Philos Template PDF Generator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simcity 2000 Manual

™ THE ULTIMATE CITY SIMULATOR USER’S MANUAL Title Pages 3/25/98 12:00 PM Page 1 ª THE ULTIMATE CITY SIMULATOR USER MANUAL by Michael Bremer On the whole I’d rather be in Philadelphia. – W.C. Fields (1879-1946) Credits The Program Designed By: Fred Haslam and Will Wright IBM Programming: Jon Ross, Daniel Browning, James Turner Windows Programming: James Turner, Jon Ross Producer: Don Walters Art Director: Jenny Martin Computer Art: Suzie Greene (Lead Artist), Bonnie Borucki, Kelli Pearson, Eben Sorkin Music: Sue Kasper, Brian Conrad, Justin McCormick Sound Driver: Halestorm, Inc. Sound Effects: Maxis Sample Heds, Halestorm, Inc. Technical Director: Brian Conrad Newspaper Articles: Debra Larson, Chris Weiss Special Technical Assistance: Bruce Joffe (GIS Consultant), Craig Christenson (National Renewable Energy Laboratory), Ray Gatchalian (Oakland Fire Department), Diane L. Zahm (Florida Department of Law Enforcement) The Manual Written By: Michael Bremer Copy Editors: Debra Larson, Tom Bentley Documentation Design: Vera Jaye, Kristine Brogno Documentation Layout: David Caggiano Contributions To Documentation: Fred Haslam, Will Wright, Don Walters, Kathleen Robinson Special Artistic Contributions: John “Bean” Hastings, Richard E. Bartlett, AIA, Margo Lockwood, Larry Wilson, David Caggiano, Tom Bentley, Barbara Pollak, Emily Friedman, Keith Ferrell, James Hewes, Joey Holliday, William Holliday The Package Package Design: Jamie Davison Design, Inc. Package Illustration: David Schleinkofer The Maxis Support Team Lead Testers: Chris Weiss, Alan -

Hacker Public Radio

hpr0001 :: Introduction to HPR hpr0002 :: Customization the Lost Reason hpr0003 :: Lost Haycon Audio Aired on 2007-12-31 and hosted by StankDawg Aired on 2008-01-01 and hosted by deepgeek Aired on 2008-01-02 and hosted by Morgellon StankDawg and Enigma talk about what HPR is and how someone can contribute deepgeek talks about Customization being the lost reason in switching from Morgellon and others traipse around in the woods geocaching at midnight windows to linux Customization docdroppers article hpr0004 :: Firefox Profiles hpr0005 :: Database 101 Part 1 hpr0006 :: Part 15 Broadcasting Aired on 2008-01-03 and hosted by Peter Aired on 2008-01-06 and hosted by StankDawg as part of the Database 101 series. Aired on 2008-01-08 and hosted by dosman Peter explains how to move firefox profiles from machine to machine 1st part of the Database 101 series with Stankdawg dosman and zach from the packetsniffers talk about Part 15 Broadcasting Part 15 broadcasting resources SSTRAN AMT3000 part 15 transmitter hpr0007 :: Orwell Rolled over in his grave hpr0009 :: This old Hack 4 hpr0008 :: Asus EePC Aired on 2008-01-09 and hosted by deepgeek Aired on 2008-01-10 and hosted by fawkesfyre as part of the This Old Hack series. Aired on 2008-01-10 and hosted by Mubix deepgeek reviews a film Part 4 of the series this old hack Mubix and Redanthrax discuss the EEpc hpr0010 :: The Linux Boot Process Part 1 hpr0011 :: dd_rhelp hpr0012 :: Xen Aired on 2008-01-13 and hosted by Dann as part of the The Linux Boot Process series. -

Luigi Documentation Release 2.8.13

Luigi Documentation Release 2.8.13 The Luigi Authors Apr 29, 2020 Contents 1 Background 3 2 Visualiser page 5 3 Dependency graph example 7 4 Philosophy 9 5 Who uses Luigi? 11 6 External links 15 7 Authors 17 8 Table of Contents 19 8.1 Example – Top Artists.......................................... 19 8.2 Building workflows........................................... 23 8.3 Tasks................................................... 28 8.4 Parameters................................................ 33 8.5 Running Luigi.............................................. 36 8.6 Using the Central Scheduler....................................... 38 8.7 Execution Model............................................. 41 8.8 Luigi Patterns............................................... 43 8.9 Configuration............................................... 48 8.10 Configure logging............................................ 60 8.11 Design and limitations.......................................... 61 9 API Reference 63 9.1 luigi package............................................... 63 9.2 Indices and tables............................................ 248 Python Module Index 249 Index 251 i ii Luigi Documentation, Release 2.8.13 Luigi is a Python (2.7, 3.6, 3.7 tested) package that helps you build complex pipelines of batch jobs. It handles dependency resolution, workflow management, visualization, handling failures, command line integration, and much more. Run pip install luigi to install the latest stable version from PyPI. Documentation for the latest release is hosted on readthedocs. Run pip install luigi[toml] to install Luigi with TOML-based configs support. For the bleeding edge code, pip install git+https://github.com/spotify/luigi.git. Bleeding edge documentation is also available. Contents 1 Luigi Documentation, Release 2.8.13 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Background The purpose of Luigi is to address all the plumbing typically associated with long-running batch processes. You want to chain many tasks, automate them, and failures will happen. -

L'expérience De Création De Jeux Vidéo En Amateur Travailler Son

Université de Liège Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Département Médias, Culture et Communication L’expérience de création de jeux vidéo en amateur Travailler son goût pour l’incertitude Thèse présentée par Pierre-Yves Hurel en vue de l’obtention du titre de Docteur en Information et Communication sous la direction de Christine Servais Année académique 2019-2020 À Anne-Lyse, à notre aventure, à nos traversées, à nos horizons. À Charlotte, à tes cris de l’oie, à tes sourires en coin, à tes découvertes. REMERCIEMENTS Écrire une thèse est un acte pétri d’incertitudes, que l’auteur cherche à maîtriser, cadrer et contrôler. J’ai eu le bonheur d’être particulièrement bien accompagné dans cette pratique du doute. Seul face à mon document, j’étais riche de toutes les discussions qui ont jalonné mes années de doctorat. Je souhaite particulièrement remercier mes interlocuteurs pour leur générosité : - Christine Servais, pour sa direction minutieuse, sa franchise, sa bienveillance, ses conseils et son écoute. - Les membres du jury pour avoir accepté de me livrer leur analyse du présent travail. - Tous les membres du Liège Game Lab pour leur intelligence dans leur participation à notre collectif de recherche, pour leur capacité à échanger de manière constructive et pour leur humour sans égal. Merci au Docteure Barnabé (chercheuse internationale et coauteure de cafés-thèse fondateurs), au Docteure Delbouille (brillante sitôt qu’on l’entend), au Docteur Dupont (titulaire d’un double doctorat en lettres modernes et en élégance), au Docteur Dozo (dont le sens du collectif a tant permis), au futur Docteur Krywicki (prolifique en tout domaine), au futur Docteur Houlmont (dont je ne connais qu’un défaut) et au futur Docteur Bashandy (dont le vécu et les travaux incitent à l’humilité). -

Studio Showcase

Contacts: Holly Rockwood Tricia Gugler EA Corporate Communications EA Investor Relations 650-628-7323 650-628-7327 [email protected] [email protected] EA SPOTLIGHTS SLATE OF NEW TITLES AND INITIATIVES AT ANNUAL SUMMER SHOWCASE EVENT REDWOOD CITY, Calif., August 14, 2008 -- Following an award-winning presence at E3 in July, Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: ERTS) today unveiled new games that will entertain the core and reach for more, scheduled to launch this holiday and in 2009. The new games presented on stage at a press conference during EA’s annual Studio Showcase include The Godfather® II, Need for Speed™ Undercover, SCRABBLE on the iPhone™ featuring WiFi play capability, and a brand new property, Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. EA Partners also announced publishing agreements with two of the world’s most creative independent studios, Epic Games and Grasshopper Manufacture. “Today’s event is a key inflection point that shows the industry the breadth and depth of EA’s portfolio,” said Jeff Karp, Senior Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing for Electronic Arts. “We continue to raise the bar with each opportunity to show new titles throughout the summer and fall line up of global industry events. It’s been exciting to see consumer and critical reaction to our expansive slate, and we look forward to receiving feedback with the debut of today’s new titles.” The new titles and relationships unveiled on stage at today’s Studio Showcase press conference include: • Need for Speed Undercover – Need for Speed Undercover takes the franchise back to its roots and re-introduces break-neck cop chases, the world’s hottest cars and spectacular highway battles. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

Module 2 Roleplaying Games

Module 3 Media Perspectives through Computer Games Staffan Björk Module 3 Learning Objectives ■ Describe digital and electronic games using academic game terms ■ Analyze how games are defined by technological affordances and constraints ■ Make use of and combine theoretical concepts of time, space, genre, aesthetics, fiction and gender Focuses for Module 3 ■ Computer Games ■ Affect on gameplay and experience due to the medium used to mediate the game ■ Noticeable things not focused upon ■ Boundaries of games ■ Other uses of games and gameplay ■ Experimental game genres First: schedule change ■ Lecture moved from Monday to Friday ■ Since literature is presented in it Literature ■ Arsenault, Dominic and Audrey Larochelle. From Euclidian Space to Albertian Gaze: Traditions of Visual Representation in Games Beyond the Surface. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. 2014. http://www.digra.org/digital- library/publications/from-euclidean-space-to-albertian-gaze-traditions-of-visual- representation-in-games-beyond-the-surface/ ■ Gazzard, Alison. Unlocking the Gameworld: The Rewards of Space and Time in Videogames. Game Studies, Volume 11 Issue 1 2011. http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/gazzard_alison ■ Linderoth, J. (2012). The Effort of Being in a Fictional World: Upkeyings and Laminated Frames in MMORPGs. Symbolic Interaction, 35(4), 474-492. ■ MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. Game Studies, Volume 14 Issue 2 2014. http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart ■ Nitsche, M. (2008). Combining Interaction and Narrative, chapter 5 in Video Game Spaces : Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds, MIT Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://chalmers.instructure.com/files/738674 ■ Vella, Daniel. Modelling the Semiotic Structure of Game Characters. -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

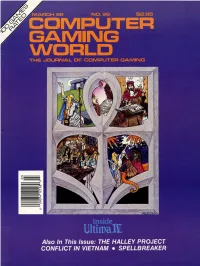

Computer Gaming World Issue 26

Number 26 March 1986 FEATURES Conflict In Viet Nam 14 The View From a Playtester M. Evan Brooks Inside Ultima IV 18 Interview with Lord British The Halley Project 24 Tooling Through the Solar System Gregg Williams Silent Service 28 Designer's Notes Sid Meier Star Trek: The Kobayashi Alternative 36 A Review Scorpia DEPARTMENTS Taking A Peek 6 Screen Photos and Brief Comments Scorpion's Tale 12 Playing Tips on SPELLBREAKER Scorpia Strategically Speaking 22 Game Playing Tips Atari Playfield 30 Koronis Rift and The Eidolon Gregg Williams Amiga Preferences 32 A New Column on the Amiga Roy Wagner Commodore Key 38 Flexidraw, Lode Runner's Rescue, and Little Computer People Roy Wagner The Learning Game 40 Story Tree Bob Proctor Over There 41! A New Column on British Games Leslie B. Bunder Reader Input Device 43 Game Ratings 48 100 Games Rated Accolade is rewarded with an excellent Artworx 20863 Stevens Creek Blvd graphics sequence. Joystick. 150 North Main Street Cupertino, CA 95014 One player. C-64, IBM. ($29.95 Fairport, NY 14450 408-446-5757 & $39.95). Circle Reader Service #4 800-828-6573 FIGHT NIGHT: Arcade style Activision FP II: With Falcon Patrol 2 the boxing game. A choice of six 2350 Bayshore Frontage Road player controls a fighter plane different contenders to battle Mountain View, CA 94043 equipped with the latest mis- for the heavyweight crown. The 800-227-9759 siles to combat the enemy's he- player has the option of using licopter-attack squadrons. Fea- the supplied boxers or creating HACKER: An adventure game tures 3-D graphics, sound ef- his own challenger. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Universidade Federal De Pernambuco Centro De Informática Graduação

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco Centro de Informática Graduação em Ciência da Computação Caio Souza Fonseca GERAÇÃO PROCEDIMENTAL DE CAVERNAS PARA JOGOS DIGITAIS 2D NA UNREAL ENGINE RECIFE, 2016 Caio Souza Fonseca GERAÇÃO PROCEDIMENTAL DE CAVERNAS PARA JOGOS DIGITAIS 2D NA UNREAL ENGINE Trabalho de Graduação apresentado para o curso de Ciência da Computação do Centro de Informática da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Ciência da Computação. Orientador: Geber Lisboa Ramalho ([email protected]) RECIFE, 2016 Caio Souza Fonseca GERAÇÃO PROCEDIMENTAL DE CAVERNAS PARA JOGOS DIGITAIS 2D NA UNREAL ENGINE Trabalho de Graduação apresentado para o curso de Ciência da Computação do Centro de Informática da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Ciência da Computação. Recife, ____ de Julho de 2016 Banca Examinadora _______________________________________________ Prof. Geber Lisboa Ramalho (Orientador) _______________________________________________ Giordano Ribeiro Eulalio Cabral (Avaliador) Agradecimentos Agradeço primeiramente à Deus, por me fornecer todas as oportunidades que eu tive e tenho, oportunidades que me permitiram trabalhar em ótimos locais, ter uma experiência de intercambio, conhecer grandes amigos e finalmente estar onde estou hoje, concluindo este curso. Pela força e coragem que me foram dadas em momentos de fraqueza, perseverança em momentos de desistência e alegria em momentos de tristeza. À minha família em geral, por me dar condições e apoio físico e emocional por toda esta estrada, seja por incentivo, palavras, demonstrações de amor ou orações. Aos meus pais que acreditaram em minhas capacidades e sempre estiveram ao meu lado. A minhas irmãs pela companhia, amizade e momentos de alegria. -

Peabody Company in Center of Oreo Prank Lynn School Sports Back in Play Vaccine Awareness a Priority in Lynn

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2021 Vaccine awareness a priority in Lynn By Allysha Dunnigan and $1 million into the Mas- gage people in conversations ITEM STAFF sachusetts League of Com- about the vaccine. The Lynn City is munity Health Centers. Community Health Center among LYNN — The Baker-Polito The funds provided to com- (LCHC) will receive $25,000 administration has launched munity health centers will of that grant. 20 hard-hit a targeted outreach ini- increase vaccine con dence Dr. Catherine Reyes, a fam- communities tiative to increase vaccine and knowledge throughout ily medicine doctor at Lynn awareness and access to his- the community, implement Community Health Center, putting focus torically underserved com- distribution of culturally said she is relieved and glad on COVID munities. relevant and linguistically that this kind of support is The initiative will invest diverse patient education nally happening, but she ITEM PHOTO | JULIA HOPKINS vaccination resources directly into the materials, and partner with wishes that it happened Dr. Catherine Reyes gives a vaccine to Frank 20 most disproportionately local community-based or- sooner. Williams, of Lynn, at the vaccination clinic at rollout impacted towns and cities ganizations to provide more Lynn Tech Field House. in the state, including Lynn, information and tips to en- VACCINE, A5 Lynn Peabody company in Saugus school center of Oreo prank Town sports Meeting back OKs housing in play on Route 1 By Elyse Carmosino ITEM STAFF By Mike Alongi ITEM SPORTS EDITOR SAUGUS — Town Meeting members voted this week to approve a zoning bylaw amend- LYNN — Lynn public ment requiring all future housing projects school athletic direc- along Route 1 to set aside a percentage of tors, coaches, players space, based on acreage, for commercial use.