda operatives supported by a local infrastructure. In the first attack, the terrorists fired two SA-7 surface-to-air missiles at a departing Israeli Arkia charter Boeing 757 passenger aircraft, carrying 261 passengers and crew, both missiles missed. The second occurred twenty minutes later, when an explosives- laden vehicle driven by two suicide attackers, blew up in front of the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel. The attack was timed just as the hotel’s Israeli guests arrived—having traveled aboard the same Arkia plane that had embarked on the return flight to Israel. As a result of the 1 The author is a senior researcher scholar at The International Institute for Counter Terrorism -Herzliya -Israel (ICT).First published on ICT web site http://www.ict.org.il/Articles/tabid/66/Articlsid/942/currentpage/1/Default.aspx 2 CNN, “Israeli Report Links Kenya Terrorist to Al Qaeda” , 29 November 2002. -

A Critique of Police Oversight Mechanisms in Kenya with Regard to Extrajudicial Killings

A CRITIQUE OF POLICE OVERSIGHT MECHANISMS IN KENYA WITH REGARD TO EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Laws Degree, Strathmore University Law School By JOY WANJIKU NJOROGE 083919 Prepared under the supervision of MS JERUSHA ASIN OWINO JANUARY 2018 Word count (13, 395) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................................................................................................................... iv DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................. vii LIST OF LEGAL INSTRUMENTS ................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Statement of Problem ............................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Justification of the Study ....................................................................................................... -

Islam, Politics, and Violence on the Kenya Coast Justin Willis, Hassan Mwakimako

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Islam, Politics, and Violence on the Kenya Coast Justin Willis, Hassan Mwakimako To cite this version: Justin Willis, Hassan Mwakimako. Islam, Politics, and Violence on the Kenya Coast. [Research Report] 4, Sciences Po Bordeaux; IFRA - Nairobi, Kenya; Observatoire des Enjeux Politiques et Sécuritaires dans la Corne de l’Afrique - Les Afriques dans le monde / Sciences po Bordeaux. 2014. halshs-02465228 HAL Id: halshs-02465228 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02465228 Submitted on 3 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Observatoire des Enjeux Politiques et Sécuritaires dans la Corne de l’Afrique Hassan MWAKIMAKO & Justin WILLIS Hassan Mwakimako is Associate Professor of Islamic Studies at Pwani University, Kenya. His research interest is on the interface between Islam and its relations with the State in colonial and post-colonial sub-Saharan Africa. Justin Willis is Professor in History at Durham University in the UK. He has been involved in research on the modern history of the Kenya coast since the 1980s. -

Containment Or Contagion? Countering Al Shabaab Efforts to Sow Discord in Kenya

STUDIES IN AFRICAN SECURITY Containment or Contagion? Countering al Shabaab Efforts to Sow Discord in Kenya Daniel Torbjörnsson and Michael Jonsson Since the al Shabaab attacks on the Westgate Mall in 2013 and the massacre at a university in Garissa in 2015, attempts by the terrorist group to expand operations and recruitment in Kenya have been a growing source of concern. The Kenyan state has taken several measures to counter violent extremism, including giving muslim-dominated regions increasing autonomy and issuing an amnesty for Kenyan al Shabaab returnees in 2015. Even so, broad and heavy- handed police sweeps, forced disappearances and killings of radical clerics have been exploited by al Shabaab in radicalisation and recruitment efforts. This carries the risk of polarizing inter-ethnic and inter-faith relations in Kenya and could threaten the future stability of the country. A decade after its emergence, al Shabaab is, according to prominent analyst Matthew Bryden, “on the threshold of becoming a genuinely transnational organization”. While the terrorist threat posed by al Shabaab outside Somalia has been felt in the entire region – the group has conducted terrorist attacks in Uganda, Djibouti and Ethiopia – it has been most acute in Kenya. Besides the Westgate and Garissa attacks, in which more than 200 people were killed, there have been several ruthless attacks in Kenya’s northeastern provinces, along the coast and in the capital, Nairobi. In its bid to sow discord, al Shabaab has undermined policies intended to benefit Kenya’s Muslim minority. The terrorist threat in Kenya In 2011 Kenya decided to intervene militarily in Somalia to aid the Somali government in fighting al Shabaab and contain the terrorism problem.1 However, the initial effect was contagion, with increasing terrorist attacks from al Shabaab inside Kenya. -

ISS Paper 245 Kenya Youth.Indd

Institute for Security Studies PAPER Assessing the vulnerability of Kenyan youths to radicalisation and extremism INTRODUCTION country is also central to the region and thus deserves That there is an emerging trend of religious radicalisation in closer scrutiny. Although Kenya’s intervention in Somalia East Africa is not in doubt. Somalia, which has experienced served to incite a terrorist response, the experience of various forms of conflict since 1991, has often been seen Uganda, Ethiopia and Burundi, all of which have had troops as the source of extremism in the region, especially in Somalia since 2006, showed different trends. Only the following the attacks on the United States (US) embassies attacks in Uganda and Kenya were attributed to those in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi on 7 August 1998. Yet closer countries’ interventions in Somalia. And, despite the fact investigation reveals that Somali nationals were not behind that those directly involved in these attacks were Ugandan most of the incidents outside Somalia’s borders. Somalia nationals, Kenyans and Tanzanians helped plan and provides a safe haven, training camps and opportunities for execute the attacks, not members of traditional extremists to fight the ‘enemies of Islam’, but al-Qaeda and Somali communities. later al-Shabaab have executed attacks in the region by This is not to say that individuals within the traditional relying on local assistance and support. At the same time, Muslim community have not used frustrations and al-Shabaab managed to recruit Kenyan, Ugandan and vulnerabilities among the youth – Muslim and non-Muslim Tanzanian nationals to its ranks in Somalia. -

Is the Rise of Terrorism Activities Leading to the Extrajudicial Killings in Kenya?

International Journal of Arts and Humanities Vol. 1 No. 3; October 2015 Is the Rise of Terrorism Activities Leading to the Extrajudicial Killings in Kenya? Jack Gordon Osamba Graduate Student- Masters in Liberal Studies Southern Methodist University (S.M.U) United States of America Abstract An Independent Study on how Kenya government is using Anti-Terrorism Police Unit (ATPU) to carry out Extrajudicial Killings. The Issue of enforced disappearances and killings in the fight of Al-Shabaab terror group. The implications of the presence of Kenya Defense Forces in Somalia and government’s predicament to get out. The Issue of Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya hosting Somalia Refugees and others. Human Rights Violations in the fight of Terrorism. Introduction The encyclopedia defines extrajudicial killing as the killing of a person by governmental authorities without the sanction of any judicial proceeding or legal process. Extrajudicial punishments are mostly seen by humanity to be unethical, since they bypass the due process of the legal jurisdiction in which they occur. Extrajudicial killings often target leading political, trade union, dissident, religious, and social figures and may be carried out by the state government or other state authorities like the armed forces or police.i According to a National Commission on Human Rights 2008 report: "Extrajudicial executions and other brutal acts of extreme cruelty have been perpetrated by the police against so-called Mungiki adherents and that these acts may have been committed pursuant to official policy sanctioned by the political leadership, the police commissioner and top police commander". HRW observed in 2008 that, "The brutality of the police crackdown matched or even exceeded that of the Mungiki itself."ii The violent terrorist activities in Kenya have increased since 2011. -

Islamist Militias and Rebel Groups Across Africa

Islamist Militias and Rebel Groups across Africa By Caitriona Dowd August 2012 Introduction The escalation of violent conflict in Nigeria and Somalia in recent years, and the early successes of Islamist factions in overtaking territory in Northern Mali following the coup in early 2012, have drawn attention to the role of Islamist groups in violence across the African continent. The capacity and perceived threat of these groups has been further highlighted by speculation of linkages and coordination between distinct groups across Africa and beyond (BBC News, 26 June 2012). This paper seeks to explore this phenomenon through data recorded and published through the Armed Conflict Location & Event Dataset (ACLED) from 1997 to July 2012. From this analysis, we present three key findings: the first is that violent Islamist activity on the African continent has increased sharply in recent years, both in absolute terms, and as a proportion of overall political conflict events. Secondly, this increase in violence has coincided with an expansion of the countries in which operatives are active. While a considerable share of the increase in violent Islamist activity can be attributed to an intensification of violence in a small number of key countries (Somalia and Nigeria, notably), there has been a concomitant increase in Islamist activity in new spaces, with a discernible spread south- and east-ward on the continent. Thirdly, commonalities and discrepancies within and across violent Islamist groups reveal differential objectives, strategies and modalities of violence on the continent. This paper proceeds with a definition of violent Islamist groups, a review of the geography of Islamist militancy on the African continent, and an analysis of commonalities and discrepancies across distinct militant Islamist groups. -

Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 4, December 2013 “ R2P in Practice”: Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya Abdullahi Boru Halakhe The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs, events and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource and a forum for governments, international institutions and non-governmental organizations on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. Acknowledgments: This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany. About the Author: Abdullahi Boru Halakhe is a security and policy analyst on the Horn of Africa and Great Lakes regions. Abdullahi has represented various organizations as an expert on these regions at the UN and United States State Department, as well as in the international media. He has authored and contributed to numerous policy briefings, reports and articles on conflict and security in East Africa. Previously Abdullahi worked as a Horn of Africa Analyst with International Crisis Group working on security issues facing Kenya and Uganda. As a reporter with the BBC East Africa Bureau, he covered the 2007 election and subsequent violence from inside Kenya. Additionally, he has worked with various international and regional NGOs on security and development issues. Cover Photo: Voters queue to cast their votes on 4 March 2013 in Nakuru, Kenya. -

Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues

U.S.-Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 23, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42967 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-Kenya Relations: Current Political and Security Issues Summary The U.S. government views Kenya as a strategic partner and anchor state in East Africa, and as critical to counterterrorism efforts in the region. Kenya has repeatedly been a target of terrorist attacks, and, as the September 2013 attack on an upscale Nairobi shopping mall underscores, terrorist threats against international and domestic targets in Kenya remain a serious concern. Kenya’s military plays a key role in regional operations against Al Shabaab in Somalia. The Al Qaeda-affiliated Somali insurgent group has claimed responsibility for the Westgate Mall attack ostensibly in response to Kenya’s military offensive against the group across the Somali border. The incident is the deadliest terrorist attack in Kenya since the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombing and the group’s first successful large-scale operation in the Kenyan capital. Kenya ranks among the top U.S. foreign aid recipients in the world, receiving significant development, humanitarian, and security assistance in recent years. The country, which is a top recipient of police and military counterterrorism assistance on the continent, hosts the largest U.S. diplomatic mission in Africa. Nairobi is home to one of four major United Nations offices worldwide. The election in March 2013 of President Uhuru Kenyatta and Vice President William Ruto complicates the historically strong relationship between Kenya and the United States.