Final Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henkin Clarifies Constitution Extent of Drug Use by Students Is Unknown

• '¥~o~l~--m~'~e~68~,N=-o-.=!l~.~--~--~~----~~~~--------~~1V~_-ak~e--~F-~-~~-~-t~U~DI-.~ve~m-.~-:t-y,-1V~.-~----~~o-n-~~ru-e~m~~-,-N-.C-.--~------~--~------------~--~F~n-.d-a-y-,-F-eh-ru--uy--~l-5-,-l9-85-- Henkin clarifies Constitution Carter lecture is Tuesday Former President Jimmy Carter will By JIM SNYDER congressional body from overstepping , · possesses involves the declaration of The problem of weighing the deliver the annual lrvir.g E. Carlyle Auoclale Editor its bounds. "Because of the nature of war and no president has ever importance of human rights in the lecture Tuesday at 4 p.m. in Wait the Constitution, both Congress and the challenged that authority of Congress. determination of foreign policy is the Chapel. The title of carter's speech is Speaking before a capacity crowd president will continue to pull for more However, according to Henkin, the other major area which Henkin "Human Rights and American Foreign ·Wednesday night in room 102 of the of the b~et," he said. president does have the authority to addressed. He said the president has· Policy." Seales Fine Arts Center, Louis Henkin Henkin believes two theories exist to bring the country to the brink of war nearly full. authority in determining Carter, 60, has been teaching at addr~sed the problems facing a determine the power of. the president, without . ever declaring war himself. whicb nations will be considered as Emory University in Atlanta since he democratic nation iri "formulating "Presidents have asserted ~ry having friendly relations with the left office in 1981. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Atlantic News

Dove 333 Central A GE P U. ATLANTICNEWS.COM VOL 34, NO 34 |AUGUST 22, 2008 | ATLANTIC NEWS | PAGE 1APresor . O. S. J. P AID FOSTER & CO ostal Customer r, POS NH 03820 INSIDE: ted Standard TA ve. TV LISTINGS GE , IN & C. BACK TO SCHOOL Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, AUGUST 22, 2008 Vol. 34 | No. 34 | 24 Pages Monarchs and milkweed Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Diligent monitoring helps conserve butterfly habitats BY LIZ PREMO ly looking for evidence of hart’s face. a measure of success in ticipant in the Minnesota- This is a busy time of ATlaNTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER a familiar seasonal visitor There’s a second one promoting the propagation based Monarch Larva year for monarchs and their ampton resident — the monarch butterfly. finding its way around on of Danaus plexippus, a cause Monitoring Project, Geb- offspring. Linda Gebhart “There’s one!” she another leaf of a nearby which Gebhart wholeheart- hart is joining other indi- “They are very active His on a mission exclaims, pointing to a very milkweed, and further edly supports. In fact, she viduals in locales across because there’s milkweed of royal proportions on a tiny caterpillar less than an investigation reveals a few has even gone so far as to the continent in “collect- in bloom,” Gebhart says, sunny August morning, eighth of an inch long. It’s tiny white eggs stuck to the apply for — and receive — ing data that will help to “so you have the adults just a few steps away from smaller than a grain of rice, undersides of other leaves, the special designation of a explain the distribution drinking the nectar, then her beach cottage. -

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism Kelly Anderson Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/8 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] For Love and For Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The Graduate Center, City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2014 © 2014 KELLY ANDERSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Blanche Wiesen Cook Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Bonnie Anderson Bettina Aptheker Gerald Markowitz Barbara Welter Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson Adviser: Professor Blanche Wiesen Cook This dissertation explores the role of lesbians in the U.S. second wave feminist movement, arguing that the history of women’s liberation is more diverse, more intersectional, -

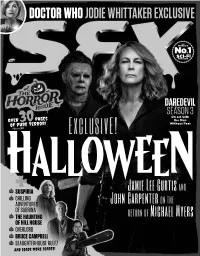

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Page 1 Table of Cases (References Are to Pages.) 1 Tudor City Place

Table of Cases (References are to pages.) 1 Tudor City Place Assocs. v. 2 Tudor City Tenants Corp. ................................................. 1-15 III Lounge, Inc. v. Gaines ........................ 15-13, 15-34, 15-42, 15-43 3M Distrib. Corp. v. Rugby Corp. ................... 2-3, 19-1, 20-8, 30-14 7-Eleven, Inc. v. Stin, LLC ......................................................... 15-99 10 Suf Realty, Inc. v. Fins ............................................................ 11-8 10th & 5th, Inc. v. Arrowsmith .............................................. 16-118 11 W. 42d St., Inc. v. Yardstick, Inc. ......................................... 33-12 12 Broadway Realty, LLC v. Levites ......................................... 10-118 12 Havemeyer Place Co., LLC v. Allan S. Gordon .................... 27-20 12-14 E. 46th St. Corp. v. Kohnstamm-Wolfe, Inc. ................... 33-10 16 Cobalt LLC v. Harrison Career Inst. .........................16-57, 16-58 18th Ave. Pharmacy, Inc. v. Wilmant Realty Corp. ..................... 3-25 20 W. 76th St., LLC v. Div. of Hous. & Cmty. Renewal, In the Matter of ............... 7-18 20/20 Vision Ctr., Inc. v. Hudgens .................................34-33, 34-34 20th Century Lites, Inc. v. Goodman ........................................ 27-35 21 Merchs. Row Corp. v. Merchs. Row, Inc. ......................7-39, 7-60 23 Tracts of Land v. United States ............................................ 13-20 25th Realty Assocs. v. Griggs .................................................... 16-17 27th St. Assocs. v. Lehrer ............................................................ 35-9 28 Mott St. Co. v. Summit Import Corp. ................................. 30-17 29 W. 25th St. Parking Corp. v. Penn Post Parking, Inc. ........................................ 4-8, 7-24, 7-60 30 E. Main St. Serv. Station, Inc. v. H&D All Type Auto Repair, Inc. ......................................... 14-64 30-88 Steinway St., Inc. v. H.C. Bohack Co. .............................. 6-81 31 W. -

Tilda Swinton Over Suspiria “En Dan Hier Een Interviewquote”

AANGEBODEN DOOR UW FILMTHEATER, FDN & NVBF GIRL LUKAS DHONTS FENOMENALE DEBUUT OVER TRANSMEISJE LARA DEBRA GRANIK HET VERSCHIL TUSSEN VERLANGEN EN NODIG HEBBEN MY FOOLISH HEART DE LAATSTE DAGEN VAN CHET BAKER RADICALE RECLAME KUNST VAN DE CAMPAGNE BELLINGCAT WAARHEID IN EEN POST-TRUTH WERELD #414 NOVEMBER 2018 NOVEMBER TILDATILDA SWINTONSWINTON OVEROVER SUSPIRIASUSPIRIA “EN ‘DANSDAN HIER KAN EEN EEN INTERVIEWQUOTE” POLITIEKE EN BETOVERENDE KRACHT ZIJN’ te zien op iDFA en vAnAF 22 november te zien in De FilmtheAters en op DE FILMKRANT #414 NOVEMBER 2018 3 REDACTIONEEL Wat is eigenlijk de kleur van het verleden? Als we naar films kijken dan lijkt het zo logisch dat het verleden zwart- wit is, omdat de eerste films zwart-wit waren. Of goudbruin, zoals het licht van Rembrandt en Caravaggio, laat zonlicht en kaarsen, en de eer- ste elektrische peertjes. Of uitgebleekt, zoals herinneringen kunnen vervagen met de tijd. Soms heeft het verleden juist verzadigde kleu- ren. Tinten rood en groen die al lang niet meer in de mode zijn, maar net zo warm ogen als het textiel waarvan de kleding van de hoofpersona- ges gemaakt is. Wol, katoen. Materialen die kleuren absorberen. Werd de wereld pastel toen de stoffen synthetisch werden? Er is niet één kleur voor het verleden. In het verleden heeft de zon vast ook wel eens zo fel geschenen als op dit moment, terwijl ik in een S-Bahn in Berlijn, hoog langs de Alexanderplatz raas. Hoe zal het heden er in de toekomst als verleden uitzien in films? Voor de onverbeterlijke cinefiel is Alexander- platz voor altijd verbonden aan Rainer Werner Fassbinder. -

Newsletter 12/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 12/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 335 - Dezember 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 12/13 (Nr. 335) Dezember 2013 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, erlebnis jedoch nicht schmälern!” liebe Filmfreunde! Das IMAX-Kino in Bradford ist noch Man gönnt sich ja sonst nichts. Das eines der wenigen in Europa, das tat- war vermutlich der Leitspruch unseres sächlich noch mit horizontal laufendem Film-Bloggers Wolfram, als er sich 70mm-Film arbeitet. Viele andere spontan dazu entschloss, den zweiten IMAX-Kinos wurden inzwischen be- Teil der HUNGER GAMES Saga im fer- reits digitalisiert. Dort wird mit einer 2K nen England anzuschauen. “Das war Doppelprojektion gearbeitet, die eine mein ganz persönliches Kino-Highlight Leinwand mit einem Bildseiten- 2013!” kam er freudestrahlend von sei- verhältnis von etwa 1:1.78 füllt. Das nem Kurztrip zurück. Wolfram hatte Seherlebnis in den digitalen IMAX- sich natürlich nicht irgendein beliebi- Kinos ist daher leider nicht derart ges Kino ausgesucht, um den Film an- spektakulär wie bei analoger zuschauen, sondern gleich das beste. Projektionstechnik. Seit zwei Wochen Die Rede ist vom IMAX-Kino in hat auch Karlsruhe ein solches digita- Bradford, das dort schon seit über 20 les IMAX-Kino. Es befindet sich im Jahren fester Bestandteil des National Filmpalast am ZKM und war Ziel eines Media Museums ist. “Regisseur kleinen Betriebsausflugs der Laser Francis Lawrence setzte in CATCHING Hotline. -

SOUTH END CALDERWOOD PAVILION at the BCA Seasonal Cocktails, Handmade Pasta, Perfectly Cooked Steaks & Fresh Seafood, Expertly Prepared Using the Nest Ingredients

ARRESTING NEW DRAMA A GUIDE FOR THE HOMESICKBY DIRECTED BY KEN COLMAN OCT.6-NOV.4 URBAN DOMINGO SOUTH END CALDERWOOD PAVILION AT THE BCA Seasonal cocktails, handmade pasta, perfectly cooked steaks & fresh seafood, expertly prepared using the nest ingredients. At Davio’s, it’s all about the guest. CONTENTS OCTOBER–NOVEMBER2017 7 THE PROGRAM 10 FROM PLAYWRIGHT KEN URBAN 12 WRESTLING WITH THE PAST PLUS: 04 Backstage by Olivia J. Kiers 10 14 About the Company 34 Patron Services 35 Emergency Exits 38 Guide to Local Theatre 44 Boston Dining Guide 46 Dining Out: Davio’s 12 Nile Hawver theatrebill STAFF Publishing services are provided by Theatrebill, a pub- lication of New Venture Media Group LLC, publisher of President/Publisher: Tim Montgomery Panorama: The Official Guide to Boston, 560 Harrison Ave., Suite 412, Boston, MA 02118, 857-366-8131. Art Director: Scott Roberto Assistant Art Director: Laura Jarvis Editorial Assistant: Olivia J. Kiers WARNING: The photographing or sound recording of any performance or the possession of any device Vice President Publishing: Rita A. Fucillo for such photographing or sound recording inside Vice President Advertising: Jacolyn Ann Firestone this theatre, without the written permission of the Senior Account Executive: Annie Farrell management, is prohibited by law. Violators may be punished by ejection and violations may render the Chief Operating Officer: Tyler J. Montgomery offender liable for money damages. Business Manager: Melissa J. O’Reilly FIRE NOTICE: The exit indicated by a red light and sign nearest to the seat you occupy is the shortest route to the street. In the event of fire or other emer- gencies do not run—WALK TO THAT EXIT. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.