Unit 2: Administration Under the Ahom Monarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur's Ahoms

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur’s Ahoms - An Ethnographic Approach Barnali Chetia, PhD, Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Vadodara, India. Department of Linguistics Abstract- Mong Dun Shun Kham, which in Assamese means xunor-xophura (casket of gold), was the name given to the Ahom kingdom by its people, the Ahoms. The advent of the Ahoms in Assam was an event of great significance for Indian history. They were an offshoot of the great Tai (Thai) or Shan race, which spreads from the eastward borders of Assam to the extreme interiors of China. Slowly they brought the whole valley under their rule. Even the Mughals were defeated and their ambitions of eastward extensions were nipped in the bud. Rangpur, currently known as Sivasagar, was that capital of the Ahom Kingdom which witnessed the most glorious period of its regime. Rangpur or present day sivasagar has many remnants from Ahom Kingdom, which ruled the state closely for six centuries. An ethnographic approach has been attempted to trace the history of indigenous culture and traditions of Rangpur's Ahoms through its remnants in the form of language, rites and rituals, religion, archaeology, and sacred sagas. Key Words- Rangpur, Ahoms, Culture, Traditions, Ethnography, Language, Indigenous I. Introduction “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” -P.B Shelley Rangpur or present day Sivasagar was one of the most prominent capitals of the Ahom Kingdom. -

Detailed Project Report National Adaptation Fund

DETAILED PROJECT REPORT ON MANAGEMENT OF ECOSYSTEM OF KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK BY CREATING CLIMATE RESILIENT LIVELIHOOD FOR VULNERABLE COMMUNITIES THROUGH ORGANIC FARMING AND POND BASED PISCICULTURE for NATIONAL ADAPTATION FUND ON CLIMATE CHANGE SUBMITTED TO MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST & CLIMATE CHANGE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Indira Paryavaran Bhavan, Jorbagh Road, New Delhi - 110003 Page | 1 Title of Project/Programme: Management of ecosystem of Kaziranga National Park by creating climate resilient livelihood for vulnerable communities through organic farming and pond based pisciculture Project/Programme Objective/s: The proposed project entails the following broad objectives: ► Rejuvenating selected beels which are presently completely dry and doesn’t hold any water, which includes de-siltation of the beel to increase the depth and thus the augment the water holding capacity of the beel. ► Increase in livelihood option for vulnerable communities living in vicinity of Kaziranga National Park through organic farming and pond based fisheries ► Management of watersheds through check dams and ponds Organic farming is envisaged for the vulnerable communities within the southern periphery of the national park. A focused livelihood generation from fisheries is also envisaged for the fishing communities living in the in the north bank of Brahmaputra. Project/ Programme Sector: ► Forestry, agriculture, fisheries and ecosystem Name of Executing Entity/ies/Department: ► Kaziranga National Park (KNP) under Department of Environment & Forests (DoEF), Government of Assam. Beneficiaries: ► Vulnerable communities living in the periphery of Kaziranga National Park (KNP), Assam Project Duration: 3 years Start Date: October 2016 End Date: September 2019 Amount of Financing Requested (INR.): 2,473.08 Lakhs Project Location: The list of finalised project sites are as under. -

City Sanitation Plan

Pollution Control Board, Assam Conservation of River Kolong, Nagaon Preparation of Detailed Project Report City Sanitation Plan December 2013 Joint Venture of THE Louis Berger Group, INC and DHI (India) Water & Environment Pvt. Ltd. City Sanitation Plan Photos on the front page are taken by the project field team in Nagaon town during visits in year 2013. ii City Sanitation Plan CONTENTS Salient Features of the Project .................................................................................................. viii Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... x Check List for City Sanitation Plan ............................................................................................. xi 1 About the Project Area ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 Authority for Preparation of Project ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Composition of the Team for CSP ................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Description of the Project Area ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3.1 Description of the Polluted Stretch ................................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Justification for selecting the Town for Project Formulation under NRCP/NGRBA -

A Study of Towns, Trade and Taxation System in Medieval Assam Pjaee, 17 (7) (2020)

A STUDY OF TOWNS, TRADE AND TAXATION SYSTEM IN MEDIEVAL ASSAM PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) A STUDY OF TOWNS, TRADE AND TAXATION SYSTEM IN MEDIEVAL ASSAM 1Ebrahim Ali Mondal, Assistant Professor of History , B.N. College, Dhubri Assam, India E-mail:[email protected] Ebrahim Ali Mondal, Assistant Professor of History , A Study of Towns, Trade and Taxation system in Medieval Assam--Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords- Towns; Trade; Artisans; Crafts; Taxation; production; Sources Abstract: The present paper an attempt has been made to analyse the growth of towns and trading activities as well as the system of taxation system in Assam during the period under study. The towns were filled by the various kinds of artisans and they produced numerous types of crafts such as textiles Sericulture, Dyeing, Gold and Silver works, Copper and Brass works, Iron works, Gunpowder, Bow and Arrow making, Boat-building, Woodcraft, Pottery and Clay modeling, Brick making, Stone works, Ivory, and carving works. The crafts of Assam were much demand in local markets as well as other regions of India. The towns gradually acquired the status of urban centres of production and distribution. Regular, weekly and fortnightly markets as well as fairs from time to time were held throughout Assam where the traders purchased with their goods for sale. In the business community which was included the whole-sellers, retailers and brokers; they all had a flourishing business. Therefore, the towns were the one of the major source of income as a result the kings of Assam had built several custom houses, many gateways and toll gates in order to raise taxes of imports and exports and to check the activities of the merchants' class. -

Finance Consultant, NTCP

Provisionally shortlisted candidates for Interview for the Post of Finance Consultant, NTCP under NHM, Assam Instruction: Candidates shall bring all relevant testimonials and experience certificates in original to produce before selection committee along with a set of self attested photo copies for submission at the time of interview. Shortlisting of candidates have been done based on the information provided by the candidates and candidature is subject to verification of documents at the time of interview. Date of Interview : 30/01/2018 Time of Interview : 11:30 AM (Reporting Time - 11:00 AM) Venue : Office of the Mission Director, NHM, Assam, Saikia Commercial Complex, Christianbasti, Guwahati-5 Sl Regd. ID Candidate Name Father Name Address No. C/o-S/o A RAMAIAH, H.No.-22-1117,, Vill/Town-SBI COLONY,, NHM/FCNTC A KISHORE 1 A RAMAIAH P.O.-CHITTOOR, P.S.-CHITTOOR, Dist.-CHITTOOR DISTRICT, P/0048 KUMAR A.P., State-ANDRA PRADESH, Pin-517001 C/o-Mahesh Chandra Sarmah Bagharbori Tiniali Homeo College NHM/FCNTC Mahesh Chandra 2 Abhijit Sarmah Path Milijuli Path, H.No.-23, Vill/Town-Guwahati, P.O.-Panjabari, P/0102 Sarmah P.S.-Dispur, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-Assam, Pin-781037 C/o-Jaladhar Narzary, H.No.-9, Vill/Town-Salguri, P.O.- NHM/FCNTC 3 Alayaran Narzary Jaladhar Narzary Choraikhola, P.S.-Kokrajhar, Dist.-Kokrajhar, State-Assam, Pin- P/0071 783376 C/o-BISHWANATH PAUL, H.No.-120, Vill/Town-GOLAGHAT, NHM/FCNTC BISHWANATH 4 ANESH PAUL P.O.-BENGENAKHOWA, P.S.-GOLAGHAT, Dist.-Golaghat, State- P/0028 PAUL ASSAM, Pin-785621 C/o-UMA RANI DAS, H.No.-16, Vill/Town-BISHNU RABHA NHM/FCNTC LT SARBESWAR 5 ANJALI DAS PATH BELTOLA TINIALI, P.O.-BELTOLA TINIALI, P.S.- P/0111 DAS BASISTHA, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781028 C/o-Mr. -

Revenue and Fiscal Regulation of the Ahoms Dr. Meghali Bora

Social Science Journal of Gargaon College, Volume V • January, 2017 ISSN 2320-0138 Revenue and Fiscal Regulation of The Ahoms *Dr. Meghali Bora Abstract The Ahom kings who ruled over Assam for six hundred years left their indelible contributions not only on the life and culture of the people but also tried their best to improve the economy of the state by maintaining a rigid and peculiar system of revenue administration. For proper functioning of revenue and fiscal administration the Ahom kings introduced well knitted paik and khel system which was the backbone of the Ahom economy. The Ahom kings also received a good amount of revenue by collecting different kinds of taxes from hats, ghats, phats, beels, chokis and tributes from subordinates chiefs and kingdoms. It was only because of having such affluent economy the Ahoms could rule in Assam for about six hundred years. Key words : Revenue administration, Paik and Khel system and Trade statistics. Introduction : In the beginning of the Ahom reign there was no clear cut policy on civil and revenue administration. The first step towards the creation of a separate revenue department was taken by Pratap Singha (1603-41) who created the posts of Barbarua and Barphukon. The Barbarua was the chief executive revenue and judicial officer of Upper Assam and the Barphukan posted at Guwahati was of Lower Assam. Later king Rudra Singha (1696-1714) completed the process of revenue administration by creating two central revenue departments, one at Rangpur (Upper Assam) and another at Guwahati (Lower Assam). There were three main sources from which the Ahom kings collected their revenue and these were personal service, produce of the land and cash. -

History of Medieval Assam Omsons Publications

THE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM ( From the Thirteenth to the Seventeenth century ) A critical and comprehensive history of Assam during the first four centuries of Ahom Rule, based on original Assamese sources, available both in India and England. DR. N.N. ACHARYYA, M.A., PH. D. (LOND.) Reader in History UNIVERSITY OF GAUHATI OMSONS PUBLICATIONS T-7, Rajouri Garden, NEW DELHI-110027 '~istributedby WESTERN BOOK DWT Pan Bazar, Gauhati-78 1001 Assam Reprint : 1992 @ AUTHOR ISBN : 81 -71 17-004-8 (HB) Published by : R. Kumar OMSONS I'UBLICATIONS, T-7,RAJOURl GARDEN NEW DELHI- I 10027. Printed at : EFFICIENT OFFSET PRINTERS 215, Shahrada Bagh Indl. Complex, Phase-11, Phone :533736,533762 Delhi - 11 0035 TO THE SACRED MEMORY OF MY FATHER FOREWORD The state of Assam has certain special features of its own which distinguish it to some extent from the rest of India. One of these features is a tradition of historical writing, such as is not to be found in most parts of the Indian sub-continent. This tradition has left important literary documents in the form of the Buranjis or chronicles, written in simple straightforward prose and recording the historical traditions of the various states and dynasties which ruled Assam before it was incorporated into the domains of the East India Company. These works form an imperishable record of the political history of the region and throw much light also upon the social life of the times. It is probable, though not proven with certainty, that this historical tradition owes its inception to the invasion of the Ahoms, who entered the valley of the Brahmaputra from what is now Burma in 1228, for it is from this momentous year that the Buranji tradition dates. -

A Study Into the Ahom Military System in Medieval Assam

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 6 ǁ June. 2015ǁ PP.17-22 A study into the Ahom Military System in Medieval Assam Nilam Hazarika Naharkatiya College, Dibrugarh University ABSTRACT: A study into the Ahom Military System in Medieval Assam Assam since the coming of the Ahoms and the establishment of the state in the north eastern region of India experienced a number of invasions sponsored by the Muslim rulers of Bengal and in the first half of the 16th century by the Mughals a numerous times in their six hundred years of political existence. In almost all the invasions the Ahoms forces could stand before the invading forces with much strength except one that of Mir Jumla. This generates a general interest into the military system and organization of the Ahoms. Interestingly during the medieval period the Mughals could easily brought about a political unification of India conquering a vast section of the Indian subcontinent. Ahoms remarkably could manage to keep a separate political identity thwarting all such attempts of the Mughals to invade and subjugate the region. This generates an enquiry into the Ahom military administration, its discipline, ways of recruitment, weapons and method of maintaining arsenals and war strategy. Keywords: Paik, Gohains, Buragohain, Phukons, Hazarika, Saikia, Bora, Hilioi I. A STUDY INTO THE AHOM MILITARY SYSTEM IN THE MEDIEVAL TIMES Assam since the coming of the Ahoms and the establishment of the state in the north eastern region of India experienced a number of invasions sponsored by the Muslim rulers of Bengal and in the first half of the 16th century by the Mughals a numerous times in their six hundred years of political existence. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

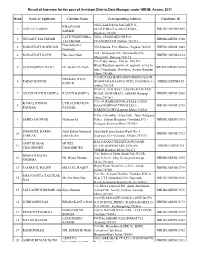

Assiatant District Data Manager Result Marks

Result of Interview for the post of Assistant District Data Manager under NRHM, Assam, 2011 Rank Name of Applicant Gurdian Name Corresponding Address Candidate ID VILL-KALPANA NAGAR,P.O.- KHASNOOR 1 ASIF UZ ZAMAN GOALPARA,P.S.-GOALPARA, NRHM/ADDM/6669 AHMED Goalpara,783101 LATE PHANINDRA VILL: CHANDKUCHI,P.O: 2 GUNAJIT TALUKDAR NRHM/ADDM/1980 TALUKDAR CHANDKUCHI, Nalbari,781335 Phanindra dev 3 NABAJYOTI GOSWAMI Vill-Nasatra, P.O.-Hatbor, ,Nagaon,782136 NRHM/ADDM/1485 Goswami Vill.- Kuiyapani,PO- Aulachowka,PS- 4 NABAJYOTI NATH Hareswar Nath NRHM/ADDM/6814 Mangaldai, Darrang,784125 C/o Tridip Barua, Flat no. 204, IIE Block,Rajdhani apartment, opposite seven to 5 SUDAKSHINA NATH Dr. Manik Ch. Nath NRHM/ADDM/10740 nine, Ganeshguri, Guwahati, Assam, Kamrup Metro,781006 C/O:RUPALI BARUAH,NARSING GAON, PRANAB JYOTI 6 TAPAN KONCH BHIMPARA,NAUPUKHURI,TINSUKIA,Ti NRHM/ADDM/102 KONCH nsukia,786125 HNO-12, 5TH BYE LANE(W),RAJGARH 7 ANJAN JYOTI BAISHYA RAJANI BAISHYA ROAD, GUWAHATI, ASSAM, Kamrup NRHM/ADDM/2686 Metro,781003 C/O- SURABHI BOOK STALL (UPEN KAMAL KUMAR LT KALICHARAN 8 DAS),NARENGI TINIALI,P.O.- NRHM/ADDM/2758 PATHAK PATHAK NARENGI,GHY,Kamrup Metro,781026 H/No.-10 Sankar Azan Path , ,Near Hatigaon 9 SAHID ANOWAR Mahrum Ali Police Station,Hatigaon, Guwahati,P.O.- NRHM/ADDM/9945 Hatigaon,Kamrup Metro,781038 SHAJEDUL KARIM Abul Kalam Manjurul Shajedul Karim Sarkar,Ward No:-4, 10 NRHM/ADDM/2723 SARKAR Islam Sarkar Gauripur,P.O:-Gauripur, Dhubri,783331 KALYANKUCHI,SATGAON,NEAR AMIT KUMAR MUKUL 11 STATE DISPENSARY,UDYAN NRHM/ADDM/395 CHAUDHURY CHAUDHURY VIHAR,Kamrup Metro,781171 C/o- Indrajeet Dutta,Junali Pah, R.G.B. -

Agricultural Landuse Pattern of Nagaon District, Assam: Present Status and Changing Pjaee, 17 (7) (2020) Scenario

AGRICULTURAL LANDUSE PATTERN OF NAGAON DISTRICT, ASSAM: PRESENT STATUS AND CHANGING PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) SCENARIO AGRICULTURAL LANDUSE PATTERN OF NAGAON DISTRICT, ASSAM: PRESENT STATUS AND CHANGING SCENARIO Banashree Saikia1, D. Sahariah2 Research Scholar and Professor Department of Geography, Gauhati University E-mail:[email protected] Banashree Saikia1, D. Sahariah2: Agricultural Landuse Pattern of Nagaon District, Assam: Present Status and Changing Scenario-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Agriculture, landuse, cropping pattern ABSTRACT Agricultural landuse pattern of the district is mainly influenced by the fertile plain along with favourable climatic condition of the region which permits to cultivate different varieties of crops in different season. Rice, wheat, pulses, sugarcane, spices, fruits and vegetables, different oilseeds (rape and mustard, sesame) and jute etc. are extensively cultivated all over the district. The various socio-economic factors are also responsible for producing diverse agricultural land use pattern in the district. As agriculture is considered as a primary economic activity to sustain their livelihood of rural people, therefore cultivation of different varieties of crops produce diverse landuse pattern in the district. This study is an attempt to identify the intra-district variation in agricultural cropping patter and their spatio- temporal changes over time. Introduction In Nagaon district of Assam, agriculture and its allied activities played an important role in the socio-economic development as this sector is considered as a major contributor towards the district economy. Agriculture is considered the backbone of rural economy of the district as it provides livelihoods of rural people. In Assam, generally agricultural land use means the cultivation of soil for growing crops to fulfill the human needs only (Das, 1984). -

5. Indian History -2- Iv Semester

INDIAN HISTORY - 2 IV SEMESTER (2019 Admission) BA HISTORY Core Course HIS4 B06 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT School of Distance Education Calicut University P.O., Malappuram, Kerala, India - 673 635 19309 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT School of Distance Education Study Material IV SEMESTER (2019 Admission) BA HISTORY Core Course (HIS4 B06) INDIAN HISTORY - 2 Prepared by: Sri.Vivek. A. B, Assistant Professor, School of Distance Education, University of Calicut. Scrutinized by: Dr. Santhoshkumar L, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Govt. College for Women, Thiruvananthapuram. Indian History - 2 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS INTERPRETING EARLY MODULE I MEDIEVAL INDIAN 5 HISTORY DELHI SULTANATE, VIJAYA NAGARA MODULE II EMPIRE AND BHAMANI 20 KINGDOM FORMATION OF MODULE III MUGHAL EMPIRE 116 RELIGIOUS IDEAS AND MODULE IV BHAKTHI TRADITION 200 Indian History - 2 3 School of Distance Education Indian History - 2 4 School of Distance Education MODULE I INTERPRETING EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIAN HISTORY Introduction The early medieval period spanning from c.600CE to 1300C is to be situated between the early his-torical and medieval. Historians are unanimous on the fact that this phase in India history had a distinct identity and as such differed from the preceding early historical and succeeding medieval. This in turn brings home the presence of the elements of change and continuity in Indian history. It is identified as a phase in the transition to the medieval. Perception of a unilinear and uniform pattern of historical development is challenged. Changes are identified not merely in dynastic upheavals but are also located in socio-economic, political and cultural conditions.