Wiko-JB-2008-09.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Un Accident Et L'hôpital

8 Un accident et l’hôpital Objectifs In this chapter you will learn to: ✔ talk about accidents and medical problems ✔ talk about emergency room procedures ✔ ask different types of questions ✔ tell people what to do ✔ compare people and things ✔ talk about a medical emergency in France Jean Geoffroy Le jour de la visite à l’hôpital 246 VVocabulaireocabulaire Mots 1 Un accident appeler police secours glisser tomber se fouler la cheville la cheville La pauvre Anne s’est foulé la cheville. Au service des urgences le service des urgences Qu’est-ce qui t’est arrivé? Je me suis fait mal. J’ai eu une ambulance un accident. T’en fais pas, c’est pas grave. un brancard Les secouristes sont arrivés. Ils ont emmené Anne à l’hôpital en ambulance. 248 deux cent quarante-huit CHAPITRE 8 Le corps le bras se tordre le genou le genou un fauteuil roulant le pied une béquille le doigt de pied la jambe Émilie s’est cassé la jambe. Elle marche avec des béquilles. des points de suture Vous avez mal où? Montrez-moi. J’ai mal au doigt. Ça va mieux. le doigt un pansement Maryse s’est blessée. L’infirmière la soigne. Qu’est-ce qui lui est arrivé? Elle lui fait un pansement. Elle s’est coupé le doigt. C’est une petite blessure. UN ACCIDENT ET L’HÔPITAL deux cent quarante-neuf 249 Vocabulaire Quel est le mot? 1 Qu’est-ce que c’est? Identifiez. 1. C’est une 2. C’est une jambe 3. C’est une salle ambulance ou ou une cheville? d’opération ou le une voiture? service des urgences? 4. -

Sommaire Catalogue National Octobre 2011

SOMMAIRE CATALOGUE NATIONAL OCTOBRE 2011 Page COMPACT DISCS Répertoire National ............................................................ 01 SUPPORTS VINYLES Répertoire National ............................................................. 89 DVD / HDDVD / BLU-RAY DVD Répertoire National .................................................... 96 L'astérisque * indique les Disques, DVD, CD audio, à paraître à partir de la parution de ce bon de commande, sous réserve des autorisations légales et contractuelles. Certains produits existant dans ce listing peuvent être supprimés en cours d'année, quel qu'en soit le motif. Ces articles apparaîtront de ce fait comme "supprimés" sur nos documents de livraison. NATIONAL 1 ABD AL MALIK Salvatore ADAMO (Suite) Château Rouge Master Serie(MASTER SERIE) 26/11/2010 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 20/08/2009 POLYDOR / POLYDOR (557)CD (899)CD #:GACFCH=ZX]\[V: #:GAAHFD=V^[U[^: Dante Zanzibar + La Part De L'Ange(2 FOR 1) 03/11/2008 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 19/07/2010 POLYDOR / POLYDOR (561)CD (928)2CD #:GAAHFD=VW]\XW: #:GAAHFD=W]ZWYY: Isabelle ADJANI Château Rouge Pull marine(L'ORIGINAL) 14/02/2011 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 08/04/1991 MERCURY / MERCURY (561)CD (949)CD #:GACFCH=[WUZ[Z: #:AECCIE=]Y]ZW\: ADMIRAL T Gibraltar Instinct Admiral 12/06/2006 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 19/04/2010 AZ / AZ (899)CD (557)CD #:GACEJI=X\^UW]: #:GAAHFD=W[ZZW^: Le face à face des coeurs Instinct Admiral(ECOPAK) 02/03/2004 BARCLAY / BARCLAY 20/09/2010 AZ / AZ (606)CD (543)CD #:GACEJI=VX\]^Z: #:GAAHFD=W^XXY]: ADAM & EVE Adam & Eve La Seconde Chance Toucher l'horizon -

Digital Booklet Pointdesuture.Pdf

Point de suture LES JOURS DE PEINE PRENDS-MOI DANS TES DRAPS FREDONNENT UN DONNE-MOI LA MAIN JE NE SAIS QUOI NE VIENS PLUS CE SOIR LA RITOURNELLE DIS, JE M’ÉGARE DES INDÉCIS, DES QUOI ? PAR HABITUDE DIS-MOI D’OÙ JE VIENS J’AI PRIS CE CHEMIN NE DIS RIEN, JE PARS D’INCERTITUDE REJOUE-MOI TA MORT Où MES VA SONT DES VIENS JE M’ÉVAPORE JOURS DE SAGESSE DES MOTS SUR NOS RÊVES LA VOIE UNIE ET DROITE DÉPOSER MES DOUTES MAIS L’HOMME DOUTE ET SUR LES BLESSURES ET COURT POINT DE SUTURES DE MULTIPLES DÉTOURS VAGUE MON ÂME VOLE MON AMOUR VA, PRENDS TON CHEMIN REFAIS-MOI L’AMOR L’ATTENTE EST SOURDE CONFUSION DES PAGES MAIS LA VIE ME RETIENT JE SUIS NAUFRAGE LES NUITS SONT CHAUDES MON SANG CHAVIRE ET TANGUE BÂTEAU FANTÔME QUI BRÛLE JE SUIS TEMPÈTE ET VENT OMBRE ET LUMIÈRE SE JOUENT DE L’AMOUR MES VAGUES REVIENNENT MES FLOTS SONT SI LOURDS C’est dans l’air VANITÉ… C’EST LAID C’EST DANS L’AIR TRAHISON… C’EST LAID C’EST DANS L’AIR LÂCHETÉ… C’EST LAID C’EST DANS L’AIR, C’EST NUCLÉAIRE DÉLATION… C’EST LAID ON S’EN FOUT ON EST TOUT LA CRUAUTÉ…C’EST LAID ON FINIRA AU FOND DU TROU LA CALOMNIE… C’EST LAID L’ÂPRETÉ… C’EST LAID ET… MOI JE CHANTE L’INFAMIE… C’EST LAID MOI JE…M’INVENTE UNE VIE. LES CABOSSÉS VOUS DÉRANGENT LA FATUITÉ…C’EST LAID TOUS LES FÊLÉS SONT DES ANGES LA TYRANNIE… C’EST LAID LES OPPRIMÉS VOUS DÉMANGENT LA FÉLONIE… C’EST LAID LES MAL-AIMÉS, QUI LES VENGE ? MAIS LA VIE C’EST ÇA AUSSI. -

Collection "Ma Collection" De Samafar

Collection "ma collection" de samafar Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 113 Tonton Du Bled Maxi 33T 37000784002 2 France 16 Bit Where Are You ? Maxi 45T 888 417-1 France 16 Bit Changing Minds Maxi 45T 888 814-1 France 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance Maxi 45T 190377 1 France 2 Unlimited The Real Thing Maxi 33T 190 667.1 France 2 Unlimited No One Maxi 33T 190 725.1 France 2 Unlimited No Limit Maxi 45T 190 319.1 France 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive Maxi 45T 190 539.1 France 2 Unlimited Faces Maxi 33T BYTE 12024 - 181.295.5Belgique 20 Years After Magical Medley Maxi 45T 560.136 France 49 Ers Die Walkure Maxi 45T 8.917 France 49 Ers Die Walkure Maxi 45T 8.917 France 501's Feat. Desiree Let The Night Take The Blame Maxi 45T 792849 France 99.9 % Check Out Th Groove Maxi 45T DEBTX 3054 Royaume-Uni A Caus Des Garcons A Caus Des Garcons Maxi 45T 248075-0 Allemagne A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie Maxi 45T 2S 052 52814 Z France A-ha Touchy ! Maxi 45T 921 044-0 D Allemagne A-ha The Sun Always Shine On T.v. Maxi 45T 920 410-0 D Allemagne A-ha Take On Me Maxi 45T 920 336-0 D Allemagne A-ha Stay On These Roads LP 925733-1 / WX 166 Allemagne A-ha Stay On These Roads LP 925733-1 Espagne A-ha I've Been Losing You Maxi 45T 920 557-0 D Allemagne A-ha Cry Wolf Maxi 45T 920 610-0 D Allemagne A.ha The Living Daylights Maxi 45T 920 736-0 D Allemagne Aaliyah Try Again (promo Club) Maxi 33T VUSTDJ167 EU Abba Vouley-vous (vinyl Rouge) Maxi 33T 310801 France Abba Vouley-vous (vinyl Bleu) Maxi 33T 310801 France Abba The Day Before You Came Maxi 33T 310954 France -

Quant À Ce Féroce Desproges… » Les Chroniques De La Haine Ordinaire, Une Émission Radiophonique

Diplôme national de master Domaine - sciences humaines et sociales Mention - sciences de l’information et des bibliothèques Spécialité - cultures de l’écrit et de l’image 2014 juin / « Quant à ce féroce Desproges… » Les Chroniques de la haine ordinaire, une émission radiophonique quotidiennement hargneuse ? émoire de master 1 master de émoire M Romane Coutanson Sous la direction d’Evelyne Cohen Professeure d’Histoire et d’Anthropologie culturelles (XXe siècle) Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Sciences de l'Information et des bibliothèques (ENSSIB-Université de Lyon) Remerciements À madame Evelyne Cohen pour sa clairvoyance, Mais aussi à l’équipe de l’INA pour leur aide précieuse Ou à mes parents, grands-parents et sœurs pour leur présence, Une pensée particulière à madame Sandrine Bourrin sans qui Rien n’aurait eu lieu. Outre ces remerciements bien mérités, ma reconnaissance s’adresse aussi Respectivement à Des amis réfléchis, Incluant leurs relectures critiques. Naturellement, celles-ci ont contribué à l’élaboration de ce « petit pan de [mur jaune », comme ils savent si bien le dire. À monsieur Yves Singer, auditeur sachant auditer et témoigner, Ici s’exprime ma gratitude pour tous ceux qui ont participé à cette aventure. Reste à la raconter Et à la dédier, aussi, à tous ceux qui prendront le temps de la lire. COUTANSON Romane | Diplôme national de master Mémoire de recherche | juin 2014 - 3 - Droits d’auteur réservés. Résumé : Les Chroniques de la haine ordinaire est une émission radiophonique diffusée de février à juin 1986. Son chroniqueur, l’humoriste Pierre Desproges, connu pour la provocation lettrée de son humour noir, réagit à l’actualité pour faire la critique vindicative de la société. -

Les Gangs Maori De Wellington: `` Some People Said That Tribes

Les gangs maori de Wellington : “ Some people said that tribes stopped existing in the 1970s ” Grégory Albisson To cite this version: Grégory Albisson. Les gangs maori de Wellington : “ Some people said that tribes stopped existing in the 1970s ”. Sociologie. Université d’Avignon, 2012. Français. NNT : 2012AVIG1112. tel-00872154 HAL Id: tel-00872154 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00872154 Submitted on 11 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ D’AVIGNON ET DES PAYS DE VAUCLUSE École Doctorale 537 : Culture et Patrimoine Laboratoire Identité Culturelle, Texte et Théâtralité (ICTT) EA 4277 Thèse de doctorat d’études anglophones présentée par : Grégory ALBISSON Soutenue le : 7 décembre 2012 « Some people said that tribes stopped existing in the 1970s » : les gangs maori de Wellington Directrice : Madame la professeure Francine TOLRON Jury : Monsieur Ian CONRICH, professeur à l’UNIVERSITÉ DE DERBY, ROYAUME- UNI Madame Martine PIQUET, professeure à l’ UNIVERSITÉ PARIS- DAUPHINE Monsieur Laurent ROESCH, maître de conférences à l’UNIVERSITÉ D’AVIGNON ET DES PAYS DE VAUCLUSE Monsieur Gilles TEULIÉ, professeur à l’ UNIVERSITÉ D’AIX-MARSEILLE Madame Francine TOLRON, professeure à l’ UNIVERSITÉ D’AVIGNON ET DES PAYS DE VAUCLUSE 0 « Some people said that tribes stopped existing in the 1970s » : les gangs maori de Wellington 1 2 Remerciements Je remercie ma directrice de thèse, Madame la professeure Francine TOLRON, de m’avoir gui- dé et encouragé pendant ces quatre années de thèse. -

CD Audio, DVD Musical, Musique Numérique), Les Diff Usions Radiophoniques Et Les Investissements Publicitaires

Cité de la musique Observatoire de la musique Les marchés de la musique enregistrée 2009 André NICOLAS Responsable de l’Observatoire de la musique apportannuel R Cité de la musique - 221 avenue Jean Jaurès - 75019 PARIS Tél : 01 44 84 44 98 / Fax : 01 44 84 46 58 [email protected] - http://observatoire.cite-musique.fr SOMMAIRE Chiffres clés 2009 5 Analyse générale 10 I. Le marché du CD audio A. Les indicateurs du marché (I) 13 1. Tendances (AI) 13 2. Segmentation des ventes par genres musicaux (AI) 16 3. Segmentation des ventes par distributeurs (AI) 17 4. Segmentation des ventes par canaux de distribution (AI) 17 B. Les meilleures ventes par formats 18 1. Analyse du top 100 CD albums volume 18 2. Analyse du top 100 CD singles volume 22 C. Le CD classique 25 1. Tendances (DI) 25 2. Segmentation des ventes par distributeurs (DI) 26 3. Segmentation des ventes par canaux de distribution (DI) 26 4. Analyse du top 100 CD classique volume 27 D. Le CD jazz / blues 30 1. Tendances (EI) 30 2. Segmentation des ventes par distributeurs (EI) 31 3. Segmentation des ventes par canaux de distribution (EI) 31 4. Analyse du top 100 CD jazz / blues volume 32 E. Le CD musiques du monde 35 1. Tendances (FI) 35 2. Segmentation des ventes par sous-genres (FI) 35 3. Segmentation des ventes par distributeurs (FI) 36 4. Segmentation des ventes par canaux de distribution (FI) 36 5. Analyse du top 100 CD musiques du monde volume 37 II. Le marché du DVD musical A. -

Approche Psycho-Ergonomique De L'usage De La

Approche psycho-ergonomique de l’usage de la simulation en e-learning pour l’apprentissage de procédures : le cas du point de suture Leslie Jannin To cite this version: Leslie Jannin. Approche psycho-ergonomique de l’usage de la simulation en e-learning pour l’apprentissage de procédures : le cas du point de suture. Psychologie. Université de Bretagne occi- dentale - Brest, 2020. Français. NNT : 2020BRES0027. tel-03164835 HAL Id: tel-03164835 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03164835 Submitted on 10 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L'UNIVERSITE DE BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE ECOLE DOCTORALE N° 603 Education, Langages, Interaction, Cognition, Clinique Spécialité : Psychologie Par Leslie JANNIN Approche psycho-ergonomique de l’usage de la simulation en e- learning pour l’apprentissage de procédures Le cas du point de suture Thèse présentée et soutenue à Brest, le 17/06/2020 Unité de recherche : Laboratoire des Sciences et Techniques de l'Information, de la Communication et de la Connaissance, CNRS, UMR 6285, -

L'intégrale Farmer

Introduction Enfance, adolescence, errances ylène pousse son premier cri le 12 septembre M1961, à Pierrefonds, une petite ville située à une trentaine de kilomètres de Montréal au Canada. Ses parents, Max et Marguerite Gautier, sont tous les deux exilés français suite à une mutation professionnelle. En effet, son père est ingénieur des Ponts et Chaussées alors que sa mère s’occupe vaillamment de l’éducation des deux aînés : Jean-Loup et Brigitte. Ce n’est un secret pour personne, Mylène a volontai- rement occulté tous les souvenirs des premières années de sa vie. Elle confiera juste aux journalistes que cette enfance n’était pas si désagréable que cela, mais n’en dira jamais plus. Et le mystère de ces années reste encore préservé à ce jour. Mais à la fin des années 1960, Mylène doit dire adieu aux grandes étendues de neige de Pierrefonds, car une fois le barrage de Manicouagan construit (raison profes- sionnelle de la venue de la famille au Canada), la famille Gautier est rappelée en France et s’installe à Ville- d’Avray, dans le sud-ouest de Paris. 5 L’intégrale myLène Farmer Là, c’est la déchirure totale pour la jeune Mylène qui éprouve des difficultés à s’acclimater à son nouvel environnement. Heureusement, la naissance de Michel Gautier, en 1969, lui met un peu de baume au cœur. Mais pour si peu de temps… En France, c’est le début de sa période la plus noire. Mylène est une adolescente introvertie, mal dans sa peau, confrontée à des problèmes de communication avec sa propre famille. -

Une Enquête Picturale Dans Vies Minuscules Et Vie De Joseph Roulin De Pierre Michon

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL SUR FOND DE TABLEAUX: UNE ENQUÊTE PICTURALE DANS VIES MINUSCULES ET VIE DE JOSEPH ROULIN DE PIERRE MICHON MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES LITTÉRAIRES PAR VIRGINIE HARVEY SEPTEMBRE 2008 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.ü1-2üü6). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens d'abord à remercier mon directeur, Jean-François Hamel, pour ses lectures toujours fines, sa rigueur inégalée et la grande confiance qu'il m'a témoignée tout au long de ce mémoire. -

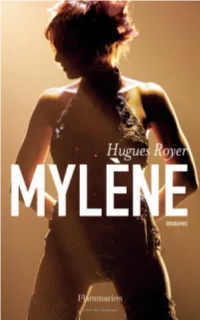

Mylène - Page 1 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02

Extrait de la publication NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 1 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 3 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 MYLE` NE NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 4 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 Du meˆme auteur Mille et Une raisons de rompre, Zulma, 1998. Me´moire d’un re´pondeur, Le Castor Astral, 1999. La Vie sitcom, Verticales, 2001. Comme un seul homme, La Martinie`re, 2004. Ma me`re en plus jeune, Le Cherche-Midi, 2006. Daddy Blue, Le Cherche-Midi, 2007. La Socie´te´ des people, essai, Michalon, 2008. Extrait de la publication NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 5 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 Hugues Royer MYLE` NE Biographie Flammarion NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 6 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 © Flammarion, 2008. ISBN : 978-2-0812-2125-3 NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 7 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 A` Papa... Extrait de la publication NORD COMPO — 03.20.41.40.01 — 152 x 240 — 08-10-08 11:23:46 134778VHY - Flammarion - Mylène - Page 9 — Z34778$$$1 — Rev 18.02 « La vie des autres m’inte´resse beaucoup plus que la mienne. -

Liste Des Articles Par Auteur Alpha Sé- CD Compact Disc Lec- 06-Févr.-17 Tion

Liste des Articles par Auteur Alpha Sé- CD Compact Disc lec- 06-févr.-17 tion NomAuteur RefOuvrage Titre Classement AMB DISQUE AMBIANCE 43É REGIMENT DE LILLE AMB0124 LES PLUS CELEBRES MARCHES MARCHE 43É MILITAIRE A CRÉER AMB0227 A CRÉER ,, BUSS AFRO CELT SOUND SYSTEM AMB0157 CAPTURE 1995 - 2010 AMBIANCE AFR ALAGNA ROBERTO AMB0166 PASION AMBIANCE ALA AMERICAN BALLADS AMB0106 LES PLUS GRANDS MOMENTS COUNTRY AMER COUNTRY ANNE SOFIE VON OTTER & BRAD AMB0154 LOVE SONGS AMB AMBIANCE ANN BAKER JOSEPHINE AMB0050 THE BEST OF COLI BEETHOVEN AMB0120 BEETHOVEN FOR THE BATH CLASSIQUE BEE BEGA LOU AMB0029 A LITTLE BIT OF MAMBO COLI BIGARD AMB0055 LES MEILLEURS MOMENTS HUMOUR CALYPSO ROSE AMB0230 FAR FROM HOME ,, CALY CASH JONNHY AMB0107 COUNTRY JOHNNY CASH RING OF COUNTRY CASH FIRE THE LEGEND OF JOHNNY CASH CHICO & THE GYPSIES AMB0194 FIESTA ,, CHIC COLLECTIF AMB0155 100 TUBES 90'S AMBIANCE COL AMB0144 100% DANCEFLOOR 2009 AMBIANCE COL AMB0081 1996 GRAMMY NOMINEES CHANUTE COLL AMB0084 1997 GRAMMY NOMINEES CHANUTE COLL AMB0083 1998 GRAMMY NOMINEES CHANUTE COLL AMB0156 2011 100 HITS POUR FAIRE LA FETE AMBIANCE COL AMB0071 34 EME FESTIVAL DE LORIENT CELTIQUE COLL AMB0079 35 EME FESTIVAL INTERCELTIQUE DE CELTIQUE COLL LORIENT AMB0098 36 EME FESTIVAL INTERCELTIQUE DE CELTIQUE COLL LORIENT AMB0129 38EME FESTIVAL DE LORIENT CELTIQUE COLL AMB0133 60'S & 70'S VOL 3 AMBIANCE COL AMB0134 60'S & 70'S VOL 5 ,, COLL AMB0200 AFRICAN VOICES ANTHOLOGIY WORLD MUSI CO AMB0135 ANNEE 80 5 CD AMBIANCE COL AMB0099 ANNEE DU ZOUK 2006 ZOUK, COLL AMB0198 ARTE SUMMER OF SOUL