THE DEAF-AND-DUMB in the 19Th CENTURY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humberside Police Area

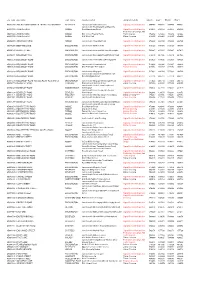

ELECTION OF A POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER for the HUMBERSIDE POLICE AREA - EAST YORKSHIRE VOTING AREA 15 NOVEMBER 2012 The situation of each polling station and the description of voters entitled to vote there, is shown below. POLLING STATIONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO r VOTE r VOTE r VOTE 1 21 Main Street (AA) 2 Kilnwick Village Hall (AB) 3 Bishop Burton Village Hall (AC) Main Street 1 - 116 School Lane 1 - 186 Cold Harbour View 1 - 564 Beswick Kilnwick Bishop Burton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 4 Cherry Burton Village (AD) 5 Dalton Holme Village (AE) 6 Etton Village Hall (AF) Hall 1 - 1154 Hall 1 - 154 37 Main Street 1 - 231 Main Street West End Etton Cherry Burton South Dalton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 7 Leconfield Village Hall (AG) 8 Leven Recreation Hall (AH) 9 Lockington Village Hall (AI) Miles Lane 1 - 1548 East Street 1 - 1993 Chapel Street 1 - 451 Leconfield LEVEN LOCKINGTON EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE 10 Lund Village Hall (AJ) 11 Middleton-On-The- (AK) 12 North Newbald Village Hall (AL) 15 North Road 1 - 261 Wolds Reading Room 1 - 686 Westgate 1 - 870 LUND 7 Front Street NORTH NEWBALD MIDDLETON-ON-THE- WOLDS 13 2 Park Farm Cottages (AM) 14 Tickton Village Hall (AN) 15 Walkington Village Hall (AO) Main Road 1 - 96 Main Street 1 - 1324 21 East End 1 - 955 ROUTH TICKTON WALKINGTON 16 Walkington Village Hall (AO) 17 Bempton Village Hall (BA) 18 Boynton Village Hall (BB) 21 East End 956 - 2 St. -

Restoring the Yorkshire River Derwent

Restoring the Yorkshire River Derwent This factsheet explains the current progress of the River Derwent Restoration Project, and provides an update into the initial findings and the next stages. The River Derwent Restoration Project The Yorkshire River Derwent has been designated as a nationally important Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and as a European Special Area of Conservation (SAC) due to its importance in supporting a wide range of plants and animals. However, changes over time to the land and the way the river has been used has resulted in a deterioration in the quality of habitat and conditions which support this wildlife. Natural England’s last Condition Assessment in 2003 identified that the River Derwent is currently in an unfavourable condition. The Environment Agency is working with Natural England to restore the river to favourable condition. Our work so far • Identification of the main issues To begin planning how to restore the river, we needed In conjunction with the survey, an analysis of existing to understand the river’s current condition and how it information has helped to complete an assessment was behaving. We carried out a survey to understand identifying the main issues influencing the river. the physical processes influencing the river and their These key issues include: subsequent impact on the river ecology. • Excess fine sediment and ‘muddy’ water • Field survey Rainfall washes sediment off of the erodible agricultural soils into drainage ditches and tributaries The survey of the entire length of the River Derwent SSSI and subsequently the river. The increased amount of and SAC between the confluence of the River Rye and room in the river due to historical over-deepening, Barmby on the Marsh was the diversion of water from the Derwent when Sea completed in mid-October Cut operates and the water retaining effect of Barmby 2008. -

72 Swanland Road, Hessle, HU13 0NJ £350,000

TENURE 72 Swanland Road, Freehold. £350,000 Hessle, COUNCIL TAX Band F. HU13 0NJ SERVICES All mains services are connected to the property. None of the services or installations have been tested. VIEWINGS Strictly by appointment with the agent’s Hessle office. 6 Hull Road, Hessle | 01482 644515 | www.dee-atkinson-harrison.co.uk Disclaimer: Dee Atkinson & Harrison for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property, whose Agents they are, give notice that these particulars are produced in good faith, are set out as a general guide only and do not constitute any part of a Contract. No person in the employment of Dee Atkinson & Harrison has any authority to make any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. THE ACCOMMODATION COMPRISES: BEDROOM ONE Built -in double wardrobe and radiator. GROUND FLOOR BEDROOM TWO ENTRANCE HALL Front dormer window and side oriel window. Radiator. A staircase with spindled handrail leads off and there is a built-in shelved cupboard. Radiator. BEDROOM THREE SITTING ROOM BOX ROOM Features a limestone and marble-effect fireplace and front-facing bay window. Two radiators. A sliding BATHROOM glazed door screen opens to the... With a panelled bath and vanity wash-hand basin and electric towel rail. Airing cupboard with hot water tank GARDEN / DINING ROOM (fitted electric immersion heater) and slatted shelving. French windows to the west elevation and double doors with feature coloured glass leaded lights open SEPARATE WC from the sitting room. Two radiators. Low level toilet suite. KITCHEN OUTSIDE A range of fitted cabinets include a low level island and worktops with single drainer sink, built-in electric ATTACHED GARAGE oven and gas hob, plumbing for dishwashing machine Approached by a block-paved private driveway off and automatic washer, concealed gas central heating Pulcroft Road which includes a turning and parking boiler and further built-in cupboard. -

Full Council Meeting 7 April 2021

M A KING A COWEY (Mrs) Town Clerk & RFO Deputy Clerk & Civic Officer PANNETT PARK | WHITBY | YO21 1RE TEL: (01947) 820227 | E MAIL: [email protected] Dear Councillor, 30 March 2021 You are summoned to attend an ordinary meeting of the TOWN COUNCIL OF WHITBY to be conducted on-line, via Zoom and livestreamed on the Town Council‘s Facebook page - https://www.facebook.com/WhitbyTC/ on Wednesday 7 April at 6:00pm, the agenda for which is set out below. To: Councillors Barnett, Coughlan, Dalrymple, Derrick, Michael King Goodberry, Harston, Jackson, Jennison, Lapsley, Nock, Town Clerk Redfern, Smith, Sumner, Wild, Wilson and Winspear NOTICE OF MEETING – Public notice of the meeting is given in accordance with schedule 12, paragraph 10(2) of the Local Government Act 1972. AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE To receive and resolve upon apologies for inability to attend. 2. DECLARATION OF INTERESTS To declare any interests which members have in the following agenda items. 3. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Standing Orders will be suspended for up to 15 minutes to allow for questions or statements about business items on the agenda, submitted by members of the public1 (limited to 3 mins per person). 4. EXTERNAL REPORTS To receive reports on behalf of external bodies if present a. North Yorkshire Police b. County & Borough Councillors 5. ACTIVE TRAVEL FUND – CYCLE PATH PROPOSALS A presentation on the second round of consultation on North Yorkshire County Council’s scheme; seeking views on the draft designs. More information on the second phase of consultation and the draft designs can be found at: https://www.northyorks.gov.uk/social-distancing-measures. -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Barnards Family of South Cave U DDBA Papers of the Barnards Family 1401-1945 of South Cave Historical background: The papers relate to the branch of the family headed by Leuyns Boldero Barnard who began building up a landed estate centred on South Cave in the mid-eighteenth century. His inherited ancestry can be traced back to William and Elizabeth Barnard in the late sixteenth century. Their son, William Barnard, became mayor of Hull and died in 1614. Of his seven sons, two of them also served time as mayor of Hull, including the sixth son, Henry Barnard (d.1661), through whose direct descendants Leuyns Boldero Barnard was eventually destined to succeed. Henry Barnard, married Frances Spurrier and together had a son and a daughter. His daughter, Frances, married William Thompson MP of Humbleton and his son, Edward Barnard, who lived at North Dalton, was recorder of Hull and Beverley from the early 1660s until 1686 when he died. He and his wife Margaret, who was also from the Thompson family, had at least seven children, the eldest of whom, Edward Barnard (d.1714), had five children some of whom died without issue and some had only female heirs. The second son, William Barnard (d.1718) married Mary Perrot, the daughter of a York alderman, but had no children. The third son, Henry Barnard (will at U DDBA/14/3), married Eleanor Lowther, but he also died, in 1769 at the age of 94, without issue. From the death of Henry Barnard in 1769 the family inheritance moved laterally. -

Site Code Site Name Town Name Design Location Designation Notes Start X Start Y End X End Y

site_code site_name town_name design_location designation_notes Start X Start Y End X End Y 45913280 ACC RD SWINEMOOR LA TO EAST RIDING HOSP BEVERLEY Junction with Swinemoor lane Signal Controlled Junction 504405 440731 504405 440731 Junction with Boothferry Road/Rawcliffe 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE Road/Lansdown Road Signal Controlled Junction 473655 424058 473655 424058 Pedestrian Crossings And 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE O/S School Playing Fields Traffic Signals 473602 424223 473602 424223 45900028 AIRMYN ROAD GOOLE O/S West Park Zebra Crossing 473522 424468 473522 424468 45904574 ANDERSEN ROAD GOOLE Junction with Rawcliffe Road Signal Controlled Junction 473422 423780 473422 423780 45908280 BEMPTON LANE BRIDLINGTON Junction with Marton Road Signal Controlled Junction 518127 468400 518127 468400 45905242 BENTLEY LANE WALKINGTON Junction with East End/Mill Lane/Broadgate Signal Controlled Junction 500447 437412 500447 437412 45904601 BESSINGBY HILL BRIDLINGTON Junction with Bessingby Road/Driffield Road Signal Controlled Junction 516519 467045 516519 467045 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Driffield Road/Besingby Hill Signal Controlled Junction 516537 467026 516537 467026 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Thornton Road Signal Controlled Junction 516836 466936 516867 466910 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON O/S Bridlington Fire Station Toucan Crossing 517083 466847 517083 466847 45903639 BESSINGBY ROAD BRIDLINGTON Junction with Kingsgate Signal Controlled Junction 517632 466700 517632 466700 Junction -

3 & 4 Bedroom Homes Ideally Situated in Hessle, East Yorkshire

Linden Homes North, Peninsular House, Hesslewood Office Park, 3 & 4 bedroom homes Hessle, HU13 0PA Telephone 01482 359360 ideally situated in Hessle, East Yorkshire lindenhomes.co.uk/woodlandcroft Welcome to Woodland Croft, traditionally styled family homes in East Yorkshire created by Linden Homes. lindenhomes.co.uk/woodlandcroft Woodland Croft is a wonderful collection of The position of Hessle town means that this is new homes in a highly sought after area of the perfect location for those working in Hull East Yorkshire. Hessle, nestled close to the – just five miles along the A1105 Boothferry banks of the River Humber on the outskirts of Road by car or bus. It is also less than a mile Hull, is the location for Linden Homes’ from the Humber Bridge. Hessle has the desirable, exciting new development. convenience of the railway station with quick access to Leeds. A stunning selection of carefully designed two, three and four-bedroom homes in a Its close proximity to the motorway network range of styles to suit all lifestyle requirements means you are never far away from other and tastes will make up the development off major centres like Beverley, York and Leeds. Swanland Road and Boothferry Road. But don’t just take our word for it – come and Residents will benefit from the best of both see for yourself just what is available. worlds – a fantastic new build home in a bustling location as well as an existing wood- lands walk on the edge of the development. The development will mix the modern with the traditional in terms of house designs and the overall feel of the site, which is expected to attract everyone from first time buyers and young professionals as well as growing families. -

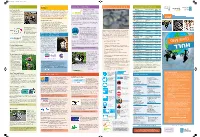

Hull Cycle Map and Guide

Hull Cycles M&G 14/03/2014 11:42 Page 1 Why Cycle? Cycle Across Britain Ride Smart, Lock it, Keep it Cycle Shops in the Hull Area Sustrans is the UK’s leading Bike-fix Mobile Repair Service 07722 N/A www.bike-fix.co.uk 567176 For Your Health Born from Yorkshire hosting the Tour de France Grand Départ, the sustainable transport charity, working z Regular cyclists are as fit as a legacy, Cycle Yorkshire, is a long-term initiative to encourage everyone on practical projects so people choose Repair2ride Mobile Repair Service 07957 N/A person 10 years younger. to cycle and cycle more often. Cycling is a fun, cheap, convenient and to travel in ways that benefit their health www.repair2ride.co.uk 026262 z Physically active people are less healthy way to get about. Try it for yourself and notice the difference. and the environment. EDITION 10th likely to suffer from heart disease Bob’s Bikes 327a Beverley Road 443277 H8 1 2014 Be a part of Cycle Yorkshire to make our region a better place to live www.bobs-bikes.co.uk or a stroke than an inactive and work for this and future generations to come. Saddle up!! The charity is behind many groundbreaking projects including the National Cycle Network, over twelve thousand miles of traffic-free, person. 2 Cliff Pratt Cycles 84 Spring Bank 228293 H9 z Cycling improves your strength, For more information visit www.cycleyorkshire.com quiet lanes and on-road walking and cycling routes around the UK. www.cliffprattcycles.co.uk stamina and aerobic fitness. -

Rigg Farm Caravan Park Stainsacre, Whitby, North Yorkshire

RIGG FARM CARAVAN PARK STAINSACRE, WHITBY, NORTH YORKSHIRE CHARTERED SURVEYORS • AUCTIONEERS • VALUERS • LAND & ESTATE AGENTS • FINE ART & FURNITURE ESTABLISHED 1860 RIGG FARM CARAVAN PARK STAINSACRE WHITBY NORTH YORKSHIRE Robin Hoods Bay 3.5 miles, Whitby 3.5 miles, Scarborough 17 miles, York 45 miles,. (All distances approximates) A WELL PRESENTED CARAVAN PARK IN THE NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK “Rigg Farm Caravan Park is an attractively situated caravan park located in an ideal position for tourists being located between Whitby and Robin Hoods Bay. The property comprises a period 4 bedroom house, attached barn with planning for an annexe, 30 pitch static caravan site, 9 pitch touring caravan site, camping area and associated amenity buildings, situated in around 4.65 acres of mature grounds” CARAVAN PARK: A well established and profitable caravan park set in attractive mature grounds with site licence and developed to provide 30 static pitches and 9 touring pitches. The site benefits from showers and W.C. facilities and offers potential for further development subject to consents. HOUSE: A surprisingly spacious period house with private garden areas. To the ground floor the property comprises: Utility/W.C., Kitchen, Pantry, Office, Conservatory, Dining Room, Living Room. To the first floor are three bedrooms and bathroom. ANNEXE: Attached to the house is an externally completed barn which has planning consent for an annexe and offers potential to develop as a holiday let or incorporate and extend into the main house LAND: In all the property sits within 4.65 acres of mature, well sheltered grounds and may offer potential for further development subject to consents. -

NOTICE of POLL East Riding of Yorkshire Council

East Riding of Yorkshire Council Election of District Councillors BEVERLEY RURAL WARD NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of DISTRICT COUNCILLORS for the WARD of BEVERLEY RURAL will be held on THURSDAY 2 MAY 2019, between the hours of 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM 2. The number of DISTRICT COUNCILLORS to be elected is THREE 3. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidates’ nomination papers are as set out here under :- Candidate Name Address of candidate Description of candidate Names of Proposer and Seconder Names of Assentors Jennifer Ann Stewart Susan Sugars BEAUMONT 19 Fern Close Conservative Party Ian Stewart Audrey Tector Kevin Driffield Candidate John Burnett Elizabeth Holdich E. Yorks Nicholas Dunning Elizabeth Dunning YO25 6UR Paul Staniford Jillian Staniford Jennifer Ann Stewart Susan Sugars GATESHILL 72 New Walkergate Conservative Party Ian Stewart Audrey Tector Bernard Beverley Candidate John Burnett Elizabeth Holdich HU17 9EE Nicholas Dunning Elizabeth Dunning Paul Staniford Jillian Staniford Jennifer Ann Stewart Susan Sugars GREENWOOD Burton Mount Conservative Party Ian Stewart Audrey Tector Pauline Malton Road Candidate John Burnett Elizabeth Holdich Cherry Burton Nicholas Dunning Elizabeth Dunning HU17 7RA Paul Staniford Jillian Staniford Helen Townend E Cameron-Smith GRIMES 17 Eastgate Green Party James Townend Matthew Smith Philip Nigel North Newbald Robert Smith Joyce Elizabeth Smith YO43 4SD Leandro -

SC'ltlcoates Cemetery, Sculcoates Lane-John R. Sculcoates Parochial

840 HULL. SC'ltlcoates Cemetery, Sculcoates lane-John R. Hull, East Yorkshire, and Lincolnshire Deaf Davies, sexton and Dumb Institution, 53 Spring bank Sculcoates Parochial Offices, Bond street-Edw. Jph. A. Wade, J.P., president; Wm. Smith. Wadsley, assistant overseer and vestry clerk hon. sec.; WaIter McOandlish, master S'lttton, Southcoates, If Drypool Gas Co., office, Hull Ladies' Association for the Care of Friend Rt. Mark street-George Oldfield, manager; less Girls, Clarendonhouse,Clarendonstreet David Wood, secretary Mrs. Robinson King, Ferriby, president; Shipping Federation Ltd., Humber Branch Mrs. R. Furley, hon. sec.; Mrs. Shepherd, John Gregson, secretary hon. treas.; and Miss L. Beecham, matron Town Hall, Lowgate Hull Seamen's and General Orphan AS?Jlurn Trinity House, Trinity House lane and Schools, Spring bank-Chas. H. Wilson. Esg., M.P., chairman; W. S. Bailey, J.P., INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIETIES and F. B. Grotrian, Esq., M.P., vice-chair (Literary, Philosphical, and Educational). men; David Wilson, J.P., chairman of house Hull Litera?'y and Philosophical Society and committee; Thomas Reynoldson and Thos. C. Reynoldson, hon. treasurers; Robert M'llSeUm, Royal Institution, Albion street Fras. Bond, M.A.. president; Edward Bolton Middlemiss and R. Gale Middlemiss, hon. secretaries; Thomas Moorby, asst. secretary; and E. J. Wilson, M.A., secretaries; Samuel P. Hudson, curator Miss Lawty, matron; Henry Wilson, school Hull Ch1lrch Institute, Albion st-J. B. Wil master ; Jas. l\Ic.Nidder, J\I.B., hon. surgeon lows, Esq., preSident; W. D. Theaker, hon. Hull Temporary Home for Fallen Females, 25 treasurer; Fredk. F. Ayre, general sec. ; Jas. Nile street-Mrs.