Modular Script System: Atmospheric Chemistry and Air Pollution Brandenburg Technical University D-03044 Cottbus, POB 10 13 44 Univ.-Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 61 Winter 2012 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Prof A T Dronsfield, School of Education, | Prof J Betteridge (Twickenham, Middlesex) Health and Sciences, University of Derby, | Dr N G Coley (Open University) Derby, DE22 1GB [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr C J Cooksey (Watford, Hertfordshire) Secretary: | Prof E Homburg (University of Maastricht) Prof W P Griffith, Department of Chemistry, | Prof F James (Royal Institution) Imperial College, South Kensington, London, | Dr D Leaback (Biolink Technology) SW7 2AZ [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr P J T Morris (Science Museum) Treasurer; Membership Secretary: | Prof. J. W. Nicholson (University of Greenwich) Dr J A Hudson, Graythwaite, Loweswater, | Mr P N Reed (Steensbridge, Herefordshire) Cockermouth, Cumbria, CA13 0SU | Dr V Quirke (Oxford Brookes University) [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr S Robinson (Ham, Surrey) Newsletter Editor: | Prof. H. Rzepa (Imperial College) Dr A Simmons, Epsom Lodge, | Dr. A Sella (University College) La Grande Route de St Jean,St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Production: Dr G P Moss, School of Biological and Chemical, Sciences Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp Contents From the Editor 2 RSC Historical Group News - Bill Griffith 3 Identification Query - W. H. Brock 4 Members’ Publications 5 NEWS AND UPDATES 6 USEFUL WEBSITES AND ADDRESSES 7 SHORT ESSAYS 9 The Copperas Works at Tankerton - Chris Cooksey 9 Mauveine - the final word? (3) - Chris Cooksey and H. -

2017 Stevens Helen 1333274

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Paradise Closed Energy, inspiration and making art in Rome in the works of Harriet Hosmer, William Wetmore Story, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Elizabeth Gaskell and Henry James, 1847-1903 Stevens, Helen Christine Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Paradise Closed: Energy, inspiration and making art in Rome in the works of Harriet Hosmer, William Wetmore Story, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Elizabeth Gaskell and Henry James, 1847-1903 Helen Stevens 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD King’s College London September, 2016 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... -

Historical Development of the Periodic Classification of the Chemical Elements

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIODIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEMICAL ELEMENTS by RONALD LEE FFISTER B. S., Kansas State University, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree FASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physical Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 196A Approved by: Major PrafeLoor ii |c/ TABLE OF CONTENTS t<y THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION 0? TEH-IS USED 1 The Problem 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Importance of the Study 1 Definition of Terms Used 2 Atomic Number 2 Atomic Weight 2 Element 2 Periodic Classification 2 Periodic Lav • • 3 BRIEF RtiVJiM OF THE LITERATURE 3 Books .3 Other References. .A BACKGROUND HISTORY A Purpose A Early Attempts at Classification A Early "Elements" A Attempts by Aristotle 6 Other Attempts 7 DOBEREBIER'S TRIADS AND SUBSEQUENT INVESTIGATIONS. 8 The Triad Theory of Dobereiner 10 Investigations by Others. ... .10 Dumas 10 Pettehkofer 10 Odling 11 iii TEE TELLURIC EELIX OF DE CHANCOURTOIS H Development of the Telluric Helix 11 Acceptance of the Helix 12 NEWLANDS' LAW OF THE OCTAVES 12 Newlands' Chemical Background 12 The Law of the Octaves. .........' 13 Acceptance and Significance of Newlands' Work 15 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LOTHAR MEYER ' 16 Chemical Background of Meyer 16 Lothar Meyer's Arrangement of the Elements. 17 THE WORK OF MENDELEEV AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 19 Mendeleev's Scientific Background .19 Development of the Periodic Law . .19 Significance of Mendeleev's Table 21 Atomic Weight Corrections. 21 Prediction of Hew Elements . .22 Influence -

Rediscovery of the Elements — a Historical Sketch of the Discoveries

REDISCOVERY OF THE ELEMENTS — A HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE DISCOVERIES TABLE OF CONTENTS incantations. The ancient Greeks were the first to Introduction ........................1 address the question of what these principles 1. The Ancients .....................3 might be. Water was the obvious basic 2. The Alchemists ...................9 essence, and Aristotle expanded the Greek 3. The Miners ......................14 philosophy to encompass a obscure mixture of 4. Lavoisier and Phlogiston ...........23 four elements — fire, earth, water, and air — 5. Halogens from Salts ...............30 as being responsible for the makeup of all 6. Humphry Davy and the Voltaic Pile ..35 materials of the earth. As late as 1777, scien- 7. Using Davy's Metals ..............41 tific texts embraced these four elements, even 8. Platinum and the Noble Metals ......46 though a over-whelming body of evidence 9. The Periodic Table ................52 pointed out many contradictions. It was taking 10. The Bunsen Burner Shows its Colors 57 thousands of years for mankind to evolve his 11. The Rare Earths .................61 thinking from Principles — which were 12. The Inert Gases .................68 ethereal notions describing the perceptions of 13. The Radioactive Elements .........73 this material world — to Elements — real, 14. Moseley and Atomic Numbers .....81 concrete basic stuff of this universe. 15. The Artificial Elements ...........85 The alchemists, who devoted untold Epilogue ..........................94 grueling hours to transmute metals into gold, Figs. 1-3. Mendeleev's Periodic Tables 95-97 believed that in addition to the four Aristo- Fig. 4. Brauner's 1902 Periodic Table ...98 telian elements, two principles gave rise to all Fig. 5. Periodic Table, 1925 ...........99 natural substances: mercury and sulfur. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

Feb 05 2.Indd

Pittsburgh Section http://membership.acs.org/P/Pitt Volume: LXXXX No.6 February 2005 Pittsburgh Award 2004 Pittcon 2005 The following pictures were taken at the 2004 Pittsburgh Award Dinner held on December The Pittsburgh Conference will 9, 2004 at the Sheraton Station Square Hotel. The Dinner honored 2004 Pittsburgh Award be held in Orlando, FL, February winner, Terrence J. Collins, Lord Professor of Chemistry at Carnegie Mellon University. 27 through March 4, 2005. This The Pittsburgh Award was established in 1932 by the Pittsburgh Section of the ACS to year’s theme is: Pittcon2005, recognize outstanding leadership in chemical affairs in the local and larger professional Everything Science Under the community. The award symbolizes the honor and appreciation accorded to those who have rendered distinguished service to the field of chemistry. Sun! Contents . Pittsburgh Award 2004 1 Eastern Analytical Symposium 2 Job Searching for Chemical Professionals 3 ACS Pittsburgh Chemists Club 4 “Hydrogen Storage: Prospects and Problems” SACP February Meeting 4 “Nanoparticle/Cancer Drugs” Energy Technology Group 5 Terry Collin’s Group. Seated: Terry Collins Front row: Sujit Mondal, Evan Beach, Arani “Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis: Can It Chanda, Delia Popescu, Deboshri Banerjee, Yong-Li Qian, Colin Horwitz, Paul Anastas (Pittsburgh Award Committee) Back Row: Neil Donahue (Pittsburgh Award Committee), Become a Reality for the U.S.?” Mark Beir (Pittsburgh Award Committee), Matt Stadler, Jennifer Henry, Melani Vrabel, SSP March Meeting 5 Eric Rohanna, -

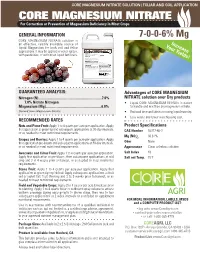

CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE SOLUTION | FOLIAR and SOIL APPLICATION CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE for Correction Or Prevention of Magnesium Deficiency in Most Crops

CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE SOLUTION | FOLIAR AND SOIL APPLICATION CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE For Correction or Prevention of Magnesium deficiency in Most Crops GENERAL INFORMATION 7-0-0-6% Mg CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE solution is an effective, readily available source of Increase liquid Magnesium for both soil and foliar your applications. It may be applied in water sprays, yields! with pesticides, or with most liquid fertilizers. GuARANTEEd ANALysIs: Advantages of CORE MAGNEsIuM Nitrogen (N).........................................................................7.0% NITRATE solution over dry products 7.0% Nitrate Nitrogen • Liquid CORE MAGNESIUM NITRATE is easier Magnesium (Mg)................................................................6.0% to handle and mix than dry magnesium nitrate. Derived from: Magnesium Nitrate. • Reduced time and labor cost using liquid over dry. • Less waste and lower warehousing cost. RECOMMENdEd RATEs Nuts and Pome Fruit: Apply 1 to 4 quarts per acre per application. Apply Product specifications first application at green tip and subsequent applications at 30-day intervals, CAs Number 10377-60-3 or as needed to meet nutritional requirements. Mg (NO3)2 36.61% Grapes and Berries: Apply 1 to 4 quarts per acre per application. Apply first application pre-bloom and subsequent applications at 30-day intervals, Odor None or as needed to meet nutritional requirements. Appearance Clear, colorless solution Avocados and Citrus Fruit: Apply 1 to 4 quarts per acre per application. salt Index 43 Apply first application at pre-bloom, then subsequent applications at mid salt out Temp. 15˚F crop and 3 to 4 weeks prior to harvest, or as needed to meet nutritional requirements. stone Fruit: Apply 1 to 4 quarts per acre per application. -

THE 19Th CENTURY GERMAN DIARY of a NEW JERSEY GEOLOGIST

THE 19th CENTURY GERMAN DIARY OF A NEW JERSEY GEOLOGIST BY WILLIAM J. CHUTE WILLIAM J. CHUTE, formerly an Instructor in History at Rutgers, is now a member of the history faculty at Queens Collegey New York. N THE FALL of 1852 a young New Jersey scientist William Kitchell, 25 years of age, embarked for Germany in the fashion I of the day to acquire the advanced training which would pre- pare him for his position as professor of geology at the Newark Wesleyan Institute. He was accompanied by a friend, William H. Bradley, and upon arrival both matriculated at the Royal Saxon Mining Academy at Freiburg near Dresden. Sporadically during the next year and a half, Kitchell jotted down his impressions of a multitude of things in a diary—now in the possession of the Rutgers University Library. While his descriptive powers were limited and his style of writing would have received no prize for polish, the diary is informative and entertaining—the personal sketches of world famous men of science, the prevalence of soldiers in Berlin, the hor- rible climate, the slowness of transportation, his questioning of the authenticity of the Genesis story of the great flood are as interesting as the comical and persistent match-making innuendoes of his land- lady and the undisguised matrimonial suggestions of her unblushing daughter. Anecdotes of his American friends who later achieved re- nown are a welcome contribution to the biographer. Kitchell's own claim to fame was won as the director of the New Jersey Geological Survey begun in 1854. -

History of Frontal Concepts Tn Meteorology

HISTORY OF FRONTAL CONCEPTS TN METEOROLOGY: THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE NORWEGIAN THEORY by Gardner Perry III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1961 Signature of'Author . ~ . ........ Department of Humangties, May 17, 1959 Certified by . v/ .-- '-- -T * ~ . ..... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Chairman0 0 e 0 o mmite0 0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Theses II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research for and the development of this thesis could not have been nearly as complete as it is without the assistance of innumerable persons; to any that I may have momentarily forgotten, my sincerest apologies. Conversations with Professors Giorgio de Santilw lana and Huston Smith provided many helpful and stimulat- ing thoughts. Professor Frederick Sanders injected thought pro- voking and clarifying comments at precisely the correct moments. This contribution has proven invaluable. The personnel of the following libraries were most cooperative with my many requests for assistance: Human- ities Library (M.I.T.), Science Library (M.I.T.), Engineer- ing Library (M.I.T.), Gordon MacKay Library (Harvard), and the Weather Bureau Library (Suitland, Md.). Also, the American Meteorological Society and Mr. David Ludlum were helpful in suggesting sources of material. In getting through the myriad of minor technical details Professor Roy Lamson and Mrs. Blender were indis-. pensable. And finally, whatever typing that I could not find time to do my wife, Mary, has willingly done. ABSTRACT The frontal concept, as developed by the Norwegian Meteorologists, is the foundation of modern synoptic mete- orology. The Norwegian theory, when presented, was rapidly accepted by the world's meteorologists, even though its several precursors had been rejected or Ignored. -

HYSTERIA at the EDINBURGH INFIRMARY: the CONSTRUCTION and TREATMENT of a DISEASE, 1770-1800 by GUENTER B

Medical History, 1988, 32: 1-22. HYSTERIA AT THE EDINBURGH INFIRMARY: THE CONSTRUCTION AND TREATMENT OF A DISEASE, 1770-1800 by GUENTER B. RISSE* I In the introduction to his History of sexuality, Michel Foucault pointed to the eighteenth century as the period in which sexuality became a medical concern and women were, in his words, subjected to "hysterization".' By this term, Foucault probably meant that medicine began to pay greater attention to female bodily functions, trying to explain anew women's behaviour and physical complaints within the prevailing theoretical frameworks of the time. Thus, Foucault's seemingly novel "medicine of hysteria" replaced traditional and popular views based on humours, vapours, and the effects of a wandering womb. In his view, this was just one aspect of the medicalization imposed on eighteenth-century life with its inherent shifts in power relationships which constitutes one of the central motifs in his writings.2 The present investigation started out as an effort to organize a rich source ofprimary clinical material: lecture notes and patient case histories from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh during the late-eighteenth century.3 The analysis focused on hospitalized patients labelled as suffering from "hysteria", trying to document and perhaps clarify Foucault's ideas on the subject. Using such historical evidence, this study made some rather unexpected discoveries. It not only exposed the ambiguities inherent in the construction of disease entities, but also refuted Foucault's account of the sexualization ofworking-class women, at least for late-eighteenth-century Edinburgh. Before presenting the archival data, however, it will be useful briefly to consider the views regarding women's health and especially hysteria prevalent in the medical literature during the latter part of the eighteenth century. -

5. the Lives of Two Pioneering Medical Chemists.Indd

The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings The Lives of Two Pioneering Medical-Chemists in Bristol Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808) and William Herapath (1796-1868) Brian Vincent School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TS. Presented at the meeting on Dec 12th 2016 ABSTRACT From the second half of the 18th century onwards the new science of chemistry took root and applications were heralded in many medical-related fields, e.g. cures for diseases such as TB, the prevention of epidemics like cholera, the application of anaesthetics and the detection of poisons in forensics. Two pioneering chemists who worked in the city were Thomas Beddoes, who founded the Pneumatic Institution in Hotwells in 1793, and William Herapath who was the first professor of chemistry and toxicology at the Bristol Medical School, located near the Infirmary, which opened in 1828. As well as their major contributions to medical-chemistry, both men played important roles in the political life of the city. INTRODUCTION The second half of the 18th century saw chemistry emerge as a fledgling science. Up till then there was little understanding of the true nature of matter. The 1 The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings classical Greek idea that matter consisted of four basic elements (earth, fire, water and air) still held sway, as did the practice of alchemy: the search for the “elixir of life” and for the “philosophers’ stone” which would turn base metals into gold. -

Public Cultii En

Ursula Klein MPIWG Berlin [email protected] The Public Cult of Natural History and Chemistry in the age of Romanticism In einem Zeitalter wo man alles Nützliche mit so viel Enthusiasmus auffasst… (I. v. Born und F. W. H. v. Trebra)1 The chemical nature of the novel, criticism, wit, sociability, the newest rhetoric and history thus far is self-evident (F. Schlegel)2 Chemistry is of the most widespread application and of the most boundless influence on life (Goethe)3 In May 1800 the philosopher and theologian Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher wrote his sister Charlotte that at the time he was attending in Berlin “lectures about all kinds of sciences, … among others about chemistry.”4 The “chemistry” to which he was referring were the regular public lectures given by the Berlin chemist and apothecary Martin Heinrich Klaproth starting in 1783. The theologian-philosopher’s interest in chemistry was by no means superficial, as his lecture notes document.5 What was it about chemistry of that time that fascinated Schleiermacher? Goethe’s Elective Affinity (“Wahlverwandtschaft”) immediately comes to mind, in which a tragic conflict between marital bonds and love is portrayed in the light of chemical affinities or “elective affinities,” as do Johann Wilhelm Ritter’s spectacular electrochemical experiments and speculations on natural philosophy. Yet a look at Schleiermacher’s notes on Klaproth’s lectures from the year 1800 immediately informs us that this would be mistaken. Very little mention of chemical theories can be found in Klaproth’s lectures, let alone of speculative natural philosophy. In his lectures Klaproth betook himself instead to the multi-faceted world of material substances.