Nitrogen, and the Demise of Phlogiston III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HYSTERIA at the EDINBURGH INFIRMARY: the CONSTRUCTION and TREATMENT of a DISEASE, 1770-1800 by GUENTER B

Medical History, 1988, 32: 1-22. HYSTERIA AT THE EDINBURGH INFIRMARY: THE CONSTRUCTION AND TREATMENT OF A DISEASE, 1770-1800 by GUENTER B. RISSE* I In the introduction to his History of sexuality, Michel Foucault pointed to the eighteenth century as the period in which sexuality became a medical concern and women were, in his words, subjected to "hysterization".' By this term, Foucault probably meant that medicine began to pay greater attention to female bodily functions, trying to explain anew women's behaviour and physical complaints within the prevailing theoretical frameworks of the time. Thus, Foucault's seemingly novel "medicine of hysteria" replaced traditional and popular views based on humours, vapours, and the effects of a wandering womb. In his view, this was just one aspect of the medicalization imposed on eighteenth-century life with its inherent shifts in power relationships which constitutes one of the central motifs in his writings.2 The present investigation started out as an effort to organize a rich source ofprimary clinical material: lecture notes and patient case histories from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh during the late-eighteenth century.3 The analysis focused on hospitalized patients labelled as suffering from "hysteria", trying to document and perhaps clarify Foucault's ideas on the subject. Using such historical evidence, this study made some rather unexpected discoveries. It not only exposed the ambiguities inherent in the construction of disease entities, but also refuted Foucault's account of the sexualization ofworking-class women, at least for late-eighteenth-century Edinburgh. Before presenting the archival data, however, it will be useful briefly to consider the views regarding women's health and especially hysteria prevalent in the medical literature during the latter part of the eighteenth century. -

5. the Lives of Two Pioneering Medical Chemists.Indd

The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings The Lives of Two Pioneering Medical-Chemists in Bristol Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808) and William Herapath (1796-1868) Brian Vincent School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TS. Presented at the meeting on Dec 12th 2016 ABSTRACT From the second half of the 18th century onwards the new science of chemistry took root and applications were heralded in many medical-related fields, e.g. cures for diseases such as TB, the prevention of epidemics like cholera, the application of anaesthetics and the detection of poisons in forensics. Two pioneering chemists who worked in the city were Thomas Beddoes, who founded the Pneumatic Institution in Hotwells in 1793, and William Herapath who was the first professor of chemistry and toxicology at the Bristol Medical School, located near the Infirmary, which opened in 1828. As well as their major contributions to medical-chemistry, both men played important roles in the political life of the city. INTRODUCTION The second half of the 18th century saw chemistry emerge as a fledgling science. Up till then there was little understanding of the true nature of matter. The 1 The West of England Medical Journal Vol 116 No 4 Article 2 Bristol Medico-Historical Society Proceedings classical Greek idea that matter consisted of four basic elements (earth, fire, water and air) still held sway, as did the practice of alchemy: the search for the “elixir of life” and for the “philosophers’ stone” which would turn base metals into gold. -

Bibliography of Secondary Sources

BibliographyBibliography of Secondary of Secondary Sources Sources 355 Bibliography of Secondary Sources Albury, William, “The Order of Ideas: Condillac’s method of analysis as a political instru- ment in the French Revolution,” John Schuster and R.R. Yeo, eds., The Politics and Rhetoric of Scientific Method: Historical studies (Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Co., 1986), 203-225. Alder, Ken, “A Revolution to Measure: The political economy of the metric system in France,” M. Norton Wise, ed., Values of Precision (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 39-71. Alder, Ken, Engineering the Revolution: Arms and enlightenment in France, 1763-1815 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999). Alder, Ken, “Innovation and Amnesia: Engineering rationality and the fate of inter- changeable parts manufacturing in France,” Technology and Culture 38 (1997): 273-311. Algazi, Gadi, “Scholars in Households: Refiguring the learned habitus, 1480-1550,” Science in Context 16 (2003): 9-42. Allchin, Douglas, “James Hutton and Coal,” Cadernos IG/UNICAMP 7 (1997): 167-183. Allen, Tim, Mike Cotterill, Geoffrey Pike, “The Kentish Copperas Industry,” Archeologia Cantiana, 122 (2002), 319-334. Amin, Wahida, “The Poetry and Science of Humphry Davy,” PhD Thesis, University of Salford, 2013. Anderson, R.G.W., “A Source for Eighteenth Century Chemical Glass,” Georgi Dragoni, Anita McConnell and Gerard L’E. Turner, eds., Proceedings of the Eleventh International Scientific Commission Symposium (Bologna: Grafis Edizioni, 1994): 47-52. Anderson, R.G.W., “Chemistry Beyond the Academy: Diversity in Scotland in the early nineteenth century,” Ambix 57 (2010): 84-103. Anderson, R.G.W., The Playfair Collection and the Teaching of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh, 1713-1858 (Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Museum, 1978). -

Section 1 – Oxygen: the Gas That Changed Everything

MYSTERY OF MATTER: SEARCH FOR THE ELEMENTS 1. Oxygen: The Gas that Changed Everything CHAPTER 1: What is the World Made Of? Alignment with the NRC’s National Science Education Standards B: Physical Science Structure and Properties of Matter: An element is composed of a single type of atom. G: History and Nature of Science Nature of Scientific Knowledge Because all scientific ideas depend on experimental and observational confirmation, all scientific knowledge is, in principle, subject to change as new evidence becomes available. … In situations where information is still fragmentary, it is normal for scientific ideas to be incomplete, but this is also where the opportunity for making advances may be greatest. Alignment with the Next Generation Science Standards Science and Engineering Practices 1. Asking Questions and Defining Problems Ask questions that arise from examining models or a theory, to clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships. Re-enactment: In a dank alchemist's laboratory, a white-bearded man works amidst a clutter of Notes from the Field: vessels, bellows and furnaces. I used this section of the program to introduce my students to the concept of atoms. It’s a NARR: One night in 1669, a German alchemist named Hennig Brandt was searching, as he did more concrete way to get into the atomic every night, for a way to make gold. theory. Brandt lifts a flask of yellow liquid and inspects it. Notes from the Field: Humor is a great way to engage my students. NARR: For some time, Brandt had focused his research on urine. He was certain the Even though they might find a scientist "golden stream" held the key. -

Edinburgh Walking Tour , Eh2 3Ns Chambers Street, Eh1 1Jf 52 Queen Street

EDINBURGH WALKING TOUR CHLOROFORM CARBON DIOXIDE 52 QUEEN STREET, EH2 3NS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCOTLAND, National Portrait Gallery Chloroform is an organic compound with formula CHCl . Today several million CHAMBERS STREET, EH1 1JF 3 St Andrew’s tonnes are produced annually as a precursor to PTFE (polytetrafluoroethlyene) Bus Station Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a naturally occurring compound and is the primary CHE and refrigerants, although its use for refrigerants is being phased out. MISTRY source of carbon for life on Earth. It exists in the Earth’s atmosphere as a trace It was in this very house, on the 4th of November, 1847, that James Young gas at a concentration of 0.039 % by volume, but this concentration is rapidly Queen Street Royal College A900 Simpson and friends first inhaled chloroform after dinner, sending them increasing with the burning of carbon-based fuels such as coal, oil and gas. An of Physicians TRAIL South St Andrew Street unconscious until the following morning! Within days James Young Simpson increased level of CO2 in the atmosphere is contributing to the rate of global who was an obstetrician, was administering it to his patients during childbirth. warming and ocean acidification. St Andrew South St David StreetSquare The use of chloroform during surgery expanded across Europe and in the Joseph Black, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh (1766 to George Street Leith Street 1850s chloroform was used at the birth of Queen Victoria’s last two children. 1796) discovered carbon dioxide gas in 1756. Black observed that the gas, At the beginning of the 20th century its use was abandoned due to the which he called ‘fixed air,’ was denser than air and supported neither flame nor Waterloo Place National P discovery of chloroform’s toxicity, especially its tendency to cause fatal A1 ortrait animal life. -

Relations Between Industry and Academe in Scotland, and the Case of Dyeing: 1760 to 1840

Relations between Industry and Academe in Scotland 333 Chapter 14 Relations between Industry and Academe in Scotland, and the Case of Dyeing: 1760 to 1840 Robert G.W. Anderson What was the role of academic chemists in relation to those who were directly involved in developing Scotland’s burgeoning chemical industry between 1760 and 1840? Traditionally, most historians have suggested that there was little involvement between academics and manufacturers across Europe. More recently, some historians suggest that it is difficult to disentangle their rela- tions; it is best, they argue, to speak of hybrid identities. Neither extreme is sustainable when Scottish evidence is examined; an intermediate position, depending on the particular individual concerned, paints a more plausible pic- ture. Some academics interacted closely with enterprising manufacturers, others less so. This essay provides a general introduction to the issues, followed by an analysis of the case of the pre-synthetic dyestuffs industry. The traditional view holds that the academic world of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not play a role. In a paper of 1797, Theophilus Lewis Rupp (d.1805), a German-born Manchester cotton manufacturer wrote, The arts, which supply the luxuries, conveniences, and necessaries of life, have derived but little advantage from philosophers […] The chemist, in particular, if we except the pharmaceutical laboratory, has but little claim on the arts: on the contrary, he is indebted to them for the greatest discov- eries and a prodigious number of facts, which form the basis of his science […] [N]o brand of the useful arts is less indebted to him than that of changing the colours of substances. -

Founding Fellows

Founding Members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Alexander Abercromby, Lord Abercromby William Alexander John Amyatt James Anderson John Anderson Thomas Anderson Archibald Arthur William Macleod Bannatyne, formerly Macleod, Lord Bannatyne William Barron (or Baron) James Beattie Giovanni Battista Beccaria Benjamin Bell of Hunthill Joseph Black Hugh Blair James Hunter Blair (until 1777, Hunter), Robert Blair, Lord Avontoun Gilbert Blane of Blanefield Auguste Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy Ebenezer Brownrigg John Bruce of Grangehill and Falkland Robert Bruce of Kennet, Lord Kennet Patrick Brydone James Byres of Tonley George Campbell John Fletcher- Campbell (until 1779 Fletcher) John Campbell of Stonefield, Lord Stonefield Ilay Campbell, Lord Succoth Petrus Camper Giovanni Battista Carburi Alexander Carlyle John Chalmers William Chalmers John Clerk of Eldin John Clerk of Pennycuik John Cook of Newburn Patrick Copland William Craig, Lord Craig Lorentz Florenz Frederick Von Crell Andrew Crosbie of Holm Henry Cullen William Cullen Robert Cullen, Lord Cullen Alexander Cumming Patrick Cumming (Cumin) John Dalrymple of Cousland and Cranstoun, or Dalrymple Hamilton MacGill Andrew Dalzel (Dalziel) John Davidson of Stewartfield and Haltree Alexander Dick of Prestonfield Alexander Donaldson James Dunbar Andrew Duncan Robert Dundas of Arniston Robert Dundas, Lord Arniston Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville James Edgar James Edmonstone of Newton David Erskine Adam Ferguson James Ferguson of Pitfour Adam Fergusson of Kilkerran George Fergusson, Lord Hermand -

The Glasgow School in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century 219

CHAPTERXIV THE GLASGOWSCHOOLIN THE FIRST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ONE of the most important steps in connection with the clevelopment of the Glasgow Medical School was the foundation of a hospital where clinical teaching could take place. Glasgow, in 1712, was a small burgh with a population of 14,000, CLASGOW ROYAL INFIRMARY IN 1861 The original Adams building (medical house) is to tlie front; the fever-house. (later surgical) to tlie right : and the newly-erected surgical block to tlie rear. Lister's Wards are those on either side of the door in tlie rear building: tlie male ward on the ground floor, to the left, and the female ward on the first floor up. to the right but during the 18th century, in consequence of the development of trade with the ~merican'colonies, the population rose rapidly, and in 1801 had reached 83,000, while thirty years later h still more rapid rise brought the number of inhabitants 218 HISTORY OF SCOTTISH MEDICINE -- -- -- - - - ------ ---.- of the city and its suburbs to about 200,000 in the year 1831. Situated in the Old Green, the Town's Hospital, which corresponded very much to a modern workhouse, subserved the needs of the city in the early part of the 18th century. A movement, begun in 1787, to provide a general hospital, which was an indis- pensable adjunct to a medical school, took shape, so that in December, 1794, the Royal Infirmary was formally opened for the reception of patients. The sitc of this hospital was that of the old Archbishop's Castle, adjoining the Cathedral and close to the University buildings in the High Street, and, as originally built, its capacity was for 150 patients.l The Western Infirmary was not inaugurated until 1874, when another hospital became necessary, partly because of the increase of the population in the city and partly because of the migration of the University to Gilmorehill in the western part of Glasgow. -

Travellers in Ottoman Lands Previous Volumes Published from ASTENE Conferences

Travellers in Ottoman Lands Previous volumes published from ASTENE Conferences: Desert Travellers from Herodotus to T E Lawrence (2000), edited by Janet Starkey and Okasha El Daly. Durham, ASTENE. Travellers in the Levant: Voyagers and Visionaries (2001), edited by Sarah Searight and Malcolm Wagstaff. Durham, ASTENE. Egypt Through the Eyes of Travellers (2002), edited by Paul Starkey and Nadia El Kholy. Durham, ASTENE. Travellers in the Near East (2004), edited by Charles Foster. London, Stacey International. Women Travellers in the Near East (2005), edited by Sarah Searight. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Who Travels Sees More: Artists, Architects and Archaeologists Discover Egypt and the Near East (2007), edited by Diane Fortenberry. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Saddling the Dogs: Journeys through Egypt and the Near East (2009), edited by Diane Fortenberry and Deborah Manley. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Knowledge is Light: Travellers in the Near East (2011), edited by Katherine Salahi. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Souvenirs and New Ideas: Travel and Collecting in Egypt and the Near East, edited by Diane Fortenberry. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Every Traveller Needs a Compass, edited by Neil Cooke and Vanessa Daubney. Oxford, ASTENE and Oxbow Books. Lost and Now Found,: Explorers, Diplomats and Artists in Egypt and the Near East, edited by Neil Cooke and Vanessa Daubne. Oxford, ASTENE and Archaeopress Publishing. TRAVELLERS IN OTTOMAN LANDS The Botanical Legacy Edited by Ines Aščerić-Todd, Sabina Knees, Janet Starkey and Paul Starkey ASTENE and Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, Oxford Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 915 3 ISBN 978 1 78491 916 0 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2018 Cover images: Background Çiçeklerin dâhisi (The genius of flowers) by illustrator-artist Sema Yekeler Yurtseven. -

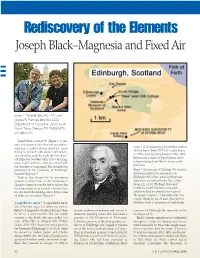

Joseph Black–Magnesia and Fixed Air III

Rediscovery of the Elements Joseph Black–Magnesia and Fixed Air III James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, Department of Chemistry, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, [email protected] Joseph Black (1728–1799) (Figure 1) is per- haps best known for the discovery and charac- terization of carbon dioxide (fixed air), made Figure 1. (Left) Engraving of Joseph Black, made in during his research with alkalies and carbon- 1800 by James Heath (1757–1834), taken from a ates. Simultaneously, he made the first chemi- ca 1790 portrait by Henry Raeburn (1756–1823). cal distinction between calcia (CaO) and mag- Raeburn was a student of David Martin, whose nesia (MgO) and thus could be credited with portrait of young Joseph Black is shown on the the discovery of magnesium. This research was front cover. performed at the University of Edinburgh, Figure 2. Modern map of Edinburgh. The chemical Scotland (Figure 2).1b discoveries of Black were performed at the Black is also known for his pioneering Edinburgh “Old College,” whose buildings were research in latent heat at the University of taken down and replaced by the “New College” Glasgow, where he was the first to notice that during 1827–1831. The Royal Museum of the temperature of an ice-water mixture does Scotland is located 200 meters west, where not rise above the freezing point of water until exhibits on Black are presented (see Figure 8). all of the ice has melted (Figure 3).1d The modern campus is 2.7 km south of the “New College.” During his last 18 years, Black lived on Joseph Black’s career.1b,d,2 Joseph Black’s family Nicholson Street, a continuation of South Bridge. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Self-Guided Tour of the King's Buildings Campus

24 42 To the Royal Observatory 67 Mayfield Road 38 GATE 1 41 To the GATE 2 24 38 West Mains Road University 42 41 38 Central Area 67 Max Born Crescent Born Max James Dewar Road West Mains Road Esslemont Road 38 DP P James Hutton Road To Edinburgh BioQuarter DP DP C 41 DP 4 2 GATE 3 8 DP 1* Max Born Crescent DP * Road Brown Crum Alexander P Hallhead Road P N 3 67 P KB Robert Stevenson Road Square P Mayfield Road DP P Colin Maclaurin Road 67 Nucleus C P 5 development 16 C P Ross Road 9 GATE 4 Marion Ross Road P DP DP Thomas Bayes Road DP 15 P P11 Self-guided tour Max Born Crescent P DP 7 P 6 Max Born Crescent King’s Buildings campus DP C DP 13 14 DP Road Tait Peter Guthrie 10 and surrounding area Nicholas Kemmer Road DP New biology P development C 12 A warm welcome to the University of Edinburgh and the city of Edinburgh. ONE-WAY EXIT This tour is for King’s Buildings, the University’s second largest campus. Subjects within the College of Science and Engineering are taught here. DP The student union is also open for all students at the University. This tour takes you in a circle, so whichever number you start at will allow Max Born Crescent you to complete the full tour. The recommended starting points are from the main entrance outside Ashworth Laboratories (Starting Point 1), near Mayfield Road where buses 24, 42 and 67 stop, or from the King’s King’s Buildings campus map key 1 Starting Point 1 - Ashworth Laboratories Buildings bus stop (Starting Point 2), where the number 41 bus drops off.