Middle Saxon and Later Archaeological Remains in Whitehall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafalgar Square & Parliament Square Garden Activities and Hires

FM Internal Guidance – Trafalgar Square & Parliament Square Garden Activities and Hires The GLA do not permit (unless in exceptional circumstances in which GLA authorisation has been given in writing): • Private or exclusive parties/functions • ‘Roadshow’ activities which only have giveaways as the primary content of the event • ‘Flash mob’ activity • Overt branding and/or advertising within the event – however, there is scope for commercial activity • Offensive or adult themed materials in any printed format or computer generated/screened format. • Handouts or giveaways without an accompanying event • Infrastructure or dressing which may damage the fabric of the Trafalgar Square • Infrastructure on any part of Parliament Square Garden • Vehicle focused events on a pedestrian space - cars, motorbikes or double decker buses as the focus for example. • Busking without an accompanying event/ purpose • Use of balloons or inflatables • Use of stickers or any adhesive material • Any act which is against the Bye Laws and/or PRSR 2011 act • Pyrotechnics, candles or any other element requiring a naked flame for ignition or that gives out sparks or smoke. • Balloon releases • Drones • Any licensable activity at any time throughout an event or hire without prior written authorisation of the GLA. Further detail 1. Sports tournament – Parliament square is in the centre of very busy roads and Trafalgar Square is surrounded on three sides by busy roads. The GLA cannot accommodate a full sports match because of the safety issues. They also conflict with the byelaws and impact public access around the square. We can accommodate sports activations as a low-key press call. 2. Cigarette/alcohol & gambling activations – The GLA does not support advertising of as this would contradict all current policy and health initiatives that the GLA is driving forward for Londoners. -

Strand Walk Lma.Pdf

LGBTI HERITAGE WALK OF WHITEHALL Trafalgar’s Queer • In a 60 minute walk from Trafalgar Square to Aldwych you’ll have a conversation with Oscar Wilde, meet a transsexual Olympian, discover a lesbian ménage a trois in Covent Garden, find a transgender traffic light, walk over Virginia Woolf, and learn about Princess Seraphina who was less of a princess and more of a queen. • It takes about an hour and was devised and written by Andy Kirby. Directions – The walk starts at the statue This was the site of the Charing Cross, one of of King Charles I at the south side of the Eleanor Crosses commemorating Edward I’s Trafalgar Square. first wife. The replica is outside Charing Cross Station. Distances from London are measured here, where stood the pillory where many gay men were locked, mocked and punished. The Stop 1 – Charing Cross picture is of a similar incident in Cheapside. On 25 September 2009 Ian Baynham died following a homophobic attack in the square. Joel Alexander, 20, and Ruby Thomas, 19, were imprisoned for it. Directions – Walk to the front of the National At the top of these steps in the entrance to the Gallery on the north side of Trafalgar Square National Gallery are Boris Anrep’s marble mosaics directly in front of you. laid between 1928 and 1952. Two lesbian icons are the film star Greta Garbo as Melpomene, Muse of Stop 2 – National Gallery & Portrait Gallery Tragedy and Bloomsbury writer Virginia Woolf wielding an elegant pen as Clio, Muse of History. To the right of this building is the National Portrait Gallery with pictures and photographs of Martina Navratilova, K D Lang, Virginia again, Alan Turing, Harvey Milk and Joe Orton. -

Character Overview Westminster Has 56 Designated Conservation Areas

Westminster’s Conservation Areas - Character Overview Westminster has 56 designated conservation areas which cover over 76% of the City. These cover a diverse range of townscapes from all periods of the City’s development and their distinctive character reflects Westminster’s differing roles at the heart of national life and government, as a business and commercial centre, and as home to diverse residential communities. A significant number are more residential areas often dominated by Georgian and Victorian terraced housing but there are also conservation areas which are focused on enclaves of later housing development, including innovative post-war housing estates. Some of the conservation areas in south Westminster are dominated by government and institutional uses and in mixed central areas such as Soho and Marylebone, it is the historic layout and the dense urban character combined with the mix of uses which creates distinctive local character. Despite its dense urban character, however, more than a third of the City is open space and our Royal Parks are also designated conservation areas. Many of Westminster’s conservation areas have a high proportion of listed buildings and some contain townscape of more than local significance. Below provides a brief summary overview of the character of each of these areas and their designation dates. The conservation area audits and other documentation listed should be referred to for more detail on individual areas. 1. Adelphi The Adelphi takes its name from the 18th Century development of residential terraces by the Adam brothers and is located immediately to the south of the Strand. The southern boundary of the conservation area is the former shoreline of the Thames. -

HOLBA-Insights-Report-Jul-20.Pdf

HEART OF LONDON JULY AREA PERFORMANCE HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE CONTENTS JULY 2020 EDITION INTRODUCTION 02 Welcome to our area performance report. This monthly summary provides trends in footfall, spending SUMMARY ANALYSIS 03 and much more, in the Heart of London area. Focusing on Leicester Square, Piccadilly Circus, Haymarket, Piccadilly and FOOTFALL TRENDS 04 St James’s, find out exactly how our area has performed FOOTFALL OVERVIEW 05 throughout the month. HOURLY FOOTFALL 06 The report is available exclusively to members, and explores REGIONAL FOOTFALL 07 changes in trends that impact the performance of our area, allowing your business to plan with confidence and make the COVID-19 AND FOOTFALL 08 most of being in the heart of London. YOUR FEEDBACK IS IMPORTANT TO US PROPERTY & INVESTMENT 09 PLEASE CLICK ON THE BUTTON INVESTMENT 10 TO REQUEST NEW DATA OR ANALYSIS PROPERTY PERFORMANCE 11 LEASE AVAILABILITY 12 EVENTS & ACTIVITY 13 IMPACT CALENDAR 14 GLOSSARY 15 See our Glossary for more detail on data sources and definitions. 2 HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE SUMMARY ANALYSIS – JULY 2020 Rainfall (mm) 2020 2019 500K 25 YEAR ON YEAR FOOTFALL 450K -72% Footfall in the current month compared to the same month last year 400K 20 350K 300K 15 MONTH ON MONTH FOOTFALL 250K +97% Footfall in the current month compared Footfall 200K 10 to the previous month Rainfall (mm) Rainfall 150K 100K 5 YEAR TO DATE FOOTFALL 50K -58% Footfall in the current year to date K 0 compared to the same period last year M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 Week 28 Week 29 Week 30 Week 31 July trend summary • Like-for-like footfall in the Heart of London area was down 72% in July 2020 compared to the same month last year. -

London View Management Framework SPG MP26

26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to 219 Horse Guards Road 424 The St James’s Park area was originally a marshy water meadow, before being drained to provide a deer park for Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. The current form of the park owes much to Charles II, who ordained a new layout, incorporating The Mall, in the 1660s. The park was remodelled by John Nash in 1827-8 and his layout survives largely intact. St James’s Park is maintained to an extremely high standard and the bridge across the lake provides a frequently visited place from which to appreciate views through the Park. The landscape is subtly lit after dark. St James’s Park is included on English Heritage’s Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest at Grade I. 425 There is one Viewing Location at St James’ Park 26A, which is situated on the east side of the bridge over the lake. 220 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 26A St James’s Park Bridge N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 26A.1 St James’s Park Bridge – near the centre of the bridge 26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to Horse Guards Road 221 Description of the View 426 The Viewing Location is on the east side of the footbridge Landmarks include: across the lake. The bridge was built in 1956-7 to the designs Whitehall Court (II*) of Eric Bedford of the Ministry of Works. Views vary from Horse Guards (I) either end of the bridge and a near central location has been The Foreign Office (I) selected for the single Assessment Point (26A.1) orientated The London Eye towards Horse Guards Parade. -

The Ghost Bus Tour Route Record

APPENDIX A: LONDON SERVICE PERMIT LSP0666 THE GHOST BUS TOUR ROUTE RECORD Effective from 31 July 2017 STREETS TRAVERSED Route 1: From/to Northumberland Avenue via City Northumberland Avenue (westbound), Charing Cross, Whitehall (southbound), Parliament Street (southbound), Parliament Square (east, south, west and north sides), Parliament Street (northbound), Whitehall (northbound), Charing Cross, Strand, Aldwych, Drury Lane, Russell Street, Catherine Street, Aldwych, Fleet Street, Fetter Lane, New Fetter Lane, Holborn Circus, Holborn Viaduct, Giltspur Street (northbound), West Smithfield, Giltspur Street (southbound), Newgate Street, King Edward Street, Angel Street, St Martins le Grand, Cheapside, Poultry, Mansion House Street, King William Street, Monument Street, Fish Street Hill, Lower Thames Street, Byward Street, Tower Hill, Tower Bridge Approach, Tower Bridge, Tower Bridge Road, Tooley Street, Duke Street Hill, Borough High Street, Southwark Street, Blackfriars Road, Blackfriars Bridge, Victoria Embankment, Northumberland Avenue. Alternative route As main route to Fleet Street at Fetter Lane, then continue via Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus, Ludgate Hill, St Paul’s Churchyard, Cannon Street, Queen Victoria Street, Mansion House Street, then as main route. Route 2: From/to Northumberland Avenue via West End Northumberland Avenue (westbound), Charing Cross (circumnavigate King Charles Island), Northumberland Avenue (eastbound), Victoria Embankment (southbound), Horseguards Avenue, Whitehall, Charing Cross, Trafalgar Square (south side), -

Postscript Layout 1

14 Established 1961 Tuesday, December 10, 2019 Business LuLu’s Twenty14 Holdings completes GBP 300 million investment in the UK Iconic Great Scotland Yard Hotel, London inaugurated LONDON: Twenty14 Holdings, the hospitality investment essence, we have curated an unmatched experience for every arm of LuLu Group International has completed investments guest while recreating the historic premises into a symbol of of £300 million in UK, with the inauguration of the Great ultimate hospitality. We welcome you to experience this unique Scotland Yard in London yesterday. The hotel will be open and fabulous experience at the Great Scotland Yard.” for business from December 9, 2019. The historic property An 1820s Grade II listed building with Edwardian & was acquired in 2015 for Rs. 1,025 crores, and the makeover Victorian architecture, the high-end luxury boutique hotel of the hotel involved a further Rs. 512 crores. In addition to with 7 floors and spanning 93,000 sq.ft. has 153 rooms and the Great Scotland Yard, Twenty14 Holdings had acquired 15 suites apart from a 2-bedroom townhouse VIP-suite cre- the celebrated Waldorf Astoria Edinburgh - The Caledonian ated from part of the original Scotland Yard Police premises. in Scotland in 2018. The hotel also features a library, gymnasium, meeting/con- The Great Scotland Yard Hotel, which is being managed by ference rooms, a 120-seater conference space/ballroom and Hyatt under their The Unbound Collection by Hyatt brand, is VIP function rooms. located in the St. James’s district of Westminster. The Unbound Adeeb Ahamed, Managing Director, Twenty14 Holdings, said Collection by Hyatt brand is a portfolio of independent hotel “The Great Scotland Yard Hotel is a dream come true for us. -

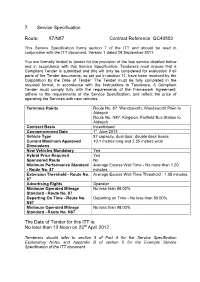

7. Service Specification Route

7. Service Specification Route: 87/N87 Contract Reference QC40803 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Route No. 87: Wandsworth, Wandsworth Plain to Aldwych Route No. N87: Kingston, Fairfield Bus Station to Aldwych Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 1st June 2013 Vehicle Type 87 capacity, dual door, double deck buses Current Maximum Approved 10.1 metres long and 2.55 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.20 - Route No. 87 minutes Extension Threshold - Route No. Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 1.05 minutes 87 Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. 87 Departing On Time - Route No. Departing on Time - No less than 85.00% N87 Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. -

Legal Notices a Copy of the Petition Will Be Supplied by the Under- the COMPANIES ACT 1948 Signed on Payment of the Prescribed Charge

THE LONDON GAZETTE, SlsT MARCH 1981 4659 VALE ROYAL DISTRICT COUNCIL Copies of the Order, statement of reasons and relevant plans may be inspected free of charge, at all reasonable HIGHWAYS ACT 1980, SECTION 14 hours from 31st March to 16th May 1981 at the Council The District of Vale Royal (Northwich Internal By-Pass Offices, Church Street, Northwich, the Council Offices, A 559 Chesterway Phase III Classified Road) (Side Roads) Whitehall, School Lane, Hartford and also at the Depart- Order 1981. ment of Transport, North-West Region, Sunley Buildings. Notice is hereby given that the Vale Royal District Council Piccadilly Plaza, Manchester. hereby give notice that they have made and submitted Any person wishing to make representations or objections to the Secretary of State for the Enviroment and Trans- to the confirmation of the Order may do so in writing port for confirmation an Order under section 14 of the before 16th May 1981, to the Minister of Transport at Highways Act 1980 and of all other enabling powers the office of the Regional Controller (Roads and Trans- which will authorise the Council: portation), North-West Region, Sunley Buildings, Piccadilly (a) To carry out the improvement of highways. Plaza, Manchester Ml 4BE, stating the grounds of (b) To stop-up highways. objection. (c) To construct a new highway which shall be a road. W. R. T. Woods, Chief Executive Officer and Secretary (d) To stop-up a private means of access to premises. (e) To provide a new means of access to premises. Council Offices, All on or in the vicinity of the route of the classified Whitehall, School Lane, road which the Council are proposing to construct between Hartford, Northwich. -

St M Newsletter No 3 Final

the church on Parliament Square by kind permission of Clare Weatherill NEWS No 3 Winter 2017 news and features from St Margaret’s LENT 2017 PRE-LENTEN ART EXHIBITION AT ST MARGARET’S Lent may originally have followed Sacred Space: drawings and paintings by Lottie Stoddart Epiphany, just as Jesus’ sojourn in the wilderness followed Over the course of 2016 I was given the immediately on his baptism, but it wonderful opportunity to spend an intensive soon became firmly attached to period drawing inside Westminster Abbey. My Easter, as the principal occasion first visit, following in the footsteps of William for baptism and for the Blake, was with the Royal Drawing School, and reconciliation of those who had formed the idea of returning and engaging with been excluded from the Church’s the Abbey's interior for a longer period. My work investigates spaces that evoke the fellowship. sacred. My previous works on this theme have This history explains the included London graveyards, ancient characteristic notes of Lent – self- woodlands and most recently tree veneration examination, penitence, self-denial, in India. Many evocations of Westminster study, and preparation for Easter. Abbey concentrate on the monumental, but I Ashes are an ancient sign of penitence; have sought out the personal and intimate from the middle ages it became the where visual juxtapositions have occurred custom to begin Lent by being marked through time, architectural style and changing in ash with the sign of the Cross. use. The Abbey's central shrine and surrounding chapels have made me consider The calculation of the forty how sacred spaces are glimpsed, hidden and days of Lent has varied considerably in revealed. -

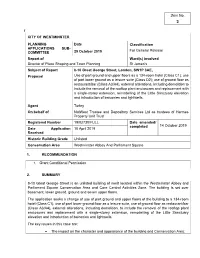

Item No. 2 F CITY of WESTMINSTER PLANNING APPLICATIONS SUB- COMMITTEE Date 29 October 2019 Classification for General Release Re

Item No. 2 f CITY OF WESTMINSTER PLANNING Date Classification APPLICATIONS SUB- For General Release COMMITTEE 29 October 2019 Report of Ward(s) involved Director of Place Shaping and Town Planning St James's Subject of Report 8-10 Great George Street, London, SW1P 3AE, Proposal Use of part ground and upper floors as a 134-room hotel (Class C1); use of part lower ground as a leisure suite (Class D2); use of ground floor as restaurant/bar (Class A3/A4), external alterations, including demolition to include the removal of the rooftop plant enclosures and replacement with a single-storey extension, remodelling of the Little Sanctuary elevation and introduction of balconies and lightwells. Agent Turley On behalf of NatWest Trustee and Depository Services Ltd as trustees of Hermes Property Unit Trust Registered Number 19/02730/FULL Date amended/ completed 14 October 2019 Date Application 10 April 2019 Received Historic Building Grade Unlisted Conservation Area Westminster Abbey And Parliament Square 1. RECOMMENDATION 1. Grant Conditional Permission 2. SUMMARY 8-10 Great George Street is an unlisted building of merit located within the Westminster Abbey and Parliament Square Conservation Area and Core Central Activities Zone. The building is set over basement, lower ground, ground and seven upper floors. The application seeks a change of use of part ground and upper floors of the building to a 134-room hotel (Class C1), use of part lower-ground floor as a leisure suite, use of ground floor as restaurant/bar (Class A3/A4), external alterations, including demolition, to include the removal of the rooftop plant enclosures and replacement with a single-storey extension, remodelling of the Little Sanctuary elevation and introduction of balconies and lightwells. -

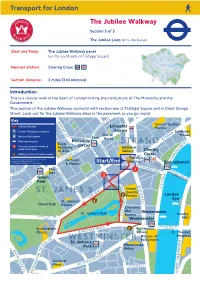

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park.