School District Origins Kern County California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libraries Connected by the End of Year

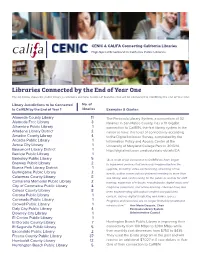

CENIC & CALIFA Connecting California Libraries High-Speed Broadband in California Public Libraries Libraries Connected by the End of Year One The list below shows the public library jurisdictions and total number of branches that will be connected to CalREN by the end of Year One. Library Jurisdictions to be Connected No. of to CalREN by the End of Year 1 libraries Examples & Quotes: Alameda County Library 11 The Peninsula Library System, a consortium of 32 Alameda Free Library 3 libraries in San Mateo County, has a 10 Gigabit Alhambra Public Library 1 connection to CalREN, the first library system in the Altadena Library District 2 nation to have this level of connectivity according Amador County Library 4 to the Digital Inclusion Survey, completed by the Arcadia Public Library 1 Information Policy and Access Center at the Azusa City Library 1 University of Maryland College Park in 2013/14, Beaumont Library District 1 http://digitalinclusion.umd.edu/state-details/CA. Benicia Public Library 1 Berkeley Public Library 5 “As a result of our connection to CalREN we have begun Brawley Public Library 2 to implement services that were only imagined before the Buena Park Library District 1 upgrade, including: video-conferencing; streaming of live Burlingame Public Library 2 events; author conversations delivered remotely to more than Calaveras County Library 8 one library; web-conferencing for the public as well as for staff Camarena Memorial Public Library 2 training; expansion of e-books, e-audiobooks, digital music and City of Commerce Public Library 4 magazine collections, and online learning. Libraries have also Colusa County Library 8 been experimenting with patron-created and published Corona Public Library 1 content, such as digital storytelling and maker spaces. -

Club Directory And

Club Directory and Athletic Record :Pool~.... " 14\~~~~ ~--~~ ' ' lt' ... "~)'.., '• ,,/"-: f HO '~~~~::}::~·~' fp University of ~i¥nesota. De f.!t . p ~ '1 s ~ :l ·;, / 1.::::: rJ vc "'' C ' • ,, h ,_ { _ 1 ---( ! /c-..l 'r <.: f 4 ~" YJ ! \.., (,..,.. I <.... e"' ,...J "" Your Attention, Please This is the first revised edition of the combined University of Minnesota athletic records book and the University of Minnesota "M" Club membership directory. After nearly 12 months of effort and three mailed appeals to the entire "M" membership we finally had about a 65 per cent return on the information forms sent out. We had to do the best we could with available information in complet ing the directory section. This booklet is financed in its entirety by the Department of Physical Education and Athletics as a service to the "M" Club and to news outlets desiring a record of Minnesota's past athletic contests, and is made possible through the co operation and assistance of Ike Armstrong, Director. We remind you that a complete file of "M" members is kept in room 208 Cooke Hall at the University. If you at any time have information which will help keep these files up to date, it will be greatly appreciated. OTIS DYPWICK, Sports Information Director, Handbook Editor. STAFF MEMBERS IKE J. ARMSTRONG, B.S., Director RICHARD J. DoNNELLY, Ph.D., Assistant Director Baseball Edna Gustafson Richard Siebert, B.A., Coach Lorinne Bergman Darlene Marjamaa Basketball John A. Kundla, M.E., Coach Physical Education Glen A. Reed, B.S., Assistant Richard J. Donnelly, Ph.D., Professor Ralph A. -

FY 2011-2012 Recommended Budget: Kern County Administrative Office

CountyCounty ofof KernKern FYFY 2011-122011-12 RecommendedRecommended BudgetBudget COUNTY OF KERN COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE RECOMMENDED BUDGET FY 2011-12 Submitted by John Nilon County Administrative Officer BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Jon McQuiston Supervisor District 1 Zack Scrivner Supervisor District 2 Mike Maggard Supervisor District 3 Raymond A. Watson Supervisor District 4 Karen Goh Supervisor District 5 KERN COUNTY SUPERVISORIAL DISTRICTS ELECTORATE OF KERN COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE PUBLIC PUBLIC HEALTH AND CULTURE, EDUC. & PUBLIC WAYS & GENERAL PROTECTION ASSISTANCE SANITATION RECREATION FACILITIES KERN MEDICAL PUBLIC HEALTH CLERK OF THE ASSESSOR- DISTRICT FIRE HUMAN SERVICES LIBRARY ROADS ATTORNEY DEPARTMENT CENTER SERVICES BOARD RECORDER EMPLOYERS' ENVIRONMENTAL MENTAL HEALTH PARKS AND INFORMATION AUDITOR SHERIFF- PUBLIC TRAINING HEALTH AIRPORTS TECHNOLOGY CONTROLLER- CORONER DEFENDER RESOURCE SERVICES RECREATION SERVICES COUNTY CLERK EMERGENCY PROBATION AGRICULTURE AND VETERANS MEDICAL SERVICES FARM AND HOME GENERAL WASTE ELECTIONS DEPARTMENT MEASUREMENT SERVICE ADVISOR SERVICES STANDARDS MANAGEMENT PLANNING AND ANIMAL CONTROL GRAND JURY AGING & ADULT ENGINEERING TREASURER - TAX COMMUNITY SERVICES AND SURVEY DEVELOPMENT SERVICES COLLECTOR CHILD SUPPORT SERVICES COUNTY COUNSEL PERSONNEL DEVELOPMENT SERVICES AGENCY BOARD OF TRADE LEGEND FULL ACCOUNTABILITY TO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS FISCAL ACCOUNTABILITY TO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS ELECTIVE OFFICE PREPARED BY: COUNTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE, JULY 2011 TABLE -

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report Prepared by Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners for Tulare County Association of Govenments 11 February 2008 Executive Summary As part of an agreement with the Tulare County Association of Governments, Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners (TBWP) visited nine potential riparian and wildlife corridors in Tulare County during summer 2007. We developed a numerical ranking system and determined the five corridors with highest potential for conservation, recreation and conjunctive uses. The selected corridors include: Deer Creek Riparian Corridor, Kings River Riparian Corridor, Oaks to Tules Riparian Corridor, Lewis Creek Riparian Corridor, and Cottonwood Creek Wildlife Corridor. For each corridor, we provide a brief description and a summary of attributes and opportunities. Opportunities include flood control, groundwater recharge, recreation, tourism, and wildlife. We also provide a brief description of opportunities for an additional eight corridors that were not addressed in depth in this document. In addition, we list the Measure R transportation improvements and briefly discuss the potential wildlife impacts for each of the projects. The document concludes with an examination of other regional planning efforts that include Tulare County, including the San Joaquin Valley Blueprint, the Tulare County Bike Path Plan, the TBWP’s Sand Ridge-Tulare Lake Plan, the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), and the USFWS Upland Species Recovery Plan. Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners, 2/11/2008 Page 2 of 30 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Goals and Objectives………………………...……………………………………………. 4 Tulare County Corridors……………………..……………………………………………. 5 Rankings………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Corridors selected for Detailed Study…………………………………………….. 5 Deer Creek Corridor………………………………………………………. 5 Kings River Corridor……………………………………………………… 8 Oaks to Tules Corridor…………………………………..………………… 10 Lewis Creek East of Lindsay……………………………………………… 12 Cottonwood Creek………………………………………...………………. -

East Bakersfield

Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian & Bicycle Safety for the Community of East Bakersfield October 2017 Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian & Bicycle Safety for the Community of East Bakersfield By Austin Hall, Tony Dang, Wendy Ortiz, California Walks; Jill Cooper, Katherine Chen, Ana Lopez, UC Berkeley Safe Transportation Research & Education Center (SafeTREC) Introduction At the invitation of the Kern County Department of Public Health, the University of California at Berkeley’s Safe Transportation Research and Education Center (SafeTREC) and California Walks (Cal Walks) facilitated a community-driven pedestrian and bicycle safety action-planning workshop in East Bakersfield to improve pedestrian safety, bicycle safety, walkability, and bikeability across the East Bakersfield community. Prior to the workshop, Cal Walks staff conducted an in-person site visit on Friday, July 14, 2017, to adapt the Community Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety Training program curriculum to meet the local communities’ needs and to provide context-sensitive example strategies for the community’s existing conditions. Cal Walks facilitated the workshop on August 22, 2017, which consisted of: 1) an overview of multidisciplinary approaches to improve pedestrian and bicycle safety; 2) three walkability and bikeability assessments along three routes; and 3) small group action-planning discussions to facilitate the development of community-prioritized recommendations to inform East Bakersfield’s active transportation efforts. This report summarizes the workshop proceedings, as well as ideas identified during the process and recommendations for pedestrian and bicycle safety projects, policies, and programs. Background Community Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety Training Program The Community Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety Training (CPBST) program is a joint project of UC Berkeley SafeTREC and Cal Walks. -

4. Environmental Impact Analysis 4. Cultural Resources

4. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS 4. CULTURAL RESOURCES 4.4.1 INTRODUCTION The following section addresses the proposed Project’s potential to result in significant impacts upon cultural resources, including archaeological, paleontological and historic resources. On September 20, 2013, the South Central Coastal Information Center (SCCIC) and the Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County were contacted to conduct a records search for cultural resources within the Project Site at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street and immediate Project vicinity. The analysis presented below is based on the record search results provided from the SCCIC, dated October 2, 2013, and written correspondence from The Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, dated October 18, 2013. Correspondences from both agencies are included in Appendix E to this Draft EIR. 4.4.2 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Description of the Study Area The Project Site is located at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street. The Project Site also includes the closure of an at- grade crossing at the intersection of Railroad Avenue and 13th Street. The portion of the Project Site that extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University is located in an area of primarily undeveloped land within the city limits of Santa Clarita. -

Real Time Arrival Information Using the Farebox How to Plan Your Trip

Real Time Arrival Information How to Plan Your Trip Smart phones: Use the Golden Empire Transit Start by finding your destination on the Free App for iphones and androids System Map located in the middle of the Computers/tablets: Go to getbus.org book. Regular phones: Using the number on the GET offers trip planning at getbus.org. stop, call 869-2GET (2438) and put in the stop Next, find the starting point where you will number. board the bus. To speak with a Customer Service Representa- Decide which route or routes you need to take. tive, call 869-2GET (2438) Some trips require more than one bus, which Customer Service Representatives are on duty means you will need to transfer from one bus Monday through Friday from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 to another. If you will need to transfer, find the intersection of the two routes. This is where you p.m. and on Saturday and Sunday from 6:30 will exit the first bus and board the second. a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Check the schedule to determine what time GET now offers Real Time Information on you need to arrive at your bus stop. The buses computers and mobile devices travel through the schedule from left to right. Computer/Tablets: Click on real time infor- Choose the timetable section that refers to mation at getbus.org. Choose a route. Hold the direction you will be traveling, for example the clicker over a stop (red dot) for location Route 21- Bakersfield College/Eastbound. -

The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan Promotes a More Efficient

CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS – VERSION 5 CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS INTRODUCTION This chapter sets forth plans of action for the region to pursue and meet identified transportation needs and issues. Planned investments are consistent with the goals and policies of the plan, the Sustainable Community Strategy element (see chapter 4) and must be financially constrained. These projects are listed in the Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) and are modeled in the Air Quality Conformity Analysis. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes Forecast modeling methods in this Regional Transportation a more efficient transportation Plan primarily use the “market-based approach” based on demographic data and economic trends (see chapter 3). The system that calls for fully forecast modeling was used to analyze the strategic funding alternative investments in the combined action elements found in this transportation modes, while chapter.. emphasizing transportation demand and transporation Alternative scenarios are not addressed in this document; they are, however, addressed and analyzed for their system management feasibility and impacts in the Environmental Impact Report approaches for new highway prepared for the 2014 Regional Transportation Plan, as capacity. required by the California Environmental Quality Act (State CEQA Guidelines Sections 15126(f) and 15126.6(a)). From this point, the alternatives have been predetermined and projects that would deliver the most benefit were selected. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes a more efficient transportation system that calls for fully funding alternative transportation modes, while emphasizing transportation demand and transporation system management approaches for new highway capacity. The Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) includes projects that move the region toward a financially constrained and balanced system. -

Emergency 30 Day Substitue Teacher

Office of Mary C. Barlow Kern County Superintendent of Schools Credentials Office: 1330 Truxtun Avenue (Corner of Truxtun Ave & L St) (661) 636-4197 Advocates for Children RETIRED CREDENTIALED TEACHER SUBSTITUTE APPLICATION PROCESS The holder of a valid teaching credential authorizes the holder to serve as a day-to-day substitute teacher in any classroom, including preschool, kindergarten, and grades 1-12 inclusive. The holder may serve as a substitute for no more than 30 days for any one teacher during the school year, except in a special education classroom, where the holder may serve for no more than 20 days for any one teacher during the school year. However, if the substitute teacher and the teacher of record hold the same credential and authorization for the assignment the substitute teacher may serve on a long term assignment. To apply, complete the application process following the steps in the order listed below: #1) Contact the KCSOS Credentials Office to determine your eligibility. The Credentials Office is available by email at [email protected] or by phone at 661-636-4197. #2) Schedule a Live Scan (Fingerprint) appointment online through the KCSOS Human Resources website: www.kern.org/hr; click on Live Scan/Fingerprint Appointments #3) Report to the Credentials Office (Enter through the Credentials Office door to the right) for your live scan appointment with the following: Credit or Debit Card to pay live scan processing fees and a valid government issued picture I.D. Live Scan Request form(s) – obtain from the KCSOS Credentials Office Information Necessary for Substitute Teaching form #4) When you receive your fingerprint clearance form, schedule an appointment online with the KCSOS Credentials Office at (https://kern.org/credentialing/credentialing-office/) to submit the following: Copy of valid teaching/services credential KCSOS County-Wide Fingerprint Clearance form (1/2 sheet received by mail approx. -

Askia Booker

Table of contents Basketball Practice Facility .....................................IFC 2010-11 REVIEW.....................................................47 vs. Ranked Opponents............................................198, 199 Quick Facts.......................................................................2 Results & Leaders............................................................48 Win/Loss Streaks..........................................................199 Media Information .............................................................3 Statistics ........................................................................49 Coaching Records...........................................................200 Pac-12 Conference.............................................................4 Game-by-Game Team Statistics ..........................................50 Coaches Year-by-YeaR......................................................201 Pac-12 Conference Schedule................................................5 Season Highs & Lows.......................................................51 Record Breakdown.........................................................202 Box Scores.................................................................52-64 Milestone Wins..............................................................203 2011-2012 Opponents ..............................................6, 7, 8 Season Highlights ...........................................................64 Year-by-YeaR Offensive Stats ............................................204 -

Attempted Sexual Assault Reported at BC Newly Elected BCSGA Officers

Possible league title in bc_rip The Renegade Rip Grand opening of sight for BC softball @bc_rip @bc_rip Studio Movie Grill Sports, Page 7 www.therip.com News, Page 2 The Renegade Rip Vol. 90 ∙ No. 6 Bakersfield College Thursday, April 19, 2018 Attempted Newly elected BCSGA officers for sexual assault 2018-2019 have big plans for future By Issy Barrientos Reporter A few weeks ago, Bakersfield College held its Student Government Asso- reported at BC ciation elections to vote in the new officers for the next school year. The new president and vice-president are James Tompkins and Ashely Nicole Harp. By Hector Martinez Bakersfield College, explained that Tompkins joined BCSGA because he not only wanted his voice, and the Reporter for the moment, all the information voices of other students heard, but also the voice of former incarcerated stu- Public Safety had on the matter was dents. He has been a part of BCSGA for a year now as senator. As a senator he On April 10, Bakersfield Col- included in the email alert sent to was able to pass a resolution to have staff on campus complete bias training so lege’s Public Safety sent out an alert the campus community that day. that they can see pass their own biases. As the president he would like continue about an incident that happened in- Counts also explained that there to expand on his work for incarcerated students. side the women’s restroom of the are sometimes several incidents in a “I still think there are a lot of barriers for education for people that are deal- Humanities building. -

An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Government Documents and Publications First Nations Era 3-10-2017 2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810" (2017). Government Documents and Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the First Nations Era at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government Documents and Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken and John R. Johnson March 2005 FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP, INC. 2727 Del Rio Place, Suite A, Davis, California, 95616 http://www.farwestern.com 530-756-3941 Prepared for Caltrans Contract No. 06A0148 & 06A0391 For individuals with sensory disabilities this document is available in alternate formats. Please call or write to: Gale Chew-Yep 2015 E. Shields, Suite 100 Fresno, CA 93726 (559) 243-3464 Voice CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. and John R. Johnson Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Submitted by: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. 2727 Del Rio Place, Davis, California, 95616 Submitted to: Valerie Levulett Environmental Branch California Department of Transportation, District 5 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 Contract No.