(PINUS LONGAEVA DK BAILEY) CALLED PROMETHEUS B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart, Trees & Shrubs

Excerpted from ©2001 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the publisher. click here to BUY THIS BOOK INTRODUCTION HOW THE BOOK IS ORGANIZED Conifers and broadleaved trees and shrubs are treated separately in this book. Each group has its own set of keys to genera and species, as well as plant descriptions. Plant descriptions are or- ganized alphabetically by genus and then by species. In a few cases, we have included separate subspecies or varieties. Gen- era in which we include more than one species have short generic descriptions and species keys. Detailed species descrip- tions follow the generic descriptions. A species description in- cludes growth habit, distinctive characteristics, habitat, range (including a map), and remarks. Most species descriptions have an illustration showing leaves and either cones, flowers, or fruits. Illustrations were drawn from fresh specimens with the intent of showing diagnostic characteristics. Plant rarity is based on rankings derived from the California Native Plant Society and federal and state lists (Skinner and Pavlik 1994). Two lists are presented in the appendixes. The first is a list of species grouped by distinctive morphological features. The second is a checklist of trees and shrubs indexed alphabetically by family, genus, species, and common name. CLASSIFICATION To classify is a natural human trait. It is our nature to place ob- jects into similar groups and to place those groups into a hier- 1 TABLE 1 CLASSIFICATION HIERARCHY OF A CONIFER AND A BROADLEAVED TREE Taxonomic rank Conifer Broadleaved tree Kingdom Plantae Plantae Division Pinophyta Magnoliophyta Class Pinopsida Magnoliopsida Order Pinales Sapindales Family Pinaceae Aceraceae Genus Abies Acer Species epithet magnifica glabrum Variety shastensis torreyi Common name Shasta red fir mountain maple archy. -

Balkan Vegetation

Plant Formations in the Balkan BioProvince Peter Martin Rhind Balkan Mixed Deciduous Forest These forests vary enormously but usually include a variety of oak species such as Quercus cerris, Q. frainetto, Q. robur and Q. sessiliflora, and other broadleaved species like Acer campestris, Carpinus betulus, Castanea sative, Juglans regia, Ostrya carpinifolia and Tilia tomentosa. Balkan Montane Forest Above about 1000 m beech Fagus sylvatica forests often predominate, but beyond 1500 m up to about 1800 m various conifer communities form the main forest types. However, in some cases conifer and beech communities merge and both reach the tree line. The most important associates of beech include Acer platanoides, Betula verrucosa, Corylus colurna, Picea abies, Pyrus aucuparia and Ulmus scabra, while the shrub layer often consists of Alnus viridis, Euonymous latifolius, Pinus montana and Ruscus hypoglossum. The ground layer is not usually well developed and many of the herbaceous species are of central European distribution including Arabis turrita, Asperula muscosa, Cardamine bulbifera, Limodorum abortivum, Orthilia seconda and Saxifraga rotundifolia. Of the conifer forests, Pinus nigra (black pine) often forms the dominant species particularly in Bulgaria, Serbia and in the Rhodope massif. Associated trees may include Taxus buccata and the endemic Abies bovisii-regis (Macedonian fir), while the shrub layer typically includes Daphne blagayana, Erica carnea and the endemic Bruckenthalia spiculifolia (Ericaceae). In some areas there is a conifer forest above the black pine zone from about 1300 m to 2400 m in which the endemic Pinus heldreichii (Bosnian pine) predominates. It is often rather open possibly as a consequence of repeated fires. -

Description of the Ecoregions of the United States

(iii) ~ Agrl~:::~~;~":,c ullur. Description of the ~:::;. Ecoregions of the ==-'Number 1391 United States •• .~ • /..';;\:?;;.. \ United State. (;lAn) Department of Description of the .~ Agriculture Forest Ecoregions of the Service October United States 1980 Compiled by Robert G. Bailey Formerly Regional geographer, Intermountain Region; currently geographer, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and originally published as an unnumbered publication by the Intermountain Region, USDA Forest Service, Ogden, Utah In April 1979, the Agency leaders of the Bureau of Land Manage ment, Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Geological Survey, and Soil Conservation Service endorsed the concept of a national classification system developed by the Resources Evaluation Tech niques Program at the Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, to be used for renewable resources evaluation. The classifica tion system consists of four components (vegetation, soil, landform, and water), a proposed procedure for integrating the components into ecological response units, and a programmed procedure for integrating the ecological response units into ecosystem associations. The classification system described here is the result of literature synthesis and limited field testing and evaluation. It presents one procedure for defining, describing, and displaying ecosystems with respect to geographical distribution. The system and others are undergoing rigorous evaluation to determine the most appropriate procedure for defining and describing ecosystem associations. Bailey, Robert G. 1980. Description of the ecoregions of the United States. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication No. 1391, 77 pp. This publication briefly describes and illustrates the Nation's ecosystem regions as shown in the 1976 map, "Ecoregions of the United States." A copy of this map, described in the Introduction, can be found between the last page and the back cover of this publication. -

Altitudinal and Polar Treelines in the Northern Hemisphere – Causes and Response to Climate Change

Umbruch 79 (3) 05.08.2010 23:45 Uhr Seite 139 Polarforschung 79 (3), 139 – 153, 2009 (erschienen 2010 Altitudinal and Polar Treelines in the Northern Hemisphere – Causes and Response to Climate Change by Friedrich-Karl Holtmeier1* and Gabriele Broll2 Abstract: This paper provides an overview on the main treeline-controlling dem Vorrücken der Baumgrenze in größere, wesentlich windigere Höhen factors and on the regional variety as well as on heterogeneity and response to relativ zunehmen. Die Verlagerung der Baumgrenze in größere Höhen und changing environmental conditions of both altitudinal and northern treelines. weiter nach Norden wird zu grundlegenden Veränderungen der Landschaft in From a global viewpoint, treeline position can be attributed to heat deficiency. den Hochgebirgen und am Rande von Subarktis/Arktis führen, die auch wirt- At smaller scales however, treeline position, spatial pattern and dynamics schaftliche Folgen haben werden. depend on multiple and often elusive interactions due to many natural factors and human impact. After the end of the Little Ice Age climate warming initiated tree establishment within the treeline ecotone and beyond the upper INTRODUCTION and northern tree limit. Tree establishment peaked from the 1920s to the 1940s and resumed again in the 1970s. Regional and local variations occur. In most areas, tree recruitment has been most successful in the treeline ecotone Global warming since the end of the “Little Ice Age” (about while new trees are still sporadic in the adjacent alpine or northern tundra. 1900) is bringing about socio-economic changes, shrinking Lack of local seed sources has often delayed tree advance to higher elevation. -

Species Interactions and Abiotic Effects on Stand Structure of Bristlecone Pine (Pinus Longaeva) and Limber Pine (Pinus Flexilis)

Species interactions and abiotic effects on stand structure of bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) Selene Arellano1, Anna Douglas2, Neira Ibrahimovic3 , Janette Jin1 1University of California, Berkeley; 2University of California, Santa Cruz; 3University of California, Los Angeles ABSTRACT Plants experience a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses based on their environmental conditions. Demographic stages—recruits, saplings, and adults—may react differently under stress. In this study, we examine how the factors of aspect, substrate, and competition affect the stand structure of Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis), which are among the few trees that can withstand the stressful subalpine environment. We surveyed an even distribution of north and south- facing slopes with both dolomite and granite substrate in the White Mountains of Inyo National Forest, California. We recorded the density of different demographic stages of both tree species and tested how neighboring trees affected the cone production of bristlecones. We found that the effect of aspect and substrate depended on the demographic stage. We also found no evidence of competition between bristlecone and limber. Taken together, our results suggest that abiotic factors are more important than biotic factors in determining bristlecone and limber establishment. Overall, we suggest that abiotic factors are more influential in shaping subalpine plant communities. Keywords: bristlecone pine, limber pine, competition, abiotic stress, stand structure INTRODUCTION and have low levels of phosphorus, which is an essential element for plant development Plants may experience extreme stress (Wright and Mooney 1965, Malhotra et al. when they are growing in environments with 2018). -

Trashing Our Treasures

Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America 2 Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America Kate Dylewsky and Nancy Pyne Environment America July 2012 3 Acknowledgments: Contents: The authors would like to thank Anna Aurilio for her guidance in this project. Introduction…………………………….……………….…...….. 5 Also thank you to Mary Rafferty, Ruth Musgrave, and Bentley Johnson for their support. California: 10 What’s at Stake………….…..……………………………..……. 11 Photographs in this report come from a variety of public domain and creative Legislative Threats……..………..………………..………..…. 13 commons sources, including contributors to Wikipedia and Flickr. Colorado: 14 What’s at Stake……..………..……………………..……..…… 15 Legislative Threats………………..………………………..…. 17 Minnesota: 18 What’s at Stake……………..………...……………….….……. 19 Legislative Threats……………..…………………...……..…. 20 Montana: 22 What’s at Stake………………..…………………….…….…... 23 Legislative Threats………………..………………...……..…. 24 Nevada: 26 What’s at Stake…………………..………………..……….…… 27 Legislative Threats…..……………..………………….…..…. 28 New Mexico: What’s at Stake…………..…………………….…………..…... 30 Legislative Threats………………………….....…………...…. 33 Oregon: 34 What’s at Stake………………....……………..…..……..……. 35 Legislative Threats………….……..……………..………..…. 37 Pennsylvania: 38 What’s at Stake………...…………..……………….…………. 39 Legislative Threats………....…….…………….…………..… 41 Virginia: 42 What’s at Stake………………...…………...…………….……. 43 Legislative Threats………..……………………..………...…. 45 Conclusion……………………….……………………………..… 46 References…………………..……………….………………….. -

San Francisco Mountains Forest Heserve, Arizona

Professional Paper No. 22 Series H, Forestry, 7 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR \ FOREST CONDITIONS lN 'fHE- SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAINS FOREST HESERVE, ARIZONA BY JOHN B. LEIBERG, THEODORE F. RIXON, AND ARTHUR DODWELL WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY F. G. PLUMMER ·wASHINGTON G 0 Y E R N 1\I E N T I' HI N T IN G 0 ];' F I C E 1904 CONT .. ENTS. Page.. Letter of transmittaL_. __._._. ____-_._._._ .. _._ .. _.. _. ______ . __ _._._._- __._. ________ ._· __________ .~ __ . ____ . __ .___ 9 Introdnetion.·.-_-_. ______________ ._._._._._._._. ___ .. _______ .___ -_._. __ . ___________ . ____ . _. _________ ---- _ ___ 11 Boundaries·. ___ .----- ___ .·.·-·-·-·-·-·-·-_._. __ . __________ ._ .. _.._._. ______ . _______________ . _____ .___ 11 Surface features ___ . _ _- ..·: ______ ._._._ ..·.- ___ .· _ _. _ _. __ . _ _. ___________ .: ___________ . ________ ._______ 13 Soil·. _. _: _. _.. __ _. .. _ . _. __ .. __. .· ..· .... _. _. _..: ____ _. __. __ _. .· __.. __ . ___ .. __ . __ . __ . __ .. _____ . ___ .. 15 Drainage_._. _ _. ___ . _____________________ . __________ _.:. _ _. ________ . ____ . ___ ------_________ 15 Forest and womllan<.l .· __ . __ . __ . __ . __ . _____ ·- : _.. ·_____ . ___________ . ____ .· __ . _____ . _....... _ _ 17 Zones or types of arborescent growth_ . _.·. _. __.: _. __ . _: __. ... ____ . _______ . __ . __ . _.. _.. ___ . _ 18 Aspect and character of timber belts ____ . -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

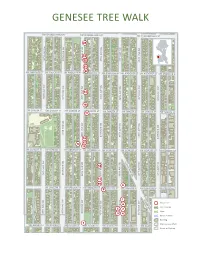

Genesee Tree Walk

S S S W W W S W G A D E N A A N D K L E O O A S V S T E A K E E R A S S T T S S S T T W S S 50TH AVE SW 50TH AVE S S SW S W 50TH AVE W W SW 50TH AVE SW C W W H O A G A A D N R E R L A E N D L G A K G E E S O O S O S K V T T E A N A E O E R S W S S S E T T T S T N T S S S S T S 4 9TH AVE SW S N 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW W 49TH AVE SW W W W W A O G A D N L E R A D A N E K E S O G E O K S V O T A E ! A E ! N 1 E R S S S 4 T S S T S T T S T ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 ! ! ! ! 1 1 ! S ! 1 ! E ! 2 ! ! ! 2 S S ! S 1 2 S ! 2 3 1 W ! 48TH AVE S 48TH AVE SW 48TH AVE SW C W 48TH AVE SW 5 48TH AVE S W W 6 ! W 2 3 W ! 4 W 8 2 1 1 9 H 0 7 A A G O A D N E R E R L A D L A N E K E O S G E O S K S V O T T A E A E O N E R S W T S ! ! ! ! S ! ! T S 1 1 1 T S T T N T 0 1 2 ! S ! S S S T R S 47TH AVE S W S 9 47 TH AVE SW 47TH AVE S W W W W 47TH AVE SW 47TH AVE SW W W A G O A D N E R L A E N D A E K G E O S O S K O V T E A E N A E E R S ! ! ! ! S S S T 5 3 S T T T T ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S S ! S ! ! S 46TH AVE SW 46TH AVE SW7 46 S TH AV W W E 4 SW W 46TH AVE SW 2 8 46TH AVE SW 6 W W W G L E A G O N A D N N E R L W A N D E A A Y K G E S O S W O S K O V T A E A E N A E R S S S S T S T T T S T W L S S S S S C 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW W W 45TH AVE SW W 45TH AVE SW W W H G K L A A E G O A N D N R N E R L W A L D N A E A E Y K O E G S S S O W S K V O T T E O A E A N E R W S S ! S S ! T S T T T N T S S T S S S W S I B W L T F S 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW W m W a r o t W u W e r a w c p i e e A l t u G d e O n e e D A s N C r i t r E n R v A a T L D o F g N i E n r A o e K r e O o G E u a O S P e p s S t V K O a u T y S E r E A A r N k u E e R i r S n S f S S a S T g T T T c T e 1 Trees for Seattle, a program of the City of Seattle, is dedicated to growing and maintaining healthy, awe- inspiring trees in Seattle. -

State of the World's Forest Genetic Resources Part 1

Forests and trees enhance and protect landscapes, ecosystems and production systems. They provide goods and services which are essential to the survival and well-being of all humanity. Forest genetic resources – the heritable materials maintained within and among tree and other woody plant species that are of actual or potential economic, environmental, scientific or societal value – are essential for the continued productivity, services, adaptation and evolutionary processes of forests and trees. This first volume of The State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources constitutes a major step in building the information and knowledge base required for action towards better conservation and sustainable management of forest genetic resources at the national, regional and international levels. The publication was prepared based on information provided by 86 countries, outcomes from regional and subregional consultations and commissioned thematic studies. It presents definitions and concepts related to forest genetic resources and a FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES review of their value; the main drivers of changes and the trends affecting these vital resources; and key emerging technologies. The central section analyses the current status of conservation and use of forest genetic resources on the basis of reports provided by the countries. The book concludes with recommendations for ensuring that present and future generations continue to benefit from forests and trees, both through innovations in practices and technologies and through enhanced attention -

Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines

Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines Andrew D. Bower, USDA Forest Service, Olympic National Forest, Olympia, WA; Sierra C. McLane, University of British Columbia, Dept. of Forest Sciences, Vancouver, BC; Andrew Eckert, University of California Davis, Section of Plenary Paper Evolution and Ecology, Davis, CA; Stacy Jorgensen, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Department of Geography, Manoa, HI; Anna Schoettle, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO; Sally Aitken, University of British Columbia, Dept. of Forest Sciences, Vancouver, BC Abstract—Conservation genetics examines the biophysical factors population structure using molecular markers and quanti- influencing genetic processes and uses that information to conserve tative traits and assessing how these measures are affected and maintain the evolutionary potential of species and popula- by ecological changes. Genetic diversity is influenced by the tions. Here we review published and unpublished literature on the evolutionary forces of mutation, selection, migration, and conservation genetics of seven North American high-elevation drift, which impact within- and among-population genetic five-needle pines. Although these species are widely distributed across much of western North America, many face considerable diversity in differing ways. Discussions of how these forces conservation challenges: they are not valued for timber, yet they impact genetic diversity can be found in many genetics texts have high ecological value; they are susceptible to the introduced (for example Frankham and others 2002; Hartl and Clark disease white pine blister rust (caused by the fungus Cronartium 1989) and will not be discussed here. ribicola) and endemic-turned-epidemic pests; and some are affect- ed by habitat fragmentation and successional replacement by other Why Is Genetic Diversity Important? species. -

Download PDF

How to See into the Past Look up at the night sky The light you see emerged many years, even millennia, ago and has just traveled close enough to Earth to be visible with the naked eye or a telescope. The nearest optical supernova in two decades, SN 2014J was discovered on January 21, 2014. SN 2014J occurred in the Cigar Galaxy and lies about 12 million light-years away. When this blast oc- curred, geologically speaking Earth was in the Miocene Epoch. Count the rings on a tree Dendrochronology is the study of growth rings, which scientists can use to date temperate zone trees. In contrast, tropical trees lack the dramat- ic seasonal changes that produces periods of rapid growth and dor- mancy that result in growth rings. In 1964 Donald Currey, a graduate student in the geography department at the University of North Caro- lina, unintentionally cut down the oldest living organism on the planet. In what became known as the “Prometheus Story,” Currey’s core sample tool became lodged in bristlecone pine and the park officials advised him to simply cut down the tree, rather than lose the tool and waste this research opportunity. The tree Currey cut down became known as Prometheus, which was estimated to be 4,900 years old. Currently the old- est known living tree, about 4,600 years old, is in the White Mountains of California; there are likely even older bristlecones that have not been dated. Look at the desert landscape Movement and changes in the earth’s geology are apparent in the striated layers of rock and dirt, especially visible in the desert’s barren landscape.