Chapter 3. Development of Alternative Policy Scenarios for RE Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jersey Energy Trends 2018 Report

Energy Trends 2018 Statistics Jersey: www.gov.je/statistics Overview This report examines supply and use of energy in Jersey through the importation, distribution and consumption of fuels such as petroleum products and electricity. The focus of the report is on energy supply and use in 2018. Figures are also presented for calendar years 2014 to 2017. Longer term trends, going back to 1991, are shown for road fuel consumption and for electricity importation and generation. The energy data presented in this report provides the basis for calculating carbon emissions for Jersey. Through the UK, Jersey is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol; the document “Pathway 2050: An Energy Plan for Jersey”11outlines how the Island intends to reduce its carbon emissions in line with the commitments of the UK and other European nations. Jersey’s energy data is submitted annually to the compilers of the UK’s national greenhouse gas inventory, Aether, who independently verify and validate the data using internationally agreed methodologies. The resultant emissions calculated for Jersey are published by Aether2 and submitted to the international inventories as part of the UK’s national inventory. Summary for 2018 Supply • almost all of Jersey’s energy supply was imported; about 2% was produced on-Island as electricity generated by the Energy from Waste Facility • petroleum products accounted for almost two-thirds (63%) of Jersey’s energy supply; electricity (imported and on-Island generated) accounted for the remainder (37%) • Jersey’s total primary energy -

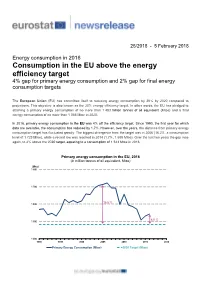

Consumption in the EU Above the Energy Efficiency Target 4% Gap for Primary Energy Consumption and 2% Gap for Final Energy Consumption Targets

25/2018 - 5 February 2018 Energy consumption in 2016 Consumption in the EU above the energy efficiency target 4% gap for primary energy consumption and 2% gap for final energy consumption targets The European Union (EU) has committed itself to reducing energy consumption by 20% by 2020 compared to projections. This objective is also known as the 20% energy efficiency target. In other words, the EU has pledged to attaining a primary energy consumption of no more than 1 483 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) and a final energy consumption of no more than 1 086 Mtoe in 2020. In 2016, primary energy consumption in the EU was 4% off the efficiency target. Since 1990, the first year for which data are available, the consumption has reduced by 1.7%. However, over the years, the distance from primary energy consumption target has fluctuated greatly. The biggest divergence from the target was in 2006 (16.2%, a consumption level of 1 723 Mtoe), while a record low was reached in 2014 (1.7%, 1 509 Mtoe). Over the last two years the gap rose again, to 4% above the 2020 target, equating to a consumption of 1 543 Mtoe in 2016. Primary energy consumption in the EU, 2016 (in million tonnes of oil equivalent, Mtoe) (Mtoe) 1 800 1 700 15.5 % 1 600 4.0 % 1 500 1 400 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 Primary Energy Consumption (Mtoe) 2020 Target (Mtoe) In 2016, final energy consumption in the EU was 1 108 Mtoe, 2.0% above the efficiency target. -

Full Report – BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019 | 68th edition Contents Introduction For 66 years, Natural the BPgas Statistical Review of WorldRenewable energy 1 Group chief executive’s introductionEnergy 3has 0 Reserves provided high-quality objective 5 1 andRenewables consumption 2 2018 at a glance globally 3consistent 2 Production data on world energy 52 markets. Generation by source 3 Group chief economist’s analysisThe review 3 4 Consumption is one of the most widely respected 5 3 Biofuels production and authoritative 3 7 Prices publications in the field of energy 3 8 Trade movements Electricity Primary energy economics, used for reference by the media, 8 Consumption 5 4 Generation 9 Consumption by fuel academia, Coalworld governments and energy 56 Generation by fuel 12 Consumption per capita companies. 4 2 Reserves A new edition is published every June. 44 Production CO2 Carbon Oil 45 Consumption 5 7 Carbon dioxide emissions 1 4 Reserves Discover more 47 onlinePrices and trade movements 1 6 Production All the tables and charts found in the latest printed Key minerals edition are available at bp.com/statisticalreviewNuclear energy 20 Consumption plus a number of extras, including: 5 8 Production • The energy charting tool – view 4 8 Consumption 2 4 Prices predetermined reports or chart specific data 59 Reserves 2 6 Refining according to energy type, region, country 59 Prices and year. Hydroelectricity 2 8 Trade movements • Historical data from 1965 for many sections. • Additional data 4 9for refinedConsumption oil production Appendices demand, natural gas, coal, hydroelectricity, nuclear energy and renewables. 6 0 Approximate conversion factors • PDF versions and PowerPoint slide packs of 6 0 Definitions the charts, maps and graphs, plus an Excel workbook of the data. -

Annexes A.1 A

World Energy Council 2013 World Energy Resources: Annexes A.1 A Annexes Contents 1. Abbreviations and Acronyms / page 2 2. Conversion Factors and Energy Equivalents / page 5 3. Definitions / page 6 A.2 World Energy Resources: Annexes World Energy Council 2013 1. Abbreviations and Acronyms 103 kilo (k) CMM coal mine methane 106 mega (M) CNG compressed natural gas 9 10 giga (G) CO2e carbon dioxide equivalent 1012 tera (T) COP3 Conference of the Parties III, Kyoto1997 1015 peta (P) cP centipoise 1018 exa (E) CSP centralised solar power 1021 zetta (Z) d day ABWR advanced boiling water reactor DC direct current AC alternating current DHW domestic hot water AHWR advanced heavy water reactor DOWA deep ocean water applications API American Petroleum Institute ECE Economic Commission for Europe APR advanced pressurised reactor EIA U.S. Energy Information Administration / environmental impact assessment APWR advanced pressurised water reactor EOR enhanced oil recovery b/d barrels per day EPIA European Photovoltaic Industry Association bbl barrel EPR European pressurised water reactor bcf billion cubic feet ESTIF European Solar Thermal Industry Federation bcm billion cubic metres ETBE ethyl tertiary butyl ether BGR Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe F Fahrenheit billion 109 FAO UN Food and Agriculture Organization BIPV building integrated PV FBR fast breeder reactor BNPP buoyant nuclear power plant FID final investment decision boe barrel of oil equivalent FSU former Soviet Union BOO build, own, operate ft feet BOT build, operate, -

Conversion Factors and Unit Abbreviations

Conversion factors Key World Energy Statistics Conversion factors and unit abbreviations General conversion factors for energy To: TJ Gcal Mtoe MBtu GWh From: multiply by: TJ 1 2.388 x 102 2.388 x10-5 9.478 x 102 2.778 x 10-1 Gcal 4.187 x 10-3 1 1.000 x 10-7 3.968 1.163 x 10-3 Mtoe 4.187 x 104 1.000 x 107 1 3.968 x 107 1.163 x 104 MBtu 1.055 x 10-3 2.520 x 10-1 2.520 x 10-8 1 2.931 x 10-4 GWh 3.600 8.598 x 102 8.598 x 10-5 3.412 x 103 1 Conversion factors for mass To: kg t lt st lb From: multiply by: kilogramme (kg) 1 1.000 x 10-3 9.842 x 10–4 1.102 x 10–3 2.205 tonne (t) 1.000 x 103 1 9.842 x 10–1 1.102 2.205 x 103 long ton (lt) 1.016 x 103 1.016 1 1.120 2.240 x 103 short ton (st) 9.072 x 102 9.072 x 10–1 8.929 x 10–1 1 2.000 x 103 pound (lb) 4.536 x 10–1 4.536 x 10–4 4.464 x 10–4 5.000 x 10–4 1 Conversion factors for volume To: gal U.S. gal U.K. bbl ft3 l m3 From: multiply by: U.S. gallon (gal) 1 8.327 x 10-1 2.381 x 10-2 1.337 x 10-1 3.785 3.785 x 10-3 U.K. -

Econ 366 – Energy Economics Fall 2012

Econ 366 – Energy Economics Fall 2012 Measuring Energy / Energy Data Energy Data Sources • Alberta Data: Energy Resources Conservation Board • Canadian Data: Statistics Canada (Cansim), Natural Resources Canada Office of Energy Efficiency, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) • International Data: US Department of Energy (USDOE), Energy Information Administration (EIA), International Energy Agency (IEA), British Petroleum (BP) • Many other data sources; some (Platts for example) require registration and/or subscriptions Measuring Energy • Value – $20 worth of gas; $80 worth of electricity • Natural units – 5 litres of gas; 30 cubic metres of n.g (at a standard pressure and temperature of 101.325 kPa and 15°C ); a cord of wood; a ton of coal • Calorific value – KwH; GJ / tonne; MJ / m3 – 4.184 Joules = 1 calorie • Commercial units / Product Equivalence – Ktoe; tce (less ‘precise’ than calorific value since oil, coal not uniform) • unit converter http://www.iea.org/stats/unit.asp Scientific Notation Term Value Scientific notation kilo thousand 103 mega million 106 giga billion 109 thousand tera 1012 billion peta million billion 1015 Exa billion billion 1018 Metric / Imperial Conversions (ERCB) Metric Imperial 1 kilojoule = 0.948213 British thermal units 1 m3 (oil)* = 6.2929 Cdn barrels of oil 1 m3 (ethane) = 6.3301 Cdn barrels of ethane 1 m3 (gas) = 35.49373 cubic feet of gas 1 m3 (propane) = 6.3 Cdn barrels of propane 0.984206 long tons (2240 lbs) = tonne 1.102311 short tons (2000 lbs) * See ERCB for temperatures / pressures -

Important Conversion Factors in Petroleum Technology Conversion

1183 Important Conversion Factors in Petroleum Technology Conversion Table 1 Oil volume and mass To convert . ... Into Tonnes (metric) Kiloliters Barrels US gallons Tonnes/yrb Tonnes (metric) 1 1=SGa 6:2898=SGa 264:17=SGa – Kiloliters 1SGa 1 6:2898 264:17 – Petroleum barrels 0:159 SGa 0:159 1 42 – US gallons 0:0038 SGa 0:0038 0:0238 1 – Barrels/dayb – – – – 58:03 SGa a SG D specific gravity of the oil @ 15:55 ıC b For converting between mass and volume, some sources use an assume or average density. That can be misleading and is not best practice Table 2 Flow/consumption ratios To convert . ... Into Multiply by Standard cubic feet per barrel (scf=bbl) Normal cubic meters per cubic meter (Nm3=m3) 0:178 Table 3 Geothermal gradients To convert . ... Into Multiply by ıC=100 m ıF=100 ft 0:549 Table 4 Density To convert . ... Into Use the formula API gravity Specific gravity @ 60 ıF(sp.gr.) API gravity D .141:5=sp.gr./ 131:5 Specific gravity @ 60 ıF(sp.gr.) API gravity sp.gr. D 141:5=.API gravity C 131:5/ Table 5 Vol um e To convert . ... Into Multiply by Standard cubic feet (scf) of gas @ 60 ıF and 14:73 psi Standard cubic meters (Sm3)@15ıC and 101:325 kPa 0:0283058 Standard cubic meters (Scm) of gas @ 15 ıC Normal cubic meters (Nm3)@0ıC and 101:325 kPa 1:0549000 and 1:0325 kPa In considering industrial gases, especially when negotiating contracts, it is crucial to know the difference between standard and normal. -

Approximate Conversion Factors

Approximate conversion factors Statistical Review of World Energy Crude oil* To convert Tonnes (metric) Kilolitres Barrels US gallons Tonnes/year From Multiply by Tonnes (metric) 1 1.165 7.33 307.86 – Kilolitres 0.8581 1 6.2898 264.17 – Barrels 0.1364 0.159 1 42 – US gallons 0.00325 0.0038 0.0238 1 – Barrels/day – – – – 49.8 *Based on the worldwide average gravity Products To convert Barrels to Tonnes to Kilolitres to Tonnes to Tonnes to Tonnes to tonnes barrels tonnes kilolitres gigajoules barrels oil equivalent From Multiply by Ethane 0.059 16.850 0.373 2.679 49.400 8.073 Liquified petroleum gas (LPG) 0.086 11.600 0.541 1.849 46.150 7.542 Gasoline 0.120 8.350 0.753 1.328 44.750 7.313 Kerosene 0.127 7.880 0.798 1.253 43.920 7.177 Gas oil/diesel 0.134 7.460 0.843 1.186 43.380 7.089 Residual fuel oil 0.157 6.350 0.991 1.010 41.570 6.793 Product basket 0.124 8.058 0.781 1.281 43.076 7.039 Approximate conversion factors – Statistical Review of World Energy – updated July 2021 Page | 1 Natural gas and LNG To convert Billion cubic Billion cubic Petajoules Million Million Trillion Million metres NG feet NG NG tonnes oil tonnes LNG British barrels oil equivalent thermal equivalent units From Multiply by 1 billion cubic metres NG 1.000 35.315 36.000 0.860 0.735 34.121 5.883 1 billion cubic feet NG 0.028 1.000 1.019 0.024 0.021 0.966 0.167 1 petajoule NG 0.028 0.981 1.000 0.024 0.021 0.952 0.164 1 million tonnes oil equivalent 1.163 41.071 41.868 1.000 0.855 39.683 6.842 1 million tonnes LNG 1.360 48.028 48.747 1.169 1.000 46.405 8.001 1 trillion -

Energy and Transportation

ENERGY AND TRANSPORTATION ENERGY REQUIREMENT ENERGY SUPPLY ENERGY INTENSITY ELECTRICITY GENERATION NUCLEAR ENERGY RENEWABLE ENERGY OIL PRODUCTION OIL PRICES TRANSPORT GOODS TRANSPORT PASSENGER TRANSPORT ROAD FATALITIES ENERGY AND TRANSPORTATION • ENERGY REQUIREMENT ENERGY SUPPLY An analysis of energy problems requires a Total primary energy supply comprehensive presentation of basic supply and demand Annual growth in percentage data for all fuels in a manner which allows the easy comparison of the contribution that each fuel makes to the economy and their interrelationships through the conversion of one fuel into another. This type of presentation is suitable for the study of energy substitution, energy conservation and forecasting. Definition The table refers to total primary energy supply (TPES). TPES equals production plus imports minus exports minus international bunkers plus or minus stock changes. The International Energy Agency energy balance methodology is based on the calorific content of the energy commodities and a common unit of account. The unit of account adopted is the tonne of oil equivalent (toe) which is defined as 107 kilocalories (41.868 gigajoules). This quantity of energy is, within a few per cent, equal to the net heat content of one tonne of crude oil. The difference between the “net” and the “gross” calorific value for each fuel is the latent heat of vaporisation of the water produced during combustion of the fuel. For coal and oil, net calorific value is about 5% Statlink http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932707914 less than gross, for most forms of natural and manufactured gas the difference is 9-10%, while for electricity there is no difference. -

Jersey Energy Trends 2019 Report

Energy Trends 2019 Statistics Jersey: www.gov.je/statistics Overview This report examines supply and use of energy in Jersey through the importation, distribution and consumption of fuels such as petroleum products and electricity. The focus of the report is on energy supply and use in 2019. Figures are also presented for calendar years 2015 to 2018. Longer term trends, going back to 1993, are shown for road fuel consumption and for electricity importation and generation. The energy data presented in this report provides the basis for calculating carbon emissions for Jersey. Through the UK, Jersey is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol; the document “Pathway 2050: An Energy Plan for Jersey”11outlines how the Island intends to reduce its carbon emissions in line with the commitments of the UK and other European nations. A long-term climate action plan will be developed in 2021 setting out Jersey’s journey to carbon neutrality. Jersey’s energy data is submitted annually to the compilers of the UK’s national greenhouse gas inventory, Aether, who independently verify and validate the data using internationally agreed methodologies. The resultant emissions calculated for Jersey are published by Aether2 and submitted to the international inventories as part of the UK’s national inventory. Summary for 2019 Supply • Almost all of Jersey’s energy supply was imported; about 2% was produced on-Island as electricity generated by the Energy Recovery Facility and solar panels. • Petroleum products accounted for almost two-thirds (62%) of Jersey’s energy supply; electricity (imported and on-Island generated) accounted for the remainder (38%). -

Approximate Conversion Factors

Approximate conversion factors Statistical Review of World Energy Crude oil* To convert Tonnes (metric) Kilolitres Barrels US gallons Tonnes/year From Multiply by Tonnes (metric) 1 1.165 7.33 307.86 - Kilolitres 0.8581 1 6.2898 264.17 - Barrels 0.1364 0.159 1 42 - US gallons 0.00325 0.0038 0.0238 1 - Barrels/day - - - - 49.8 *Based on the worldwide average gravity Products To convert Barrels to tonnes Tonnes to barrels Kilolitres to tonnes Tonnes to kilolitres From Multiply by Liquified petroleum gas (LPG) 0.086 11.60 0.542 1.844 Gasoline 0.120 8.35 0.753 1.328 Kerosene 0.127 7.88 0.798 1.253 Gas oil/diesel 0.134 7.46 0.843 1.186 Residual fuel oil 0.157 6.35 0.991 1.010 Product basket 0.125 7.98 0.788 1.269 Approximate conversion factors - Statistical Review of World Energy Page | 1 Natural gas and LNG To convert Billion cubic Billion cubic Million tonnes Million tonnes Trillion British Million barrels metres feet oil equivalent LNG thermal units oil equivalent NG NG From Multiply by 1 billion cubic metres NG 1 35.3 0.9 0.74 35.7 6.16 1 billion cubic feet NG 0.028 1 0.025 0.021 1.01 0.17 1 million tonnes oil equivalent 1.11 39.2 1 0.82 39.7 6.84 1 million tonnes LNG 1.36 48.0 1.22 1 48.6 8.37 1 trillion British thermal units 0.028 0.99 0.025 0.021 1 0.17 1 million barrels oil equivalent 0.16 5.74 0.15 0.12 5.80 1 Units 1 metric tonne = 2204.62 lb = 1.1023 short tons 1 kilolitre = 6.2898 barrels 1 kilolitre = 1 cubic metre 1 kilocalorie (kcal) = 4.187 kJ = 3.968 Btu 1 kilojoule (kJ) = 0.239 kcal = 0.948 Btu 1 British thermal unit (Btu) -

Overview of Energy Usage in the United States and the World

CHAPTER ONE Overview of Energy Usage in the United States and the World To begin, take a moment to stop and listen. Try to observe Understanding Energy all sounds: the tick of a clock, the hum of a computer, the whirl of a passing car, the whisper of a heater, or perhaps Energy, by definition, is the ability to do work on a physi- the growl of an airplane overhead. These sounds, so com- cal system. Yet, what does this really mean? Since energy is mon that they often go unnoticed, would likely sound the capacity to do work, one must first understand the con- thunderous to societies living 200 years ago. What makes cept of work. Work is defined as force multiplied by dis- society today so different from those historical societies? tance. A force alone is not enough to constitute work; it must be combined with a movement, a term equivalent to The answer is simple: fossil fuel. The availability of easily accessible and cheap energy has the distance component of the equation. Consider the breathed technological life into society. It has influenced example of someone pushing a shopping cart and running the way we transport ourselves, the houses we live in, the into a wall. No matter how hard this person pushes the cart offices we work in, the classrooms we study in, and even the or how much force he or she exerts, if the cart is not chang- food we eat. Energy has single-handedly changed the face ing position then no work is being done.