Introduction Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic News Staff Writer EXETER | for the Average Muggle, the Activities of Friday Evening Must Have Seemed Strange

INSIDE: TV ListinGS 26,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 Vol. 33 | No. 31 | 2 Sections |32 Pages Cyan Magenta Area witches and wizards gather for book release Yellow BY SCOTT E. KINNEY ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER EXETER | For the average Muggle, the activities of Friday evening must have seemed strange. Black Witches and wizards of all ages gathered in down- town Exeter on Friday night anxiously awaiting the arrival of the seventh and final installment of the J.K. Rowling series, “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal- lows.” Hundreds of wand-wielding magicians flooded Water Street awaiting the stroke of midnight when they would be among the first to purchase the book. Two hours prior to Water Street Bookstore opening its doors, those in attendance were treated to a variety of entertainment including “Out-Fox Mrs. Weasley,” “Divine Divinations with Professor Trelawney,” “Olli- vanders Wand Shop,” “Advanced Potion Making,” “Quidditch World Cup,” and “The Great Hogwarts Hunt.” POTTER Continued on 14A• Obama courts votes in Hampton 2002 SATURN BY LIZ PREMO as well as David O’Connor, SC2 COUPE ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER principal of Marston School Auto, Leather, Sunroof, HAMPTON | A spirited where the candidate held a 63K Mi, Mint! basketball game at Hampton town hall meeting an hour #X1511P Academy was the precursor or so later. for last Friday’s energized According to campaign ONLY campaign stop in Hampton staffers, approximately 600 $ SERVICE by Democratic presidential people were in attendance 7,995 AND SALES candidate -

Wednesday Morning, Nov. 7

WEDNESDAY MORNING, NOV. 7 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Actress Debi Mazar. (N) Live! With Kelly and Michael (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) (TV14) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Money; steals and deals; Ree Drummond. (N) (cc) The Jeff Probst Show (cc) (TV14) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street The Camouflage Daniel Tiger’s Sid the Science WordWorld (TVY) Barney & Friends 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Club. (cc) (TVY) Neighborhood Kid (cc) (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Better (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol Vaca- Pearlie (TVY7) 22/KPXG 5 5 tion. (TVY) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Joseph Prince This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Alive With Kong Billy Graham: God’s Ambassador Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today With Mari- 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Scenes (cc) James Robison lyn & Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) The Bill Cunningham Show Scandal- Jerry Springer Sisters confess to The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) 32/KRCW 3 3 ous Sex Affairs. -

Shaping Embodiment in the Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture

SHAPING EMBODIMENT IN THE SWAN: FAN AND BLOG DISCOURSES IN MAKEOVER CULTURE by Beth Ann Pentney M.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2003 B.A. (Hons.), Laurentian University, 2002 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Beth Ann Pentney 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Beth Ann Pentney Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Shaping Embodiment in The Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lara Campbell Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Helen Hok-Sze Leung Senior Supervisor Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Mary Lynn Stewart Supervisor Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Zoë Druick Internal Examiner Associate Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Cressida Heyes External Examiner Professor, Philosophy University of Alberta Date Defended/Approved: ______________________________________ ii Partial Copyright Licence Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. -

State Hits Brakes on Election Canvass [email protected]

FOOTBALL DANCE WHITEVILLE AND SOUTH THIRD ANNUAL COLUMBUS COLUMBUS ADVANCE IN COUNTY DANCE FESTIVAL STATE PLAYOFFS WAS TUESDAY uu SPORTS 1B uu FESTIVAL 10A The News Reporter Published since 1890 every Monday and Thursday for the County of Columbus and her people. WWW.NRCOLUMBUS.COM Monday, November 21, 2016 75 CENTS Impact heavy on FB budget By Allen Turner [email protected] The severe damage to Fair Bluff’s res- idential areas and business district from Hurricane Matthew is still being assessed, but what’s also coming to light is the poten- tial heavy negative fiscal impact on town government. Towns rely on a number of sources of revenue, not the least of which are property taxes. With the business district essentially destroyed and a number of homes uninhab- itable, the valuation of properties will surely fall. In addition to property taxes, municipali- ties also get a percentage of state sales taxes. With business like Fair Bluff Ford and Ellis Meares closed for the foreseeable future, those revenues counted on in the current budget will be lost. uu FAIR BLUFF 9A ‘Alternative Photo by Keith Rogers This bluebird got a bird’s eye view of a deer hunter when he landed on the business end of this deer rifle on a fog-shrouded morning. proposal’ on school agenda By Allen Turner State hits brakes on election canvass [email protected] By Jefferson Weaver Tonight (Monday), the Columbus county [email protected] Board of Commissioners will hear a proposal from a firm that designs, builds, and manages An unknown number of provisional ballots school buildings to be leased by local systems. -

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr

Celebrity Interview: ‘Botched’ Star Dr. Paul Nassif Discusses Being Single, Skincare and Spin-Off Shows Interview by Lori Bizzoco. Written by Stephanie Sacco. Dr. Paul Nassif is more than a doctor on reality TV. He’s a renowned facial plastic surgeon and skincare specialist. Though people may remember him from The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, he’s even more recognizable for his E! reality series, Botched which he co-hosts with former RHOC star, Dr. Terry Dubrow. The success of Botched has even led to a few upcoming spin-off shows, Botched By Nature and Botched Post- Op. Last week, Nassif spoke to us in an exclusive celebrity interview about the upcoming spin-off shows, his new anti- aging skincare line and his very single relationship status. Reality TV Star Dr. Paul Nassif Talks ‘Botched’ Success Back when Nassif first developed the concept for Botched and pitched the show, his co-host was doubtful, calling Nassif “crazy” for wanting to put plastic surgery on TV. “Now look at us,” the former RHOBH star says. Botched is in its third season and the show has led to multiple spin-off series. One of the many reasons for the show’s success is that all the cases are legitimate, and Nassif and Dubrow are passionate about their clients. The doctors really enjoy helping their patients through their issues. Nassif says the role of a plastic surgeon is “part doctor and part therapist.” Although extreme cases are common in this line of work, the reality TV star shares that the worst is yet to come. -

Atlantic News Courtesy Photo — 44 in CONCERT O Milk Money (1994) Melanie Griffith

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 26 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 26A | ATLANTIC NEWS | NOVEMBER 4, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 44 SEACOAST ENTERTAINMENT &ARTS | ATLANTICNEWS.COM . NOTES ANNUAL CRAFT, 11/9/05 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 FOOD FAIR AMONG THE BEST WBZ-4 Dr. Phil (N) News CBS The Insid- Ent. Still Yes, Dear Criminal Minds “The CSI: NY “Manhattan News Late Show With Late Late SALEM | The 10th annual New (CBS) (CC) News er (N) Tonight Standing (N) Fox” (N) (CC) Manhunt” (N) (CC) (CC) David Letterman (N) Show England Craft and Specialty Food WCVB-5 News News News ABC Wld Inside Chronicle George Freddie Lost “Abandoned” Invasion “Fish Sto- News (:35) (12:06) Jimmy Kim- (ABC) (CC) (CC) (CC) News Edition (CC) Lopez (N) (N) (CC) (N) ’ (HD) (CC) ry” (N) (CC) (CC) Nightline mel Live (N) ’ Fair will be held indoors at the Rock- WCSH-6 News ’ News ’ News ’ NBC 207 Maga- Seinfeld E-Ring “Cemetery The Apprentice: Law & Order “House News ’ The Tonight Show Late Night ingham Park Racetrack in Salem on (CBS) (CC) (CC) (CC) News zine ’ (CC) Wind” (N) (CC) Martha Stewart (N) of Cards” (CC) With Jay Leno (N) Friday through Sunday, November WHDH-7 News ’ News ’ News ’ NBC Access Extra (N) E-Ring “Cemetery The Apprentice: Law & Order “House News ’ The Tonight Show Late Night 11-13, from 10 a.m. -

Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS ___________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of MissouriColumbia ______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ by KRISTIN L. CHERRY Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Cherry 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS presented by Kristin L. Cherry, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Michael Porter Professor Jon Hess Professor Mary Jeanette Smythe Professor Joan Hermsen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Jennifer Stevens Aubrey for her direction on this dissertation. She spent many hours providing comments on earlier drafts of this research. She always made time for me, and spent countless hours with me in her office discussing my project. I would also like to thank Michael Porter, Jon Hess, Joan Hermsen, and MJ Smythe. These committee members were very encouraging and helpful along the process. I would especially like to thank them for their helpful suggestions during defense meetings. Also, a special thanks to my fiancé Brad for his understanding and support. Finally, I would like to thank my parents who have been very supportive every step of the way. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..ii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..…….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………….……v ABSTRACT………………………………………………………….…………………vii Chapter 1. -

P32 Layout 1

MONDAY, JUNE 15, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 12:05 E! News 18:00 Cristela 13:05 Eric And Jessie: Game On 18:30 Mulaney 13:35 Eric And Jessie: Game On 19:00 About A Boy 14:05 Extreme Close-Up 19:30 Cougar Town 14:30 Style Star 20:00 Last Man Standing 00:40 Bargain Hunt 15:00 Kourtney And Khloe Take 20:30 The Goldbergs 02:00 My Piece Of The Pie 01:25 Bargain Hunt The Hamptons 21:00 The Daily Show With Jon 04:00 Scents And Sensibility 02:10 Extreme Makeover: Home 16:00 Kourtney And Khloe Take Stewart 05:30 Hateship Loveship Edition Specials The Hamptons 21:30 Last Week Tonight With John 07:15 Annie 03:30 Come Dine With Me 17:00 Christina Milian Turned Up Oliver 09:30 The Joy Luck Club 03:55 Come Dine With Me 17:30 Christina Milian Turned Up 22:05 Veep 12:00 Up Close And Personal 04:20 Come Dine With Me 18:00 E! News 22:30 Silicon Valley 14:30 The Damned United 04:45 Come Dine With Me 19:00 Keeping Up With The 23:00 Jonah From Tonga 16:30 The Joy Luck Club 05:15 Come Dine With Me Kardashians 23:30 Last Man Standing 19:00 Australia 05:40 New Scandinavian Cooking 20:00 House Of DVF 22:00 To The Wonder 06:05 Come Dine With Me: South 21:00 Fashion Bloggers Africa 21:30 Fashion Bloggers 07:00 Bargain Hunt 22:00 New Money 07:45 Come Dine With Me 22:30 New Money 00:00 Top Gear (UK) 08:10 Antiques Roadshow 23:00 E!ES 01:15 The Immigrant-PG15 01:00 Tyrant 03:15 Need For Speed-PG15 09:05 Bargain Hunt 02:00 Olive Kitteridge 09:50 Come Dine With Me 05:30 Planes: Fire And Rescue-PG 03:00 Banshee 07:00 Streetdance: All Stars-PG15 10:15 Come Dine With Me 04:00 Scandal -

Hy-Vee MEAT DEPARTMENT Means

FRIDAY ** AFTERNOON ** FEBRUARY 27 THURSDAY ** AFTERNOON ** MARCH 5 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Assignment: The Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘My Music WordGirl Dr. Two The Electric Cyberchase Wishbone ‘‘Bark to Nightly Business KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Design Squad ‘‘No Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘Fern’s WordGirl Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase ‘‘True Wishbone ‘‘The Nightly Business Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood Bears (S) (S) (EI) World ‘‘Show Way’’ Rules.’’ (S) (EI) Brains threatens. Company (S) (EI) ‘‘Crystal Clear’’ the Future’’ (S) Report (N) (S) Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood (S) Bears (S) Chasing a pickle. Crying in Baseball’’ ‘‘Best Friends.’’ Slumber Party.’’ WordGirl’s identity. Ruffman (S) (EI) Colors’’ (S) (EI) Count’s Account’’ Report (N) (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show Rosie O’Donnell; Little House on the Prairie ‘‘No Beast Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show Actor News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News KTIV f X News (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘A Promise Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show ‘‘The News NBC Nightly News Ruby Dee. (N) (S) So Fierce’’ David Arquette. -

P32 Layout 1

THURSDAY, JULY 2, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 14:20 Railroad Alaska 09:00 Barefoot Contessa - Back To Stewart 15:10 Overhaulin’ 2012 Basics 16:00 The Nightly Show With Larry 16:00 Fast N’ Loud 10:00 The Kitchen Wilmore 16:50 How It’s Made 11:00 The Big Eat... 16:30 My Boys 17:15 How Do They Do It? 12:00 Chopped 17:00 Late Night With Seth Meyers 00:25 Doctors 17:40 Bear Grylls: Breaking Point 13:00 Guy’s Big Bite 18:00 Galavant 00:50 Eastenders 18:30 King Of Thrones 14:00 Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives 18:30 The Goldbergs 01:20 Spooks 19:20 Tanked 15:00 Man Fire Food 19:00 Two And A Half Men 02:15 Stella 20:10 Extreme Collectors 16:00 Chopped 19:30 Community 03:00 Starlings 20:35 Auction Kings 17:00 The Kitchen 20:00 The Tonight Show Starring 03:45 The Office 21:00 King Of Thrones 18:00 Barefoot Contessa - Back To Jimmy Fallon 04:15 The Weakest Link 21:50 Insane Pools: Off The Deep Basics 21:00 The Daily Show With Jon 05:00 The Green Balloon Club End 19:00 Chopped Stewart 05:25 Mr Bloom’s Nursery 22:40 Tanked 20:00 Iron Chef America 21:30 The Nightly Show With Larry 05:45 Show Me Show Me 23:30 Street Outlaws 21:00 Trisha’s Southern Kitchen Wilmore 06:10 Nuzzle & Scratch: Frock n 22:00 Farm King 22:00 Modern Family Roll 23:00 Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives 22:30 Black-Ish 06:30 The Green Balloon Club 23:00 The Simpsons 06:50 Mr Bloom’s Nursery 23:30 Late Night With Seth Meyers 07:15 The Weakest Link 08:00 The Office 08:30 Doctors 00:00 Violetta 09:00 Eastenders 00:50 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 09:30 The Paradise 00:10 The Chase Teenage Witch 01:05 Paddock To Plate -

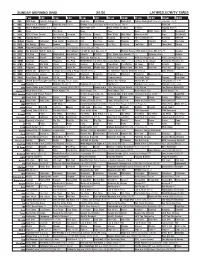

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Need-See Bull Riding Basketball College Basketball Xavier at Georgetown. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at New York Rangers. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Flipping Houses 7 ABC News This Week News News News ABC7 Game NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Help Now! Women on the Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Flipping Houses Fox News Sunday News The Issue Flipping Paid Prog. PBC Countdown (N) RaceDay NASCAR 1 3 MyNet Flipping Concealer Fred Jordan Freethought AAA Paid Prog. Secrets Flipping AAA Flipping News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Get Energy Smile Income AAA Paid Prog. Hempvana Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Foot Pain AAA Toned Abs Omega 2 2 KWHY Programa pagado Programa que muestra diversos productos para la venta. (6) (TVG) 2 4 KVCR The Keto Diet With Dr. Josh Axe The Collagen Diet with Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Å Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Sesame 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Wunderkind Wunderkind Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Elvis, Aloha From Hawaii (TVG) Å Relieving Stress Antoine 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid Prog. -

Kids Eat Free!!

DAY NIGHT IS PRIME TIME!! Served with baked Idaho potato KIDS EAT FREE!! & corn on the cob EVERYDAY! Snow Crab ,<£>.. Grouper Open Mon - Sat @11 am Sunday 9:00am 2330 Palm Ridge Rd. Sanibel Island With the Purchase of One *15* and up Adult Entree «. ^»m »n tho ^w You Receive One Kids Meal lor Children 10 ft under 37 items on the "Consider the Kids" menu. Not good with any other promotion or discount. All specials subject to availability. This promotion good through February 12,2006 and subject to change at any time. Sunday 9:00-12:00 noon Master Card, Visa, Discover Credit Cards Accepted No Holidays. Must present ad. 2 • Week of February 3 - 9, 2006 ISLANDER Edith Levy -100 years young and "Aged to Perfection" BY NANCY SANTEUSANIO Special to The Islander Edith Levy is an extraordinary and elegant lady whose son and daughter Ann Wexler and Bob Levy, seven grand- children and six greal-grandchildren were ALL planners and participants in Edith's "Aged to Perfection" Birthday Parly with over 85 guests celebrating her 100th Forever Young on 19 January 2006. Proudly Ann interjects. •'The whole fami- ly was here — all 20 of us." The one point Mrs. Levy emphasizes continually with her grandchildren and great-grandchildren is "never call me 'grandma' or 'grandmother." I'm Edie.'" The motif for the party highlighted the "Aged to f •'"*• I, Perfection" theme in plates, napkins, balloons and banner. In order to avoid making this an overwhelming event for Mrs. Levy, much of the festivity was simultaneously being celebrated next door at the home of Arlene and Bob Le\ y.