Postcolonial Syria and Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

Our Holy Father RAPHAEL Was Born in Syria in 1860 to Pious Orthodox Parents, Michael Hawaweeny and His Second Wife Mariam

In March of 1907 Saint TIKHON returned to Russia and was replaced by From his youth, Saint RAPHAEL's greatest joy was to serve the Church. When Archbishop PLATON. Once again Saint RAPHAEL was considered for episcopal he came to America, he found his people scattered abroad, and he called them to office in Syria, being nominated to succeed Patriarch GREGORY as Metropolitan of unity. Tripoli in 1908. The Holy Synod of Antioch removed Bishop RAPHAEL's name from He never neglected his flock, traveling throughout America, Canada, and the list of candidates, citing various canons which forbid a bishop being transferred Mexico in search of them so that he might care for them. He kept them from from one city to another. straying into strange pastures and spiritual harm. During 20 years of faithful On the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1911, Bishop RAPHAEL was honored for his 15 ministry, he nurtured them and helped them to grow. years of pastoral ministry in America. Archbishop PLATON presented him with a At the time of his death, the Syro-Arab Mission had 30 parishes with more silver-covered icon of Christ and praised him for his work. In his humility, Bishop than 25,000 faithful. The Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of RAPHAEL could not understand why he should be honored merely for doing his duty North America now has more than 240 U.S. and Canadian parishes. (Luke 17:10). He considered himself an "unworthy servant," yet he did perfectly Saint RAPHAEL also was a scholar and the author of several books. -

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO

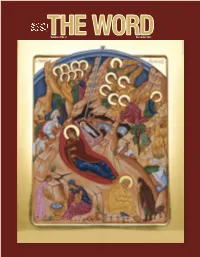

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO. 9 DECEMBER 2017 COVER: ICON OF THE NATIVITY EDITORIAL Handwritten icon by Khourieh Randa Al Khoury Azar Using old traditional technique contents [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL CELEBRATING CHRISTMAS by Bishop JOHN 5 PLEADING FOR THE LIVES OF THE DEFINES US PEOPLE OF THE MIDDLE EAST: THE U.S. VISIT OF HIS BEATITUDE PATRIARCH JOHN X OF ANTIOCH EVERYONE SEEMS TO BE TALKING ABOUT IDENTITY THESE DAYS. IT’S NOT JUST AND ALL THE EAST by Sub-deacon Peter Samore ADOLESCENTS WHO ARE ASKING THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION, “WHO AM I?” RATHER, and Sonia Chala Tower THE QUESTION OF WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN IS RAISED IMPLICITLY BY MANY. WHILE 8 PASTORAL LETTER OF HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH PHILOSOPHERS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE ADDRESSED THIS QUESTION OF HUMAN 9 I WOULD FLY AWAY AND BE AT REST: IDENTITY OVER THE YEARS, GOD ANSWERED IT WHEN THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE AND FUNERAL OF DWELT AMONG US. HE TOOK ON OUR FLESH SO THAT WE MAY PARTICIPATE IN HIS HIS GRACE BISHOP ANTOUN DIVINITY. CHRIST REVEALED TO US WHO GOD IS AND WHO WE ARE TO BE. WE ARE CALLED by Sub-deacon Peter Samore 10 THE GHOST OF PAST CHRISTIANS BECAUSE HE HAS MADE US AS LITTLE CHRISTS BY ACCEPTING US IN BAPTISM CHRISTMAS PRESENTS AND SHARING HIMSELF IN US. JUST AS CHRIST REVEALS THE FATHER, SO WE ARE TO by Fr. Joseph Huneycutt 13 RUMINATION: ARE WE CREATING REVEAL HIM. JUST AS CHRIST IS THE INCARNATION OF GOD, JOINED TO GOD WE SHOW HIM OLD TESTAMENT CHRISTIANS? TO THE WORLD. -

The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - C

Cambridge University Press 0521414113 - The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - c. 1024-c. 1198 Edited by David Luscombe and Jonathan Riley-Smith Index More information INDEX Aachen, 77, 396, 401, 402, 404, 405 Abul-Barakat al-Jarjara, 695, 700 Aaron, bishop of Cologne, 280 Acerra, counts of, 473 ‘Abbadids, kingdom of Seville, 157 Acre ‘Abbas ibn Tamim, 718 11th century, 702, 704, 705 ‘Abbasids 12th century Baghdad, 675, 685, 686, 687, 689, 702 1104 Latin conquest, 647 break-up of empire, 678, 680 1191 siege, 522, 663 and Byzantium, 696 and Ayyubids, 749 caliphate, before First Crusade, 1 fall to crusaders, 708 dynasty, 675, 677 fall to Saladin, 662, 663 response to Fatimid empire, 685–9 Fatimids, 728 abbeys, see monasteries and kingdom of Jerusalem, 654, 662, 664, abbots, 13, 530 667, 668, 669 ‘Abd Allah al-Ziri, king of Granada, 156, 169–70, Pisans, 664 180, 181, 183 trade, 727 ‘Abd al-Majid, 715 13th century, 749 ‘Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar, 155, 158, 160, 163, 165 Adalasia of Sicily, 648 ‘Abd al-Mu’min, 487 Adalbero, bishop of Wurzburg,¨ 57 ‘Abd al-Rahman (Shanjul), 155, 156 Adalbero of Laon, 146, 151 ‘Abd al-Rahman III, 156, 159 Adalbert, archbishop of Mainz, 70, 71, 384–5, ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Ilyas, 682 388, 400, 413, 414 Abelard of Conversano, 109, 110, 111, 115 Adalbert, bishop of Prague, 277, 279, 284, 288, Aberconwy, 599 312 Aberdeen, 590 Adalbert, bishop of Wolin, 283 Abergavenny, 205 Adalbert, king of Italy, 135 Abernethy agreement, 205 Adalgar, chancellor, 77 Aberteifi, 600 Adam of Bremen, 295 Abingdon, 201, 558 Adam of -

Former Ottomans in the Ranks: Pro-Entente Military Recruitment Among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18*

Journal of Global History (2016), 11,pp.88–112 © Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017/S1740022815000364 Former Ottomans in the ranks: pro-Entente military recruitment among Syrians in the Americas, 1916–18* Stacy D. Fahrenthold Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract For half a million ‘Syrian’ Ottoman subjects living outside the empire, the First World War initiated a massive political rift with Istanbul. Beginning in 1916, Syrian and Lebanese emigrants from both North and South America sought to enlist, recruit, and conscript immigrant men into the militaries of the Entente. Employing press items, correspondence, and memoirs written by émigré recruiters during the war, this article reconstructs the transnational networks that facilitated the voluntary enlistment of an estimated 10,000 Syrian emigrants into the armies of the Entente, particularly the United States Army after 1917. As Ottoman nationals, many Syrian recruits used this as a practical means of obtaining American citizen- ship and shedding their legal ties to Istanbul. Émigré recruiters folded their military service into broader goals for ‘Syrian’ and ‘Lebanese’ national liberation under the auspices of American political support. Keywords First World War, Lebanon, mobilization, Syria, transnationalism Is it often said that the First World War was a time of unprecedented military mobilization. Between 1914 and 1918, empires around the world imposed powers of conscription on their -

Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia (S.E.P.S.M.E.A.)

SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page i THE BRITISH AND FRENCH MANDATES IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES / LES MANDATS FRANÇAIS ET ANGLAIS DANS UNE PERSPECTIVE COMPARATIVE SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page ii SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL STUDIES OF THE MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA (S.E.P.S.M.E.A.) (Founding editor: C.A.O. van Nieuwenhuijze) Editor REINHARD SCHULZE Advisory Board Dale Eickelman (Dartmouth College) Roger Owen (Harvard University) Judith Tucker (Georgetown University) Yann Richard (Sorbonne Nouvelle) VOLUME 93 SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page iii THE BRITISH AND FRENCH MANDATES IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES / LES MANDATS FRANÇAIS ET ANGLAIS DANS UNE PERSPECTIVE COMPARATIVE EDITED BY / EDITÉ PAR NADINE MÉOUCHY and/et PETER SLUGLETT WITH/AVEC LA COLLABORATION AMICALE DE GÉRARD KHOURY and/et GEOFFREY SCHAD BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 SEPS-93-meouchy.qxd 10/20/2003 11:03 AM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The British and French mandates in comparative perspectives / edited by Nadine Méouchy and Peter Sluglett ; with Gérard Khoury and Geoffrey Schad = Les mandats français et anglais dans une perspective comparative / édité par Nadine Méouchy et Peter Sluglett ; avec la collaboration amicale de Gérard Khoury et Geoffrey Schad. p. cm. — (Social, economic, and political studies of the Middle East and Asia, ISSN 1385-3376 ; v. 93) Proceedings of a conference held in Aix-en-Provence, June 2001. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 90-04-13313-5 (alk. paper) 1. -

Post-World War I Navigation of Imperialism, Identity, and Nationalism in the 1919-1920 Memoir Entries of Ottoman Army Officer Taha Al-Hāshimī

Post-World War I Navigation of Imperialism, Identity, and Nationalism in the 1919-1920 Memoir Entries of Ottoman Army Officer Taha Al-Hāshimī Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Tomlinson, Jay Sean Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 09:28:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634365 POST-WORLD WAR I NAVIGATION OF IMPERIALISM, IDENTITY, AND NATIONALISM IN THE 1919-1920 MEMOIR ENTRIES OF OTTOMAN ARMY OFFICER TAHA AL-HĀSHIMĪ by Sean Tomlinson ____________________________ Copyright © Sean Tomlinson 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MIDDLE EASTERN AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 Acknowledgements I would like to use this opportunity to acknowledge the support of a lot of amazing people who have encouraged me through my education and time at the University of Arizona. First, I would like to thank Professors Maha Nassar, Benjamin Fortna, Scott Lucas, Gökçe Günel, and Julia Clancy-Smith, for making me feel welcome at the University of Arizona’s School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies, and for encouraging and mentoring me in my studies. Next, I would like to extend my thanks to Professors Riyad al-Homsi, Mohamed Ansary, Muhammad Khudair, and Mahmoud Azaz, for their wonderful instruction in the Arabic language. -

The Significance of Documents in the Codification of Modern and Contemporary Lebanese History Pjaee, 18(7) (2021)

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DOCUMENTS IN THE CODIFICATION OF MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY LEBANESE HISTORY PJAEE, 18(7) (2021) THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DOCUMENTS IN THE CODIFICATION OF MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY LEBANESE HISTORY Instr. Bushra Ibrahim Salman (Ph.D.) Al-Rasheed University College. Instr. Bushra Ibrahim Salman (Ph.D.) , The Significance Of Documents In The Codification Of Modern And Contemporary Lebanese History , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(7). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Documents, Lebanon, modern history, contemporary history. Abstract: Historical documents occupy a pivotal and distinct space on which researchers, historians and who is involved in the field of historical documentation and writing, especially those who specialize in modern and contemporary Lebanese history rely, as they are familiar with relevant and significant documents of specific time periods.Furthermore, documents of all kinds are among the most focal sources of knowledge and the evidence for proving or denying a historical event. In addition, they play a prominent role with the aim of linking the past with the future. Therefore, modern and contemporary Lebanese history is rich in the availability of unpublished and even published documents that presented its historical events in a chronological and in-depth manner. Introduction: It is beyond dispute that historical documents are of great importance, whether political, administrative or legal, which makes them a rich sourceofsolid studies and the basis for scientific research in the field of writing and documenting modern and contemporary Lebanese history in particular. Thus, many countries of the world in the modern era have taken on the provision of centers for the preservation, tabulation, and indexing of documents along with the preparation of paper indexes for the classification of documents, as well as the introduction of technology in the field of documents preservation and archiving so as to facilitate the job of researchers and provide what they need. -

The Istiqlalis in Transjordan, 1920-1926 by Ghazi

A Divided Camp: The Istiqlalis in Transjordan, 1920-1926 by Ghazi Jarrar Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2016 © Copyright by Ghazi Jarrar, 2016 Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................v Chapter One: Introduction.................................................................................................................1 Background.....................................................................................................................................3 Historiography...........................................................................................................................11 Project Parameters and Outline..........................................................................................26 A Note on Sources.....................................................................................................................29 Chapter Two: The Militant Istiqlalis...........................................................................................31 Background..................................................................................................................................32 The Militant Istiqlalis: Part -

The Jewish Discovery of Islam

The Jewish Discovery of Islam The Jewish Discovery of Islam S tudies in H onor of B er nar d Lewis edited by Martin Kramer The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University T el A v iv First published in 1999 in Israel by The Moshe Dayan Cotter for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Tel Aviv 69978, Israel [email protected] www.dayan.org Copyright O 1999 by Tel Aviv University ISBN 965-224-040-0 (hardback) ISBN 965-224-038-9 (paperback) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Publication of this book has been made possible by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Cover illustration: The Great Synagogue (const. 1854-59), Dohány Street, Budapest, Hungary, photograph by the late Gábor Hegyi, 1982. Beth Hatefiitsoth, Tel Aviv, courtesy of the Hegyi family. Cover design: Ruth Beth-Or Production: Elena Lesnick Printed in Israel on acid-free paper by A.R.T. Offset Services Ltd., Tel Aviv Contents Preface vii Introduction, Martin Kramer 1 1. Pedigree Remembered, Reconstructed, Invented: Benjamin Disraeli between East and West, Minna Rozen 49 2. ‘Jew’ and Jesuit at the Origins of Arabism: William Gifford Palgrave, Benjamin Braude 77 3. Arminius Vámbéry: Identities in Conflict, Jacob M. Landau 95 4. Abraham Geiger: A Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reformer on the Origins of Islam, Jacob Lassner 103 5. Ignaz Goldziher on Ernest Renan: From Orientalist Philology to the Study of Islam, Lawrence I. -

118102 JAN. 2009 WORD.Indd

Volume 53 No. 1 January 2009 VOLUME 53 NO. 1 JANUARY 2009 contents COVER THEOPHANY: The Baptism of Christ 3 EDITORIAL by Rt. Rev. John Abdalah 4 CANON 28 OF THE 4TH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL by Metropolitan PHILIP 10 METROPOLITAN PHILIP HOSTS ANTIOCHIAN SEMINARIANS IN ANNUAL EVENT 14 FR. FRED PFEIL INTERVIEWS FR. DAVID ALEXANDER, The Most Reverend US NAVY CHAPLAIN Metropolitan PHILIP, D.H.L., D.D. Primate 17 DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRIES The Right Reverend Bishop ANTOUN 21 ORATORICAL FESTIVAL The Right Reverend Bishop JOSEPH The Right Reverend 23 COMMUNITIES IN ACTION Bishop BASIL The Right Reverend 31 ORTHODOX WORLD Bishop THOMAS The Right Reverend 35 THE PEOPLE SPEAK … Bishop MARK The Right Reverend Bishop ALEXANDER Icons courtesy of Come and See Icons. Founded in Arabic as www.comeandseeicons.com Al Kalimat in 1905 by Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) Founded in English as The WORD in 1957 by Metropolitan ANTONY (Bashir) Editor in Chief The Rt. Rev. John P. Abdalah, D.Min. Assistant Editor Christopher Humphrey, Ph.D. Editorial Board The Very Rev. Joseph J. Allen, Th.D. Anthony Bashir, Ph.D. The Very Rev. Antony Gabriel, Th.M. The Very Rev. Peter Gillquist Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and Ronald Nicola parish. Submissions for “Communities in Action” must be approved by the local Najib E. Saliba, Ph.D. pastor. Both may be edited for purposes of clarity and space. All submissions, in The Very Rev. Paul Schneirla, M.Div. hard copy, on disk or e-mailed, should be double-spaced for editing purposes. -

This Is Not a Revolution: the Sectarian Subject's Alternative In

This is Not a Revolution: The Sectarian Subject’s Alternative in Postwar Lebanon Diana El Richani Under the Supervision of Dr. Meg Stalcup Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Master’s of Arts in Anthropology School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies Faculty of Social Science University of Ottawa ©Diana El Richani, Ottawa, Canada, 2017 Design by William El Khoury Photography by Diana El Richani ii Acknowledgment This work would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of the many people in my life, both in Canada and across the ocean, in Lebanon. Foremost, I thank my supervisor Meg Stalcup for her continuous support, guidance, and encouragement through the countless deadlines and panic-driven days, even weeks. I thank my committee members, Vincent Mirza and Thushara Hewage, for their advice, support, and interest in my work. I also thank my cohort for their support and encouragement throughout the storms. Without the sacrifices and support of my parents, Kamal and Maya, none of this would have been possible. I offer my thanks and love to them, whom I’ve deeply missed over the course of the last few years. And of course, I send love to my brothers, Jamil and Sammy. I thank my friends – William, Ely, Omar, and Zein - for the endless support, the painful laughs, and good company. The heavenly home cooked food definitely did help in those gloomy days. I love these people. I thank Kareem for his constant support and insight. I thank the amazing people that I have had the honor to meet because of this work.