Science in Tennis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katharina Krüger Nation: Deutschland Alter: 26 Jahre Schlaghand: Rechts ITF Rangliste: 10 Erfolge Bei Den Austrian Open: 2-Fache Damen Einzelsiegerin

www.s-versicherung.at 113,77 Garantiert staatlich gefördert in Pension mit der s Privat-Pension Auf der Suche nach der richtigen Vorsorge? Mit der s Privat-Pension schaffen Sie sich Ihre finanzielle Unabhängigkeit im Alter und können die volle staatliche Förderung in Anspruch nehmen. 2016 Kommen Sie jetzt in Ihre Erste Bank und Sparkasse. Privat_Pension_A4.indd 1 01.06.16 12:29 Sport als Brücke unserer Gesellschaft Im Sommer steht die Stadtgemeinde Groß-Siegharts wieder ganz im Zeichen des Tennis-Sports und ist Schauplatz des internationalen Rollstuhltennis- turniers. Dazu gratuliere ich herzlich, sage aber zugleich ein aufrichtiges Dankeschön für das Enga- gement und eine durch und durch erfreuliche Ent- wicklung, denn dieses Turnier ist mit Sicherheit eine ganz besondere Veranstaltung für die Teilnehmer, aber auuch für die Region und das Land Nieder- österreich. Auch bei Österreichs größtem Rollstuhltennisturnier in Groß-Siegharts sind wieder bewundernswerte sportliche Leistungen zu erwarten. Von den teilneh- menden Sportlerinnen und Sportlern kann man lernen, was Leistungsbereitschaft, Fairness und Teamgeist bedeuten. Auch hinsichtlich der Fähigkeit, Siege zu feiern und Rückschläge zu verarbeiten, sind die Athletinnen und Athleten wertvolle Vorbilder. Mein aufrichtiger Dank gilt an dieser Stelle allen Personen und Institutionen, die dieses Turnier er- Erwin Pröll möglichen, vor allem aber den Freiwilligen und Eh- renamtlichen, die sich landauf landab für den Sport Landeshauptmann von Niederösterreich engagieren. Als Landeshauptmann wünsche ich allen Beteiligten viel Erfolg, Spannung und natürlich persönliche Freude und Bestleistungen bei den Bewerben. Dr. Erwin Pröll Landeshauptmann von Niederösterreich IMPRESSUM: Herausgeber: Verein Rollstuhltennis Austria Fraslgasse 1, 3812 Groß-Siegharts Layout und Druck: poeppel.at - corporate design e.U. -

La Fédération Française De Tennis a 100 Ans

LA FÉDÉRATION FRANÇAISE DE TENNIS A 100 ANS La connaissez-vous vraiment ? les courts du territoire. Grâce à son plan de relance de 35 millions d’euros et sa plateforme digitale relance.fft.fr, la FFT souhaite soutenir financièrement toutes celles et tous ceux qui participent au succès du tennis en France et dans le 1920 – 2020 monde : clubs affiliés, joueuses et joueurs professionnels, officiels internationaux et organisateurs de tournois. 100 ANS DE PASSION, Désormais centenaire, la FFT s’appuie plus que jamais sur cet héritage – 100 D’ENGAGEMENT ans de passion, d’engagement et d’innovations – pour imaginer l’avenir du tennis ET D’INNOVATIONS et faire figure d’exemple en tant qu’organisation sportive engagée en faveur du développement durable et de la responsabilité sociétale. Avec engagement et vivacité, la Fédération Française de Tennis poursuit l’écriture de la légende du tennis français. Avec près d’un million de licenciés et quatre millions de pratiquants aujourd’hui en France, le tennis est bien plus qu’un sport réservé aux champions et aux records. Au fil des décennies, son histoire est écrite par chacun de ses joueurs et chacune de ses joueuses – amateurs et professionnels –, avec, à leurs côtés, la Fédération Française de Tennis (FFT), qui célèbre en 2020 son centenaire. La passion commune du tennis transcende les générations tant cette discipline ouverte à toutes et à tous permet de découvrir son potentiel et de s’épanouir. Avec ce même élan et depuis maintenant 100 ans, la FFT a contribué à l’évolution de la pratique du tennis en France et dans le monde. -

United States Vs. Czech Republic

United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREVIEW NOTES PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES (U.S. AND CZECH REPUBLIC) U.S. FED CUP TEAM RECORDS U.S. FED CUP INDIVIDUAL RECORDS ALL-TIME U.S. FED CUP TIES RELEASES/TRANSCRIPTS 2017 World Group (8 nations) First Round Semifinals Final February 11-12 April 22-23 November 11-12 Czech Republic at Ostrava, Czech Republic Czech Republic, 3-2 Spain at Tampa Bay, Florida USA at Maui, Hawaii USA, 4-0 Germany Champion Nation Belarus at Minsk, Belarus Belarus, 4-1 Netherlands at Minsk, Belarus Switzerland at Geneva, Switzerland Switzerland, 4-1 France United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 For more information, contact: Amanda Korba, (914) 325-3751, [email protected] PREVIEW NOTES The United States will face the Czech Republic in the 2017 Fed Cup by BNP Paribas World Group Semifinal. The best-of-five match series will take place on an outdoor clay court at Saddlebrook Resort in Tampa Bay. The United States is competing in its first Fed Cup Semifinal since 2010. Captain Rinaldi named 2017 Australian Open semifinalist and world No. 24 CoCo Vandeweghe, No. 36 Lauren Davis, No. 49 Shelby Rogers, and world No. 1 doubles player and 2017 Australian Open women’s doubles champion Bethanie Mattek-Sands to the U.S. team. Vandeweghe, Rogers, and Mattek- Sands were all part of the team that swept Germany, 4-0, earlier this year in Maui. -

Antiguos Oficiales De La Federación Internacional De Tenis 97

Constitution d’ ITF LIMITED 2018 Publicado por la Federación Internacional de Tenis CONSTITUCION DE ITF LTD BANK LANE ROEHAMPTON LONDON SW15 5XZ UK TEL: +44 (0)20 8878 6464 ITF LIMITED 2019 FAX: +44 (0)20 8878 7799 (Versión en vigencia el 27 de septembre de 2019) WEB: WWW.ITFTENNIS.COM QUE OPERA COMO REGISTERED ADDRESS: PO BOX N-272, NASSAU, BAHAMAS LA FEDERATION INTERATIONAL DE TENIS Escritura, Artículos y Estatutos de Constitución de ITF LIMITED Que opera como la Federación Internacional de Tenis 2019 (Versión en vigencia el 27 de septiembre de 2019) ÍNDICE Página número Escritura de Constitución 4 Estatutos de Constitución 1 Interpretación 7 2 Categorías de afiliación 8 3 Solicitudes de afiliación 9 4 Renuncia, suspensión de afiliación, terminación de afiliación y expulsión 12 5 Readmisión de socios 13 6 Suscripciones 14 7 Asociaciones regionales 14 8 Organizaciones reconocidas 16 9 Acciones nominativas 17 10 Transferencia de acciones nominativas 18 11 Derechos de voto exclusivos para los socios de clase B 18 12 Votaciones de los miembros afiliados 19 13 El Consejo 19 14 Asambleas o juntas anuales (ordinarias) 20 15 Asambleas generales (extraordinarias) 21 16 Aviso para asambleas generales 21 17 Aviso de resoluciones 22 18 Conducta de las asambleas generales 22 19 Composición del Consejo de Administración 26 20 El Presidente de la Compañía 27 21 Nominación, elección y condiciones de servicio de los directores 28 22 Facultades y obligaciones de los directores 31 23 Procedimientos del Consejo de Administración 33 24 Oficiales 34 25 Comités -

Wheelchair Doubles Manual

Chapitre 5 – Stratégie #1 : Garder la balle en jeu PRENDRE OU REPRENDRE LE CONTRÔLE DE L'ÉCHANGE Les trois outils utilisés pour prendre ou reprendre la position la plus efficace (placement initial, mouvement, choix de coup) servent aussi à prendre ou reprendre le contrôle de l'échange. Nous allons explorer les nombreuses façons de prendre ou de reprendre le contrôle de l'échange, ainsi que les stratégies, tactiques et situations de jeu connexes. Stratégie #1 - Garder la balle en jeu Dominer constamment les échanges, est tout aussi important que la capacité d'exécuter des coups gagnants d'emblée, qui est assez rare en tennis en fauteuil roulant. Parmi les tactiques reliées à la constance et à la régularité, on trouve notamment : 1.1 Viser de grandes cibles 1.2 Jouer davantage de coups croisés 1.3 Viser haut au dessus du filet 1.4 Exécuter ses meilleurs coups 1.5 Jouer prudemment (tennis «de pourcentage») Le tableau ci-dessous résume ces tactiques : Situations de jeu Fond de Approche ou Contrer ou Service Retour court au filet défendre Tactiques 1.1 Viser de le centre du carré de grandes cibles viser des cibles au ¾ du terrain service largement à à l'intérieur de la ligne de simple l'intérieur des lignes 1.2 Jouer (le filet est plus bas et le terrain est plus long) davantage de coups croisés 1.3 Viser haut au (avant d'atteindre une cible de l'autre côté du terrain, il faut d'abord «passer» le filet) dessus du filet 1.4 Exécuter ses (jouez les coups qui fonctionnent le mieux pour vous : style vs. -

Contemporary Memo

2014 published by itf ltd bank lane roehampton 4 london sw15 5xz uk registered address: po box n-272, nassau, bahamas tel: +44 (0)20 8878 6464 fax: +44 (0)20 8878 7799 web: www.itftennis.Com itf davis Cup regulations 122 NATIONS 488 PLAYERS 1 WORLD CHAMPION SHOW YOUR COLOURS #DAVISCUP BRINGING TENNIS TO THE WORLD SINCE 1900 WWW.DAVISCUP.COM /DAVISCUP @DAVISCUP DAVISCUP CONTENTS I THE COMPETITION 1. Title 1 2. Ownership 1 3. Nations Eligible 1 4. Entries 1 5. Rules and Regulations 2 6. Trophies 3 7. Medical Control 3 II MANAGEMENT 8. Board of Directors 4 9. The Davis Cup Committee 5 10. The Davis Cup Executive Director 5 III PENALTIES AND ARBITRATION 11. Decisions 6 12. Withdrawal of a Nation 6 13. Failure to Send a Team 6 14. Failure to Abide by these Rules and Regulations 6 15. Failure to Carry out Sponsorship Requirements 7 16. Delays and Defaults in Payments and submission of Accounts 7 17. Appeal and Arbitration 7 IV DIVISION OF COMPETITION 18. The World Group 8 19. The Zonal Competitions - Participation 8 20. Americas and Asia/Oceania Zones Group I 9 21. Europe/Africa Zone Group I 10 22. Americas and Asia/Oceania Zones Group II 10 23. Europe/Africa Zone Group II 11 24. Zonal Competitions Group III and Group IV 12 V ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COMPETITION 25. The Draw 12 26. Dates for Rounds 12 27. Choice of Ground 13 28. Minimum Standards for the Organisation of Ties 14 29. General Arrangements for Ties 14 30. Arrangements for Davis Cup Final 15 31. -

Dr Symeon Siomopoulos 2019 Psych

Address: 15 Pafou Str. Papagou, Greece, 15669 Fax & phone No: + 30210 6511058 Greek cell: +306944228374 US cell: (908)265-6772 E-mail: [email protected] Dr Symeon G. Siomopoulos Education v 2010 PhD in Psychology, Department of Psychology, University of Athens, Greece v 2001 Certified Professional tennis coach of the United States Professional Tennis Registry (P.T.R.). v 1999-2001 Masters of Science in Sports Behavior and Performance and Sports Organization, Miami University, Ohio. v 1993-1997 University degree in the department of Physical Education and Athletics Science, University of Athens, Greece, with a specialization in tennis. Presentations/ Ø 2014 Psychological skills training in divers. Part of the certification diploma of Diving coaches papers (certification of Geniki Grammateia) Ø 2008 “Psychological Support of Children and Adolescent Tennis Players”. At the 2nd symposium of coaches and parents held in Volos, Greece Ø 2006 “Psychological Preparation of Divers and Motivational Issues in Their Long Term Development”. At the 1st FINA World Diving Conference held in Athens, Greece Ø 2006 “Coaches and Judges Emotional Situation Before and During Competition”. At the 1st FINA World Diving Conference held in Athens, Greece. Ø 2005 “The Use of Self-Talk in Women’s Varsity Tennis”. Paper published on the Greek Journal of Sport Psychology Ø 2005 “Psychological Support of Children and Adolescent Tennis Players”. At the 1st symposium of coaches and parents held in Tripoli, Greece Ø 2002 “Introduction to Psychological Skills Training in Tennis”. At the National Congress of Tennis Coaches held in Agios Konstantinos, Greece. Ø 2002 “The Use of Self-Talk in Women’s Varsity Tennis”. -

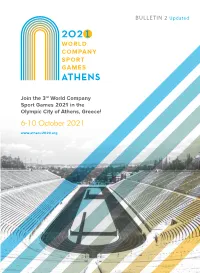

6-10 October 2021

BULLETIN 2 Updated 2021 6-10 October 2021 1 The Games CONTENTS 3rd WORLD COMPANY SPORT GAMES THE GAMES 3 We are proud to host the third edition of the World Company Sport Games that will take place in Athens, Greece from 6 to 10 October 2021! FOREWORD 4 The Company Sport’s heart will be beating in Athens uniting companies and people from 5 continents, demonstrating in the process the beneficial effects of company sport, whilst WFCS 6 carrying a strong message to the whole world: HOCSH 7 “Company sport is not just a sport event: It’s a need!” Following two successful editions of the World Company Sport Games in 2016 and 2018, SPORT DISCIPLINES 8 in Palma de Mallorca and La Baule respectively that welcomed thousands of athletes from across the world, Athens is ready to welcome back companies and competitors that take VENUES 18 part repeatedly in the games and inspire new ones to also participate in this vibrant event. WEBSITE & SOCIAL MEDIA 27 28 SPORT DISCIPLINES IN OLYMPIC VENUES EVENTS 28 The Olympic Athletic Center of Athens – O.A.K.A., the Official Sports Venue of the Olympic Games 2004, will proudly host the World Company Sport Games 2021! Participants will have the GREECE 32 opportunity to compete at the unique facilities of the Olympic Athletic Center of Athens and at other specially selected athletic venues. PARTICIPATION INFORMATION 38 The Organizing Committee of the 3rd World Company Sport Games will host the Opening Ceremony in the “Panathenaic Stadium”, the historical stadium that hosted the first modern HYGIENE PROTOCOL 39 Olympic Games in Athens 1896, providing a unique experience to the participants. -

Alle Gouden Paralympische Medailles Vanaf 1960 263. Bibian

Alle gouden paralympische medailles vanaf 1960 263. Bibian Mentel, Sochi 2014, snowboarden, snowboardcross 262. Esther Vergeer, London 2012, rolstoeltennis, single 261. Esther Vergeer en Marjolein Buis, London 2012, rolstoeltennis, dubbel 260. Kelly van Zon, London 2012, tafeltennis, single 7 259. Mirjam de Koning-Peper, London 2012, zwemmen, 50 meter vrije slag S6 258. Lisette Teunissen, London 2012, zwemmen, 50 meter rugslag S4 257. Michael Schoenmaker, London 2012, zwemmen, 50 meter schoolslag S3 256. Marc Evers, London 2012, zwemmen, 100 meter rugslag S14 255. Udo Hessels, Mischa Rossen en Marcel van de Veen, London 2012, zeilen, Sonar 254. Kathrin Goeken en Kim van Dijk, London 2012, wielrennen, tijdrit B 253. Marlou van Rhijn, London 2012, atletiek, 200 meter T44 252. Esther Vergeer, Beijing 2008, rolstoeltennis, single 251. Korie Homan en Sharon van Walraven, Beijing 2008, rolstoeltennis, dubbel 250. Mirjam de Koning-Peper, Beijing 2008, zwemmen, 50 meter vrije slag S6 249. Mirjam de Koning-Peper, Beijing 2008, zwemmen, 100 meter rugslag S6 248. Pieter Gruijters, Beijing 2008, atletiek, speerwerpen F55/56 247. Esther Vergeer, Athene 2004, rolstoeltennis, single 246. Esther Vergeer en Maaike Smit, Athene 2004, rolstoeltennis, dubbel 245. Robin Ammerlaan, Athene 2004, rolstoeltennis, single 244. Gerben Last en Tonnie Heijnen, Athene 2004, tafeltennis, dubbel 243. Kenny van Weeghel, Athene 2004, atletiek, 400 meter T54 242. Majorie van de Bunt, Salt Lake City 2002, biathlon, 7,5 km vrije techniek staand 241. Esther Vergeer, Sydney 2000, rolstoeltennis, single 240. Esther Vergeer en Maaike Smit, Sydney 2000, rolstoeltennis, dubbel 239. Robin Ammerlaan en Ricky Molier, Sydney 2000, rolstoeltennis, dubbel 238. Syreeta van Amelsvoort, Sydney 2000, zwemmen, 100 meter vlinderslag S8 237. -

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2016 (April 1, 2016 ~ March 31, 2017)

Japan Tennis Association Business Report for FY2016 (April 1, 2016 ~ March 31, 2017) 1. Organizational Management In FY2016, the Japan Tennis Association was run based on the Meeting of the Board of Directors and the monthly Meeting of Executive Directors under the re-elected JTA President, Nobuo Kuroyanagi. However, policies were planned and executed by 25 specialized committees set up under four sectoral departments, namely High Performance, Development, Event Operations, and General/Finance, and by 12 offices established directly under the President, the Senior Executive Director, and the Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Councilors, consisting of 69 representatives of member and cooperative associations and opinion leaders, met twice in the fiscal year and passed resolutions for the FY2016 business results and financial statement as well as the FY2017 business plans and budget. JTA's business scale has expanded since becoming a public interest incorporated foundation (koueki zaidan houjin), thanks to the increasing interest in tennis by Japanese society, implementing projects to strengthen players for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and hosting tournaments. The operating organization required strengthening, which resulted in an amendment in the articles of incorporation by the Board of Councilors. The number of Directors was increased from a maximum of 30 to a maximum of 35 directors, and the number of Executive Directors was increased from 15 to 17. Committee activities expanded, which subsequently increased the workload of the JTA secretariat that supports all committee activities. In particular, during the Japan Tennis Weeks, the tournament operating headquarters and the secretariat showed perfect teamwork in the months of September and October. -

Teams by Year

World TeamTennis - teams by year 1974 LEAGUE CHAMPIONS: DENVER RACQUETS EASTERN DIVISION Atlantic Section Baltimore Banners: Byron Bertram, Don Candy, Bob Carmichael, Jimmy Connors, Ian Crookenden, Joyce Hume, Kathy Kuykendall, Jaidip Mukerjea, Audrey Morse, Betty Stove. Boston Lobsters: Pat Bostrom, Doug Crawford, Kerry Melville, Janet Newberry, Raz Reid, Francis Taylor, Roger Taylor, Ion Tiriac, Andrea Volkos, Stephan Warboys. New York Sets: Fiorella Bonicelli, Carol Graebner, Ceci Martinez, Sandy Mayer, Charlie Owens, Nikki Pilic, Manuel Santana, Gene Scott, Pam Teeguarden, Virginia Wade, Sharon Walsh. Philadelphia Freedoms: Julie Anthony, Brian Fairlie, Tory Fretz, Billie Jean King, Kathy Kuykendall, Buster Mottram, Fred Stolle. COACH: Billie Jean King Central Section Cleveland Nets: Peaches Bartkowicz, Laura DuPont, Clark Graebner, Nancy Gunter, Ray Moore, Cliff Richey, Pat Thomas, Winnie Wooldridge. Detroit Loves: Mary Ann Beattie, Rosie Casals, Phil Dent, Pat Faulkner, Kerry Harris, Butch Seewagen, Lendward Simpson, Allan Stone. Pittsburgh Triangles: Gerald Battrick, Laura DuPont, Isabel Fernandez, Vitas Gerulaitis, Evonne Goolagong, Peggy Michel, Ken Rosewall. COACH: Ken Rosewall Toronto/Buffalo Royals: Mike Estep, Ian Fletcher, Tom Okker, Jan O’Neill, Wendy Overton, Laura Rossouw. WESTERN DIVISION Gulf Plains Section Chicago Aces: Butch Buchholz, Barbara Downs, Sue Eastman, Marcie Louie, Ray Ruffels, Sue Stap, Graham Stilwell, Kim Warwick, Janet Young. Florida Flamingos: Mike Belkin, Maria Esther Bueno, Mark Cox, Cliff Drysdale, Lynn Epstein, Donna Fales, Frank Froehling, Donna Ganz, Bettyann Stuart. Houston EZ Riders: Bill Bowrey, Lesley Bowrey, Cynthia Doerner, Peter Doerner, Helen Gourlay- Cawley, Karen Krantzcke, Bob McKinley, John Newcombe, Dick Stockton. Minnesota Buckskins: Owen Davidson, Ann Hayden Jones, Bob Hewitt, Terry Holladay, Bill Lloyd, Mona Guerrant Wendy Turnbull. -

Wt a Le Gend S

OPEN ERA: MOST SINGLES MATCH WINS MARTINA NAVRATILOVA 1442 CHRIS EVERT 1309 STEFANIE GRAF 902 VIRGINIA WADE 839 WTA LEGENDS: GRAND SLAM CHAMPIONS, FORMER WTA NO.1 RANKED PLAYERS & WTA FINALS CHAMPIONS WTA LEGENDS WTA WTA Legends: Former WTA No.1s, Grand Slam & WTA Finals Champions TRACY AUSTIN USA BIRTHDATE: December 12, 1962 (Palos Verdes Peninsula, CA, USA) • PLAYED: Right-handed (two-handed backhand) CAREER TITLES: 30 singles, 5 doubles • WIN-LOSS: 335-90 singles • PRIZE MONEY: $1,992,380 GRAND SLAM TITLES SINGLES (2): 1981 US Open, 1979 US Open MIXED DOUBLES (1): 1980 Wimbledon (w/John Austin) GRAND SLAM SINGLES HISTORY (Total W-L Record: 61-15) W-L 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 85 84 83 82 81 80 79 78 77 AUSTRALIAN OPEN 3-2 2r – – – – – – – – – – – – QF – – – – ROLAND GARROS 7-3 1r – – – – – – – – – – QF QF – – – – – WIMBLEDON 20-6 – – – – – – – – – – – – QF QF SF SF 4r 3r US OPEN 31-4 – – – – – – – – – – – – QF W SF W QF QF CAREER SNAPSHOT WEEKS AT NO.1: 21 weeks (April 7, 1980) • LAST SINGLES EVENT: July 1994 (Eastbourne) A two-time Grand Slam champion, Austin became the youngest US Open champion in 1979 (16 years, 9 months) and won her second US Open title in 1981. Won the WTA Finals in 1980 and finished as runner-up in 1979, playing Martina Navratilova on both occasions. To this day, holds the record as the youngest WTA player to ever win a singles title by capturing the 1977 Portland title at 14 years, 28 days old. Inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1992, Austin continues to be active in tennis commentating.