Chapter III State in the Making: the Kamata-Koches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

List of Candidates for the Post of Specialist Doctors Under NHM, Assam Sl Post Regd

List of candidates for the post of Specialist Doctors under NHM, Assam Sl Post Regd. ID Candidate Name Father Name Address No Specialist NHM/SPLST Dr. Gargee Sushil Chandra C/o-Hari Prasad Sarma, H.No.-10, Vill/Town-Guwahati, P.O.-Zoo 1 (O&G) /0045 Borthakur Borthakur Road, P.S.-Gitanagar, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-Assam, Pin-781024 LATE C/o-SELF, H.No.-1, Vill/Town-TARALI PATH, BAGHORBORI, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. GOPAL 2 NARENDRA P.O.-PANJABARI, P.S.-DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State- (O&G) /0002 SARMA NATH SARMA ASSAM, Pin-781037 C/o-Mrs.Mitali Dey, H.No.-31, Vill/Town-Tarunnagar, Byelane No. 2, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. MIHIR Late Upendra 3 Guwahati-78005, P.O.-Dispur, P.S.-Bhangagarh, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, (O&G) /0059 KUMAR DEY Mohan Dey State-Assam, Pin-781005 C/o-KAUSHIK SARMA, H.No.-FLAT NO : 205, GOKUL VILLA Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. MONTI LATE KIRAN 4 COMPLEX, Vill/Town-ADABARI TINIALI, P.O.-ADABARI, P.S.- (O&G) /0022 SAHA SAHA ADABARI, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781012 DR. C/o-DR. SANKHADHAR BARUA, H.No.-5C, MANIK NAGAR, Specialist NHM/SPLST DR. RINA 5 SANKHADHAR Vill/Town-R. G. BARUAH ROAD, GUWAHATI, P.O.-DISPUR, P.S.- (O&G) /0046 BARUA BARUA DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781005 C/o-ANUPAMA PALACE, PURBANCHAL HOUSING, H.No.-FLAT DR. TAPAN BANKIM Specialist NHM/SPLST NO. 421, Vill/Town-LACHITNAGAR FOURTH BYE LANE, P.O.- 6 KUMAR CHANDRA (O&G) /0047 ULUBARI, P.S.-PALTANBAZAR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State- BHOWMICK BHOWMICK ASSAM, Pin-781007 JUBAT C/o-Dr. -

The First Mohammedan Invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa Took

The first Mohammedan invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa took place during the reign of a king called Prithu who was killed in a battle with Illtutmish's son Nassiruddin in 1228. During the second invasion by Ikhtiyaruddin Yuzbak or Tughril Khan, about 1257 AD, the king of Kamrupa Saindhya (1250-1270AD) transferred the capital 'Kamrup Nagar' to Kamatapur in the west. From then onwards, Kamata's ruler was called Kamateshwar. During the last part of 14th century, Arimatta was the ruler of Gaur (the northern region of former Kamatapur) who had his capital at Vaidyagar. And after the invasion of the Mughals in the 15th century many Muslims settled in this State and can be said to be the first Muslim settlers of this region. Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. According to popular Chutia legend, Chutia king Birpal established his rule at Sadia in 1189 AD. He was succeeded by ten kings of whom the eighth king Dhirnarayan or Dharmadhwajpal, in his old age, handed over his kingdom to his son-in-law Nitai or Nityapal. Later on Nityapal's incompetent rule gave a wonderful chance to the Ahom king Suhungmung or Dihingia Raja, who annexed it to the Ahom kingdom.Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. -

Unit 2: Administration Under the Ahom Monarchy

Unit 2 Administration under the Ahom Monarchy UNIT 2: ADMINISTRATION UNDER THE AHOM MONARCHY UNIT STRUCTURE 2.1 Learning Objectives 2.2 Introduction 2.3 Administrative System of the Ahoms 2.3.1 Central Administration 2.3.2 Local Administration 2.3.3 Judicial Administration 2.3.4 Revenue Administration 2.3.5 Military Administration 2.4 Let Us Sum Up 2.5 10 Further Reading 2.6 Answers to Check Your Progress 2.7 Model Questions 2.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to: l Discuss the form of government in the Ahom administration, l Explain the central and local administration of the Ahoms, l Describe the judicial administration of the Ahoms, l Discuss the revenue administration of the Ahoms, l Explain the military administration of the Ahoms. 2.2 INTRODUCTION In the last unit, you have read about the Ahom Monarchy at its high peak. In this unit, we shall discuss the Ahom system of administration that stood at the base of the mighty Ahom Empire. We shall discuss the form of government, central and local administration, judicial administration revenue administration and military administration of the Ahoms. 22 History of Assam from the 17th Century till 1947 C.E. Administration under the Ahom Monarchy Unit 2 2.3 ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEM OF THE AHOMS The Ahoms are a section of the great Tai race. They established a kingdom in the Brahmaputra Valley in the early part of the 13th century and ruled Assam till the first quarter of the 19th century until the establishment of the authority of the British East India Company. -

Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17Th Century,Shayesta Khan Appointed As the Local Governor of Bengal

Class-4 BANGLADESH AND GLOBAL STUDIES ( Chapter 14- Our History ) Topic- 2“ The Middle Age” Lecture - 3 Day-3 Date-27/9/20 *** 1st read the main book properly. Middle Ages:The Middle Age or the Medieval period was a period of European history between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. Discuss about three kings of the Middle age: Shamsuddin Ilias Shah: 1.He came to power in the 14th century. 2.His main achievement was to keep Bengal independent from the sultans of Delhi. 3.Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah opened up Shahi dynasty. Isa Khan: 1.Isa Khan was the leader of the landowners in Bengal, called the Baro Bhuiyan. 2.He was the landlord of Sonargaon. 3.In the 16th century, he fought for independence of Bengal against Mughal emperor Akhbar. Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17th century,Shayesta Khan appointed as the local governor of Bengal. 2.At his time rice was sold cheap.One could get one mound of rice for eight taka only. 3.He drove away the pirates from his region. The social life in the Middle age: 1.At that time Bengal was known for the harmony between Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims. 2.It was also known for its Bengali language and literature. 3.Clothes and diets of Middle age wren the same as Ancient age. The economic life in the Middle age: 1.Their economy was based on agriculture. 2.Cotton and silk garments were also renowned as well as wood and ivory work. 3.Exports exceeded imports with Bengal trading in garments, spices and precious stones from Chattagram. -

Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley During Medieval Period Dr

প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo ISSN 2278-5264 প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo An Online Journal of Humanities & Social Science Published by: Dept. of Bengali Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Website: www.thecho.in Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley during Medieval Period Dr. Sahabuddin Ahmed Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Email: [email protected] Abstract After the fall of Srihattarajya in 12 th century CE, marked the beginning of the medieval history of Barak-Surma Valley. The political phenomena changed the entire infrastructure of the region. But the socio-cultural changes which occurred are not the result of the political phenomena, some extra forces might be alive that brought the region to undergo changes. By the advent of the Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, a qualitative change was brought in the region. This historical event caused the extension of the grip of Bengal Sultanate over the region. Owing to political phenomena, the upper valley and lower valley may differ during the period but the socio- economic and cultural history bear testimony to the fact that both the regions were inhabited by the same people with a common heritage. And thus when the British annexed the valley in two phases, the region found no difficulty in adjusting with the new situation. Keywords: Homogeneity, aryanisation, autonomy. The geographical area that forms the Barak- what Nihar Ranjan Roy prefers in his Surma valley, extends over a region now Bangalir Itihas (3rd edition, Vol.-I, 1980, divided between India and Bangladesh. The Calcutta). Indian portion of the region is now In addition to geographical location popularly known as Barak Valley, covering this appellation bears a historical the geographical area of the modern districts significance. -

Kerngeschichte Des Mahabharatas

www.hindumythen.de Buch 1 Adi Parva Das Buch von den Anfängen Buch 2 Sabha Parva Das Buch von der Versammlungshalle Buch 3 Vana Parva Das Buch vom Wald Buch 4 Virata Parva Das Buch vom Aufenthalt am Hofe König Viratas Buch 5 Udyoga Parva Das Buch von den Kriegsvorbereitungen Buch 6 Bhishma Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Bhishmas Buch 7 Drona Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Dronas Buch 8 Karna Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Karnas Buch 9 Shalya Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Shalyas Buch 10 Sauptika Parva Das Buch vom nächtlichen Überfall Buch 11 Stri Parva Das Buch von den Frauen Buch 12 Shanti Parva Das Buch vom Frieden Buch 13 Anusasana Parva Das Buch von der Unterweisung Buch 14 Ashvamedha Parva Das Buch vom Pferdeopfer Buch 15 Ashramavasaka Parva Das Buch vom Besuch in der Einsiedelei Buch 16 Mausala Parva Das Buch von den Keulen Buch 17 Mahaprasthanika Parva Das Buch vom großen Aufbruch Buch 18 Svargarohanika Parva Das Buch vom Aufstieg in den Himmel www.hindumythen.de Für Ihnen unbekannte Begriffe und Charaktere nutzen Sie bitte mein Nachschlagewerk www.indische-mythologie.de Darin werden Sie auch auf detailliert erzählte Mythen im Zusammenhang mit dem jeweiligen Charakter hingewiesen. Vor langer Zeit kam in Bharata, wie Indien damals genannt wurde, der Weise Krishna Dvaipayana Veda Vyasa zur Welt. Sein Name bedeutet ‘Der dunkle (Krishna) auf einer Insel (Dvipa) Geborene (Dvaipayana), der die Veden (Veda) teilte (Vyasa). Krishna Dvaipayana war die herausragende Gestalt jener Zeit. Er ordnete die Veden und teilte sie in vier Teile, Rig, Sama, Yajur, Atharva. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

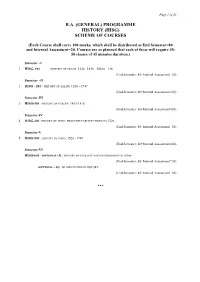

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings.