UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIDS EAT FREE!! U & Corn on the Cob Snow Crab Grouper Shfirnp Open Mon - Sat @11 Am Sunday 9:00Am $ 95 with Frfinnh Frifis & R.Nrn on Thf» R.Nh 2330 Palm Ridge Rd

INDAY NIGHT IS PRIME TIME!! Served with baked Idaho potato KIDS EAT FREE!! U & corn on the cob Snow Crab Grouper ShFirnp Open Mon - Sat @11 am Sunday 9:00am $ 95 with Frfinnh Frifis & r.nrn on thf» r.nh 2330 Palm Ridge Rd. Sanibel Island With the Purchase of One 15 and up Adult Entr You Receive One Kids Meal for Children 10 & uni 37 items on the "Consider the Kids" menu. Not good with any other promotion or discount. All specials subject to availability. This promotion good through February 26,2006 and subject to change at any o-nn -12:00 noon Master Card, Visa, Discover Credit Cards Accepted No Holidays. Must present ad. 2Q Week of February 10- 16, 2006 ISLANDER 49ers of Periwinkle Park BY LAURA NICKERSON Inickerson @ breezenewspapers.com Everyone knows Periwinkle Park, the quaint on island trailer park where mobile homes and park models rub shoul- ders with nature in a rich setting of trees, flowers, and wildlife, as well as caged birds and monkeys. Many "Parkers" live in their little homes year round, and others come just for winter. Of the latter group, the ones who Join Us fora Hapfij Valentine's % Tuesday, JeBruary14th Lighflhouse lASaterfront ^Restaurant - Photo by LAURA NICKERSON at tPort SaniBeC SS/Carina The 49ers enjoy the shade canopy which they expanded to accomodate their increased numbers. 1 MILE BEFORE THE SANIBEL TOLLBOOTH come in their own RVs (recreational vehicles) at an appoint- guys got together and built them for everyone in need. ed time of year, like migratory birds are a breed unto them- Most members have favorite pastimes on island, and many selves.The park's newest RV sites are the winter homes of an of them volunteer their time at non-profit organizations. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

How VICKI GUNVALSON Balances a Thriving Life Insurance Business with Being Outrageous on the Real Housewives of Orange County

INTERVIEW How VICKI GUNVALSON balances a thriving life insurance business with being outrageous on The Real Housewives Of Orange County. 12 InsuranceNewsNet Magazine » February 2019 THE SELF-MADE, REAL HOUSEWIFE OF ORANGE COUNTY INTERVIEW icki Wolfsmith was a At the time of our interview, the latest money and in order for me to do that I 28-year-old single mother controversy from the show stemmed from needed to stay focused and do what I do of two children, working Gunvalson’s accusation that fellow cast best. So many people were just fine taking as a self-taught bookkeeper member Kelly Dodd was using cocaine. care of what they were doing. for her father’s construc- Not for the first time, rumors swirled that I was raised very privileged. My father tion business outside Chicago. Gunvalson might be fired from the show, was very successful. So I wanted that for She described herself as a child of privi- but then again, she has been stirring the my children and I wasn’t going to wait Vlege who had few options in her life at that pot for 13 seasons. for a man to give it to me. Which is dif- point. But when she talked with a friend In this conversation with Publisher ferent than a lot of the women on the about her life as an insurance agent, a Paul Feldman, Gunvalson revealed why Housewives. A lot of the women have door opened. she is so driven and how she deals with acquired their wealth from their men and She went through that door with noth- the Vicki haters of the world. -

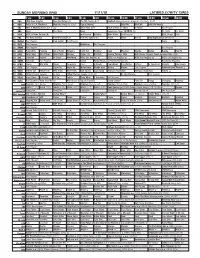

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Shaping Embodiment in the Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture

SHAPING EMBODIMENT IN THE SWAN: FAN AND BLOG DISCOURSES IN MAKEOVER CULTURE by Beth Ann Pentney M.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2003 B.A. (Hons.), Laurentian University, 2002 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Beth Ann Pentney 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Beth Ann Pentney Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Shaping Embodiment in The Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lara Campbell Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Helen Hok-Sze Leung Senior Supervisor Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Mary Lynn Stewart Supervisor Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Zoë Druick Internal Examiner Associate Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Cressida Heyes External Examiner Professor, Philosophy University of Alberta Date Defended/Approved: ______________________________________ ii Partial Copyright Licence Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Star Channels, Feb. 18-24

FEBRUARY 18 - 24, 2018 staradvertiser.com REAL FAKE NEWS English comedian John Oliver is ready to take on politicians, corporations and much more when he returns with a new season of the acclaimed Last Week Tonight With John Oliver. Now in its fi fth season, the satirical news series combines comedy, commentary and interviews with newsmakers as it presents a unique take on national and international stories. Premiering Sunday, Feb. 18, on HBO. – HART Board meeting, live on ¶Olelo PaZmlg^qm_hkAhghenenlkZbemkZglbm8PZm\aebo^Zg]Ûg]hnm' THIS THURSDAY, 8:00AM | CHANNEL 55 olelo.org ON THE COVER | LAST WEEK TONIGHT WITH JOHN OLIVER Satire at its best ‘Last Week Tonight With John hard work. We’re incredibly proud of all of you, In its short life, “Last Week Tonight With and rather than tell you that to your face, we’d John Oliver” has had a marked influence on Oliver’ returns to HBO like to do it in the cold, dispassionate form of a politics and business, even as far back as press release.” its first season. A 2014 segment on net By Kyla Brewer For his part, Bloys had nothing but praise neutrality is widely credited with prompt- TV Media for the performer, saying: “His extraordinary ing more than 45,000 comments on the genius for rich and intelligent commentary is Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) s 24-hour news channels, websites and second to none.” electronic filing page, and another 300,000 apps rise in popularity, the public is be- Oliver has worked his way up through the comments in an email inbox dedicated to Acoming more invested in national and in- entertainment industry since starting out as a proposal that would allow “priority lanes” ternational news. -

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr. Paul Nassif Discusses Being Single, Skincare and Spin-Off Shows Interview by Lori Bizzoco. Written by Stephanie Sacco. Dr. Paul Nassif is more than a doctor on reality TV. He’s a renowned facial plastic surgeon and skincare specialist. Though people may remember him from The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, he’s even more recognizable for his E! reality series, Botched which he co-hosts with former RHOC star, Dr. Terry Dubrow. The success of Botched has even led to a few upcoming spin-off shows, Botched By Nature and Botched Post- Op. Last week, Nassif spoke to us in an exclusive celebrity interview about the upcoming spin-off shows, his new anti- aging skincare line and his very single relationship status. Reality TV Star Dr. Paul Nassif Talks ‘Botched’ Success Back when Nassif first developed the concept for Botched and pitched the show, his co-host was doubtful, calling Nassif “crazy” for wanting to put plastic surgery on TV. “Now look at us,” the former RHOBH star says. Botched is in its third season and the show has led to multiple spin-off series. One of the many reasons for the show’s success is that all the cases are legitimate, and Nassif and Dubrow are passionate about their clients. The doctors really enjoy helping their patients through their issues. Nassif says the role of a plastic surgeon is “part doctor and part therapist.” Although extreme cases are common in this line of work, the reality TV star shares that the worst is yet to come. -

SPANISH FORK PAGES 1-20.Indd

November 14 - 20, 2008 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, November 14 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey b News (N) b CBS Evening News (N) b Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Threshold” The Price Is Right Salutes the NUMB3RS “Charlie Don’t Surf” News (N) b (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight (N) b Troops (N) b (N) b Letterman (N) KJZZ 3 High School Football The Insider Frasier Friends Friends Fortune Jeopardy! Dr. Phil b News (N) Sports News Scrubs Scrubs Entertain The Insider The Ellen DeGeneres Show Ac- News (N) World News- News (N) Access Holly- Supernanny “Howat Family” (N) Super-Manny (N) b 20/20 b News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4 tor Nathan Lane. (N) Gibson wood (N) b line (N) wood (N) (N) b News (N) b News (N) b News (N) b NBC Nightly News (N) b News (N) b Deal or No Deal A teacher returns Crusoe “Hour 6 -- Long Pig” (N) Lipstick Jungle (N) b News (N) b (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night KSL 5 News (N) to finish her game. b Jay Leno (N) b TBS 6 Raymond Friends Seinfeld Seinfeld ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (G, ’39) Judy Garland. (8:10) ‘Shrek’ (’01) Voices of Mike Myers. -

Body Work and the Work of the Body

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 2, No. 1 (2013): 113-131 Body Work and the Work of the Body Jeffrey P. Bishop e cult of the body beautiful, symbolizing the sacrament of life, is celebrated everywhere with the earnest vigour that characterized rit- ual in the major religions; beauty is the last remaining manifestation of the sacred in societies that have abolished all the others. Hervé Juvin HE WORLD OF MEDICINE has always been focused on bod- ies—typically ailing bodies. Yet recently, say over the last century or so, medicine has gradually shied its emphasis away from the ailing body, turning its attention to the body Tin health. us, it seems that the meaning of the body has shied for contemporary medicine and that it has done so precisely because our approach to the body has changed. Put in more philosophical terms, our metaphysical assumptions about the body, that is to say our on- tologies (and even the implied theologies) of the body, come to shape the way that a culture and its medicine come to treat the body. In other words, the ethics of the body is tied to the assumed metaphys- ics of the body.1 is attitude toward the body is clear in the rise of certain con- temporary cultural practices. In one sense, the body gets more atten- tion than it ever has, as evident in the rise of the cosmetics industry, massage studios, exercise gyms, not to mention the attention given to the body by the medical community with the rise in cosmetic derma- tology, cosmetic dentistry, Botox injections, and cosmetic surgery. -

Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Bio-logics of Bodily Transformation: Biomedicine and Makeover TV DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Visual Studies by Corella Ann Di Fede Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Lucas Hilderbrand, Chair Associate Professor Fatimah Tobing Rony Associate Professor Jennifer Terry Assistant Professor Allison Perlman 2016 © 2016 Corella Ann Di Fede DEDICATION To William Joseph Di Fede, My brother, best friend and the finest interlocutor I will ever have had. He was the twin of my own heart and mind, and I am not whole without him. My mother for her strength, courage and patience, and for her imagination and curiosity, My father whose sense of humor taught me to think critically and articulate myself with flare, And both of them for their support, generosity, open-mindedness, and the care they have taken in the world to live ethically, value every life equally, and instill that in their children. And, to my Texan and Sicilian ancestors for lending me a history full of wild, defiant spirits ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii INTRODUCTION 1 Biopolitical Governance in Pop Culture: Neoliberalism, Biomedicine, and TV Format 3 Health: Medicine, Morality, Aesthetics and Political Futures 11 Biomedicalization, the Norm, and the Ideal Body 15 Consumer-patient, Privatization and Commercialization of Life 20 Television 24 Biomedicalized Regulation: Biopolitics and the Norm 26 Emerging