"Baby, I Wish We Could Get You Some Lips for Christmas": Investigating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One and Only

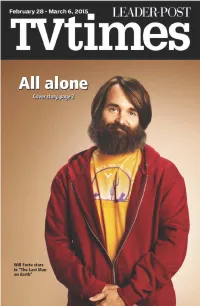

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

COOKBOOK for a CAUSE Volume 2

COOKBOOK FOR A CAUSE volume 2 TLC’S STARS SHARE FAVORITE RECIPES TO BENEFIT FEEDING AMERICA® FIGHTING HUNGER IN AMERICA ONE COOKBOOK at A TIME. The Pampered Chef® Cookbook for a Cause, Volume 2 benefits Feeding America®, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. This year, the popular television network TLC® joined our mission to help fight hunger. TLC® stars from Cake Boss, Say Yes to the Dress, DC Cupcakes, The Little Couple, 19 Kids and Counting, What Not To Wear, and more, generously contributed their favorite recipes, in their own words. For each cookbook sold, we’ll donate $1 to Feeding America® to help provide eight meals to those in need.* We hope you’ll enjoy these recipes from the TLC® stars and the helpful tips and techniques from the experts in The Pampered Chef® Test Kitchens. As you gather around the table with family and friends, you can feel good that you’re helping another family in need to do the same. The Pampered Chef® The Pampered Chef® is the largest direct seller of everything you need to cook and entertain at home. At in-home Cooking Shows, guests see and try products, prepare and sample recipes, and learn quick and easy food preparation techniques and tips on how to entertain with style and ease — transforming the everyday into the extraordinary. TLC® is all about real-life reality, transporting the viewers into the lives of real-life extraordinary people with character. TLC® programs are entertaining, unfiltered and always reveal something worthwhile. TLC® is curious about people and finding the extraordinary in the everyday. -

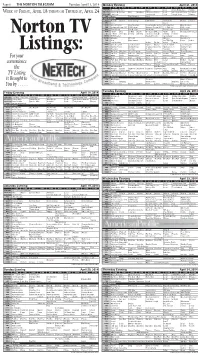

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

Wednesday Morning, Nov. 7

WEDNESDAY MORNING, NOV. 7 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Actress Debi Mazar. (N) Live! With Kelly and Michael (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) (TV14) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Money; steals and deals; Ree Drummond. (N) (cc) The Jeff Probst Show (cc) (TV14) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street The Camouflage Daniel Tiger’s Sid the Science WordWorld (TVY) Barney & Friends 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Club. (cc) (TVY) Neighborhood Kid (cc) (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Better (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol Vaca- Pearlie (TVY7) 22/KPXG 5 5 tion. (TVY) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Joseph Prince This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Alive With Kong Billy Graham: God’s Ambassador Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today With Mari- 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Scenes (cc) James Robison lyn & Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) The Bill Cunningham Show Scandal- Jerry Springer Sisters confess to The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) 32/KRCW 3 3 ous Sex Affairs. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Jobs Rally Goes Off As Planned

A1 Vol. 131, Issue 249 .50 INDEX Obits ... page 3 Opinions ... page 4 Business ... page 5 Sports ... page 6 Classifieds ... page 7 Scattered Showers Serving Surry County since 1880. High Low Braves take Dodgers Page 6 Forsubscriptions, call 786-4141. 70 61 The Mount Airy News www.mtairynews.com Printed on recycled newspaper Tuesday, September 6, 2011 Weekend event to celebrate agriculture Staff Report DOBSON — The sixth annual Celebrating Agricul- ture festival will take place this Saturday at Fisher River Park. The festival, put on each year by the Surry County Cooperative Extension, is designed to provide a chance for families to learn more about agriculture and farming and its role in daily life. “It’s going to be awe- some. I’m so excited about it,” said Joanna Radford, extension agent who is orga- nizing the event. Once again there will be plenty of activities for children during the event including rides, games and other activities. There will be a 4-H activity area for kids and a train ride made of barrels to take kids around MORGAN WALL/THE NEWS the park. Kids will even be Mount Airy Mayor Deborah Cochran, along with Surry County Board of Commissioner Chairman Paul Johnson, Mount Airy City Com- able to visit a chicken coop missioner Steve Yokeley, Mount Airy City Commisioner Todd Harris and Mount Airy City Commissioner Dean Brown, address the crowd and help collect eggs. There also will be bounce houses gathered for Monday evening’s jobs rally. for kids. Antique, classic and new tractors will be on display and local craftsmen and farmers will be putting on Jobs rally goes a blacksmithing demonstra- tion and making corn meal. -

P32 Layout 1

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 06:00 Lolirock 16:30 Home Fires 14:00 Perception 06:25 Hank Zipzer 17:25 The Widower 15:00 Glee 06:50 Girl Meets World 18:20 The Chase: Celebrity Special 16:00 Emmerdale 07:15 H2O: Just Add Water 19:10 Coronation Street 16:30 Coronation Street 07:40 Jessie 19:35 The Chase 17:00 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 00:20 Come Dine With Me 08:05 Wizards Of Waverly Place 20:30 Home Fires 18:00 Perception 01:10 MasterChef 08:30 Wizards Of Waverly Place 21:25 The Widower 19:00 Criminal Minds 02:00 Antiques Roadshow 08:55 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 22:20 Coronation Street 20:00 Bones 02:55 Come Dine With Me Teenage Witch 22:50 Emmerdale 21:00 Chicago Fire 03:20 Lorraine’s Fast, Fresh And 09:20 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 23:15 The Chase: Celebrity Special 22:00 The Americans Easy Food Teenage Witch 23:00 Mistresses 03:45 New Scandinavian Cooking 09:45 Austin & Ally 04:10 Antiques Roadshow 10:10 Austin & Ally 05:05 Masterchef: The 10:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place Professionals 11:00 Wizards Of Waverly Place 05:30 New Scandinavian Cooking 11:25 Jessie 00:20 Deadly Super Cat 05:55 Lorraine’s Fast, Fresh And 11:50 Jessie 01:10 The Living Edens Easy Food 12:15 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 02:00 Speed Kills 06:25 Come Dine With Me 02:50 Dangerous Encounters Teenage Witch 01:00 Good Morning America 06:50 Antiques Roadshow 12:40 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 03:45 Monster Fish 07:40 Come Dine With Me 04:40 How Big Can It Get 03:00 Better Call Saul Teenage Witch 04:00 Salem 08:05 Antiques Roadshow 13:05 Good Luck Charlie 05:35 Speed Kills 09:00 Ty Pennington’s Homes For 06:30 Dangerous Encounters 05:00 Good Morning America 13:30 Good Luck Charlie 07:00 Emmerdale The Brave 13:55 Dog With A Blog 07:25 Monster Fish 09:45 Come Dine With Me 08:20 The Lion Ranger 07:30 Coronation Street 14:20 H2O: Just Add Water 09:00 Suits 10:35 MasterChef 14:55 Lolirock 09:15 Unlikely Animal Friends 11:25 Antiques Roadshow 10:10 Dr. -

Atlantic News Courtesy Photo — 44 in CONCERT O Milk Money (1994) Melanie Griffith

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 26 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 26A | ATLANTIC NEWS | NOVEMBER 4, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 44 SEACOAST ENTERTAINMENT &ARTS | ATLANTICNEWS.COM . NOTES ANNUAL CRAFT, 11/9/05 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 FOOD FAIR AMONG THE BEST WBZ-4 Dr. Phil (N) News CBS The Insid- Ent. Still Yes, Dear Criminal Minds “The CSI: NY “Manhattan News Late Show With Late Late SALEM | The 10th annual New (CBS) (CC) News er (N) Tonight Standing (N) Fox” (N) (CC) Manhunt” (N) (CC) (CC) David Letterman (N) Show England Craft and Specialty Food WCVB-5 News News News ABC Wld Inside Chronicle George Freddie Lost “Abandoned” Invasion “Fish Sto- News (:35) (12:06) Jimmy Kim- (ABC) (CC) (CC) (CC) News Edition (CC) Lopez (N) (N) (CC) (N) ’ (HD) (CC) ry” (N) (CC) (CC) Nightline mel Live (N) ’ Fair will be held indoors at the Rock- WCSH-6 News ’ News ’ News ’ NBC 207 Maga- Seinfeld E-Ring “Cemetery The Apprentice: Law & Order “House News ’ The Tonight Show Late Night ingham Park Racetrack in Salem on (CBS) (CC) (CC) (CC) News zine ’ (CC) Wind” (N) (CC) Martha Stewart (N) of Cards” (CC) With Jay Leno (N) Friday through Sunday, November WHDH-7 News ’ News ’ News ’ NBC Access Extra (N) E-Ring “Cemetery The Apprentice: Law & Order “House News ’ The Tonight Show Late Night 11-13, from 10 a.m. -

Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS ___________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of MissouriColumbia ______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________________ by KRISTIN L. CHERRY Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Cherry 2008 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REALITY TV AND INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP PERCEPTIONS presented by Kristin L. Cherry, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Michael Porter Professor Jon Hess Professor Mary Jeanette Smythe Professor Joan Hermsen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my committee members for their helpful suggestions and comments. First, I would like to thank Jennifer Stevens Aubrey for her direction on this dissertation. She spent many hours providing comments on earlier drafts of this research. She always made time for me, and spent countless hours with me in her office discussing my project. I would also like to thank Michael Porter, Jon Hess, Joan Hermsen, and MJ Smythe. These committee members were very encouraging and helpful along the process. I would especially like to thank them for their helpful suggestions during defense meetings. Also, a special thanks to my fiancé Brad for his understanding and support. Finally, I would like to thank my parents who have been very supportive every step of the way. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..ii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..…….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………….……v ABSTRACT………………………………………………………….…………………vii Chapter 1. -

Updates to the Animoca Brands Game Portfolio Acquisition and Masterchef: Dream Plate

iCandy Interactive Limited (ACN 604 871712) Level 4, 91 William Street Melbourne, VIC 3000 Australia 4 June 2020 ASX and Media Announcement Updates to the Animoca Brands Game Portfolio Acquisition and MasterChef: Dream Plate Highlights ● All technical matters in the operational handover process of the game portfolio acquired from Animoca Brands have been resolved ● In a show of confidence on the prospects of iCandy, Animoca Brands agrees to receive shares of iCandy as settlement for all outstanding consideration for the acquisition of the game portfolio of Animoca Brands ● A total 30,208,415 new shares in iCandy will be issued to Animoca Brands with an issue price of A$0.0206 each (15-days VWAP) ● Animoca Brands’ shareholding in iCandy will increase from 7.9% to 15.5% of total shares ● Animoca Brands and iCandy agree to work closely together on future collaboration opportunities ● MasterChef: Dream Plate, a game jointly developed by iCandy, Animoca Brands in partnership with Endemol Shine North America, has launched with approximately 500,000 pre-orders and pre-registration Updates To The Animoca Brands Game Portfolio Acquisition iCandy Interactive Limited (ASX: ICI) (“iCandy”, the “Company”) is pleased to provide an update on the status of the acquisition of Animoca Brands Limited’s (“Animoca Brands”) casual game portfolio, which was originally announced on 15 November 2017. As previously announced on 11 April 2019, although iCandy acquired the ownership and legal rights of the game portfolio from Animoca Brands, there were outstanding technical matters in the operational handover process in which certain software source code of some mobile games of lesser importance had not been transferred from Animoca Brands to iCandy. -

Hy-Vee MEAT DEPARTMENT Means

FRIDAY ** AFTERNOON ** FEBRUARY 27 THURSDAY ** AFTERNOON ** MARCH 5 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Assignment: The Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘My Music WordGirl Dr. Two The Electric Cyberchase Wishbone ‘‘Bark to Nightly Business KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Design Squad ‘‘No Reading Rainbow Arthur ‘‘Fern’s WordGirl Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase ‘‘True Wishbone ‘‘The Nightly Business Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood Bears (S) (S) (EI) World ‘‘Show Way’’ Rules.’’ (S) (EI) Brains threatens. Company (S) (EI) ‘‘Crystal Clear’’ the Future’’ (S) Report (N) (S) Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood (S) Bears (S) Chasing a pickle. Crying in Baseball’’ ‘‘Best Friends.’’ Slumber Party.’’ WordGirl’s identity. Ruffman (S) (EI) Colors’’ (S) (EI) Count’s Account’’ Report (N) (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show Rosie O’Donnell; Little House on the Prairie ‘‘No Beast Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show Actor News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News KTIV f X News (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘A Promise Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show ‘‘The News NBC Nightly News Ruby Dee. (N) (S) So Fierce’’ David Arquette. -

Battle of Iwo Jima Remembered at Eco Park Ceremony

NOW THREE DAYS A WEEK POST COMMENTS AT CAPE-CORAL-DAILY-BREEZE.COM Eagles CAPE CORAL in action Both FGCU basketball teams take to the court BREEZE — SPORTS EARLY-WEEK EDITION WEATHER: Mostly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Wednesday: Mostly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 50, No. 23 Tuesday, February 22, 2011 50 cents Southwest Florida & Lee County Fair starts Friday Dog Show. 87th annual event to feature new rides, shows and exhibits, with returning favorites Executive producer Chris the By ANDREA GALABINSKI through Sunday, March 6, at the counties from 4-H and Future the Del Prados. “Stunt Dog Guy” Perondi is the [email protected] Lee Civic Center. Farmers of America and other Concerning shows for all ages, organizer of the Extreme Canine You can come with the family “Moonlight Madness” nights participants. the popular kid favorites Kandu Stunt Show. “We’ve been travel- all day, or take part in Moonlight this year are Friday, Feb. 25, and There will be the standard & Co. Magic Show and Tadpole ing nationwide and will do about Madness Nights, and see all the Friday, March 4. Moonlight favorites in rides along with new the Clown will be back this year, 700 shows this year, at theme animals, enjoy exhibits, great Madness goes from 10 p.m. to 2 rides. along with the Wild About parks, events and other county food, rides and music. a.m. with unlimited rides for $20. For entertainment and shows, Monkeys animal show and the fairs.” The 87th Annual Southwest Many come just to enjoy the local talent is always a favorite, Shark Encounter.