The Night of the Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes and Superheroes Intersession 2021 Dr. Adrian Mioc Class: Tue 9:30 AM -12:30 PM, Th 9:30 AM - 12:30 PM Office: UC 3314 Office Hours: Thu 12:30-2:30 PM Email: [email protected] Prerequisite(s): At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1020-1999 or permission of the Department. Although this academic year might be different, Huron University is committed to a thriving campus. We encourage you to check out the Digital Student Experience website to manage your academics and well-being. Additionally, the following link provides available resources to support students on and off campus: https://www.uwo.ca/health/. Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam General Course Description This course aims to explore the figure of the hero and superhero as it evolves and is depicted in contemporary comic books as well as in other forms of popular culture such as movies and TV series. Methodologically, it will combine the study of literature with contemporary popular culture while incorporating a theoretical component as well. Specific Focus: In the beginning, we will briefly explore myths that are relevant and will help us understand the figure of the modern day superhero. After a quick historical exploration, which will offer a substantial foundation for the study of the 20th and 21st-century manifestation of the superheroes, the main focus of this course will be placed on the problematic of this figure. Besides well-known characters (Superman, Batman and Spiderman), we will tackle less-spoken-about figures such as Jessica Jones or Harley Qinn. -

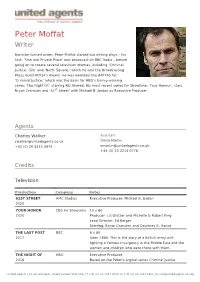

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

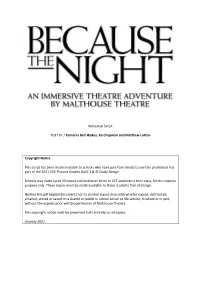

Rehearsal Script TEXT by / Kamarra Bell-Wykes, Ra Chapman and Matthew Lutton Copyright Notice This Script Has Been Made Availabl

Rehearsal Script TEXT BY / Kamarra Bell-Wykes, Ra Chapman and Matthew Lutton Copyright Notice This script has been made available to schools who have purchase tickets to see this production has part of the 2021 VCE Theatre Studies (Unit 3 & 4) Study Design. Schools may make up to 20 copies and distribute them to VCE students in their class, for this express purpose only. These copies must be made available to those students free of charge. Neither this pdf (digital document) nor its printed copies may otherwise be copied, distributed, emailed, stored or saved on a shared or public or school server or file service, in whole or in part, without the express prior written permission of Malthouse Theatre. This copyright notice must be preserved in its entirety on all copies. January 2021 BECAUSE THE NIGHT PROLOGUE The audience are asked to cloak their belongings and leave their phones behind. Audience are given a mask as FOH speaks to them individually: When you enter You can explore every room You can walk wherever you want Whenever want There is no correct way to experience this show Once you enter The only rules are: No speaking No phone And no touching the performers If you need help Or a guide At any time Approach those with the white mask They will help you Audience are invited into the one of the corridors that lead to either the “Gym”, “Royal office” or “The Bedroom” BRIEFING CORRIDOR When all the audience are in the briefing corridors, we hear the sounds of the forest. -

TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy®

Contact: An Tran Public Relations Manager + 1 818 841 7070 [email protected] Reegan Koester Corporate Communications Manager +49 89 3809 1768 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy® • ARRI receives highest TV technology recognition for outstanding achievement in engineering development • Since 2010, ALEXA has been the camera system of choice on numerous television and feature productions • ALEXA’s digital technology has been embraced by the television industry for its stunning image quality, reliability, and ease October 26, 2017, Los Angeles – At the 69th Engineering Emmy® Awards Ceremony in Hollywood, the Television Academy recognized ARRI with the most prestigious television accolade for outstanding achievement in engineering development for its ALEXA digital motion picture camera system. On October 25, 2017, at the Loews Hollywood Hotel, actress Kirsten Vangsness, who presented the award, said: “The ALEXA camera system represents a transformative technology in television due to its excellent digital imaging capabilities coupled with a completely integrated postproduction workflow. In addition, a cohesive pipeline, the onboard recording of both raw and a compressed video image, and an easy-to-use interface contributed to the television industry’s widespread adoption of the ARRI ALEXA.” The Engineering Award was accepted by ARRI´s Harald Brendel, Teamlead Image Science, and Frank Zeidler, Senior Manager Technology and Deputy Head of R&D – both members of the ALEXA development team – as well as Glenn Kennel, President of ARRI Inc. In his acceptance speech, Harald Brendel mentioned ARRI’s 100-year legacy of laying the foundation for the ALEXA and keeping the camera today as the industry workhorse. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Time Bruce's Chords

4th Of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) C F C F C Guitar 1: ------|--8-8<5------|---------------|-------------|---------------| -5----|--------8<6--|-5-/-8—6-------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------7-----|-5-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---7-5-5-----|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---------7-5vvvv-------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|-------------8-| Guitar 2: All ---5--|-8-----------|-18<15---------|-------------|-15-12-12-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------13-12---|-------------|-15-13-13-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------------13<15-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| F C F C Guitar 1: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-5vvv\3-|--------------3-|-3/5-8-10/8------| Time Guitar 2: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-7\5----|-17\15<13-15-17-|---------|-------| |-----7--|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| Sandy C F C Sandy the fireworks are hailin' over Little Eden tonight Am Gsus G Forcin' a light -

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil 2

Copyright HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB www.tolkien.co.uk Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014 First published by George Allen & Unwin 1962 Copyright © The Tolkien Estate Limited 1962, 2014 Illustrations copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 1962 Further copyright notices appear here and ‘Tolkien’® are registered trade marks of The Tolkien Estate Limited A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e- book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down- loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 97800057271 Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007584697 Version: 2014-09-12 CONTENTS Cover Title Page Copyright Introduction Preface 1. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil 2. Bombadil Goes Boating 3. Errantry 4. Princess Mee 5. The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late 6. The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon 7. The Stone Troll 8. Perry-the-Winkle 9. The Mewlips 10. Oliphaunt 11. Fastitocalon 12. Cat 13. Shadow-Bride 14. The Hoard 15. The Sea-Bell 16. The Last Ship Commentary Preface The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Bombadil Goes Boating Errantry Princess Mee The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon The Stone Troll Perry-the-Winkle The Mewlips Oliphaunt Fastitocalon Cat Shadow-Bride The Hoard The Sea-Bell The Last Ship Gallery Appendix I. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

THE CAMPUS Community April 5, 2001 Since 1876

Vol. 124, Issue 19 Serving the Allegheny College Thursday THE CAMPUS community April 5, 2001 since 1876 I do not agree with a word you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it. - Voltaire Frat Members To ROCKIN' D.C. Fill RA Positions By ERICA ERWIN would be placed in the fraternity News Editor houses, brothers in Phi Psi and Delta Tau Delta were concerned about After a brief search process, the whether a brother or a non-member Office of Residence Life has placed would be given the position. two , students, juniors Russ Adkins Because of the tight-knit nature of a and Jake Nagel, in Resident Advisor fraternity, many brothers were con- positions in the Phi Kappa Psi and cerned that a non-member wouldn't Delta Tau Delta fraternity houses. "fit in." "I think it was the goal of all Both students are also brothers of the involved to put a brother in the posi- fraternities, respectively. tion," said Adkins. "It was just a The selection process was a joint matter of finding someone qualified. effort between the Office of I'm glad we could do this :Amicably." Residence Life and Greek Life. The "We took into consideration their students will begin to take on their concerns," said Miller. "We took new roles at the beginning of next their comments and feedback into semester. said Director of Residence consideration when deciding, and Life Joe Miller. told them we would consider having A group of 29 Allegheny students traveled to Washington, D.C. -

Indice: 0. Philip K. Dick. Biografía. La Esquizofrenia De Dick. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni 1

Indice: 0. Philip K. Dick. Biografía. La esquizofrenia de Dick. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni 1. El cuento final de todos los cuentos. Philip K. Dick. 2. El impostor. Philip K. Dick. 3. 20 años sin Phil. Ivan de la Torre. 4. La mente alien. Philip K. Dick. 5. Philip K. Dick: ¿Aún sueñan los hombres con ovejas de carne y hueso? Jorge Oscar Rossi. 6. Podemos recordarlo todo por usted. Philip K. Dick. 7. Philip K. Dick en el cine 8. Bibliografía general de Philip K. Dick PHILIP K. DICK. BIOGRAFÍA. LA ESQUIZOFRENIA DE DICK. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni Biografía: Philip. K. Dick (1928-1982) Nació prematuramente, junto a su hermana gemela Jane, el 2 de marzo 1928, en Chicago. Jane murió trágicamente pocas semanas después. La influencia de la muerte de Jane fue una parte dominante de la vida y obra de Philp K. Dick. El biógrafo Lawrence Sutin escribe; ...El trauma de la muerte de Jane quedó como el suceso central de la vida psíquica de Phil Dos años más tarde los padres de Dick, Dorothy Grant y Joseph Edgar Dick se mudaron a Berkeley. A esas alturas el matrimonio estaba prácticamente roto y el divorcio llegó en 1932, Dick se quedó con su madre, con la que se trasladó a Washington. En 1940 volvieron a Berkeley. Fue durante este período cuando Dick comenzó a leer y escribir ciencia ficción. En su adolescencia, publicó regularmente historias cortas en el Club de Autores Jovenes, una columna el Berkeley Gazette. Devoraba todas las revistas de ciencia-ficción que llegaban a sus manos y muy pronto empezó a ser influido por autores como Heinlein y Van Vogt.