Journal of Precision Teaching Volume 12 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nth Root of a Number Page 1

Lecture Notes The nth Root of a Number page 1 Caution! Currently, square roots are dened differently in different textbooks. In conversations about mathematics, approach the concept with caution and rst make sure that everyone in the conversation uses the same denition of square roots. Denition: Let A be a non-negative number. Then the square root of A (notation: pA) is the non-negative number that, if squared, the result is A. If A is negative, then pA is undened. For example, consider p25. The square-root of 25 is a number, that, when we square, the result is 25. There are two such numbers, 5 and 5. The square root is dened to be the non-negative such number, and so p25 is 5. On the other hand, p 25 is undened, because there is no real number whose square, is negative. Example 1. Evaluate each of the given numerical expressions. a) p49 b) p49 c) p 49 d) p 49 Solution: a) p49 = 7 c) p 49 = unde ned b) p49 = 1 p49 = 1 7 = 7 d) p 49 = 1 p 49 = unde ned Square roots, when stretched over entire expressions, also function as grouping symbols. Example 2. Evaluate each of the following expressions. a) p25 p16 b) p25 16 c) p144 + 25 d) p144 + p25 Solution: a) p25 p16 = 5 4 = 1 c) p144 + 25 = p169 = 13 b) p25 16 = p9 = 3 d) p144 + p25 = 12 + 5 = 17 . Denition: Let A be any real number. Then the third root of A (notation: p3 A) is the number that, if raised to the third power, the result is A. -

Math Symbol Tables

APPENDIX A I Math symbol tables A.I Hebrew letters Type: Print: Type: Print: \aleph ~ \beth :J \daleth l \gimel J All symbols but \aleph need the amssymb package. 346 Appendix A A.2 Greek characters Type: Print: Type: Print: Type: Print: \alpha a \beta f3 \gamma 'Y \digamma F \delta b \epsilon E \varepsilon E \zeta ( \eta 'f/ \theta () \vartheta {) \iota ~ \kappa ,.. \varkappa x \lambda ,\ \mu /-l \nu v \xi ~ \pi 7r \varpi tv \rho p \varrho (} \sigma (J \varsigma <; \tau T \upsilon v \phi ¢ \varphi 'P \chi X \psi 'ljJ \omega w \digamma and \ varkappa require the amssymb package. Type: Print: Type: Print: \Gamma r \varGamma r \Delta L\ \varDelta L.\ \Theta e \varTheta e \Lambda A \varLambda A \Xi ~ \varXi ~ \Pi II \varPi II \Sigma 2: \varSigma E \Upsilon T \varUpsilon Y \Phi <I> \varPhi t[> \Psi III \varPsi 1ft \Omega n \varOmega D All symbols whose name begins with var need the amsmath package. Math symbol tables 347 A.3 Y1EX binary relations Type: Print: Type: Print: \in E \ni \leq < \geq >'" \11 « \gg \prec \succ \preceq \succeq \sim \cong \simeq \approx \equiv \doteq \subset c \supset \subseteq c \supseteq \sqsubseteq c \sqsupseteq \smile \frown \perp 1- \models F \mid I \parallel II \vdash f- \dashv -1 \propto <X \asymp \bowtie [Xl \sqsubset \sqsupset \Join The latter three symbols need the latexsym package. 348 Appendix A A.4 AMS binary relations Type: Print: Type: Print: \leqs1ant :::::; \geqs1ant ): \eqs1ant1ess :< \eqs1antgtr :::> \lesssim < \gtrsim > '" '" < > \lessapprox ~ \gtrapprox \approxeq ~ \lessdot <:: \gtrdot Y \111 «< \ggg »> \lessgtr S \gtr1ess Z < >- \lesseqgtr > \gtreq1ess < > < \gtreqq1ess \lesseqqgtr > < ~ \doteqdot --;- \eqcirc = .2.. -

Using XYZ Homework

Using XYZ Homework Entering Answers When completing assignments in XYZ Homework, it is crucial that you input your answers correctly so that the system can determine their accuracy. There are two ways to enter answers, either by calculator-style math (ASCII math reference on the inside covers), or by using the MathQuill equation editor. Click here for MathQuill MathQuill allows students to enter answers as correctly displayed mathematics. In general, when you click in the answer box following each question, a yellow box with an arrow will appear on the right side of the box. Clicking this arrow button will open a pop-up window with with the MathQuill tools for inputting normal math symbols. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Fraction 6 Parentheses 2 Exponent 7 Pi 3 Square Root 8 Infinity 4 nth Root 9 Does Not Exist 5 Absolute Value 10 Touchscreen Tools Preview Button Next to the answer box, there will generally be a preview button. By clicking this button, the system will display exactly how it interprets the answer you keyed in. Remember, the preview button is not grading your answer, just indicating if the format is correct. Tips Tips will indicate the type of answer the system is expecting. Pay attention to these tips when entering fractions, mixed numbers, and ordered pairs. For additional help: www.xyzhomework.com/students ASCII Math (Calculator Style) Entry Some question types require a mathematical expression or equation in the answer box. Because XYZ Homework follows order of operations, the use of proper grouping symbols is necessary. -

Just-In-Time 22-25 Notes

Just-In-Time 22-25 Notes Sections 22-25 1 JIT 22: Simplify Radical Expressions Definition of nth Roots p • If n is a natural number and yn = x, then n x = y. p • n x is read as \the nth root of x". p { 3 8 = 2 because 23 = 8. p { 4 81 = 3 because 34 = 81. p 2 • When n =p 2 we call it a \square root". However, instead of writing x, we drop the 2 and just write x. So, for example: p { 16 = 4 because 42 = 16. Domain of Radical Expressions • Howp do you find the even root of a negative number? For example, imagine the answer to 4 −16 is the number x. This means x4 = −16. The problem is, if we raise a number to the fourth power, we never get a negative answer: (2)4 = 2 · 2 · 2 · 2 = 16 (−2)4 = (−2)(−2)(−2)(−2) = 16 • Since there is no solution here for x, we say that the fourth root is undefined for negative numbers. • However, the same idea applies to any even root (square roots, fourth roots, sixth roots, etc) p If the expression contains n B where n is even, then B ≥ 0 . Properties of Roots/Radicals p • n xn = x if n is odd. p • n xn = jxj if n is even. p p p • n xy = n x n y (When n is even, x and y need to be nonnegative.) p q n x n x p • y = n y (When n is even, x and y need to be nonnegative.) p p m • n xm = ( n x) (When n is even, x needs to be nonnegative.) mp p p • n x = mn x 1 Examples p p 1. -

Proving the Existence of the Nth Root by Induction

Proving the existence of the nth root by induction. Alvaro Salas∗ Abstract In this paper we prove by induction on n that any positive real number has nth root. Key words and phrases: nth root, supremum, least upper bound axiom. 1 Auxiliary facts We define the set R of real numbers as a numeric ordered field in which the following axiom holds: Least Upper Bound Axiom : If = E R is a non empty set bounded from above, then there ∅ 6 ⊆ exists a least upper bound for E. The least upper bound of E is unique and it is denoted by sup E. If x = sup E, then : A. t x for any t E, that is, x is an upper bound for E. ≤ ∈ B. For any δ > 0 we may find t E such that x δ < t x. ∈ − ≤ Definition 1.1 Let n be a positive integer and a> 0. We say that x is a nth root of a if xn = a. It is easy to show that if a has an nth root, then this root is unique. This follows from the fact that if x and y are positive numbers for which xn = yn, then x = y. The nth root of a is denoted by √n a. Lemma 1.1 Suppose that a> 0 and n is a positive integer. The set n arXiv:0805.3303v1 [math.GM] 21 May 2008 E = t 0 t < a . { ≥ | } is not empty and bounded from above. Proof. E is not empty, because 0 E. On the other hand, it is easy to show by induction on n ∈ that (a + 1)n > a. -

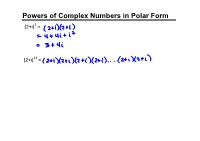

Powers of Complex Numbers in Polar Form (2+I)2 =

Powers of Complex Numbers in Polar Form (2+i)2 = (2+i)12 = Powers of Complex Numbers in Polar Form Let z = r(cosθ +isinθ) z2 = r(cosθ +isinθ)r(cosθ +isinθ) = r2(cos2θ +isin2θ) z3 = r2(cos2θ +isin2θ)r(cosθ +isinθ) = r3(cos3θ +isin3θ) z4 = r3(cos3θ +isin3θ)r(cosθ +isinθ) = r4(cos4θ +isin4θ) The formula for the nth power of a complex number in polar form is known as DeMoivre's Theorem (in honor of the French mathematician Abraham DeMoivre (1667‐1754). DeMoivre's Theorem Let z = r(cosθ+isinθ) be a complex number in polar form. If n is a positive integer, z to the nth power, zn, is zn = [r(cosθ+isinθ)]n = rn[cos(nθ)+isin(nθ)] = rnCiS(nθ) Ex1. Try. Ex2. Try. Roots of a Complex Number in Polar Form Yesterday we saw that [2(cos20o +isin20o)]6 = 64(cos120o + isin120o) Thinking backwards we could note that: A sixth root of 64(cos120o + isin120o) is 2(cos20o +isin20o) It is one of SIX distinct 6th roots of 64cis120o. Nth Root of a Complex Number In general, if a complex number, z, satisfies the equation zn = w, then we can say that z is a complex nth root of w. Also, z is one of n complex nth roots of w. Given the fact that roots are actually powers (remember x1/2 = √x), DeMoivre's Theorem can also be applied to roots... DeMoivre's Theorem for Finding Complex Roots Let w = rcisθ be a complex number in polar form. If w ≠ 0, then w has n distinct complex nth roots given by the formula: (radians) or (degrees) where k = 0, 1, 2, ..., n‐1. -

Complex Numbers and Polar Coordinates Complex Numbers

CHAPTER 8 Complex Numbers and Polar Coordinates Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. SECTION 8.4 Roots of a Complex Number Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Learning Objectives 1 Find both square roots of a complex number. 2 Find all nth roots of a complex number. 3 Graph the nth roots of a complex number. 4 Use roots to solve an equation. 3 Roots of a Complex Number Every real (or complex) number has exactly two square roots, three cube roots, and four fourth roots. In fact, every real (or complex) number has exactly n distinct nth roots, a surprising and attractive fact about numbers. The key to finding these roots is trigonometric form for complex numbers. 4 Roots of a Complex Number Suppose that z and w are complex numbers such that w is an nth root of z. That is, 5 Example 1 Find the four fourth roots of . Solution: According to the formula given in our theorem on roots, the four fourth roots will be 6 Example 1 – Solution cont’d Replacing k with 0, 1, 2, and 3, we have 7 Example 1 – Solution cont’d It is interesting to note the graphical relationship among these four roots, as illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1 8 Example 1 – Solution cont’d Because the modulus for each root is 2, the terminal point of the vector used to represent each root lies on a circle of radius 2. The vector representing the first root makes an angle of /n = 15° with the positive x-axis, then each following root has a vector that is rotated an additional 360°/n = 90° in the counterclockwise direction from the previous root. -

Analysis of the Relationship Between the Nth Root Which Is a Whole Number and the N Consecutive Odd Numbers

http://jct.sciedupress.com Journal of Curriculum and Teaching Vol. 4, No. 2; 2015 Analysis of the Relationship between the nth Root which is a Whole Number and the n Consecutive Odd Numbers Kwenge Erasmus1,*, Mwewa Peter2 & Mulenga H.M3 1Mpika Day Secondary School, P.O. Box 450004, Mpika, Zambia 2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Mukuba University, P.O. Box 20382, Itimpi, Kitwe, Zambia 3Department of Mathematics, Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692, Kitwe, Zambia *Correspondence: Mpika Day Secondary School, P.O. Box 450004, Mpika, Zambia. Tel: 260-976-379-410. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 22, 2015 Accepted: July 12, 2015 Online Published: August 7, 2015 doi:10.5430/jct.v4n2p35 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/jct.v4n2p35 Abstract The study was undertaken to establish the relationship between the roots of the perfect numbers and the n consecutive odd numbers. Odd numbers were arranged in such a way that their sums were either equal to the perfect square number or equal to a cube. The findings on the patterns and relationships of the numbers showed that there was a relationship between the roots of numbers and n consecutive odd numbers. From these relationships a general formula was derived which can be used to determine the number of consecutive odd numbers that can add up to get the given number and this relationship was used to define the other meaning of nth root of a given perfect number from consecutive n odd numbers point of view. If the square root of 4 is 2, then it means that there are 2 consecutive odd numbers that can add up to 4, if the cube root of 27 is 3, then there are 3 consecutive odd number that add up to 27, if the fifth root of 32 is 5, then it means that there are 5 consecutive odd numbers that add up to 32. -

Analytic Solutions to Algebraic Equations

Analytic Solutions to Algebraic Equations Mathematics Tomas Johansson LiTH{MAT{Ex{98{13 Supervisor: Bengt Ove Turesson Examiner: Bengt Ove Turesson LinkÄoping 1998-06-12 CONTENTS 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Quadratic, cubic, and quartic equations 5 2.1 History . 5 2.2 Solving third and fourth degree equations . 6 2.3 Tschirnhaus transformations . 9 3 Solvability of algebraic equations 13 3.1 History of the quintic . 13 3.2 Galois theory . 16 3.3 Solvable groups . 20 3.4 Solvability by radicals . 22 4 Elliptic functions 25 4.1 General theory . 25 4.2 The Weierstrass } function . 29 4.3 Solving the quintic . 32 4.4 Theta functions . 35 4.5 History of elliptic functions . 37 5 Hermite's and Gordan's solutions to the quintic 39 5.1 Hermite's solution to the quintic . 39 5.2 Gordan's solutions to the quintic . 40 6 Kiepert's algorithm for the quintic 43 6.1 An algorithm for solving the quintic . 43 6.2 Commentary about Kiepert's algorithm . 49 7 Conclusion 51 7.1 Conclusion . 51 A Groups 53 B Permutation groups 54 C Rings 54 D Polynomials 55 References 57 2 CONTENTS 3 1 Introduction In this report, we study how one solves general polynomial equations using only the coef- ¯cients of the polynomial. Almost everyone who has taken some course in algebra knows that Galois proved that it is impossible to solve algebraic equations of degree ¯ve or higher, using only radicals. What is not so generally known is that it is possible to solve such equa- tions in another way, namely using techniques from the theory of elliptic functions. -

A Quick Guide to LATEX

A quick guide to LATEX What is LATEX? Text decorations Lists LATEX(usually pronounced \LAY teck," sometimes \LAH Your text can be italics (\textit{italics}), boldface You can produce ordered and unordered lists. teck," and never \LAY tex") is a mathematics typesetting (\textbf{boldface}), or underlined description command output program that is the standard for most professional (\underline{underlined}). \begin{itemize} mathematics writing. It is based on the typesetting program Your math can contain boldface, R (\mathbf{R}), or \item T X created by Donald Knuth of Stanford University (his first Thing 1 • Thing 1 E blackboard bold, R (\mathbb{R}). You may want to used these unordered list \item • Thing 2 version appeared in 1978). Leslie Lamport was responsible for to express the sets of real numbers (R or R), integers (Z or Z), A Thing 2 creating L TEX a more user friendly version of TEX. A team of rational numbers (Q or Q), and natural numbers (N or N). A A L TEX programmers created the current version, L TEX 2". To have text appear in a math expression use \text. \end{itemize} (0,1]=\{x\in\mathbb{R}:x>0\text{ and }x\le 1\} yields Math vs. text vs. functions \begin{enumerate} (0; 1] = fx 2 R : x > 0 and x ≤ 1g. (Without the \text In properly typeset mathematics variables appear in italics command it treats \and" as three variables: \item (e.g., f(x) = x2 + 2x − 3). The exception to this rule is Thing 1 1. Thing 1 (0; 1] = fx 2 R : x > 0andx ≤ 1g.) ordered list predefined functions (e.g., sin(x)). -

Power, Roots, and Radicals Chapter 7.1: Nth Roots and Rational

Chapter 7: Power, Roots, and Radicals Chapter 7.1: Nth Roots and Rational Exponents Evaluating nth Roots: Relating Indices and Powers √ √ Real nth Roots: Let be an integer greater than 1 and let be a real number. If is odd, then has one real nth root: If is even and , then has two real nth roots: If is even and , then has one nth root: If is even and , then has no real nth roots. Example: Find the indicated nth root(s) of . n = 5, a = -32 n = 4, a = 625 n = 3, a = 64 n = 3, a = -27 Rational Exponents: Let ⁄ be an nth root of a, and let m be a positive integer. ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ( √ ) ⁄ ( ⁄ ) ( √ ) Example: Evaluating Expressions with Rational Exponents ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ Example Use a calculator to approximate: √ √ Solving Equations: Example: Solve each equation. ( ) ( ) Example: The rate at which an initial deposit will grow to a balance in years with interest ⁄ compounded n times a year is given by the formula [( ) ]. Find if , , years, and . Example: A basketball has a volume of about 455.6 cubic inches. The formula for the volume of a basketball is . Find the radius of the basketball. Chapter 7.2: Properties of Rational Exponents Properties of Rational Exponents and Radicals Example: Simplify. ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ⁄ Example: Simplify. ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ( ) ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ⁄ Example: Simplify. √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Simplest Form: Checklist for writing radicals in simplest form: Example: Write in simplest form. √ √ Combining Like Radicals: Example: Perform the indicated operation. ⁄ ⁄ ( ) ( ) √ √ ( ⁄ ) ( ⁄ ) √ √ Properties with Variables: Example: Simplify the expression. Assume all variables are positive. √ √ ( ) ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ Example: Write the expression in simplest form. Assume all variables are positive. √ √ Example: Simplify the expression. -

Unicodemath a Nearly Plain-Text Encoding of Mathematics Version 3.1 Murray Sargent III Microsoft Corporation 16-Nov-16

Unicode Nearly Plain Text Encoding of Mathematics UnicodeMath A Nearly Plain-Text Encoding of Mathematics Version 3.1 Murray Sargent III Microsoft Corporation 16-Nov-16 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Encoding Simple Math Expressions ...................................................................... 3 2.1 Fractions .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Subscripts and Superscripts........................................................................... 6 2.3 Use of the Blank (Space) Character ............................................................... 8 3. Encoding Other Math Expressions ........................................................................ 8 3.1 Delimiters ........................................................................................................ 8 3.2 Literal Operators ........................................................................................... 11 3.3 Prescripts and Above/Below Scripts ........................................................... 11 3.4 n-ary Operators ............................................................................................. 12 3.5 Mathematical Functions ............................................................................... 13 3.6 Square Roots and Radicals ........................................................................... 14 3.7 Enclosures ....................................................................................................