Seabury 3E Sample-46417

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RIP Hugh Hefner: 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships

RIP Hugh Hefner: 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships By Katie Gray It’s the end of an era. American icon, publishing pioneer, activist and the ultimate Playboy – sadly passed away recently, at age 91. RIP Hugh Hefner! Since being founded in 1953, Playboy has been a notable American men’s magazine that specializes in lifestyle and entertainment. Of course it is most notable for featuring beautiful women. What would a Playboy be without beautiful women? The gorgeous women featured on the cover and in the magazine, are known as Playmates and Centerfolds. Playboy enterprises is a huge company, with many different divisions. They have accessories and clothing to Playboy TV. From 2005 until 2010, Hugh Hefner and his girlfriends, starred in the E! reality seriesThe Girls Next Door. It starred Hugh Hefner, and the celebrity couple – his three girlfriends: Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt and Kendra Wilkinson. Who could forget the theme song “Come on-a My House” and the funny adventures that played out on the screen? Hugh Hefner has notoriety for always being surrounded by beautiful women, and dating several of them at once. Hefner was married a couple of times, and is the father of four children. His celebrity relationships were always highly publicized. They often all lived with him at the famous Playboy Mansion. It doesn’t feel real that Hef is gone, but his memory and Playboy – will live on! Cupid has compiled the 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships: 1. Holly, Bridget & Kendra: Come on-a My House! Perhaps Hugh Hefner’s most famous celebrity relationship, was with Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson. -

Kathleen Wallman Kathleen Wallman Pllc 9332 Ramey Lane Great Falls, Virginia 22066-2025

KATHLEEN WALLMAN KATHLEEN WALLMAN PLLC 9332 RAMEY LANE GREAT FALLS, VIRGINIA 22066-2025 May 1, 2006 Marlene Dortch, Esq. Secretary Federal Communications Commission th 445 12 St., S.W. Washington, DC 20554 Re: Letter Submission in MB Docket No. 05-192 Dear Ms. Dortch: The America Channel submits this letter ex parte in the Commission’s MB Docket # 05-192. SUMMARY I. THE COMMISSION SHOULD NOT BE DIVERTED FROM THE PUBLIC INTEREST QUESTION CENTRAL TO THIS TRANSACTION II. THE TRANSACTION PARTIES’ REBUTTAL REGARDING DISPARATE TREATMENT OF INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMERS IS INADEQUATE AND DIVERSIONARY III. THE TRANSACTION PARTIES’ RESPONSES TO THE INFORMATION REQUESTS ARE UNRESPONSIVE, AND CONTAIN ADMISSIONS OF DISCRIMINATION IV. INCONSISTENCY OF COMCAST’S STATEMENTS V. COMMUNICATIONS WITH COMCAST; REFUSAL TO ADD THE AMERICA CHANNEL TO FAMILY TIER APPENDICES A. SUMMARY RESEARCH FINDINGS B. STATEMENTS REGARDING INDEPENDENT CHANNELS C. PROGRAMMING FOUND ON COMCAST-OWNED NETWORKS D. LETTER EXCHANGE WITH COMCAST I. THE COMMISSION SHOULD NOT BE DIVERTED FROM THE PUBLIC INTEREST QUESTION CENTRAL TO THIS TRANSACTION Adverse petitions in this proceeding have now been before the FCC for nearly ten months, and the transaction parties still have not adequately refuted the overwhelming evidence of discrimination in 1 programming decisions – decisions consistently favoring affiliated programming and disadvantaging independent programmers -- that has poured into the record. Empirical evidence presented by The America Channel demonstrates that in a 2 ½ year study -

ND Admits 3484 from Strongest Pool Ever

r--------------------.~------------~--------~-~-.----------~--------~--~------.-------------------------------------~~~~~~------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOLUME 40: ISSUE 120 MONDAY. APRIL 10,2006 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM ND admits 3,484 from strongest pool ever year's pool - the largest ever - said. 'That's not the norm across By KAREN LANGLEY was up 13 percent from last year, the country." Associate NeWs Editor . Saracino said. The Office of Saracino said private U.S. col 52% Male Undergraduate Admissions sent leges have an average yield in the If statistics on accepted appli acceptance letters to 3,484 stu 20 percent range. 48% Female cants for next year's freshman dents, and Saracino said the This year's admitted students - class are any indicator, the incom University hopes to enroll 1,985 who represent all 50 states and top 5.6% in class ing class of 2010 - like each students for the fall 2006 fresh 32 foreign countries - are on freshman class in recent years - man class. Notification letters average slightly more academical PRIJECTEI 1380 SAT will be the strongest academically were mailed March 30. ly qualified than last year's admit in Notre Dame's history. The size of incoming classes ted students. The admitted stu 2116 31ACT This year's selections were must remain static due to the dents' average class rank places made from a pool of applicants University's physical constraints, them in the top 4.5 percent of ElllllEI 84% Catholic who boasted academic statistics so the number of students admit their high school classes, and they equal to those of Notre Dame's ted each year is based on previ boast an average SAT score of 1:1111 23% alumni incoming freshman class nine ous years' yields - or the per 1398 out of a possible 1600 and children years ago, Director of Admissions centage of admitted students who an average ACT score of 32 out of 1,985 students Dan Saracino said April4. -

Arbiter, February 12 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 2-12-2007 Arbiter, February 12 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT VOICE OF BOISE STATE SINCE 1933 MONDAY,FEBRUARY 12, 2006 ar. iteronIine.'CJln ISSUE 41. VOLUME 24. FIRSTISSUE FR'EE .• 6 BIZTECH. ;~~;-;------- . The wait Is "I finally over. Microsoft from Windows Vista Is now available, ". but Is your computer too old to " run the new operating system? ee S ~: BY DUSTIN LAPRAY Managing Editor H?w much cash ya got there chums? '\" CULTURE ---------------------------- It costs more and more every fall to pay for an education at Boise State between a five and seven percent increase, so many of these requests will PAGE 6 University. There is an undercurrent of growth, both in buildings and in be denied, no matter their importance to the future of BSU. Some will be Experience the singles' S.A.D. educational goals, pulsing through our hallways, tracing the synapses in given discounted funds and others will be negated entirely. alternative to Valentine's Day our brains and lacing the conversation on the quad. The discussion process is complicated. -

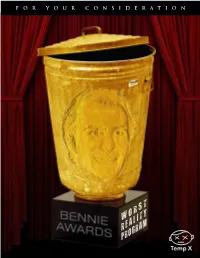

Worst Reality Program PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK the Vexcon Pest Removal Team Helps to Rid Clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E Their Extreme Pest Cases

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION WORST REALITY PROGRAM PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK The Vexcon pest removal team helps to rid clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E their extreme pest cases. Performance series featuring Criss Angel, a master Criss Angel: Mindfreak illusionist known for his spontaneous street A&E performances and public shows. Reality series which focuses on bounty hunter Duane Dog the Bounty Hunter "Dog" Chapman, his professional life as well as the A&E home life he shares with his wife and their 12 children. A docusoap following the family life of Gene Simmons, Gene Simmons Family Jewels which include his longtime girlfriend, Shannon Tweed, a A&E former Playmate of the Year, and their two children. Reality show following rock star Dee Snider along with Growing Up Twisted A&E his wife and three children. Reality show that follows individuals whose lives have Hoarders A&E been affected by their need to hoard things. Reality series in which the friends and relatives of an individual dealing with serious problems or addictions Intervention come together to set up an intervention for the person in A&E the hopes of getting his or her life back on track. Reality show that follows actress Kirstie Alley as she Kirstie Alley's Big Life struggles with weight loss and raises her two daughters A&E as a single mom. Documentary relaity series that follows a Manhattan- Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force based federal task that tracks down fugitives in the Tri- A&E state area. Individuals with severe anxiety, compulsions, panic Obsessed attacks and phobias are given the chance to work with a A&E therapist in order to help work through their disorder. -

Teenagers Discuss the Girls Next Door

MEDIA@LSE Electronic MSc Dissertation Series Compiled by Prof. Robin Mansell and Dr. Bart Cammaerts Bunny Talk: Teenagers Discuss The Girls Next Door Jennifer Barton, MSc in Media and Communications Other dissertations of the series are available online here: http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/media@lse/mediaWorkingPapers/ Dissertation submitted to the Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2009, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Media and Communication. Supervised by Dr. Nancy Thumim. Published by Media@LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science ("LSE"), Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. The LSE is a School of the University of London. It is a Charity and is incorporated in England as a company limited by guarantee under the Companies Act (Reg number 70527). Copyright in editorial matter, LSE © 2010 Copyright, Jennifer Barton © 2010. The authors have asserted their moral rights. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this dissertation are not necessarily those of the compilers or the LSE. MSc Dissertation Jennifer Barton Bunny Talk: Teenagers Discuss The Girls Next Door Jennifer Barton ABSTRACT The sexualisation of the mainstream media is hardly cause for surprise nowadays, even when shows are targeting a teenage audience. -

2017 Delinquent Publication

############ Delinquent Advertising List DelqAdvertisingList.rpt 2:53 PM Cuyahoga Page -1 of 1 2018 Pay 2019 Delinquent Property number Owner Name Property Description Acres Valuations Amount 0010 - Bay Village 201-08-014 CANNATA, KENNETH A 98 BAYV 1/39TH INT IN BLOCK A 0005 AL 0.1804 67660 3,433.04 201-08-049 Gomola Robert J 92 SP 585.62FT S OF CL W LAKE RD 0009 0.1756 46030 859.19 201-14-005 Waters, Stephen R 97 WILLGEMAR 0033 ALL 0.2617 66050 5,965.01 201-15-048 Vick, James 91 BAYENTPRS#2 0017 ALL 0.3444 85930 183.82 201-17-045 Quinn, John J 91 WP 490.09FT EP 0.3673 72450 169.60 201-17-046 THOMSON, THOMAS E. 91 NWC BEXLEY DR 0.3616 73750 278.09 201-18-040 POSZA EVA & KOHLER, SHARON91 NP 1222.56FT N OF CL WOLF RD 0.4050 60520 2,848.15 201-23-036 BORST, CHARLES A & BORST, LI 81 BAY-GARDENS EST#3 0001 ALL 0.4644 106050 186.44 201-25-017 RYAN THOMAS P & JENNIFER 81 CON-WELL #2 0121 0.3576 108890 232.94 201-26-035 HARTRANFT, PAUL W. & CATHLE81 BROOKE ESTATES SUB 0033 ALL 0.3508 80960 7,659.05 201-28-041 SIGNATURE BUILDING CONCEPT98 NP 1042.45FT SWC 80 FT IN REAR 0.4192 63040 6,383.16 201-35-007 Shiry Dora R 92 DIETRICH DELUXE HOMES#1 0014 A 0.2796 109830 219.07 201-37-033 WATERS, ROBERT J 92 NP 205N OF WEST- LAWN DR 0.3719 72700 7,184.87 202-03-035 Escovar Barbara A TRUSTEE 93 THOMAS TERRY 0001 ALL 0.3551 132340 746.79 202-04-055 O'Connell, Christopher M. -

How American Idol Constructs Celebrity, Collective Identity, and American Discourses

AMERICAN IDEAL: HOW AMERICAN IDOL CONSTRUCTS CELEBRITY, COLLECTIVE IDENTITY, AND AMERICAN DISCOURSES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Amanda Scheiner McClain May, 2010 i © Copyright 2010 by Amanda Scheiner McClain All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a three-pronged study examining American themes, celebrity, and collective identity associated with the television program American Idol. The study includes discourse analyses of the first seven seasons of the program, of the season seven official American Idol message boards, and of the 2002 and 2008 show press coverage. The American themes included a rags-to-riches narrative, archetypes, and celebrity. The discourse-formed archetypes indicate which archetypes people of varied races may inhabit, who may be sexual, and what kinds of sexuality are permitted. On the show emotional exhibitions, archetypal resonance, and talent create a seemingly authentic celebrity while discourse positioning confirms this celebrity. The show also fostered a complication-free national American collective identity through the show discourse, while the online message boards facilitated the formation of two types of collective identities: a large group of American Idol fans and smaller contestant-affiliated fan groups. Finally, the press coverage study found two overtones present in the 2002 coverage, derision and awe, which were absent in the 2008 coverage. The primary reasons for this absence may be reluctance to criticize an immensely popular show and that the American Idol success was no longer surprising by 2008. By 2008, American Idol was so ingrained within American culture that to deride it was to critique America itself. -

Bridget Marquardt (You Know BRIDGET MARQUARDT Her from the Girls Next the California Native Felt Right at Home in Door) As She Visits the the 50Th State

GETAWAY HULA TIME The blonde bombshell gets her groove on with Miss Hawaii USA, Aureana Tseu, on the Big Island. “Doing the hula is easier than I thought,” jokes Bridget. BeachHawaii just got hotter: OK! joins the Travel Channel’s Bridget Marquardt (you know BRIDGET MARQUARDT her from The Girls Next The California native felt right at home in Door) as she visits the the 50th state. “I’m going back to Hawaii,” islands’ seductive spots Bridget, here in Kona, tells OK!. “There’s so much to do!” 64 MARCH 23, 2009 OK! Bunny UP, UP AND A The TV host took toway the skies for a tour and saw the Big Island’s active volcano, Kilauea. “The lava tube flows right into the ocean,” explains Bridget. oodbye, Playboy Mansion, hello, world! Bridget Marquardt, 35, spent seven years as one of Hugh Hefner’s G(three!) lady loves and starred on The Girls Next Door. Now, she’s got a new man, director Nick Carpenter, 29, and a new gig hosting the Travel Channel’s Bridget’s Sexiest Beaches, premiering March 12 at 10 p.m. Here, she dishes to OK! about the show’s adventures, love, and life without Hef. What’s been your favorite location? Hawaii was amazing, but we had the most fun in Jamaica and Australia. Both Kendra [Wilkinson] and Holly [Madison, Bridget’s Girls Next Door co-stars] make guest appearances on our Southern California episode. Any sadness after leaving the mansion? It hasn’t hit me yet that I’m not living HANgiNG TOugh there anymore. -

Saturday Morning, Aug. 28

SATURDAY MORNING, AUG. 28 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sat (cc) The Emperor’s The Replace- Little League Baseball World Series, International Championship. 2/KATU 2 2 New School ments (TVG) (Live) (cc) 5:00 The Early Show (N) (cc) Noonbory and the Busytown Mys- Fusion North- Garden Time Weddings Port- Sabrina, the Ani- WTA Tennis U.S. Open Series - Pilot Pen, Final. (Live) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (Cont’d) Super 7 teries (TVY) west home. land Style (TVG) mated Series Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) 3-2-1 Penguins! Babar (cc) (TVY) Willa’s Wild Life Paid Paid Paid 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) (cc) (TVY7) (cc) (TVY7) A Place of Our Donna’s Day Star- SciGirls Horsing Angelina Balle- Animalia (cc) WordGirl (cc) The Electric Com- Fetch! With Ruff Victory Garden P. Allen Smith’s Sewing With Martha’s Sewing 10/KOPB 10 10 Own (TVG) ring Donna Around. (TVG) rina: Next (TVY) (TVY7) pany (TVY) Ruffman (TVY) Edible. (TVG) Garden Home Nancy (TVG) Room (TVG) Good Day Oregon Saturday (N) Saved by the Bell Awesome Adven- Dog Tales (cc) Animal Rescue Jack Hanna’s Into Gladiators 2000 This Week in 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVG) tures (N) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) the Wild (TVPG) Baseball (N) Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Natural Hor- Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 mones Sing Along With The Dooley and Dr. -

Meet the Judges

Meet The Judges Joseph Creagh San luis Obispo, California Joseph Conrad Creagh is a proud alumnus of The Dance Spot in Fullerton, California. He began his professional career at a young age as a series regular on The Disney Channel’s Kids Incorporated, and created the role of Jake in Walt Disney Pictures’ Newsies! Having established a twenty-five year career in the entertainment industry, Joseph has performed in 11 countries over three decades encompassing film, television, theater, and stage productions. Joseph has created choreography and staging for the Walt Disney Company, Holland America Cruise Line, Cedar Fair, Mel B, Days of Our Lives, Elvira “Mistress of the Dark”, Ann-Margret, and Andy Williams, as well as numerous award-winning, celebrity magic shows, corporate events, and theme park attractions. Joseph is pleased to be on staff at Studio @ Ryan’s American Dance in San Luis Obispo, California and thankful for the opportunities to motivate and inspire dancers across the country. Joseph is also a proud member of the UnMasked panel of instructors interacting with, and helping shape the next generation of young artists. Lisa Schroeder Minneapolis, MN Lisa is from Minnesota where she grew up dancing at her mother’s studio. She continued her training attending multiple conventions and workshops across the country. Lisa graduated with a B.A. degree in dance from the University of Minnesota, where she was a member of the URepCo dance company, and was also a member of the Minnesota Timberwolves Reebok Performance Team. She has been teaching and choreographing over the past 30 years, with numerous choreography and top score awards. -

RIP Hugh Hefner: 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships

RIP Hugh Hefner: 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships By Katie Gray It’s the end of an era. American icon, publishing pioneer, activist and the ultimate Playboy – sadly passed away recently, at age 91. RIP Hugh Hefner! Since being founded in 1953, Playboy has been a notable American men’s magazine that specializes in lifestyle and entertainment. Of course it is most notable for featuring beautiful women. What would a Playboy be without beautiful women? The gorgeous women featured on the cover and in the magazine, are known as Playmates and Centerfolds. Playboy enterprises is a huge company, with many different divisions. They have accessories and clothing to Playboy TV. From 2005 until 2010, Hugh Hefner and his girlfriends, starred in the E! reality seriesThe Girls Next Door. It starred Hugh Hefner, and the celebrity couple – his three girlfriends: Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt and Kendra Wilkinson. Who could forget the theme song “Come on-a My House” and the funny adventures that played out on the screen? Hugh Hefner has notoriety for always being surrounded by beautiful women, and dating several of them at once. Hefner was married a couple of times, and is the father of four children. His celebrity relationships were always highly publicized. They often all lived with him at the famous Playboy Mansion. It doesn’t feel real that Hef is gone, but his memory and Playboy – will live on! Cupid has compiled the 5 Best Playboy Playmate Celebrity Relationships: 1. Holly, Bridget & Kendra: Come on-a My House! Perhaps Hugh Hefner’s most famous celebrity relationship, was with Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson.