D2.5 FAIR Semantics Recommendations Second Iteration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISO/TC46 (Information and Documentation) Liaison to IFLA

ISO/TC46 (Information and Documentation) liaison to IFLA Annual Report 2015 TC46 on Information and documentation has been leading efforts related to information management since 1947. Standards1 developed under ISO/TC46 facilitate access to knowledge and information and standardize automated tools, computer systems, and services relating to its major stakeholders of: libraries, publishing, documentation and information centres, archives, records management, museums, indexing and abstracting services, and information technology suppliers to these communities. TC46 has a unique role among ISO information-related committees in that it focuses on the whole lifecycle of information from its creation and identification, through delivery, management, measurement, and archiving, to final disposition. *** The following report summarizes activities of TC46, SC4, SC8 SC92 and their resolutions of the annual meetings3, in light of the key-concepts of interest to the IFLA community4. 1. SC4 Technical interoperability 1.1 Activities Standardization of protocols, schemas, etc. and related models and metadata for processes used by information organizations and content providers, including libraries, archives, museums, publishers, and other content producers. 1.2 Active Working Group WG 11 – RFID in libraries WG 12 – WARC WG 13 – Cultural heritage information interchange WG 14 – Interlibrary Loan Transactions 1.3 Joint working groups 1 For the complete list of published standards, cfr. Appendix A. 2 ISO TC46 Subcommittees: TC46/SC4 Technical interoperability; TC46/SC8 Quality - Statistics and performance evaluation; TC46/SC9 Identification and description; TC46/SC 10 Requirements for document storage and conditions for preservation - Cfr Appendix B. 3 The 42nd ISO TC46 plenary, subcommittee and working groups meetings, Beijing, June 1-5 2015. -

Internet, Interoperability and Standards – Filling the Gaps

Internet, Interoperability and Standards – Filling the Gaps Janifer Gatenby European Product Manager Geac Computers [email protected] Abstract: With major changes in electronic communications, the main focus of standardisation in the library arena has moved from that of supporting efficiency to allowing library users to access external resources and allowing remote access to library resources. There is a new emphasis on interoperability at a deeper level among library systems and on a grander scale within the environment of electronic commerce. The potential of full inter-operability is examined along with its likely impact. Some of the gaps in current standards are examined, with a focus on information retrieval, together with the process for filling those gaps, the interoperation of standards and overlapping standards. Introduction Libraries now find themselves in a very new environment. Even though they have always co-operated with one another and have led standards efforts for decades, their inter- operability has been at arm's length via such means as store and forward interlibrary loans and electronic orders. The initial goals of standardisation were to increase efficiency, e.g. by exchanging cataloguing, by electronic ordering and only secondarily to share resources. Initial standards efforts in libraries concentrated on record exchange as part of the drive to improve efficiency by sharing cataloguing. This led to a raft of bibliographic standards concentrating on: the way in which catalogue records are made (contents - cataloguing rules such as AACR2, classification schemes, subject headings, name headings) how they are identified (LC card number, ISBN, ISSN etc.) how they are structured for exchange (MARC) Viewing library standardisation chronologically, acquisitions was the next area where libraries strove to increase efficiency co-operatively. -

A Könyvtárüggyel Kapcsolatos Nemzetközi Szabványok

A könyvtárüggyel kapcsolatos nemzetközi szabványok 1. Állomány-nyilvántartás ISO 20775:2009 Information and documentation. Schema for holdings information 2. Bibliográfiai feldolgozás és adatcsere, transzliteráció ISO 10754:1996 Information and documentation. Extension of the Cyrillic alphabet coded character set for non-Slavic languages for bibliographic information interchange ISO 11940:1998 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Thai ISO 11940-2:2007 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Thai characters into Latin characters. Part 2: Simplified transcription of Thai language ISO 15919:2001 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Devanagari and related Indic scripts into Latin characters ISO 15924:2004 Information and documentation. Codes for the representation of names of scripts ISO 21127:2014 Information and documentation. A reference ontology for the interchange of cultural heritage information ISO 233:1984 Documentation. Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters ISO 233-2:1993 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters. Part 2: Arabic language. Simplified transliteration ISO 233-3:1999 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Arabic characters into Latin characters. Part 3: Persian language. Simplified transliteration ISO 25577:2013 Information and documentation. MarcXchange ISO 259:1984 Documentation. Transliteration of Hebrew characters into Latin characters ISO 259-2:1994 Information and documentation. Transliteration of Hebrew characters into Latin characters. Part 2. Simplified transliteration ISO 3602:1989 Documentation. Romanization of Japanese (kana script) ISO 5963:1985 Documentation. Methods for examining documents, determining their subjects, and selecting indexing terms ISO 639-2:1998 Codes for the representation of names of languages. Part 2. Alpha-3 code ISO 6630:1986 Documentation. Bibliographic control characters ISO 7098:1991 Information and documentation. -

Semantic Representation of Provenance and Contextual Information in Scientific Research

Semantic Representation of Provenance and Contextual Information in Scientific Research D I S S E R T A T I O N zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Im Fach Bibliotheks- und Informationswissenschaft eingereicht an der Philosophische Fakultät I Institut für Bibliotheks- und Informationswissenschaft Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Dipl. M.Sc. Armand Brahaj Die Präsidentin der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Dr. Sabine Kunst Die Dekanin der Philosophischen Fakultät I Prof. Dr. Gabriele Metzler Gutachter/in: 1. Prof. Dr. Peter Schirmbacher 2. Prof. Dr. Vivien Petras 3. Prof. Dr. Detlev Doherr Datum der Einreichung: 16.06.2016 Datum der Promotion: 19.09.2016 i This document was created on: 14.11.2016 ii Abstract Computational and information technology is one of the biggest advancement of the last century, a revolution that is influencing the way we approach social and technical problems in our day to day life. While these technologies have already influenced the research activity per sé, it is to be expected that these innovations will significantly influence the publishing and sharing of scientific results as well. So far, scientific publications have relied on limited result data attached inline in research paper publications. Establishments supporting research are pushing for concrete solutions that allow dissemination, share and reuse of research results. Reports such as “Riding the Wave - How Europe can gain from the rising tide of scientific data” of the High Level Expert Group on Scientific Data, European Commission (High Level Expert Group on Scientific Data, October 2010) presents a vision where the challenges of diverse data formats, people and communities are avoided due to the application of technical, semantic and social features of interoperability. -

Isqv27no1.Pdf

INFORMATION STANDARDS QUARTERLY SPRING 2015 | VOL 27 | ISSUE 1 | ISSN 1041-0031 TOPIC YEAR IN REVIEW AND STATE OF THE STANDARDS NISO 2014 YEAR IN REVIEW TC46 2014 YEAR IN REVIEW THE FUTURE OF LIBRARY RESOURCE DISCOVERY STATE OF THE STANDARDS NEW for 2015: NISO Training Thursdays A technical webinar for those wanting more in-depth knowledge. Free with registration to the related Virtual Conference or register separately. UPCOMING 2015 EDUCATIONAL EVENTS APRIL JUNE OCTOBER 8 Experimenting with BIBFRAME: 10 Taking Your Website Wherever 1 Using Alerting Systems to Reports from Early Adopters You Go: Delivering Great User Ensure OA Policy Compliance (Webinar) Experience to Multiple Devices (Training Thursday) 29 Expanding the Assessment (Webinar) 14 Cloud and Web Services for Toolbox: Blending the Old 17 The Eternal To-Do List: Making Libraries (Webinar) and New Assessment Practices E-books Work in Libraries 28 Interacting with Content: (Virtual Conference) (Virtual Conference) Improving the User Experience 26 NISO/BISG The Changing (Virtual Conference) MAY Standards Landscape (In-person Forum) 7 Implementing SUSHI/ NOVEMBER COUNTER at Your Institution JULY 18 Text Mining: Digging Deep for (Training Thursday) Knowledge (Webinar) 13 Software Preservation and Use: No events in July I Saved the Files But Can I Run DECEMBER Them? (Webinar) AUGUST 2 The Semantic Web: What’s New 20 Not Business as Usual: 12 MOOCs and Libraries: and Cool (Virtual Conference) Special Cases in RDA Serials A Brewing Collaboration NISO December Two-Part Webinar: Cataloging (NISO/NASIG (Webinar) Joint Webinar) Emerging Resource Types SEPTEMBER 9 Part 1: Emerging Resource Types NISO September Two-Part Webinar: 16 Part 2: Emerging The Practicality of Managing “E” NISO Open Teleconferences Resource Types 9 Part 1: Licensing Join us each month for NISO’s Open 16 Part 2: Staffing Teleconferences—an ongoing series of calls held on the second Monday 23 Scholarly Communication of each month as a way to keep Models: Evolution the community informed of NISO’s or Revolution? activities. -

Conselleria De Sanitat Universal I Salut Pública Conselleria De Sanidad Universal Y Salud Pública

Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública Conselleria de Sanidad Universal y Salud Pública RESOLUCIÓ de 25 de mar\ de 2020, de la Consellera de RESOLUCIÓN de la consellera de Sanidad Universal y Sanitat universal i Salut Pública, en relació amb l’ordre Salud Pública, en relación con la Orden SND/271/2020, SND/271/2020, de 19 de març, del Ministeri de Sanitat, de 19 de marzo, del Ministerio de Sanidad, por la que se per la qual s’estableix l’autoritat competent per a la sol· establece la autoridad competente para la solicitud de los licitud dels EPI’s per les entitats locals, en l’àmbit de la EPI’s por las entidades locales, en el ámbito de la Comu· Comunitat Valenciana, en la situació de crisi sanitària nitat Valenciana, en la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasio· ocasionada pel COVID·19. [2020/2725] nada por el COVID·19. [2020/2725] ANTECEDENTS DE FET ANTECEDENTES DE HECHO Amb data 11 de març de 2020, l’Organització Mundial de la Salut Con fecha 11 de marzo de 2020, la Organización Mundial de la (OMS) ha declarat el brot de SARS-CoV 2, o COVID-19, com a pan- Salud (OMS) ha declarado el brote de SARS-CoV 2, o COVID-19, dèmia, elevant a aquesta extrema categoria la situació actual des de la como pandemia, elevando a dicha extrema categoría la situación actual prèvia declaració d’Emergència de Salut Pública d’Importància Inter- desde la previa declaración de Emergencia de Salud Pública de Impor- nacional. tancia Internacional. El Reial Decret 463/2020, de 14 de març, declara a nivell nacional El Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, -

2021-07-07 Report Date : Cost Centre(S)

Report Date : 2021-09-17 Cost Centre(s) : % LIST OF PUBLISHED STANDARDS Page No : 1 Of 5 Total Count: 67 Committee SANS Date Latest Reaffirmation Review/ Number Number Int Ed Ed Sansified Title Approved Amendment due Revision SABS/TC 046 SANS 438:2005/ISO 999:1996 2 1 Y Information and documentation - Guidelines 2005-10-28 2015-08-27 for the content, organization and presentation of indexes SANS 480:2006/ISO 11108:1996 1 1 Y Information and documentation - Archival 2006-03-24 2025-07-17 paper - Requirements for permanence and durability SANS 531:2007/ISO 4:1997 3 1 Y Information and documentation - Rules for the 2007-05-25 2017-03-16 abbreviation of title words and titles of publications SANS 618:2009/ISO 10324:1997 1 1 Y Information and documentation - Holdings 2009-03-13 2014-03-13 statements - Summary level SANS 690:2007/ISO 690:1987 2 1 Y Documentation - Bibliographic references - 2007-05-25 2012-05-25 Content, form and structure SANS 690-2:2007/ISO 690-2:1997 1 1 Y Information and documentation - Bibliographic 2007-05-25 2012-05-25 references Part 2: Electronic documents or parts thereof SANS 832:2007/ISO 832:1994 2 1 Y Information and documentation - Bibliographic 2007-05-25 2018-01-25 description and references - Rules for the abbreviation of bibliographic terms SANS 1105-1:2010/ISO 10161-1:1997 2 1 Y Information and documentation - Open 2010-10-01 2 I A 2010-10-01 2015-10-01 Systems Interconnection - Interlibrary loan application protocol specification Part 1: Protocol specification SANS 1105-2:2011/ISO 10161-2:1997 1 1 Y Information -

Standards Available in Electronic Format (PDF) Page 1

Standards available in electronic format (PDF) October 2019 SANS Number Edition Title SANS 1-2:2013 2 Standard for standards Part 2: Recognition of Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) in South Africa SATS 2:2012 1 The development of normative documents other than South African National Standards SANS 2:2013 7.01 Lead-acid starter batteries (SABS 2) SANS 4:2008 3.03 Locks, latches, and associated furniture for doors (SABS 4) (Domestic Type) SANS 11:2007 1.02 Unplasticized poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC-U) (SABS 11) components for external rainwater systems SANS 13:2008 2.03 Wax polish, solvent-based, for floors and furniture (SABS 13) SANS 14:1994/ISO 49:1994, IDT, Ed. 2 1 Malleable cast iron fittings threaded to ISO 7-1 (SABS ISO 49) SANS 15:2008 2.03 Wax emulsion polish for floors and furniture (SABS 15) SANS 16:2007/ISO/IEC 10116:2006, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Modes of operation for an n-bit block cipher SANS 17:2014 1.01 Glass and plastics in furniture SANS 18-1:2003/ISO/IEC 10118-1:2000, IDT, Ed. 2 1 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 1: General SANS 18-2:2011/ISO/IEC 10118-2:2010, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 2: Hash-functions using an n-bit block cipher SANS 18-3:2007/ISO/IEC 10118-3:2004, IDT, Ed. 3 2 Information technology - Security techniques - Hash- functions Part 3: Dedicated hash-functions SANS 18-4:2003/ISO/IEC 10118-4:1998, IDT, Ed. -

Standardiseringsprosjekter Og Nye Standarder

Annonseringsdato: 2010-05-28 Listenummer: 09/2010 Standardiseringsprosjekter og nye standarder Listenummer: 09/2010 Side: 1 av 153 01 Generelt. Terminologi. Standardisering. Dokumentasjon 01 Generelt. Terminologi. Standardisering. Dokumentasjon Standardforslag til høring - europeiske (CEN) prEN 1089-3 Transportable gassflasker - Kjennetegn (unntatt LPG) - Del 3: Fargekoding Transportable gas cylinders - Gas cylinder identification (excluding LPG) - Part 3: Colour coding Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 04.08.2010 prEN 1089-3 Transportable gassflasker - Kjennetegn (unntatt LPG) - Del 3: Fargekoding Transportable gas cylinders - Gas cylinder identification (excluding LPG) - Part 3: Colour coding Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 04.08.2010 prEN 1540 Arbeidsplassluft - Terminologi Workplace exposure - Terminology Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 22.09.2010 prEN 15898 Kulturminner - Generelle hovedtermer og definisjoner for kulturminner Conservation of cultural property - Main general terms and definitions concerning conservation of cultural property Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 29.06.2010 prEN 15898 Conservation of cultural property - Main general terms and definitions concerning conservation of cultural property Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 29.06.2010 prEN ISO 9092 Tekstiler - Ikke-vevd materiale (florstoff) - Definisjon (ISO/DIS 9092:2010) Textiles - Nonwoven - Definition (ISO/DIS 9092:2010) Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 04.08.2010 prEN ISO 10209 Technical product documentation - Vocabulary - Terms relating to technical drawings, product definition and related products (ISO/DIS 10209:2010) Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 25.08.2010 Standardforslag til høring - internasjonale (ISO) ISO 7010:2003/DAmd 71 Safety sign P025: Do not use this incomplete scaffold Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 30.05.2010 ISO 7010:2003/DAmd 72 Safety sign P026: Do not use this device in a bathtub, shower or water-filled reservoir Språk: en Kommentarfrist: 30.05.2010 Listenummer: 09/2010 Side: 2 av 153 01 Generelt. -

International Standard Iso/Iec 11179-7:2019(E)

This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80019088 INTERNATIONAL ISO/IEC STANDARD 11179-7 First edition 2019-12 Information technology — Metadata registries (MDR) — Part 7: Metamodel for data set registration Reference number ISO/IEC 11179-7:2019(E) © ISO/IEC 2019 This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80019088 ISO/IEC 11179-7:2019(E) COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO/IEC 2019 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address belowCP 401or ISO’s • Ch. member de Blandonnet body in 8 the country of the requester. ISO copyright office Phone: +41 22 749 01 11 CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva Fax:Website: +41 22www.iso.org 749 09 47 PublishedEmail: [email protected] Switzerland ii © ISO/IEC 2019 – All rights reserved This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80019088 ISO/IEC 11179-7:2019(E) Contents Page Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................v -

Könyvtári Figyelő

ÚJ ISOSZABVÁNYOK A KÖNYVTÁRTUDOMÁNYI SZAKKÖNYVTÁRBAN A genfi székhelyű Nemzetközi Szabványügyi Szervezet (International Organization for Standardization, ISO) 1947-es megalakulása óta több mint száz nemzet szabványosítási tagszervezetét foglalja magában, és számos nemzetközi szabványt gondoz. A könyvtárak közötti nemzetközi együttműködés sem jöhetne létre közös irányelvek, egymásnak megfeleltethető terminusok, definíciók, dokumentum- és adatkezelési szabványok nélkül. AZ ISO szorosan együttműködik a Nemzetközi Elektrotechnikai Bizottsággal (International Electrotechnical Commission, IEC) az elektrotechnikai szabványügyi kérdésben. Az idei évben a Könyvtártudományi Szakkönyvtár állománya az alábbi könyvtárüggyel kapcsolatos nemzetközi szabvá- nyokkal gyarapodott. Az új szabványok beszerzése az Országos Könyvtári Szabványosítási Bizottsággal (OKSZB) egyez- tetve, a Bizottság javaslatainak figyelembe vételével történt. Az OKSZB-ről bővebben itt olvasható: http://www.oszk.hu/ orszagos-konyvtari-szabvanyositasi-bizottsag, a hatályos könyvtári szabványok jegyzéke pedig itt érhető el: http://www. oszk.hu/konyvtari-szabvanyok-szabalyzatok A szabványok a Könyvtártudományi Szakkönyvtárból (KSZK) kölcsönözhetők, a nyitvatartásról és a szolgáltatásokról bővebben a könyvtár honlapján lehet tájékozódni: http://ki.oszk.hu. 1. Állomány-nyilvántartás ISO 20775:2009(E) Information and documentation – Schema for holdings information 2. Bibliográfiai feldolgozás és adatcsere, transzliteráció ISO 10754:1996(E) Information and documentation – Extension of -

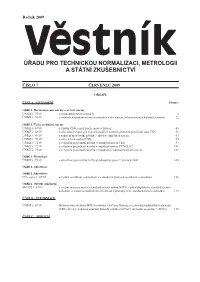

7 Červenec 2009

Ročník 2009 Úřadu pro technickou normalizaci, metrologii a státní zkušebnictví ČÍSLO 7 ČERVENEC 2009 OBSAH: ČÁST A – OZNÁMENÍ Strana: Oddíl 1. Harmonizované normy a určené normy ÚNMZ č. 75/09 o harmonizovaných normách 2 ÚNMZ č. 76/09 o zrušených harmonizovaných normách nebo zrušených harmonizacích platných norem 22 Oddíl 2. České technické normy ÚNMZ č. 67/09 o vydání ČSN, jejich změn, oprav a zrušení 43 ÚNMZ č. 68/09 o schválení evropských a mezinárodních norem k přímému používání jako ČSN 56 ÚNMZ č. 69/09 o zahájení zpracování návrhů českých technických norem 64 ÚNMZ č. 70/09 o návrzích na zrušení ČSN 94 ÚNMZ č. 71/09 o veřejném projednání návrhů evropských norem CEN 97 ÚNMZ č. 72/09 o veřejném projednání návrhů evropských norem CENELEC 101 ÚNMZ č. 73/09 o veřejném projednání návrhů evropských telekomunikačních norem 102 Oddíl 3. Metrologie ÚNMZ č. 74/09 o schválení typu měřidel a ES přezkoušení typu v I. čtvrtletí 2009 105 Oddíl 4. Autorizace Oddíl 5. Akreditace ČIA, o.p.s. č. 07/09 o vydání osvědčení o akreditaci a o ukončení platnosti osvědčení o akreditaci 106 Oddíl 6. Ostatní oznámení MO ČR č. 07/09 o vydání seznamu nových standardizačních dohod NATO, vydání doplňků ke standardizačním dohodám, o zrušení standardizačních dohod a přistoupení ke standardizačním dohodám 123 ČÁST B – INFORMACE ÚNMZ č. 07/09 Informačního střediska WTO o notifikacích Členů Dohody o technických překážkách obchodu (TBT), která je nedílnou součástí Dohody o zřízení Světové obchodní organizace (WTO) 129 ČÁST C – SDĚLENÍ ČÁST A – OZNÁMENÍ Oddíl 1. Harmonizované normy a určené normy OZNÁMENÍ č.