Imoeey I]\. Il ENGLISH LOVE LYRICS: THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

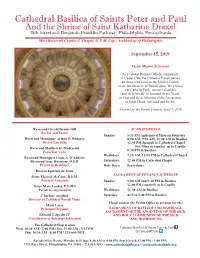

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul And the Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel 18th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Most Reverend Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Archbishop of Philadelphia September 15, 2019 Parish Mission Statement As a vibrant Roman Catholic community in Center City, the Cathedral Parish Serves all those who come to the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. We profess our Catholic Faith, minister to others and welcome all, as founded on the Word of God and the celebration of the Sacraments of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Adopted by the Parish Council, April 5, 2016 Reverend Gerald Dennis Gill MASS SCHEDULE Rector and Pastor Sunday: 5:15 PM Anticipated Mass on Saturday Reverend Monsignor Arthur E. Rodgers 8:00 AM, 9:30 AM, 11:00 AM in Basilica Rector Emeritus 12:30 PM Spanish in Cathedral Chapel Sta. Misa en español, en la Capilla Reverend Matthew K. Biedrzycki 6:30 PM in Basilica Parochial Vicar Weekdays: 7:15 AM, 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Monsignor Louis A. D’Addezio Saturdays: 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Isaac Haywiser, O.S.B. Priests in Residence Holy Days: See website Deacon Epifanio de Jesus SACRAMENT OF PENANCE SCHEDULE Sister Eleanor McCann, R.S.M. Pastoral Associate Sunday: 9:00 AM and 5:30 PM in Basilica 12:00 PM (español) en la Capilla Sister Mary Luchia, P.V.M.I Parish Evangelization Weekdays: 11:30 AM in Basilica Charlene Angelini Saturday: 4:15 to 5:00 PM in Basilica Director of Cathedral Parish Music Please contact the Parish Office to arrange for the: Mark Loria SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM AND MARRIAGE, Principal Organist SACRAMENT OF THE ANOINTING OF THE SICK, Edward J. -

Metaphysical Poetry

METAPHYSICAL POETRY Metaphysical poetry is a group of poems that share common characteristics: they are all highly intellectualized, use rather strange imagery, use frequent paradox and contain extremely complicated thought. Literary critic and poet Samuel Johnson first coined the term 'metaphysical poetry' in his book Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1179-1781). In the book, Johnson wrote about a group of 17th-century British poets that included John Donne, George Herbert, Richard Crashaw, Andrew Marvell and Henry Vaughan. He noted how the poets shared many common characteristics, especially ones of wit and elaborate style. What Does Metaphysical Mean? The word 'meta' means 'after,' so the literal translation of 'metaphysical' is 'after the physical.' Basically, metaphysics deals with questions that can't be explained by science. It questions the nature of reality in a philosophical way. • Here are some common metaphysical questions: • Does God exist? • Is there a difference between the way things appear to us and the way they really are? Essentially, what is the difference between reality and perception? • Is everything that happens already predetermined? If so, then is free choice non-existent? • Is consciousness limited to the brain? Metaphysics can cover a broad range of topics from religious to consciousness; however, all the questions about metaphysics ponder the nature of reality. And of course, there is no one correct answer to any of these questions. Metaphysics is about exploration and philosophy, not about science and math. CHARACTERISTICS OF METAPHYSICAL POETRY • The group of metaphysical poets that we mentioned earlier is obviously not the only poets or philosophers or writers that deal with metaphysical questions. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Gifts of the Spirit Handbook

the gifts ofthe Spirit The Gifts of the Spirit a contemporary resource pack First published in the United Kingdom in 2009 Pauline Books & Media Slough SL3 6BS, UK www.pauline-uk.org notes and creative ideas Copyright © Pauline Books & Media UK 2009 All rights reserved. Scripture quotations — Christian Community Bible contents © 1999 Bernardo Hurault, Claretian Publications Used with permission introduction 3 Images and materials on this CD ROM are for educational and pastoral use only, not for com- wisdom 4 mercial distribution in any form. Reproduction by any means, including electronic transmission, right judgement 6 is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. courage 8 understanding 10 Text written by Matthew van Duyvenbode knowledge 12 Consultants — Alice Murphy and Sue Cooper reverence 14 Edited by Maria Rosario D Agtarap fsp wonder and awe 16 my gift 18 Designed by Mary Louise Winters fsp music discussion starters 20 BOOKS & MEDIA www.pauline-uk.org Middle Green, Slough SL3 6BS – UK T 01753 577629 F 01753 511809 E [email protected] Pauline Books & Media is an expression of the ministry of the Daughters of St Paul. introduction Everyone wants to love and be loved. The difficulty is in knowing how. When love goes wrong, real damage can be done to people. But when love works it is spectacular. It is a many-splendoured thing. And this resource pack lays out some of those splendours to help people find true love in their life, a love that will last and set them free. The fireworks and other big emotions we experience in loving are to be treasured and enjoyed. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

The Sacred and the Secular

Part 3 The Sacred and the Secular Allegory of Fleeting Time, c. 1634. Antonio Pereda. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. “I write of groves, of twilights, and I sing L The court of Mab, and of the Fairy King. I write of hell; I sing (and ever shall) Of heaven, and hope to have it after all.” —Robert Herrick, “The Argument of His Book” 413 Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 00413413 U2P3-845482.inddU2P3-845482.indd 413413 11/29/07/29/07 10:19:5210:19:52 AMAM BEFORE YOU READ from the King James AKG Images Version of the Bible he Bible is a collection of writings belong- ing to the sacred literature of Judaism and- TChristianity. Although most people think of the Bible as a single book, it is actually a collec- tion of books. In fact, the word Bible comes from the Greek words ta biblia, meaning “the little books.” The Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh, contains the sacred writings of the Jewish people and chronicles their history. The Christian Bible was originally written in Greek. It contains most of the same texts as the Hebrew Bible, as well as twenty-seven additional books called the New Testament. The many books of the Bible were written at different times and contain various types The Creation of Heaven and Earth (detail of writing—including history, law, stories, songs, from the Chaos), 1200. Mosaic. Monreale proverbs, sermons, prophecies, and letters. Cathedral, Sicily. Protestants living in Switzerland; and the Rheims- “I perceived how that it was impossible Douay Bible, translated by English Roman to establish the lay people in any truth Catholics living in France. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Copyrighted Material

335 Index a “After You Get What You Want, You “Aba Daba Honeymoon” 151 Don’t Want It” 167 ABBA 313 Against All Odds (1984) 300 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein “Age of Not Believing, The” 257 (1948) 155 Aguilera, Christina 323, 326 Abbott, Bud 98–101, 105, 109, 115 “Ah Still Suits Me” 87 ABC 229–230 “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” 78 Abdul, Paula 291 AIDS 317–318 About Face (1953) 151 “Ain’t There Anyone Here for “Abraham” 110–111 Love?” 170 Absolute Beginners (1986) 299 Aladdin (1958) 181 Academy Awards 46, 59, 73–74, 78, 82, Aladdin (1992) 309–310, 312, 318, 330 89, 101, 103, 107, 126, 128, 136, 140, Aladdin II, The Return of Jafar 142, 148–149, 151, 159, 166, 170, 189, (1994) 309 194, 200, 230, 232–233, 238, 242, 263, Alamo, The (1960) 187 267, 271, 282, 284, 286, 299, 308–309, Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938) 83, 319, 320–321 85–88 Ackroyd, Dan 289 Alice in Wonderland (1951) 148 Adler, Richard 148 Alice in Wonderland: An X‐Rated Admiral Broadway Revue (1949) 180 Musical Fantasy (1976) 269 Adorable (1933) 69 All‐Colored Vaudeville Show, An Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the (1935) 88 Desert, The (1994) 319 “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” 88–89 African AmericansCOPYRIGHTED 13–17, 21, 24, 28, 40, All New MATERIAL Mickey Mouse Club, The 43, 54–55, 78, 87–89, 109–111, 132, (1989–94) 326 163–164, 193–194, 202–203, 205–209, “All Out for Freedom” 102 213–216, 219, 226, 229, 235, 237, All‐Star Revue (1951–53) 179 242–243, 258, 261, 284, 286–287, 289, All That Jazz (1979) 271–272, 292, 309, 293–295, 314–315, 317–319 320, 322 “After the Ball” 22 “All You Need Is Love” 244 Free and Easy? A Defining History of the American Film Musical Genre, First Edition. -

Introduction

Notes Quotations from Love’s Martyr and the Diverse Poetical Essays are from the first edition of 1601. (I have modernized these titles in the text.) Otherwise, Shakespeare is quoted from The Riverside Shakespeare, ed. G. Blakemore Evans, 2nd edn (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997). Jonson, unless otherwise noted, is quoted from Ben Jonson, ed. C. H. Herford and Percy and Evelyn Simpson, 11 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925–52), and Edmund Spenser from The Works of Edmund Spenser: A Variorum Edition, ed. Edwin Greenlaw, Charles Osgood and Fredrick Padelford, 10 vols (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1932–57). Introduction 1. Colin Burrow, ‘Life and Work in Shakespeare’s Poems’, Shakespeare’s Poems, ed. Stephen Orgel and Sean Keilen (London: Taylor & Francis, 1999), 3. 2. J. C. Maxwell (ed.), The Cambridge Shakespeare: The Sonnets (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), xxxiii. 3. See, for instance, Catherine Belsey’s essays ‘Love as Trompe-l’oeil: Taxonomies of Desire in Venus and Adonis’, in Shakespeare in Theory and Practice (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 34–53, and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’, in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry, ed. Patrick Cheney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 90–107. 4. William Empson, Essays on Shakespeare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 1. 5. I admire the efforts of recent editors to alert readers to the fact that all titles imposed on it are artificial, but there are several reasons why I reluctantly refer to it as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’. Colin Burrow, in The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), chooses to name it after its first line, the rather inelegant ‘Let the bird of lowdest lay’, which, out of context, to my ear sounds more silly than solemn. -

Titles of Mary

Titles of Mary Mary is known by many different titles (Blessed Mother, tion in the Americas and parts of Asia and Africa, e.g. Madonna, Our Lady), epithets (Star of the Sea, Queen via the apparitions at Our Lady of Guadalupe which re- of Heaven, Cause of Our Joy), invocations (Theotokos, sulted in a large number of conversions to Christianity in Panagia, Mother of Mercy) and other names (Our Lady Mexico. of Loreto, Our Lady of Guadalupe). Following the Reformation, as of the 17th century, All of these titles refer to the same individual named the baroque literature on Mary experienced unforeseen Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ (in the New Testament) growth with over 500 pages of Mariological writings and are used variably by Roman Catholics, Eastern Or- during the 17th century alone.[4] During the Age of thodox, Oriental Orthodox, and some Anglicans. (Note: Enlightenment, the emphasis on scientific progress and Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, and Mary Salome are rationalism put Catholic theology and Mariology often different individuals from Mary, mother of Jesus.) on the defensive in the later parts of the 18th century, Many of the titles given to Mary are dogmatic in nature. to the extent that books such as The Glories of Mary (by Other titles are poetic or allegorical and have lesser or no Alphonsus Liguori) were written in defense of Mariology. canonical status, but which form part of popular piety, with varying degrees of acceptance by the clergy. Yet more titles refer to depictions of Mary in the history of 2 Dogmatic titles art. -

St. Stephen Parish

St. Stephen Parish SaintStephenSF.org | 451 Eucalyptus Dr., San Francisco CA 94132 | Church 415 681-2444 StStephenSchoolSF.org | 401 Eucalyptus Dr., San Francisco 94132 | School 415 664-8331 Weekday Mass: 8:00 a.m. Reconciliation: Saturday 3:30 p.m. or by appt. Vigil Mass Saturday 4:30 p.m., Sunday Mass 8:00, 9:30, 11:30 a.m. & 6:45 p.m. May 26 ,2019 Sixth Sunday of Easter How many of us have ever wished, in moments of indecision, that God would send us a clear sign about what we are called to do at that moment – perhaps an angel to tell us exactly what God wants? At times like these, when we’re surrounded by tur- moil and violence, it can be easy to feel that God has left us alone to fend for ourselves – that we’re left on our own with no clear direction. But the readings today, as we come ever nearer to the great Feast of Pentecost, are reassuring. We are not alone, but have God, the Church, and the people around us to give us guidance and support when we need it – as long as we’re open to the different ways the Holy Spirit operates in our daily lives. In the first reading, we see the Church, our brothers and sisters in the faith, as a support system to help us understand what is required of us. The earliest Gentile disciples in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia were misled into believing they had to follow the ancient Mosaic law if they were to be saved – if they were to be Chris- tians.