Shaping Embodiment in the Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

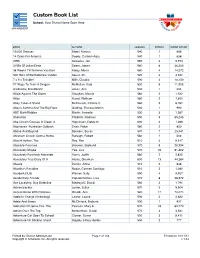

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

Comcast Enhances on Demand and Hdtv Lineups With

____________________________________________________________________________________ Press Contact Comcast: Jenni Moyer (215) 851-3311 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE COMCAST ENHANCES ON DEMAND AND HDTV LINEUPS WITH DISCOVERY’S REAL WORLD PROGRAMMING Country’s leading entertainment and communications company brings customers more ways to enjoy their favorite Discovery programs PHILADELPHIA, PA (June 21, 2004) – Comcast and Discovery Communications today announced a multi-year agreement to make selected programs from Discovery Networks U.S. available as part of Comcast’s ON DEMAND service, and to begin offering Discovery HD Theater in selected markets where Comcast offers high-definition television (HDTV) service. Beginning later this summer, Comcast Digital Cable customers in markets where its ON DEMAND video-on-demand service is offered will be able to select from more than 70 hours of programs from Discovery Networks U.S. each month at no extra charge. The lineup of ON DEMAND programming from Discovery Networks U.S. initially will include programs such as: Discoveries This Week Gilad’s Body in Motion American Chopper In Shape with Sharon Mann Monster Garage Urban Fitness Trading Spaces Destination USA What Not to Wear America’s Best Beaches While You Were Out The Planet’s Funniest Animals Rides The Jeff Corwin Experience A Makeover Story Crocodile Hunter A Wedding Story Croc Files Christopher Lowell Ready, Set, Learn Make Room for Baby Adoption Tales In addition, Discovery HD Theater, Discovery Networks’ 24-hour HD channel, will be added to Comcast’s HDTV package over the next several months. Comcast Digital Cable customers with HDTV service will be able to enjoy Discovery HD Theater’s lineup of favorite shows like Trading Spaces, Rides and The Jeff Corwin Experience, as well as original specials and documentaries in a crystal-clear HD format, all at no additional charge. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr. Paul Nassif Discusses Being Single, Skincare and Spin-Off Shows Interview by Lori Bizzoco. Written by Stephanie Sacco. Dr. Paul Nassif is more than a doctor on reality TV. He’s a renowned facial plastic surgeon and skincare specialist. Though people may remember him from The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, he’s even more recognizable for his E! reality series, Botched which he co-hosts with former RHOC star, Dr. Terry Dubrow. The success of Botched has even led to a few upcoming spin-off shows, Botched By Nature and Botched Post- Op. Last week, Nassif spoke to us in an exclusive celebrity interview about the upcoming spin-off shows, his new anti- aging skincare line and his very single relationship status. Reality TV Star Dr. Paul Nassif Talks ‘Botched’ Success Back when Nassif first developed the concept for Botched and pitched the show, his co-host was doubtful, calling Nassif “crazy” for wanting to put plastic surgery on TV. “Now look at us,” the former RHOBH star says. Botched is in its third season and the show has led to multiple spin-off series. One of the many reasons for the show’s success is that all the cases are legitimate, and Nassif and Dubrow are passionate about their clients. The doctors really enjoy helping their patients through their issues. Nassif says the role of a plastic surgeon is “part doctor and part therapist.” Although extreme cases are common in this line of work, the reality TV star shares that the worst is yet to come. -

Rektorer Protesterar Mot Sparkrav I Skolan

24 JULI 2007 ÅRG 18, NR 30 Sommarupplaga +7.700 ex Nu 74.500 ex! Besöksadress Värmdövägen 205, Nacka Red 555 266 20, [email protected] Annons 555 266 10 nvp.se NYHETER 10 TEST 12-13 NYHETER 7 KRÖNIKA 10 ”Busschauffören NVP testar Cillas badstig ”Fel klädd för att räddade mitt liv” turistslingan blev en väg träffa drömtjejen” Språkresan blev Rektorer protesterar en mardröm VÄRMDÖ Tre unga Värm- dötjejers språkresa till Brigh- ton i England blev inte vad de tänkt sig. Värdfamiljen gav dem väldigt lite mat och mot sparkrav i skolan de var berusade och bråkade varje dag. Efter en tvist i All- VÄRMDÖ 19 miljoner. Så mycket ska Värmdös gemensamt protestbrev, säger ”går till historien männa reklamationsnämn- grundskolor spara de kommande tre åren. Nu har som det största som någonsin presenterats av po- den får flickorna nu rätt till prisavdrag. ➤ rektorerna fått nog av det sparkrav som man, i ett litikerna i kommunen”. 8 ➤ 8 Ö sökes till konstprojekt NACKA/VÄRMDÖ Nästa sommar planerar några ös- terikiska performanceartis- ter ett konstprojekt på en ö. Nu undrar föreningen ”Mossutställningen” om det är någon som har en ö att låna ut. ➤ 15 SPORTEN Silver i Gothia Cup för Boo FF NACKA FOTBOLL Boo FF:s elvaåriga pojkar lyckades med bedriften att sluta på en andra plats i den prestigefulla turneringen Gothia Cup i Göteborg. La- get spelade jättebra och för- lorade en tät match i finalen mot Werder Bremens ut- vecklingslag. ➤ 21 Gabriel är Värmdös egen allsångskung FOTO: JENNY FRJING SIGGESTA När han inte leder 900 gospelsångare i kyrkan, 3 000 ungar i Himmelstalundshallen eller förfest i SVT, står han varje måndagkväll i juli på scenen i logen på Siggesta. -

Turning Dreams Into Cuss Their Short- and Long- 28 and Saturday, March 1 Term Development Plans from 9 A.M

WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 28-MARCH 1, 2014 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM LEGISLATIVE SESSION BOCC looks at Gun bills on tap funding By DARA KAM in common? Bills dealing with toast- tive session that starts The News Service of Florida For anyone who has er pastries and insurance Tuesday. As in previous been paying attention to policies are just two of years, many of them will plans TALLAHASSEE — the Florida Legislature more than a dozen gun-re- go nowhere, especially if Today What do Pop-Tarts and recently, the answer is lated measures lined By STEVEN RICHMOND property insurance have easy: Guns. up for the 2014 legisla- GUNS continued on 3A [email protected] Yard sale North Florida Animal The Board of County Rescue, 16800 County Rd. Commissioners met 137 in Wellborn, is holding Thursday morning to dis- a yard sale on Friday, Feb. Turning dreams into cuss their short- and long- 28 and Saturday, March 1 term development plans from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. both and financial priorities for days. The yard sale will Columbia County’s future. take place rain or shine. The workshop focused Proceeds will go to the res- on 13 key issues that will cue animals. play a significant role in the county’s budget delib- ALNF Art Exhibit erations leading up to Oct. The Art League of 1, the official start of Fiscal North Florida invites the Year 2014-15. community to the 9th “The idea is to progres- Annual Spring Members sively reach conclusions on Art Exhibit at the Levy various Performing Arts Center, COMING county Florida Gateway College. -

Politicians React to Proposed Spanish Bailout

ISSUE 24 (255) • 14 – 20 JUNE 2012 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI BUSINESS Politicians react Chasing competitiveness How to improve productivity is the question on many manageri- al minds. HT takes a look at Finn- to proposed LEHTIKUVA / VESA MOILANEN ish competitiveness. See page 8 Spanish bailout SUMMER GUIDE Party leaders divided over Finland’s role in the proposed bailout for Spanish banks. DAVID J. CORD brought down, or it should be pos- HELSINKI TIMES sible to chop up some banks,” Finn- ish Prime Minister Jyrki Katainen SPAIN has become the fourth euro- told Bloomberg. “There must be a zone country to seek a bailout, but possibility to restructure the bank- Prime Minister Jyrki Katainen and Finance Minister Jutta Urpilainen face criticism markets have not been reassured. ing sector, because it doesn’t make from opposition parties over any participation in bailing out Spanish banks. Samba! Carnaval comes to town, and Finnish politicians have begun ar- sense to recapitalise banks which samba schools from all over the guing about whether Finland should are not capable of running.” nen announced that Finland will ty chairman, Juha Sipilä, suggest- country compete over who puts participate in a bailout, and if so, if it Investors have been unenthusi- seek collateral from Spain if the ed that Spain should rescue its own on the biggest spectacle! should receive collateral. astic. Spanish bond prices fell as in- temporary bailout fund is used, be- banks, much as Finland did during Over the weekend Spain an- vestors were eager to sell, and yields cause it does not have preferred the 1990s crisis. -

Kids Eat Free!!

DAY NIGHT IS PRIME TIME!! Served with baked Idaho potato KIDS EAT FREE!! & corn on the cob EVERYDAY! Snow Crab ,<£>.. Grouper Open Mon - Sat @11 am Sunday 9:00am 2330 Palm Ridge Rd. Sanibel Island With the Purchase of One *15* and up Adult Entree «. ^»m »n tho ^w You Receive One Kids Meal lor Children 10 ft under 37 items on the "Consider the Kids" menu. Not good with any other promotion or discount. All specials subject to availability. This promotion good through February 12,2006 and subject to change at any time. Sunday 9:00-12:00 noon Master Card, Visa, Discover Credit Cards Accepted No Holidays. Must present ad. 2 • Week of February 3 - 9, 2006 ISLANDER Edith Levy -100 years young and "Aged to Perfection" BY NANCY SANTEUSANIO Special to The Islander Edith Levy is an extraordinary and elegant lady whose son and daughter Ann Wexler and Bob Levy, seven grand- children and six greal-grandchildren were ALL planners and participants in Edith's "Aged to Perfection" Birthday Parly with over 85 guests celebrating her 100th Forever Young on 19 January 2006. Proudly Ann interjects. •'The whole fami- ly was here — all 20 of us." The one point Mrs. Levy emphasizes continually with her grandchildren and great-grandchildren is "never call me 'grandma' or 'grandmother." I'm Edie.'" The motif for the party highlighted the "Aged to f •'"*• I, Perfection" theme in plates, napkins, balloons and banner. In order to avoid making this an overwhelming event for Mrs. Levy, much of the festivity was simultaneously being celebrated next door at the home of Arlene and Bob Le\ y. -

Maternal Representation in Reality Television: Critiquing New Momism in Tlc’S Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and Jon & Kate Plus 8

MATERNAL REPRESENTATION IN REALITY TELEVISION: CRITIQUING NEW MOMISM IN TLC’S HERE COMES HONEY BOO BOO AND JON & KATE PLUS 8 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Isabel Silva, B.A. Washington, DC March 24, 2014 Copyright 2014 by Isabel Silva All Rights Reserved ii MATERNAL REPRESENTATION IN REALITY TELEVISION: CRITIQUING NEW MOMISM IN TLC’S HERE COMES HONEY BOO BOO AND JON & KATE PLUS 8 Isabel Silva, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Pamela A. Fox , Ph.D . ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways that TLC’s reality programs, specifically Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and Jon and Kate Plus Eight, serve as hegemonic systems for the perpetuation of what Susan Douglas and Meredith Michaels call “new momism.” As these authors demonstrate in The Mommy Myth, the media have served as a powerful hegemonic force in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for the construction of this dominating ideology of proper motherhood which undermines the social victories of feminism. Expanding upon Douglas’ and Michaels’ analysis of national constructions of motherhood, I explore the role of reality television, a relatively new cultural medium, within the historical tradition of hegemonic institutions. My research examines representations of motherhood specifically within reality programs which document a family’s day- to-day life, differing from other types of reality shows because they take place within the private sphere of the home. These programs market performances of motherhood that invite viewers, specifically those who are mothers themselves, to construct their own identities in opposition to “transgressive” mothers and in awe of “ideal” mothers, thereby reaffirming the oppressive and unreasonable expectations of twenty-first century motherhood. -

A CUT ABOVE the REST: NEGOTIATING a FEMININE IDENTITY THROUGH COSMETIC SURGERY MAKEOVER PROGRAMS by LISA PECOT-HEBERT (Under

A CUT ABOVE THE REST: NEGOTIATING A FEMININE IDENTITY THROUGH COSMETIC SURGERY MAKEOVER PROGRAMS by LISA PECOT-HEBERT (Under the Direction of CAROLINA ACOSTA-ALZURU) ABSTRACT This study examines the influence media texts have on the reception and consumption practices of female audiences. Specifically looking at how reality makeover programming plays a role in the way women identify with socially constructed beauty ideals and incorporate them into their own lives. Through a textual analysis of The Swan and Extreme Makeover and in-depth interviews with women who have and have not had plastic surgery, this dissertation examines the power of “transformation” and how makeover programs have contributed to the normalization of cosmetic surgery as a way to create a “feminine” appearance. In addition, this dissertation argues that makeover programs provide its participants with a fairy tale experience, complete with a happy ending, which equates to shapely legs, fuller breasts and thinner noses. INDEX WORDS: Reality television, makeover programs, beauty, body image, The Swan, Extreme Makeover, identity, representation, audience reception A CUT ABOVE THE REST: NEGOTIATING A FEMININE IDENTITY THROUGH COSMETIC SURGERY MAKEOVER PROGRAMS by LISA PECOT-HEBERT B.A., The University of California, Berkeley, 1991 M.A., American University, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Lisa Pecot-Hébert All Rights Reserved A CUT ABOVE THE REST: NEGOTIATING A FEMININE IDENTITY THROUGH COSMETIC SURGERY MAKEOVER PROGRAMS by LISA PECOT-HEBERT Major Professor: Dr. Carolina Acosta-Alzuru Committee: Dr. -

From Tenino to Ghana

Halloween Edition Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Battle of the Swamp W.F. West to Take On Centralia in Rivalry Classic / Inside Food Stamp Increase Expires REDUCTION: Cuts Depend the American Recovery and Rein- maximum benefit, for example, will vestment Act, which raised Supple- see a reduction of $29 a month from on Income, Expenses mental Nutrition Assistance Pro- $526 to $497. By Lisa Broadt gram benefits to help people affected A single adult receiving the maxi- by the recession. [email protected] mum benefit will go from $189 to Monthly food benefits vary based $178. The federal government’s tem- on factors such as income, living ex- Pete Caster / [email protected] Households that receive help porary boost in food assistance pro- penses and the number of people in through the state-funded Food Lisa and Jerry Morris stand outside the Lewis County oice of grams ends Friday. the household. the Department of Social and Health Service in Chehalis Oct. 2. In April 2009, Congress passed A family of three receiving the please see FOOD, page Main 11 Overbay, Students Gather Books and Supplies, Sending Support Others to Headline From Tenino to Ghana ‘Men’s Night Out’ ADVICE: Prostate Cancer Survivor, Lyle Overbay and Health Experts to Share Experiences at Tuesday Forum By Kyle Spurr [email protected] Arnie Guenther, a retired Centralia banker, avoided the doctor’s office for physical checkups until last year when his wife finally convinced him to make an appointment. Guenther felt fine, but results from the checkup showed he had prostate cancer. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. I write in the context of major commentators such as Baudrillard ([1970]1998), Jameson (1991), and Featherstone (1991), who regard the prominence of both mediation and consumption as key to understanding contemporary or postmod- ern society. 2. Andrejevic links these trends to another form of convergence, that between leisure, labor, and consumption (2004, 53). This third conflation, while significant, is not my primary focus. 3. For simplicity’s sake, I still employ the terms “television,” “broadcast,” and “air” to refer to the primary source for the material I am discussing, even though much of it is delivered digitally via cable or satellite and distributed in a more heterogeneous fashion than in the network era. 4. I will use “public relations” or “PR” as singular nouns. 5. Indeed, Baudrillard (1996) goes one further when he credits Disney with being the precursor of a recently begun process of turning all of real life into a giant reality show. 6. Perhaps not surprisingly, this has been my own experience on several occasions, but I have also heard others say it both in real life and on television. 7. Cinema Verite (2011) is a dramatized behind-the-scenes account of the PBS series An American Family, in many ways the most obvious forerunner of today’s reality TV. 8. In 2011, US campaigns for Kraft mayo and Febreze fabric spray adopted RTV narratives and aesthetics. 9. Technologies of the self are, in Foucault’s terms, the ways in which individuals experience, understand, judge, and conduct themselves. Chapter 1 1. In 2010, the US expenditure on advertising was $131 billion and global spending on advertising is projected to exceed $500 billion in 2011.