210 the Banqueting House and the Masque of Augurs: Architecture And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strand Walk Lma.Pdf

LGBTI HERITAGE WALK OF WHITEHALL Trafalgar’s Queer • In a 60 minute walk from Trafalgar Square to Aldwych you’ll have a conversation with Oscar Wilde, meet a transsexual Olympian, discover a lesbian ménage a trois in Covent Garden, find a transgender traffic light, walk over Virginia Woolf, and learn about Princess Seraphina who was less of a princess and more of a queen. • It takes about an hour and was devised and written by Andy Kirby. Directions – The walk starts at the statue This was the site of the Charing Cross, one of of King Charles I at the south side of the Eleanor Crosses commemorating Edward I’s Trafalgar Square. first wife. The replica is outside Charing Cross Station. Distances from London are measured here, where stood the pillory where many gay men were locked, mocked and punished. The Stop 1 – Charing Cross picture is of a similar incident in Cheapside. On 25 September 2009 Ian Baynham died following a homophobic attack in the square. Joel Alexander, 20, and Ruby Thomas, 19, were imprisoned for it. Directions – Walk to the front of the National At the top of these steps in the entrance to the Gallery on the north side of Trafalgar Square National Gallery are Boris Anrep’s marble mosaics directly in front of you. laid between 1928 and 1952. Two lesbian icons are the film star Greta Garbo as Melpomene, Muse of Stop 2 – National Gallery & Portrait Gallery Tragedy and Bloomsbury writer Virginia Woolf wielding an elegant pen as Clio, Muse of History. To the right of this building is the National Portrait Gallery with pictures and photographs of Martina Navratilova, K D Lang, Virginia again, Alan Turing, Harvey Milk and Joe Orton. -

London View Management Framework SPG MP26

26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to 219 Horse Guards Road 424 The St James’s Park area was originally a marshy water meadow, before being drained to provide a deer park for Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. The current form of the park owes much to Charles II, who ordained a new layout, incorporating The Mall, in the 1660s. The park was remodelled by John Nash in 1827-8 and his layout survives largely intact. St James’s Park is maintained to an extremely high standard and the bridge across the lake provides a frequently visited place from which to appreciate views through the Park. The landscape is subtly lit after dark. St James’s Park is included on English Heritage’s Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest at Grade I. 425 There is one Viewing Location at St James’ Park 26A, which is situated on the east side of the bridge over the lake. 220 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 26A St James’s Park Bridge N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 26A.1 St James’s Park Bridge – near the centre of the bridge 26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to Horse Guards Road 221 Description of the View 426 The Viewing Location is on the east side of the footbridge Landmarks include: across the lake. The bridge was built in 1956-7 to the designs Whitehall Court (II*) of Eric Bedford of the Ministry of Works. Views vary from Horse Guards (I) either end of the bridge and a near central location has been The Foreign Office (I) selected for the single Assessment Point (26A.1) orientated The London Eye towards Horse Guards Parade. -

Wren and the English Baroque

What is English Baroque? • An architectural style promoted by Christopher Wren (1632-1723) that developed between the Great Fire (1666) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). It is associated with the new freedom of the Restoration following the Cromwell’s puritan restrictions and the Great Fire of London provided a blank canvas for architects. In France the repeal of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 revived religious conflict and caused many French Huguenot craftsmen to move to England. • In total Wren built 52 churches in London of which his most famous is St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711). Wren met Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in Paris in August 1665 and Wren’s later designs tempered the exuberant articulation of Bernini’s and Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture in Italy with the sober, strict classical architecture of Inigo Jones. • The first truly Baroque English country house was Chatsworth, started in 1687 and designed by William Talman. • The culmination of English Baroque came with Sir John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) and Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), Castle Howard (1699, flamboyant assemble of restless masses), Blenheim Palace (1705, vast belvederes of massed stone with curious finials), and Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight (now in ruins). Vanburgh’s final work was Seaton Delaval Hall (1718, unique in its structural audacity). Vanburgh was a Restoration playwright and the English Baroque is a theatrical creation. In the early 18th century the English Baroque went out of fashion. It was associated with Toryism, the Continent and Popery by the dominant Protestant Whig aristocracy. The Whig Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham, built a Baroque house in the 1720s but criticism resulted in the huge new Palladian building, Wentworth Woodhouse, we see today. -

The Ghost Bus Tour Route Record

APPENDIX A: LONDON SERVICE PERMIT LSP0666 THE GHOST BUS TOUR ROUTE RECORD Effective from 31 July 2017 STREETS TRAVERSED Route 1: From/to Northumberland Avenue via City Northumberland Avenue (westbound), Charing Cross, Whitehall (southbound), Parliament Street (southbound), Parliament Square (east, south, west and north sides), Parliament Street (northbound), Whitehall (northbound), Charing Cross, Strand, Aldwych, Drury Lane, Russell Street, Catherine Street, Aldwych, Fleet Street, Fetter Lane, New Fetter Lane, Holborn Circus, Holborn Viaduct, Giltspur Street (northbound), West Smithfield, Giltspur Street (southbound), Newgate Street, King Edward Street, Angel Street, St Martins le Grand, Cheapside, Poultry, Mansion House Street, King William Street, Monument Street, Fish Street Hill, Lower Thames Street, Byward Street, Tower Hill, Tower Bridge Approach, Tower Bridge, Tower Bridge Road, Tooley Street, Duke Street Hill, Borough High Street, Southwark Street, Blackfriars Road, Blackfriars Bridge, Victoria Embankment, Northumberland Avenue. Alternative route As main route to Fleet Street at Fetter Lane, then continue via Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus, Ludgate Hill, St Paul’s Churchyard, Cannon Street, Queen Victoria Street, Mansion House Street, then as main route. Route 2: From/to Northumberland Avenue via West End Northumberland Avenue (westbound), Charing Cross (circumnavigate King Charles Island), Northumberland Avenue (eastbound), Victoria Embankment (southbound), Horseguards Avenue, Whitehall, Charing Cross, Trafalgar Square (south side), -

Legal Notices a Copy of the Petition Will Be Supplied by the Under- the COMPANIES ACT 1948 Signed on Payment of the Prescribed Charge

THE LONDON GAZETTE, SlsT MARCH 1981 4659 VALE ROYAL DISTRICT COUNCIL Copies of the Order, statement of reasons and relevant plans may be inspected free of charge, at all reasonable HIGHWAYS ACT 1980, SECTION 14 hours from 31st March to 16th May 1981 at the Council The District of Vale Royal (Northwich Internal By-Pass Offices, Church Street, Northwich, the Council Offices, A 559 Chesterway Phase III Classified Road) (Side Roads) Whitehall, School Lane, Hartford and also at the Depart- Order 1981. ment of Transport, North-West Region, Sunley Buildings. Notice is hereby given that the Vale Royal District Council Piccadilly Plaza, Manchester. hereby give notice that they have made and submitted Any person wishing to make representations or objections to the Secretary of State for the Enviroment and Trans- to the confirmation of the Order may do so in writing port for confirmation an Order under section 14 of the before 16th May 1981, to the Minister of Transport at Highways Act 1980 and of all other enabling powers the office of the Regional Controller (Roads and Trans- which will authorise the Council: portation), North-West Region, Sunley Buildings, Piccadilly (a) To carry out the improvement of highways. Plaza, Manchester Ml 4BE, stating the grounds of (b) To stop-up highways. objection. (c) To construct a new highway which shall be a road. W. R. T. Woods, Chief Executive Officer and Secretary (d) To stop-up a private means of access to premises. (e) To provide a new means of access to premises. Council Offices, All on or in the vicinity of the route of the classified Whitehall, School Lane, road which the Council are proposing to construct between Hartford, Northwich. -

Queen's House Conference 2017 European Court Culture

Queen’s House Conference 2017 European Court Culture & Greenwich Palace, 1500-1750 RCIN405291, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017 Thursday to Saturday, 20-22 April 2017 Location: National Maritime Museum and the Queen’s House, Greenwich Conference organisers: Janet Dickinson (University of Oxford), Christine Riding (Royal Museums Greenwich) and Jonathan Spangler (Manchester Metropolitan University). With support from the Society for Court Studies. For queries about the programme, please: [email protected] For bookings: call 020 8312 6716 or e-mail [email protected] Booking form: http://www.rmg.co.uk/see-do/exhibitions-events/queens-house- conference-2017 Thursday, 20 April 12.30–13.00 Registration 13.00–15.00 Introduction, conference organisers Jemma Field, Brunel University: Greenwich Palace and Anna of Denmark: Royal Precedence, Royal Rituals, and Political Ambition Karen Hearn, University College London): “‘The Queenes Picture therein’: Henrietta Maria amid architectural magnificence” Anna Whitelock, Royal Holloway, University of London: Title to be confirmed 15.00–15.30 Coffee and tea 15.30 17.00 Christine Riding, Royal Museums Greenwich: Private Patronage, Public Display: The Armada Portraits and Tapestries, and Representations of Queenship Natalie Mears, Durham University: Tapestries and paintings of the Spanish Armada: Culture and Horticulture in Elizabethan and Jacobean England Charlotte Bolland, National Portrait Gallery: The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I 17.00–18.00 Keynote lecture Simon Thurley, Institute of Historical Research, London: Defining Tudor Greenwich: landscape, religion and industry 1 18.00–19.00 Wine reception in the Queen’s House, followed by dinner at restaurant in Greenwich, at own expense. -

GOSLING Pp01-13.V2:Layout 3

GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 21.07.2009 12:23 Uhr Seite 1 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 2 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 3 CLASSIC DESIGN FOR CONTEMPORARY INTERIORS With contributions by Stephen Calloway, Jean Gomm, Tim Gosling and Jürgen Huber Foreword by Tim Knox, Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London Photography by Ray Main PRESTEL MUNICH BERLIN LONDON NEW YORK GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 4 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 5 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 6 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 7 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 8 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 9 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 10 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 21.07.2009 12:23 Uhr Seite 11 Foreword 13 1 The Classical Tradition 14 2 Space, Scale and Light 24 3 Commissioning 42 4 The Art and Craft of Luxury marquetry · mirror and glass · vellum · shagreen · leather lacquer · gilding · eglomise · inlays · accessories 52 5 The Art of Technology 170 6 Contemporary Design in Classic Interiors 192 Keepers of the Flame: Expert Craftsmen 216 Contributors 217 Selected Bibliography 218 Acknowledgements and Photo Credits 220 Index 221 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 12 GOSLING_pp01-13.v2:Layout 3 09.07.2009 11:57 Uhr Seite 13 Foreword direct link between today’s designers and craftsmen and their Acounterparts in the past is an important one. -

Section II: Summary of the Periodic Report on the State of Conservation, 2006

State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties in Europe SECTION II workmanship, and setting is well documented. UNITED KINGDOM There are firm legislative and policy controls in place to ensure that its fabric and character and Maritime Greenwich setting will be preserved in the future. b) The Queen’s House by Inigo Jones and plans for Brief description the Royal Naval College and key buildings by Sir Christopher Wren as masterpieces of creative The ensemble of buildings at Greenwich, an genius (Criterion i) outlying district of London, and the park in which they are set, symbolize English artistic and Inigo Jones and Sir Christopher Wren are scientific endeavour in the 17th and 18th centuries. acknowledged to be among the greatest The Queen's House (by Inigo Jones) was the first architectural talents of the Renaissance and Palladian building in England, while the complex Baroque periods in Europe. Their buildings at that was until recently the Royal Naval College was Greenwich represent high points in their individual designed by Christopher Wren. The park, laid out architectural oeuvres and, taken as an ensemble, on the basis of an original design by André Le the Queen’s House and Royal Naval College Nôtre, contains the Old Royal Observatory, the complex is widely recognised as Britain’s work of Wren and the scientist Robert Hooke. outstanding Baroque set piece. Inigo Jones was one of the first and the most skilled 1. Introduction proponents of the new classical architectural style in England. On his return to England after having Year(s) of Inscription 1997 travelled extensively in Italy in 1613-14 he was appointed by Anne, consort of James I, to provide a Agency responsible for site management new building at Greenwich. -

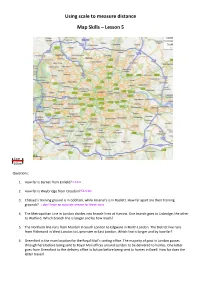

Using Scale to Measure Distance Map Skills – Lesson 5

Using scale to measure distance Map Skills – Lesson 5 1cm 10km Questions: 1. How far is Barnet from Enfield? 2. How far is Weybridge from Croydon? 3. Chelsea’s training ground is in Cobham, while Arsenal’s is in Radlett. How far apart are their training grounds? 4. The Metropolitan Line in London divides into branch lines at Harrow. One branch goes to Uxbridge, the other to Watford. Which branch line is longer and by how much? 5. The Northern line runs from Morden in South London to Edgware in North London. The District line runs from Richmond in West London to Upminster in East London. Which line is longer and by how far? 6. Greenford is the main location for the Royal Mail’s sorting office. The majority of post in London passes through here before being sent to Royal Mail offices around London to be delivered to homes. One letter goes from Greenford to the delivery office in Sutton before being sent to homes in Ewell. How far does the letter travel? The map below zooms in on the area of Westminster. 1cm 75m QUESTIONS: 1. The Houses of Parliament is shown by its proper name of the Palace of Westminster on this map. How far does the Prime Minister have to travel to get from 10 Downing Street to Parliament? 2. Horse Guards Parade will be the venue of the Beach Volleyball at this summer’s Olympic Games. How far is it from Charing Cross station? 3. How long is Westminster Bridge? 4. A walking tour of the government buildings starts at Big Ben, goes up Parliament St and Whitehall, along Northumberland Avenue, and back down the Victoria Embankment. -

Middle Saxon and Later Archaeological Remains in Whitehall

MIDDLE SAXON AND LATER ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS IN WHITEHALL Paw Jorgensen With contributions by Jonathan Butler, Kevin Hayward, Chris Jarrett and Kevin Rielly SUMMARY Guards Road to the west, the Embankment to the east, Parliament Square to the south Archaeological investigations undertaken during the and Great Scotland Yard to the north (Figs streetscape improvements in Whitehall revealed the 2, 2a, 2b). Bordering upon the site are remains of several periods of activity. Middle Saxon governmental offices, mostly dating to the activity most likely associated with that previously late 19th and 20th centuries, many of which found at the Old Treasury Building in the 1960s was are Listed Buildings. In total 78 Listed revealed on Whitehall opposite the west end of Horse Buildings are located immediately adjacent Guards Avenue. Elsewhere masonry associated with to the site; of these, 14 are Grade I listed, York Place, the Archbishop of York’s official residence 17 Grade II* listed, and 47 Grade II listed; in London, and Whitehall Palace was found. Later these include Queen Mary’s Steps, the Ban- remains consisted of buildings which were constructed queting House, the Ministry of Defence in the 18th and 19th century following the destruction Main Building, and the Cabinet Office, Privy of Whitehall Palace in two fires at the end of the 17th Council and Treasury Building, all of which century. to varying degrees have incorporated part of the fabric of Whitehall Palace into the INTRODUCTION current buildings and structures. Furthermore, the entire site lies within the Pre-Construct Archaeology was commiss- Lundenwic and Thorney Island Area of Spec- ioned by Atkins Heritage acting on behalf ial Archaeological Priority and immediately of the City of Westminster to undertake a to the south is the World Heritage Site of watching-brief during streetscape improve- Westminster Palace, Westminster Abbey and ments along Whitehall and the adjoining St Margaret’s Church (WHS number 462). -

The Old War Office Building

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The Old War Office Building A history The Old War Office Building …a building full of history Foreword by the Rt. Hon Geoff Hoon MP, Secretary of State for Defence The Old War Office Building has been a Whitehall landmark for nearly a century. No-one can fail to be impressed by its imposing Edwardian Baroque exterior and splendidly restored rooms and stairways. With the long-overdue modernisation of the MOD Main Building, Defence Ministers and other members of the Defence Council – the Department’s senior committee – have moved temporarily to the Old War Office. To mark the occasion I have asked for this short booklet, describing the history of the Old War Office Building, to be published. The booklet also includes a brief history of the site on which the building now stands, and of other historic MOD headquarters buildings in Central London. People know about the work that our Armed Forces do around the world as a force for good. Less well known is the work that we do to preserve our heritage and to look after the historic buildings that we occupy. I hope that this publication will help to raise awareness of that. The Old War Office Building has had a fascinating past, as you will see. People working within its walls played a key role in two World Wars and in the Cold War that followed. The building is full of history. Lawrence of Arabia once worked here. I am now occupying the office which Churchill, Lloyd-George and Profumo once had. -

The Great Plague 1665- 1666 How Did London Respond to It?

The National Archives Education Service The Great Plague 1665- 1666 How did London respond to it? London scenes of the Plague 1665-1666 – Museum of London The Great Plague 1665-1666 How did London respond? Introduction Lesson at a Glance The Plague This was the worst outbreak of plague in England since the black death Suitable For: KS3 of 1348. London lost roughly 15% of its population. While 68,596 deaths were recorded in the city, the true number was probably over Time Period: 100,000. Other parts of the country also suffered. Early Modern 1485-1750 The earliest cases of disease occurred in the spring of 1665 in a parish outside the city walls called St Giles-in-the-Fields. The death rate Curriculum Link: began to rise during the hot summer months and peaked in September The development of when 7,165 Londoners died in one week. Church, state and society Rats carried the fleas that caused the plague. They were attracted by in Britain 1509-1745 city streets filled with rubbish and waste, especially in the poorest areas. Society, economy and culture across the period Those who could, including most doctors, lawyers and merchants, fled Learning Objective: the city. Charles II and his courtiers left in July for Hampton Court and then Oxford. Parliament was postponed and had to sit in October at Oxford, the increase of the plague being so dreadful. Court cases were To closely examine a also moved from Westminster to Oxford. document in order to discover information. The Lord Mayor and aldermen (town councillors) remained to enforce the King’s orders to try and stop the spread of the disease.