Theft and Finnish Architecture Suzie Thomas University of Helsinki, Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perspectival Inventions of Alvar Aalto

The Perspectival Inventions of Alvar Aalto RANDALL OTT University of Arkansas [Author's note: A considerably expanded and fully illus- rotation is based upon an incorrect assumption about these trated version of this paper will appear in SightBite, The planes' rectangularity. Waterloo Journal of Architecture.] The many perspectival inventions of Aalto reward careful study. Through them his buildings become illusionistic Aalto's architectural compositions never fail to engage our spaces, full of mock shapes and depths that alter unexpect- vision while we approach. No matter how sculptural the edly as we experience them. His distortions create spatial forms of his buildings might seem at first glance, they tensions energized only by a moving observer at the site, thus inevitably surpass themselves in dynamism and visual trans- entwining the viewer's motion and the architecture. These formation when we begin to move about them. Aalto's tensions dramatize our approach, contrasting first impres- success in manipulating complex, dynamic forms no doubt sions with subsequent experiences. Most importantly, they rests on many interrelated aspects of his work. Still, we create a virtual site which itself comes into tension with the should single out for special attention the way he was able to actual site. let his shapes unfold and gesture directly toward us as we walk the site, thus becoming expressive in the most interac- PRECURSORS tive and literal of ways.' The exterior facade of Aalto's Finlandia Hall in Helsinki Aalto, of course, was not the first to build illusory perspec- displays this highly interactive quality. As we move toward tives. -

International Evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery

International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Publications of the Ministry on Education and Culture, Finland 2011:18 International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Publications of the Ministry on Education and Culture, Finland 2011:18 Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö • Kulttuuri-, liikunta- ja nuorisopolitiikan osasto • 2011 Ministry of Education and Culture• Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy • 2011 Ministry of Education and Culture Department for Cultural, Sport and Youth Policy Meritullinkatu 10, Helsinki P.O. Box 29, FIN-00023 Government Finland www.minedu.fi/minedu/publications/index.html Layout: Timo Jaakola ISBN 978-952-263--045-2 (PDF) ISSN-L 1799-0327 ISSN 1799-0335 (Online) Reports of the Ministry of Education and Culture 2011:18 Kuvailulehti Julkaisija Julkaisun päivämäärä Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö 15.4.2011 Tekijät (toimielimestä: toimielimen nimi, puheenjohtaja, sihteeri) Julkaisun laji Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön Kansainvälinen arviointipaneeli: projektipäällikkö Sune Nordgren työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä (pj.) Dr. Prof. Günther Schauerte, johtaja Lene Floris, ja Toimeksiantaja Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö oikeustieteen tohtori Timo Viherkenttä. Sihteeri: erikoissuunnittelija Teijamari Jyrkkiö Toimielimen asettamispvm Dnro 23.6.2010 66/040/2010 Julkaisun nimi (myös ruotsinkielinen) International evaluation of the Finnish National Gallery Julkaisun osat Muistio ja liitteet Tiivistelmä Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö päätti arvioida Valtion taidemuseon toiminnan vuonna 2010. Valtion taidemuseo on ollut valtion virasto vuodesta 1990 lähtien ja sen muodostavat Ateneumin taidemuseo, Nykytaiteen museo Kiasma, Sinebrychoffin taidemuseo ja Kuvataiteen keskusarkisto. Tulosohjattavan laitoksen tukitoimintoja hoitavat konservointilaitos, koko maan taidemuseoalan kehittämisyksikkö sekä hallinto- ja palveluyksikkö. Organisaatiorakenne on pysynyt suurinpiirtein samanlaisena sen koko olemassaolon ajan. Taidemuseon vuosittainen toimintamääräraha valtion budjetissa on n. 19 miljoonaa euroa ja henkilötyövuosia on n. -

Nordic Music Today

18 17 – 23 OCTOBER 2013 WHERE TO GO HELSINKI TIMES COMPILED BY ANNA-MAIJA LAPPI Until Sun 10 November Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg A blend of fantasy and nightmare created by the Swedish contempo- TIINA MIELONEN rary artist duo. Kunsthalle Helsinki Nervanderinkatu 3 Open: Nordic Music Today Tue, Thu, Fri 11:00-18:00 Nordic Music Days, one of the longest continuously running music festivals Wed 11:00-20:00 in the world, is celebrating its 125th birthday this year with a broad pro- Sat, Sun 11:00-17:00 Tickets €0/9/12 gramme of contemporary Nordic music. First held in 1888, the festival aims www.taidehalli.fi to promote the work of contemporary Nordic composers and offer the audi- ences a chance to experience new, vibrant music from the Nordic countries. Until Sun 17 November The theme this year is ‘Parallel Societies’. The theme will be highlight- Timo Heino Installations and collages by one of ed throughout the festival programme that falls into three different cat- the most uncompromising Finnish egories: orchestral and choral concerts, chamber-music concerts and club contemporary artists. evenings featuring electronic and electro-acoustic music. The main con- Helsinki Art Museum Tennis Palace cert venues will be the various halls of the Helsinki Music Centre, the Sibel- Salomonkatu 15 ius Academy Concert Hall, Temppeliaukio Church and the Korjaamo Culture Open: Tue-Sun 11:00-19:00 Factory. Tickets €0/8/10 The festival programme, including performances from choral music to electronic improvisation, has been compiled by a trio of artistic directors: Until Sun 15 December conductor Nils Schweckendiek, guitarist Petri Kumela and composer Sami Surreal Illusionism - Photographic Klemola. -

Loan Terms of Finnish National Gallery (Outgoing Loans)

LOAN TERMS OF FINNISH NATIONAL GALLERY (OUTGOING LOANS) Borrowing works from the collections of the Finnish National Gallery (“FNG”) – Ateneum Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma and Sinebrychoff Art Museum. General terms These terms concern short-term or temporary loans. FNG lends only to museums and exhibition organizers with professional museum staff or a similar level of expertise, as well as appropriately secure and climate-controlled facilities. Loan requests must specify the works to be lent and the loan period, as well as provide an account of the environmental conditions, security and surveillance arrangements in the exhibition galleries. Loan requests must be made in writing to the director of the museum in question – Ateneum Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma or Sinebrychoff Art Museum – at least eight months prior to the loan period for international loans. Each loan request is assessed separately. When deciding on a loan, the things considered include the condition of the work, display conditions particularly in the case of sensitive works, the status of the work in the FNG collections, and other relevant matters such as possible reservations for other exhibitions. Any deviation from these loan terms must be agreed in writing. There is always a loan agreement signed also for media art, whether original works or copies. Insurance Borrowed works of art must be insured against all risks for values determined by FNG. The insurance must run nail to nail, from the moment FNG gives the works over to the Borrower or their representative, up until the moment the works are returned to FNG. -

HENKILÖSTÖEDUT KOULUTUS 2 Monipuolisia& Etuja Ja Koulutusmahdollisuuksia 3 Ostoedut 2018 4 Etuja Ja Bonusta

HENKILÖKUNNAN LEHTI 1/2018 HENKILÖSTÖEDUT KOULUTUS 2 Monipuolisia& etuja ja koulutusmahdollisuuksia 3 Ostoedut 2018 4 Etuja ja bonusta 2018 6 Työ- ja ikämerkkipäivät 7 Työterveyshuolto 8 Sairauskassa ja sopimuspaikat 11 Urapolut 16 Työsuhde- ja loma-asunnot ym. MONIPUOLISIA HOK-ELANTO/HENKILÖKUNNAN OSTOEDUT ETUJA & KOULUTUSMAHDOLLISUUKSIA HOK-Elanto tarjoaa työntekijöilleen monenlaisia henkilös- Vakituisen henkilökuntamme vapaa-ajan tapaturmava- töetuja, sekä konkreettisia ja tuntuvia taloudellisia hyötyjä kuutus ilman korvauskattoa sisältää mm. sairaanhoidon että henkiseen pääomaan ja hyvinvointiin liittyviä etuja. kustannukset, päivärahakorvauksen ja tapaturmaeläk- Osaa eduista voivat hyödyntää myös samassa taloudessa keen. Vakuutus on voimassa kaikkialla maailmassa. asuvat perheenjäsenet. Tällaisia ovat mm. henkilökun- Tämä esite on tietopaketti kaikista HOK-Elannon tarjoa- ta-alennukset HOK-Elannon ja S-ryhmän toimipaikoista, mista henkilöstöeduista ja työhyvinvointiin liittyvistä pal- Vierumäen loma-asuntojen käyttömahdollisuus sekä vuo- veluista. Myös eri toimialojen ja ketjujen urapolut ja niitä sittainen Linnanmäkipäivä. tukevat valmennusohjelmat löydät tästä esitteestä. Tämän vuoden alusta alkaen henkilökuntaetua saa myös Tutustu monipuoliseen tarjontaan ja hyödynnä työnan- Stockmann Herkuista Helsingin keskustassa, Tapiolassa, tajan tarjoamat edut ja kehittymismahdollisuudet! Itiksessä ja Jumbossa. Henkilöstöalennuksen saamiseksi tulee ostokset maksaa henkilökunnan S-Etukortti Visalla, mikä antaa alennuksen Antero Levänen lisäksi -

PROGRAMME Contents

Third European IRPA Congress NSFS Radiation protection – science, safety and security 14 – 18 June 2010 Helsinki, Finland www.irpa2010europe.com PROGRAMME Contents Welcome to European IRPA 2010 . 3 Organisation and committees . 4 Contributing organisations . 5 General information . 6 Finlandia Hall . .8 Programme outline . 1. 0 Monday, 14 June . .12 Tuesday, 15 June . .1 . 4 –27) and Eero Venhola (p. 28), Finnish Tourist Board’s Image Bank (p. 12 top), TVO (p. 12 below), Hotel Hilton Kalastajatorppa (p. 25 top and p. 41 right) and p. 25 top (p. Hilton Kalastajatorppa Hotel TVO 12 below), (p. 12 top), Image Bank (p. Board’s Tourist 28), Finnish (p. Venhola –27) and Eero Wednesday, 16 June . 16 Thursday, 17 June . 20 Friday, 18 June . 26 5), Katri Pyynönen (p. 8 and backdrops on pp. 12 on pp. 8 and backdrops 5), Katri Pyynönen (p. – Poster sessions and presentations . 2. 8 Social programme . 4. 0 Technical exhibition . 42 Graphic design and layout: Nina Sulonen STUK – Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority Photos: City of Helsinki Picture Bank / Matti Tirri (cover and p. 19 top), Comma Image Oy (p.13 top), p. 15 Paul Williams (p. 40 left), Mika Lappalainen (p. 40 right), Pertti Nisonen (p. 41 left), Finlandia Hall Image Bank / Matti Tirri (pp. 4 (pp. Tirri Hall Image Bank / Matti 41 left), Finlandia Nisonen Pertti 40 left), 40 right), (p. Mika (p. Lappalainen (p. Williams 15 Paul p. top), Image Oy Comma (p.13 19 top), and p. (cover Tirri CityPhotos: of Helsinki Bank / Matti Picture 2 Welcome to European IRPA 2010 Dear colleagues from all over Europe and beyond The Nordic Society for Radiation Protection (NSFS) has the honour to host the regional European IRPA Congress in Helsinki on 14 – 18 June 2010. -

Nimistöntutkimusta, Komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -Salapoliisiromaaneissa

Nimistöntutkimusta, komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -salapoliisiromaaneissa Milla Juhonen Pro gradu -tutkielma Suomen kieli Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto Toukokuu 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Suomen kielen ja suomalais-ugrilaisten kielten ja kulttuurien mais- teriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Suomen kieli Tekijä – Författare – Author Juhonen, Milla Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Nimistöntutkimusta, komisario Palmu! Paikannimistö Komisario Palmu -salapoliisiromaaneissa Työn laji – Arbetets art – Le- Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages vel year Pro gradu -tutkielma Toukokuu 2020 65 + 3 liitesivua Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielman aiheena on Komisario Palmu -romaanien paikannimistö. Ensisijaisena tavoitteena on analysoida paikannimien roolia fiktiivisen Helsinki-kuvan rakentamisessa. Lisäksi pyritään muodostamaan kokonaisvaltainen käsitys siitä, millaisia paikannimiä romaaneissa esiintyy. Tutkimuksen aineistona on Kuka murhasi rouva Skrofin? (1939) ja Komisario Palmun erehdys (1940) -romaanien paikannimet. Tutkimusaineistossa on yhteensä 58 paikannimeä. Näistä 39 nimeä viittaa Helsingissä sijaitseviin paikkoihin. 12 nimistä on ulkomailla sijaitsevien paikkojen nimiä ja seitsemän taas viittaa muualla Suomessa sijaitseviin paikkoihin. Nimistä 52 on autenttisia paikannimiä ja kuusi fiktiivisiä. Suurin osa nimistä viittaa alueisiin (25 nimeä), kulkuväyliin ja rakennelmiin -

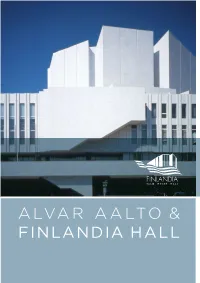

ALVAR AALTO & Finlandia HALL

ALVAR AALTO & FinLAnDiA HALL ALVAR AALTO & FinlanDiA hall To be able to understand the architecture of Finlandia Hall, one must be familiar with the larger vision of Helsinki of which Finlandia Hall is only a part, a vision that may never fully materialize. At the beginning of the 19th century, Helsinki was granted the position of capital of the newly established Grand Duchy of Fin- land, and the architect Carl Ludvig Engel designed the monumen- tal central square, known today as the Senate Square, which is flanked by the Cathedral, Senate Palace and the University. Alvar Aalto was of the opinion that independent Finland should con- Alvar Aalto in the 1930’s, Photo: Heinonen, struct a central square of its own in the new centre of the city, Alvar Aalto -museum which is in the vicinity of the Parliament House, the building that symbolizes the status won in 1917. lt was a lucky coincidence that right in front of the Parliament there lay a large railway freight yard which was to be re-sited elsewhere; Aalto thought that this area would provide a unique opportunity for the realization of an idea, originally suggested by Eliel Saarinen in 1917, for the con- struction of a new traffic route called Freedom Avenue (Vapau- denkatu) from the northern suburbs right to the heart of the city. Aalto envisaged a large, fan-shaped square terraced on three levels the topmost point of which would be where the equestrian statue of Mannerheim now stands. The square would open towards Töölönlahti Bay, and on one side it would be flanked by a concert and congress hall and further on by an opera house, an art mu- seum, the city library and, possibly, other public buildings, which would be erected in the midst of the greenery of Hesperia Park. -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

CV-Axel Straschnoy-IPERCUBO

Axel Straschnoy Born in Buenos Aires, 1978. Lives and works in Helsinki. Education 2008-2009 Le Pavillon, Palais de Tokyo. 2005 Visual Art Seminar. Centro Cultural Rojas/UBA. 2005 Kuvataideakatemia, Helsinki. 2001-2003 Contemporary Art Seminar by Mónica Girón. 2002-2003 Sculpture Workshop by Miguel Harte. 2000-2005 BA in Art History, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Public collections Kiasma, Helsinki. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. Rauma Art Museum, Rauma. Fundación arteBA, Buenos Aires. National Art Archive, Helsinki. Solo exhibitions 2019 The Finnish Astronautical Society, Forum Box, Helsinki. Float, Andrée Polarcenter Grenna Museum, Gränna 2016 Hoy, / ¡gran mañana!, / en los pinos soplan vientos / del pasado, Del Infinito Arte, Buenos Aires. Le rappel à l’ordre, Forum Box, Helsinki. Neomylodon Listai Ameghino, Inter Arts Center, Malmö 2015 Neomylodon Listai Ameghino, Galleria Augusta, Helsinki. Neomylodon Listai Ameghino, Evolutionsmuseet, Uppsala. La Figure de la Terre, Museo del Cine, Buenos Aires 2014 La Figure de la Terre, Del Infinito Arte, Buenos Aires. 2013 Kilpisjärvellä, Mirta Demare Gallery, Rotterdam. Opening Archive, Ateneum Museum Library, Helsinki. 2012 Kilpisjärvellä, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. 2011 How to Build a Dishwasher, Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo. Boxes, Muu, Helsinki. 2010 How to Build a Dishwasher, Kerava Art Museum, Kerava. Opening / Prints, Koh-i-noor, Copenhagen How to Build a Dishwasher, Kaiku Galleria, Helsinki. 2009 Axel Straschnoy, Galerie Xippas, Paris Opening, Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki. Opening, Salon Light/SP, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo. 2007 Camera, MAA-TILA, Helsinki. 2006 Los Proyectos Medley Taller Boceto, Galería Dabbah Torrejón, Buenos Aires. Group exhibitions 2015 Del Infinito Arte, arteBA, Buenos Aires. -

Helsinki, Finland

S WEDEN © 2011 maps.com © 2011 NORWAY Helsinki Pohjoisesplanadi 35 HELSINKI a e S i c l t B a Helsinki, Finland POLAND PORT EXPLORER and SHOPPING GUIDE Look for this sign or flag VAT Most stores participate in the Value Added Tax program in which Non-European citi- in all of our preferred zens may be entitled to reclaim a portion or all of the taxes paid (depending on the total pur- shops. chase price). It is your responsibility to inquire as to whether or not the store participates in VAT refund program if the purchase qualifies for a refund. GENERAL INFORMATION Beware of “similar” signs Helsinki is the capital of Finland, of ways of serving Reindeer, one of which is cold and smoked. Bear at store fronts. GLOBAL BLUE Shop where you see this Global Blue - Tax Free Shop- situated on a peninsula on the southern coast, overlooking the Gulf and Elk may appear on the menu and there is also plenty of ‘game’. ping sign and ask for your tax refund receipt. To qualify, there are minimum of Finland and the Baltic Sea. It is a predominantly modern city with The Finns enjoy pastries and desserts, a particular favorite being the If the store is not men- amounts, per store, per day, so please ask the retailer for details. Show your a population of half a million inhabitants. Little remains of the original Cloudberry, found extensively in northern Scan di navia, it is a varia- tioned on this map, then purchases and Global Blue receipts to Customs officials when leaving the old town, this is largely due to the fact that the first buildings were tion of the Raspberry, slightly more tart. -

2ND ANNOUNCEMENT · CALL for ABSTRACTS Invitation

2ND ANNOUNCEMENT · CALL FOR ABSTRACTS Invitation EWMA In cooperation with the Finnish Wound Care Society (FWCS), European Wound Management Association EWMA is pleased to announce the 19th Conference of the The Executive Committee Marco Romanelli, President European Wound Management Association on the theme: Zena Moore, Honorary Secretary & President Elect Luc Gryson, Treasurer Sue Bale, Recorder HEALING, EDUCATING, Council Members Paulo Alves LEARNING and PREVENTING Jan Apelqvist Carol Dealey in wound care Finn Gottrup Marcus Gürgen Maarten J. Lubbers Severin Läuchli The conference gives the participants an opportunity to benefit Sylvie Meaume from high level scientific presentations, network with each E. Andrea Nelson Patricia Price other, exchange data and evaluate clinical practice. Salla Seppänen José Verdú Soriano Rita Gaspar Videira Peter Vowden The conference will be held in Helsinki, Finland at Helsinki Address Exhibition and Convention Centre, which is located in EWMA Business Office Itä-Pasila, a modern urban complex within easy reach c/o Congress Consultants Martensens Allé 8 of the city centre. DK-1828 Frederiksberg C Denmark The participants will therefore not only benefit from the Tel.: +45 7020 0305 Fax: +45 7020 0315 scientific aspect of the conference but also from [email protected] the beautiful location of the conference. www.ewma2009.org We look forward to welcoming you to Helsinki. Sue Bale, EWMA Recorder Marco Romanelli, EWMA President Salla Seppänen, FWCS President Preliminary Programme The programme will consist of plenary sessions, key sessions, work- shops and satellite symposia. The sessions will deal with advancement of education and research in relation to epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis, prevention and management of wounds.