Report on the Tennis Environment in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Memo

2014 published by itf ltd bank lane roehampton 4 london sw15 5xz uk registered address: po box n-272, nassau, bahamas tel: +44 (0)20 8878 6464 fax: +44 (0)20 8878 7799 web: www.itftennis.Com itf davis Cup regulations 122 NATIONS 488 PLAYERS 1 WORLD CHAMPION SHOW YOUR COLOURS #DAVISCUP BRINGING TENNIS TO THE WORLD SINCE 1900 WWW.DAVISCUP.COM /DAVISCUP @DAVISCUP DAVISCUP CONTENTS I THE COMPETITION 1. Title 1 2. Ownership 1 3. Nations Eligible 1 4. Entries 1 5. Rules and Regulations 2 6. Trophies 3 7. Medical Control 3 II MANAGEMENT 8. Board of Directors 4 9. The Davis Cup Committee 5 10. The Davis Cup Executive Director 5 III PENALTIES AND ARBITRATION 11. Decisions 6 12. Withdrawal of a Nation 6 13. Failure to Send a Team 6 14. Failure to Abide by these Rules and Regulations 6 15. Failure to Carry out Sponsorship Requirements 7 16. Delays and Defaults in Payments and submission of Accounts 7 17. Appeal and Arbitration 7 IV DIVISION OF COMPETITION 18. The World Group 8 19. The Zonal Competitions - Participation 8 20. Americas and Asia/Oceania Zones Group I 9 21. Europe/Africa Zone Group I 10 22. Americas and Asia/Oceania Zones Group II 10 23. Europe/Africa Zone Group II 11 24. Zonal Competitions Group III and Group IV 12 V ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COMPETITION 25. The Draw 12 26. Dates for Rounds 12 27. Choice of Ground 13 28. Minimum Standards for the Organisation of Ties 14 29. General Arrangements for Ties 14 30. Arrangements for Davis Cup Final 15 31. -

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2016 (April 1, 2016 ~ March 31, 2017)

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2016 (April 1, 2016 ~ March 31, 2017) 1. Organizational Management In FY2016, the Japan Tennis Association was run based on the Meeting of the Board of Directors and the monthly Meeting of Executive Directors under the re-elected JTA President, Nobuo Kuroyanagi. However, policies were planned and executed by 25 specialized committees set up under four sectoral departments, namely High Performance, Development, Event Operations, and General/Finance, and by 12 offices established directly under the President, the Senior Executive Director, and the Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Councilors, consisting of 69 representatives of member and cooperative associations and opinion leaders, met twice in the fiscal year and passed resolutions for the FY2016 business results and financial statement as well as the FY2017 business plans and budget. JTA's business scale has expanded since becoming a public interest incorporated foundation (koueki zaidan houjin), thanks to the increasing interest in tennis by Japanese society, implementing projects to strengthen players for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and hosting tournaments. The operating organization required strengthening, which resulted in an amendment in the articles of incorporation by the Board of Councilors. The number of Directors was increased from a maximum of 30 to a maximum of 35 directors, and the number of Executive Directors was increased from 15 to 17. Committee activities expanded, which subsequently increased the workload of the JTA secretariat that supports all committee activities. In particular, during the Japan Tennis Weeks, the tournament operating headquarters and the secretariat showed perfect teamwork in the months of September and October. -

GNTC Business Plan

1 Section I | Executive Summary Page 3 Section II | Narrative Page 4 Site map Page 5 Design concept Page 5 Project Impact Page 9 Project Sustainability Page 12 Qualification & Experience Page 14 Section III | Financial Projections Page 16 2 Section I | Executive Summary Organization: Guam National Tennis Federation established 1972 Mission Guam National Tennis Federation (GNTF) intends to build a self-sustaining National Tennis Center to develop the sport of tennis and grow the sport among our local community. Primarily the facility will provide a pathway for youth to develop as tennis players. The National Tennis Center GNTF will build a National Tennis Center on land leased at the Harmon Sports Complex. Key Personnel Project will be led by GNTF board of directors, Torgun Smith President. Committee includes Ken Hsieh, Engineer; Albert Tsustui, Architect; Kim Ewart, Architect; Tom Camacho, Government Liaison; Todd Smith, businessman; Marc Adler, consultant; Benson Au-Yeng, businessman; and Duncan McCully, Attorney. Facility manager will be recruited when the project is in completion stage. For continuity of leadership, a separate foundation and board of directors will be formed to oversee management of the facility. This board will be comprised of stakeholders in the project. The Market The tennis industry has several market segments we intend to target: individual players, tennis leagues/groups, tourist groups, after school programs, camps, tournaments and events, and pro shop. These segments can be broken down by age, juniors, and adults. -

Contentsissue74

COACHING & SPORT SCIENCE REVIEW The Official Tennis Coaching and Sport Science Publication of the International Tennis Federation 26th Year, Issue 74, April 2018 www.itftennis.com/coaching/sportsscience ISSN: 2225-4757 4 CONTENTSISSUE7 Pg. Title / Author 2 Editorial 3 How do LTA mini tennis modifications shape children’s match-play performance? Anna Fitzpatrick , Keith Davids and Joseph Antony Stone (GBR) 6 Tournament planning proposal for a junior player Francisco J. Penalva (ESP) 9 Training matches in women’s tennis (Part 1) Jean-Luc Cotard (FRA) 12 Training matches in women’s tennis (Part 2) Jean-Luc Cotard (FRA) 15 The effect of a variable practice method on tennis groundstroke learning of adult beginners Sahan A., Erman KA., Ertekin E. (TUR) 18 Muscle memory and imagery: Better tennis. An introduction Archie Dan Smith (USA) 20 The inside out stroke in men´s tennis: Strategies and tactics Encarna Martín, José Campos and Miguel Crespo (ESP) 23 Tactical analysis in tennis: From its origins to the present Rafael Martínez (ESP) 25 Winning or losing in wheelchair Grand Slam tournaments Alejandro Sánchez, Antonio Ortega and David Sanz (ESP) 29 Description of the morpho- functional characteristics of junior tennis players Jorge Mauricio Celis (COL) 32 Recommended e-books Editors 33 Recommended web links Editors 34 General guidelines for submitting articles to ITF Coaching & Sport Science Review Editors COACHING & SPORT SCIENCE REVIEW The Official Coaching and Sport Science Publication of the International Tennis Federation EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 74 of the ITF Coaching and Sport Science Review, the first issue of 2018. In this issue, the topics cover a range of aspects in the game including: periodization for juniors, muscle memory and imagery, the inside out forehand, tactical/ notational analysis, adapted equipment, and winning or losing at wheelchair tennis Grand Slam tournaments, among others. -

The JOC 2016

The 6 JOC JOC ACTIVITIES CONTACT JAPANESE OLYMPIC COMMITTEE Address : KISHI MEMORIAL HALL 1-1-1 JINNAN, SHIBUYA-KU TOKYO 150-8050, JAPAN Tel : +81-3-3481-2233 Fax : +89-3-3481-0977 URL : http://www.joc.or.jp/english/ Photo by Ao Sport, AP/Ao, Reuters/Ao, PHOTO KISHIMOTO Japanese Olympic Committee 03 Message from JOC President Tsunekazu Takeda 04 History of the JOC 05 Performance-Enhancement Programs 14 Olympic Movement Programs 21 Games Participation Programs 27 Marketing and Other Programs 31 List of JOC Executives 32 Afliated National Federations 34 Summary of Financial Results 36 Compliance and Governance CONTENTS Project Performance-Enhancement Olympic Movement Programs 01 Programs 02 The participation of Japanese athletes in major The Olympic Movement is a peace movement international sports competitions, including the that promotes the noble Olympic ideals Olympic Games, inspires and brings happiness to (Olympism) to increase mutual understanding many people. In addition, this participation raises the through friendship, solidarity, and the spirit of level of interest in sports among the public, and fair play based on the Olympic Charter. The contributes greatly to popularising and promoting JOC holds a variety of events and actively Mission sports in Japan. In order to sustain the development disseminates information throughout the year of elite-level competitors able to participate in such to promote and educate people about the The JOC’s mission lies in urging all events, the JOC from time to time evaluates and Olympic Movement. people to participate in sports, cultivating improves the enhancement strategy plans proposed athletes with sound minds and bodies, by afliated national federations, and takes active and strongly promoting the Olympic measures to develop not only athletes but also Movement. -

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2018 (April 1, 2018 ~ March 31, 2019)

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2018 (April 1, 2018 ~ March 31, 2019) 1. Organizational Management The management of the association in fiscal year 2018 was led by President Nobuo Kuroyanagi, who was re-elected in the previous year, assisted by 19 Executive Directors, and using a structure of 4 Departments. Due to having an extraordinary board meeting in December, which had become customary for the last several years, we were again able to hold 3 board meetings in fiscal year 2018 and were thus able to confirm the status of the business as well as of the execution of the budget for fiscal year 2018 and get an early start on preparations for human resources for the next fiscal year as well. Furthermore, the Board of Executive Directors, consisting of the President and Executive Directors, met 11 times (every month with the exception of August). Business was conducted by the Board of Executive Directors, with the support of 35 specialized committees largely made up of volunteers assisted by our administrative staff. 69 member-Board of Councilors consisting of member organizations, supporting organizations, and this association, served as the association's highest voting body by approving the fiscal year 2018 financial statement and business report, in addition to the fiscal year 2019 business plan and budget. At the onset, the operation of our association in fiscal year 2018 faced some uncertainty, prompting us to approach the new year with caution. Our inability to use the Ariake Tennis Forest Park due to ongoing renovations in preparation for the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games led us to seek other venues to host our tournaments. -

Joc Activity 2016-2017 Joc Activity 2016-2017 2 Greetings Contents

JOC 2016 -March 2017 Publication Date October 2017 Published By Japanese Olympic Committee Editorial Design Dentsu Inc. Photos By Aflo Sport, AFP/Aflo, PHOTO KISHIMOTO CONTACT Kishi Memorial Hall, 1-1-1 Jinnan, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8050 JAPAN Japanese Olympic Committee Public Affairs & Strategic Planning Department Tel +81-3-3481-2258 Fax +81-3-3481-0977 Conceptual Diagram of the JOC’s Mission, Sharing the Power of the Olympics Roles, and Activities The Olympic Games have taught us We encourage all people to participate in sports, that passion touches the heart more than glory. nurture athletes with sound minds and bodies, and strongly promote the Olympic Movement. That humanity is united by something Mission Through the Olympic Movement,we allow humankind to transcending language and borders. flourish, to elevate culture, and to keep the flame of world peace alight forevermore. Olympians have shown us These are the ideals and the overall mission of the JOC. that mutual respect makes all medals equally valuable. It is true that the Olympic Games have power. - Developing and Strengthening Athletes The power to change people and society for the better. Through sports, develop young people of integrity who embody Olympism, and value to society. By supporting Olympians, we want to share such power with the world. - Sending Athletes to International Multi-Sports Roles Competitions and Promoting Internationalization This is our mission. Through interaction between international sports organizations and international multi-sports competitions, deepen mutual understanding and promote peace and friendship. The Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC) - Disseminating and Promoting Olympism Promote the Olympic Movement, emphasize the value of sports, and work to disseminate Olympism. -

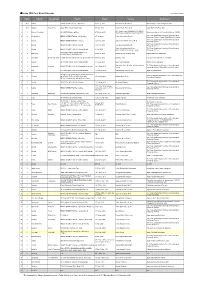

Tokyo 2020 Test Event Calendar As of March 8, 2019

◆Tokyo 2020 Test Event Calendar As of March 8, 2019 No Wave Sports Disciplines Events Dates Venues Organisers 1 2018 Sailing Sailing's World Cup Series Enoshima 9-16 Sep. 2018 Enoshima Yacht Harbour World Sailing / Japan Sailing Federation 2 2018 Aquatics Water Polo Japan Swimming Championships 5-7 Oct. 2018 Tatsumi Water Polo Centre Japan Swimming Federation AGF Field(Current AJINOMOTO STADIUM 3 1 Modern Pentathlon 2019 UIPM World Cup Final 27-30 Jun. 2019 Union Internationale de Pentathlon Moderne (UIPM) West Field) / Musashino Forest Sport Plaza The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic & 4 1 Weightlifting READY STEADY TOKYO - Weightlifting 6-7 Jul. 2019 Tokyo International Forum Paralympic Games / Japan Weightlifting Association The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic & 5 1 Archery READY STEADY TOKYO - Archery 12-18 Jul. 2019 Yumenoshima Park Archery Field Paralympic Games The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic & 6 1 Surfing READY STEADY TOKYO - Surfing 18-21 Jul. 2019 Tsurigasaki Surfing Beach Paralympic Games Start : Musashinonomori Park The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic & 7 1 Cycling Road READY STEADY TOKYO - Cycling (Road) 21 Jul. 2019 Finish : Fuji International Speedway Paralympic Games DAIHATSU YONEX JAPAN OPEN 2019 8 1 Badminton 23-28 Jul. 2019 Musashino Forest Sport Plaza Nippon Badminton Association BADMINTON CHAMPIONSHIPS 9 1 Volleyball Beach Volleyball FIVB Beach Volleyball World Tour 2019 4-star Tokyo 24-28 Jul. 2019 Shiokaze Park Fédération Internationale de Volleyball 10 1 Rowing 2019 World Rowing Junior Championships 7-11 Aug. 2019 Sea Forest Waterway World Rowing Federation Equestrian Park / Sea Forest Cross-Country The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic & 11 1 Equestrian Eventing READY STEADY TOKYO - Equestrian (Eventing) 12-14 Aug. -

CONTENTS ISSUE 74 2 Editorial

COACHING & SPORT SCIENCE REVIEW The Official Tennis Coaching and Sport Science Publication of the International Tennis Federation 26th Year, Issue 74, April 2018 www.itftennis.com/coaching/sportsscience ISSN: 2225-4757 Pg. Title / Author 74 ISSUE CONTENTS 2 Editorial 3 How do LTA mini tennis modifications shape children’s match-play performance? Anna Fitzpatrick , Keith Davids and Joseph Antony Stone (GBR) 6 Tournament planning proposal for a junior player Francisco J. Penalva (ESP) 9 Training matches in women’s tennis (Part 1) Jean-Luc Cotard (FRA) 12 Training matches in women’s tennis (Part 2) Jean-Luc Cotard (FRA) 15 The effect of a variable practice method on tennis groundstroke learning of adult beginners Sahan A., Erman KA., Ertekin E. (TUR) 18 Muscle memory and imagery: Better tennis. An introduction Archie Dan Smith (USA) 20 The inside out stroke in men´s tennis: Strategies and tactics Encarna Martín, José Campos and Miguel Crespo (ESP) 23 Tactical analysis in tennis: From its origins to the present Rafael Martínez (ESP) 25 Winning or losing in wheelchair Grand Slam tournaments Alejandro Sánchez, Antonio Ortega and David Sanz (ESP) 29 Description of the morpho- functional characteristics of junior tennis players Jorge Mauricio Celis (COL) 32 Recommended e-books Editors 33 Recommended web links Editors 34 General guidelines for submitting articles to ITF Coaching & Sport Science Review Editors COACHING & SPORT SCIENCE REVIEW The Official Coaching and Sport Science Publication of the International Tennis Federation EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 74 of the ITF Coaching and Sport Science Review, the first issue of 2018. In this issue, the topics cover a range of aspects in the game including: periodization for juniors, muscle memory and imagery, the inside out forehand, tactical/ notational analysis, adapted equipment, and winning or losing at wheelchair tennis Grand Slam tournaments, among others. -

Executives of the JOC Born May 1954

Yuko ARAKIDA Executive Board Member Executives of the JOC Born May 1954. Chairperson, Athletes Commission. Corporate officer, Japan Volleyball Association. Chairperson, OCA Athletes Committee. Delegation official at Beijing Olympic Games(2008). Gold medalist in volleyball at the Montreal Olympic Games (1976). Organization executive. Tsunekazu TAKEDA President Chiharu IGAYA Executive Board Member, IOC Member Born November 1947. Director, Japan Sports Association. Born May 1931. President, Japan Olympic Academy. Honorary President, Olympians Association of Japan. Vice President, President, Japan Triathlon Union. Vice President, International Japan Equestrian Federation. Member, Coordination Commission Triathlon Union. Silver medalist in alpine skiing (slalom) at the for the XXI and XXII Olympic Winter Games-Vancouver 2010 and Cortina d'Ampezzo Olympic Winter Games (1956). Organization Sochi 2014. Executive Board Member, Olympic Council of Asia executive. (OCA). Executive Council, Association of National Olympic Committees (ANOC). Honorary Vice President, International Equestrian Federation. Corporate executive. Tomiaki FUKUDA Vice President Shun'ichiro OKANO Executive Board Member, IOC Member Born December 1941. Chairman, JOC National Training Center Born August 1931. Supreme Advisor, Japan Football Commission. President, Japan Wrestling Federation. Vice Association. Honorary President, East Asian Football Federation. President, International Federation of Associated Wrestling Chef de Mission, Sapporo Asian Winter Games (1986). Corporate Styles (FILA). Chef de Mission, Olympic Games Beijing (2008). executive. Chef de Mission, Macau East Asian Games (2005). Deputy chef de Mission, Doha Asian Games (2006). Corporate executive. Masato MIZUNO Vice President Masanori OZAKI Executive Board Member Born May 1943. Member, IOC Sport and Environment Born July 1945. Vice Chairman, Administration and Commission. Awarded IOC Olympic Order in 2001. Corporate Coordination Committee. -

2011 ITF Regulations

CONTENTS Please note that where amendments are made in these regulations the text is underlined. Page No. Seniors Committee 1 ITF and Regional Associations 2 National/Seniors Associations 4 SECTION I Regulations for the Organisation of Seniors Circuit Tournaments and the Seniors/Super-Seniors World Individual Championships I. THE COMPETITION 1. Title 14 2. Mission Statement 3. Ownership 15 4. Players Eligible 5. Age Groups 6. Rules to be observed 16 7. Final Ranking II. MANAGEMENT 8. Board of Directors 9. Seniors Committee III. RULES OF THE CIRCUIT 10. Tournament Application and Approval 17 11. Sanction Fees 18 12. Application to host the Seniors/Super-Seniors World Individual Championships 13. ITF Responsibilities 14. Tournament Responsibilities 15. Match Format 19 16. Tournament Grading 17. Method of Ranking 18. Allocation of Points 20 19. ITF Points Tables 22 IV. TOURNAMENT REGULATIONS 20. Variations to Regulations 26 21. Competitors 22. Competitor Obligations 27 23. Insurance 24. One Tournament per Week 25. Number of Entries 26. Qualifying and Consolation draws 28 27. Acceptance of Entries 28. Wild Cards 29 29. Seeding 30. Number of Seeds 30 31. Making a Draw 32. Placing of Seeds 31 33. Byes 32 34. Closing Date for Entries 35. Withdrawals 33 36. Schedule of Play 37. Replacement of Seeds 38. Suspension and Postponement 34 39. Continuous Play 35 40. Duties of the Referee 36 41. Settlement of On Site Disputes 42. ITF Representatives V. ORGANISATIONAL REQUIREMENTS 43. Tournament Fact Sheet and Entry Forms 37 44. Results Sheets 38 45. Entry Fees 46. Prize Money 39 47. Officials 48. Physiotherapist/Athlete Trainer 49. -

Science in Tennis

June 2008 • volume 13 • number 2 medicine and science in tennis • Rolling for recovery • Meet the expert: Dr. Gary Windler • Tennis training • PRO U™ Player Orientation • Best serving strategy Chair www.stms.nl Moroe BEPPU, MD www.stms.nl Congress Organizer Chairman & Professor Department of Orthopedic Surgery St. Marianna University School of Medicine Journal of STMS in co-operation with: ITF • ATP • Sony Ericsson WTA Tour Kawasaki, Japan ISSN: 1567-2352 Medicine and Science in Tennis is a Journal produced by the Society for Tennis Medicine and Science (STMS) in co-operation with the ITF, the ATP, and the Sony Ericsson WTA Tour, and is issued three times a year (February, June, and October). Medicine and Science in Tennis is listed in Altis, Free Medical Journals, MedNets, NewJour, Sponet and SIRC Sports Discus. Th e International Board of the STMS: President: Marc R. Safran, San Francisco, CA, USA E-mail: [email protected] Vice-President: Javier Maquirriain, Buenos Aires, Argentina Message from the President E-mail: [email protected] Secretary/Treasurer: Bill Durney, San Francisco, USA E-mail: [email protected] Membership Offi cer: Todd S. Ellenbecker, Scottsdale, AZ, USA Dear Members, E-mail: [email protected] Past-Presidents: Babette M. Pluim, Ede, the Netherlands Per A.F.H. Renström, Stockholm, Sweden W. Ben Kibler, Lexington, KY, USA Babette Pluim, the founding and current editor of the STMS journal, Additional Members: Peter Jokl, New Haven, CT, USA Bernard Montalvan, Paris, France Associates to the Board: Miguel Crespo, Representative of the ITF has decided to step down after 13 years in offi ce so this will be the Kathy Martin, Representative of the Sony Ericsson WTA Tour Gary Windler, Representative of the ATP last STMS journal she is editing.