Trashing Our Treasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umbrella Falls Trail #667 Northwest Forest Pass Required Recreation Opportunity Guide May 15 - Oct 1

Umbrella Falls Trail #667 Northwest Forest Pass Required Recreation Opportunity Guide May 15 - Oct 1 Distance ........................................ 3.1 miles (one way) Elevation ....................................... 4550-5750 feet Snow Free .................................... July to October More Difficult Trail Highlights: This trail is on the southeast side of Mount Hood. The trail passes Umbrella Falls on the way to the Mount Hood Meadows Ski Area. The trail provides easy access to Timberline Trail #600. Trail Description: This trail begins at its junction with Timberline Trail #600, heads southeast and ends at its junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C. From Timberline Trail #600 (5,800’), the trail heads southeast through a meadow and crosses two small creeks. After 0.4 miles, the trail switches back several times before heading north another 0.3 mile to Mitchell Creek (5,540’). Cross Mitchell Creek on the wooden bridge and continue downhill (southeast) 0.5 mile to Mount Hood Meadows Road (5,200’). (This is a good place to start the hike). Cross Mount Hood Meadows Road and follow the trail north 0.25 mile to Umbrella Falls (5,250’). Continue past the falls 0.25 mile to the first junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C. Continue from the junction, crossing several ski runs, 1.3 miles to the second junction with Sahalie Falls Trail #667C and the end of this trail. Hikers can return on this trail or take Sahalie Falls Trail #667C 2.1 miles back to the first junction with this trail. Regulations & Leave No Trace Information: There are no bikes allowed between Timberline Trail #600 and Forest Road 3555. -

The Middle Rio Grande Basin: Historical Descriptions and Reconstruction

CHAPTER 4 THE MIDDLE RIO GRANDE BASIN: HISTORICAL DESCRIPTIONS AND RECONSTRUCTION This chapter provides an overview of the historical con- The main two basins are flanked by fault-block moun- ditions of the Middle Rio Grande Basin, with emphasis tains, such as the Sandias (Fig. 40), or volcanic uplifts, on the main stem of the river and its major tributaries in such as the Jemez, volcanic flow fields, and gravelly high the study region, including the Santa Fe River, Galisteo terraces of the ancestral Rio Grande, which began to flow Creek, Jemez River, Las Huertas Creek, Rio Puerco, and about 5 million years ago. Besides the mountains, other Rio Salado (Fig. 40). A general reconstruction of hydro- upland landforms include plateaus, mesas, canyons, pied- logical and geomorphological conditions of the Rio monts (regionally known as bajadas), volcanic plugs or Grande and major tributaries, based primarily on first- necks, and calderas (Hawley 1986: 23–26). Major rocks in hand, historical descriptions, is presented. More detailed these uplands include Precambrian granites; Paleozoic data on the historic hydrology-geomorphology of the Rio limestones, sandstones, and shales; and Cenozoic basalts. Grande and major tributaries are presented in Chapter 5. The rift has filled primarily with alluvial and fluvial sedi- Historic plant communities, and their dominant spe- ments weathered from rock formations along the main cies, are also discussed. Fauna present in the late prehis- and tributary watersheds. Much more recently, aeolian toric and historic periods is documented by archeological materials from abused land surfaces have been and are remains of bones from archeological sites, images of being deposited on the floodplain of the river. -

Cabins Availability Charts in This Issue

ISSN 098—8154 The Newsletter of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club Volume 35, Number 3 118 Park Street, S.E., Vienna, VA 22180-4609 March 2006 www.patc.net PATC Signs Lease Agreement with ATC for Management of Bears Den n Dec. 20, 2005, PATC President Tom OJohnson signed a two-year lease agree- ment with ATC for management of the Bears Den Trail Center located on the Appalachian Trail just off of Rte. 7 in Virginia. There is an official marker on Rte. 7 west- bound just before the turnoff on to Rte. 601 for Bears Dens that reads as follows: Appalachian Trail and Bears Den This 2,100-mile-long hiking path passes through 14 states from Mount Katahdin, Maine, to Springer Mountain, Ga., along the ridges of the Appalachian Mountains. Conceived in 1921 by Benton MacKaye, the trail was completed in 1937. It was designated a National Scenic Trail in 1968. One-half mile to the south along the trail is Bears Den, a Dave Starzell Bob WIlliams and Tom Johnson signing the agreement to transfer See Bears Den page management of Bears Den to PATC Web Site Breakthrough! Cabins Availability Charts In This Issue . Council Fire . .2 ne of PATC’s crown jewels is its 32 navigate forward or backward a week at a Tom’s Trail Talk . .3 rentable cabins, many only for member time through the calendar. The starting day of Chain Saw Course . .3 O Annual Family Weekend . .4 use. For the first time you may now visit the the week will be the day you are visiting the Smokeys Environmental Impact . -

Lewis and Clark Mount Hood Final Wilderness Map 2009

!( !( !( !( !( !( !( R. 4 E. R. 5 E. R. 6 E. R. 7 E. R. 8 E. R. 9 E. R. 10 E. R. 11 E. R. 12 E. R. 13 E. (!141 !( !( !( n (!14 o ER 142 t RIV (! !( 14 (! 30 !( g IA ¤£ HOOD a MB 84 e LU ¨¦§ RIVER n Ar CO !( i WYETH VIENTO c !( i en !( h ROCKFORD MOSIER !( c 14 S !( !( (! ROWENA s l a ¤£30 a CASCADE 00 ! n !( 20 o LOCKS OAK GROVE i !( !( t !35 a R. ( 30 W N Hood !(VAN ¤£ T. HORN 2 !( 197 ge ¤£ N. or CRATES G BONNEVILLE 84 POINT !( ¨¦§ ODELL !( !( Gorge Face !( 84 500 er ¨¦§ (! 140 v MARK O. HATFIELD !( !( (! i !( R WILDERNESS !( !( a HOOD RIVER WASCO i !( WINANS THE DALLES !( b COUNTY COUNTY um !( l DEE !( !( !( o E !( ER . C IV F Wahtum R k. !( Ea Lake g . le r Cr. MULTNOMAH A C BI FALLS!( l . M a R LU p d O O E C o o . F T. 14 H 17 T. ! . ( k Ý BRIDAL k . !( H 1 VEIL F 1 . o N. ! M o !( N. !( !( 84 d MOUNT § R FAIRVIEW ¨¦ 15 HOOD 30 !( Ý . !( !( !( Byp 0 TROUTDALE CORBETT LATOURELL FALLS 0 ¤£ 0 2 Ý13 !( !( Ý20 !( HOOD RIVER WASCO PARKDALE !( !( !( !( !( COUNTY COUNTY TWELVEMILE SPRINGDALE Bu Ý18 Larch Mountain ll CORNER R 16 !( !( Ý10 u Ý ENDERSBY n !( !( R Lost !( Bull Run . Middle Fork !( Lake !( !( !( GRESHAM Reservoir #1 Hood River ! !( T. T. !( Elk Cove/ 1 Mazama 1 S. Laurance 35 S. !( Ý12 (! ORIENT Ý MULTNOMAH COUNTY Lake DUFUR !( !( !( CLACKAMAS COUNTY ! COTRELL Bull Run ! !( Lake Shellrock ile Cr. -

Borrador Preliminar Del Plan De Gestion De Recursos Y De La Tierra Propuesto

Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos Borrador preliminar del plan de gestión de recursos y de la tierra propuesto para el Bosque Nacional de Carson [Versión 2] Condados de Río Arriba, Taos, Mora y Colfax en Nuevo México Región Sur del Servicio Forestal Publicación Nro. Diciembre de 2017 De acuerdo con la ley federal de los derechos civiles y con los reglamentos y políticas de derechos civiles del Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos (USDA), el USDA, sus agencias, oficinas y empleados, y las instituciones que participen o administren los programas del USDA tienen prohibido cualquier tipo de discriminación por raza, color, origen nacional, religión, sexo, identidad de género (incluida la expresión de género), orientación sexual, discapacidad, edad, estado civil, estado familiar/parental, ingresos derivados de un programa de asistencia pública, creencias políticas, represalia o acto de venganza por actividad previa a los derechos civiles, en cualquiera de los programas o actividades realizadas o financiadas por el USDA (no todos los fundamentos son aplicables a todos los programas). Los plazos para la presentación de recursos y quejas varían según el programa o el incidente. Las personas con discapacidades que requieran de medios de comunicación alternativos para obtener información sobre el programa (p. ej., Braille, caracteres grandes, cintas de audio, lenguaje estadounidense de señas, etc.) deben contactar a la agencia responsable o al TARGET Center del USDA al (202) 720-2600 (voz y TTY), o ponerse en contacto con el USDA a través del Servicio Federal de Transmisiones al (800) 877-8339. Asimismo, la información de los programas puede estar disponible en otros idiomas además del inglés. -

Summer 2009 Shenandoah National Park Shenandoahshenandoah Overlookoverlook

National Park Service Park Visitor Guide U.S. Department of the Interior Summer 2009 Shenandoah National Park ShenandoahShenandoah OverlookOverlook Park Emergency Number America at Its Best . 1-800-732-0911 “…with the smell of the woods, and the wind Shenandoah Online in the trees, they will forget the rush and strain of all the other long weeks of the year, To learn more about Shenandoah, and for a short time at least, the days will be or to plan your next visit, visit our good for their hearts and for their souls." website: www.nps.gov/shen –President Franklin Roosevelt speaking about vacationers to national parks in his speech at Shenandoah National Park’s dedication, July 3, 1936. aaaaaaah… the sound of relief, winding down, changing perspective. There’s no better place to do it Athan Shenandoah National Park. Shenandoah was designed from the ground up for an escape to nature. As you enter the park and navigate the gentle curves of Skyline Drive, you have to slow down! For one thing, the speed limit is 35mph, but even if it weren’t you’d be compelled to let up on the gas to take in the breathtaking views at every turn and the wildlife grazing by the road. And if one of those views tempts you to pull off at an Overlook, get out of your car, Your Pet in the Park take a deep breath and say, “Aaaaaaaah.” Pets are welcome in the park—if they do not disturb other visitors or the It seems that these days, more than ever, we all need a place animals who call this park home. -

H. Con. Res. 62

IV 112TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 62 To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of Shenandoah National Park. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JUNE 23, 2011 Mr. GOODLATTE (for himself, Mr. WOLF, Mr. MORAN, Mr. WITTMAN, Mr. SCOTT of Virginia, and Mr. CONNOLLY of Virginia) submitted the fol- lowing concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Natural Resources CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of Shenandoah National Park. Whereas this historical milestone for Shenandoah National Park corresponds with the Civil War sesquicentennial, enriching the heritage of both the Commonwealth of Vir- ginia and our Nation; Whereas, in the early to mid-1920s, with the efforts of the citizen-driven Shenandoah Valley, Inc., and the Shen- andoah National Park Association, the congressionally appointed Southern Appalachian National Park Com- mittee recommended that Congress authorize the estab- lishment of a national park in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia for the purposes of uniting the western na- tional park experience to the populated eastern seaboard; VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:20 Jun 24, 2011 Jkt 099200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6300 E:\BILLS\HC62.IH HC62 smartinez on DSK6TPTVN1PROD with BILLS 2 Whereas, in 1935, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes accepted the land deeds from the Commonwealth of Virginia and, on July 3, 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated Shenandoah National Park ‘‘to this and to succeeding generations for the recreation and -

Nomination Form

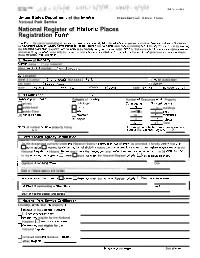

United States Depaftment of the Interior Presidential Sites Theme National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Th~sfwm 19for use in nominating or resuesting determinstbns of eligibility for lndii~dualprowrties w distnm. SHI ~nstmaions~n GWhos lor Cemplsting Namnal slbgtsfctr Foms (National Regtster Bulletln 16). Complete each Item by marking "w" In the approprratr hw or by entenng the raquwted rnlormatm. If an item doss not apply to the 0- being dmumemed. enter "MIA" for "not app~rcabte.''Foa functions. styles, marenas. and areas of sign~ficance,enter only the caregomas and subcatmnes Ilstmd In ths ~nstructlona.For addltlonal space use cwtrnuat~onsheets (Form lG900a). Tyw all entrres 1. Name of Property hlslor~cname Camp Hoover other namsdsite number Cam~sRaidan 2. Location street & number Shenandoah Natsonal Park nd for publication city, town Graves Yill I.x v~cin~ty state Vir~inia- - cde VA county Yad isan code VA-! 11 z~pcad9 2277 I 3. CSassltlestlan -. Ownersh~pof Prowrty Category of Property Number af Resources mth~nProperty Eprivate [7 building(s) Contr~butlng Noncantrrbutrng public-locat distrrcl 3 Q buildings public-State stte 4 sftes @ public-fed- G structura 16 11 Szructures • object o Qobjects 2 -1 27 Total Nams of related multiple property listing: Numbsr of contributing resources prevrousl~ N, A liwed rn the National Regtstsr 0 4. StatelFederal Agency CerLlflcstion As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of t 968, as amended, I hereby cenlty that this 1 nan!namn viquslt for dehrmination of eligibilfty mans the dmumentatlon standards for registering propenlar in the 1 National Register 01 Historic Places and Nnr the pawural and prof-iwl rqulretnenta set fonh in 36 CFR Part MI. -

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1—SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO No. 2—TAOS—RED RIVER—EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3—ROSWELL—CAPITAN—RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO No. 4—SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO No. 5—SILVER CITY—SANTA RITA—HURLEY, NEW MEXICO No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO No. 7—HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATON- CAPULIN MOUNTAIN—CLAYTON No. 8—MOSlAC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE—ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VOLCANOES No. 10—SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO No. 11—CUMBRE,S AND TOLTEC SCENIC RAILROAD C O V E R : REDONDO PEAK, FROM JEMEZ CANYON (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by John Whiteside) Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by Robert W . Talbott) WHITEWATER CANYON NEAR GLENWOOD SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, a n d History edited by PAIGE W. CHRISTIANSEN and FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1972 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1979, Socorro James R. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE of SOUTHERN WASHINGTON by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2460 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE OF SOUTHERN WASHINGTON By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein When I climbed Mount Adams {17-18 August 1945] about 1950 m (6400') most of the landscape is mantled I think I found the answer to the question of why men by dense forests and huckleberry thickets. Ten radial stake everything to reach these peaks, yet obtain no glaciers and the summit icecap today cover only about visible reward for their exhaustion... Man's greatest 2.5 percent (16 km2) of the cone, but in latest Pleis experience-the one that brings supreme exultation tocene time (25-11 ka) as much as 80 percent of Mount is spiritual, not physical. It is the catching of some Adams was under ice. The volcano is drained radially vision of the universe and translating it into a poem by numerous tributaries of the Klickitat, White Salmon, or work of art ... Lewis, and Cis pus Rivers (figs. 1, 2), all of which ulti William 0. Douglas mately flow into the Columbia. Most of Mount Adams and a vast area west of it are Of Men and Mountains administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which has long had the dual charge of protecting the Wilderness Area and of providing a network of logging roads almost INTRODUCTION everywhere else. The northeast quadrant of the moun One of the dominating peaks of the Pacific North tain, however, lies within a part of the Yakima Indian west, Mount Adams, stands astride the Cascade crest, Reservation that is open solely to enrolled members of towering 3 km above the surrounding valleys. -

Compilation of Precambrian Isotopic Ages

COMPILATION OF PRECAMBRIAN ISOTOPIC AGES IN NEW MEXICO bY Paul W. Bauer and Terry R. Pollock New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Open-File Report 389 January, 1993 New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Socorro, New Mexico 87801 Table of Contents Introduction . 1 Acknowledgments . 4 Figure 1. Map of New Mexico showing exposures of Precambrian rocks, and mountains and physiographic provinces used in database 5 Table A. Geochronology laboratories listed in database, with number of determinations . Table B. Constants used for age recalculations Figure 2. Histograms of isotopic ages . Figure 3. Graph of igneous rocks which have U-Pb zircon plus Rb-Sr, K-Ar, or @ArP9Arage determinations . 8 Part I. List of isotopic age determinations by isotopic method . 9 a. U-Pbages . 9 b.Pb-Pb model ages . 16 c. Rb-Srages . 21 d. K-Arages . 38 e. Ar-Arages . 42 f. Sm-Nd, Fission-track, Pb-alpha, and determinations of uncertain geochronologic significance 45 Part 11. Comprehensive list of all isotopic age determinations withcomplete data listing . 48 Part III. List of isotopic age determinations by mountain range 94 Part IV. List of isotopic age determinations by rock unit . 102 Part V. List of isotopic age determinations by county 114 Part VI. References . 121 Appendix 1. List of areadesignations by county . 127 1 Introduction This compilation contains information on 350 published and unpublished radiometric ages for Precambrian rocks of New Mexico. All data were collected from original references, entered into a REFLEX database, and sorted according to several criteria. Based on author’s descriptions, samples were located as precisely as possible on 7.5’ topographic quadrangle maps, which are on file at the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources. -

Recco® Detectors Worldwide

RECCO® DETECTORS WORLDWIDE ANDORRA Krimml, Salzburg Aflenz, ÖBRD Steiermark Krippenstein/Obertraun, Aigen im Ennstal, ÖBRD Steiermark Arcalis Oberösterreich Alpbach, ÖBRD Tirol Arinsal Kössen, Tirol Althofen-Hemmaland, ÖBRD Grau Roig Lech, Tirol Kärnten Pas de la Casa Leogang, Salzburg Altausee, ÖBRD Steiermark Soldeu Loser-Sandling, Steiermark Altenmarkt, ÖBRD Salzburg Mayrhofen (Zillertal), Tirol Axams, ÖBRD Tirol HELICOPTER BASES & SAR Mellau, Vorarlberg Bad Hofgastein, ÖBRD Salzburg BOMBERS Murau/Kreischberg, Steiermark Bischofshofen, ÖBRD Salzburg Andorra La Vella Mölltaler Gletscher, Kärnten Bludenz, ÖBRD Vorarlberg Nassfeld-Hermagor, Kärnten Eisenerz, ÖBRD Steiermark ARGENTINA Nauders am Reschenpass, Tirol Flachau, ÖBRD Salzburg Bariloche Nordkette Innsbruck, Tirol Fragant, ÖBRD Kärnten La Hoya Obergurgl/Hochgurgl, Tirol Fulpmes/Schlick, ÖBRD Tirol Las Lenas Pitztaler Gletscher-Riffelsee, Tirol Fusch, ÖBRD Salzburg Penitentes Planneralm, Steiermark Galtür, ÖBRD Tirol Präbichl, Steiermark Gaschurn, ÖBRD Vorarlberg AUSTRALIA Rauris, Salzburg Gesäuse, Admont, ÖBRD Steiermark Riesneralm, Steiermark Golling, ÖBRD Salzburg Mount Hotham, Victoria Saalbach-Hinterglemm, Salzburg Gries/Sellrain, ÖBRD Tirol Scheffau-Wilder Kaiser, Tirol Gröbming, ÖBRD Steiermark Schiarena Präbichl, Steiermark Heiligenblut, ÖBRD Kärnten AUSTRIA Schladming, Steiermark Judenburg, ÖBRD Steiermark Aberg Maria Alm, Salzburg Schoppernau, Vorarlberg Kaltenbach Hochzillertal, ÖBRD Tirol Achenkirch Christlum, Tirol Schönberg-Lachtal, Steiermark Kaprun, ÖBRD Salzburg