Perspectives on the Role of a Central Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russian-Chinese Oil Politik

China-Russia Relations: The Russian-Chinese Oil Politik Yu Bin Associate Professor, Wittenberg University The specter of oil is haunting the world. The battle of oil, however, is not just being waged by oilmen from Texas and done with “shock-and-awe” in the era of preemption. Nor does it have anything to do with the billion-dollar contract awarded to the U.S. firm Halliburton for the reconstruction of postwar Iraq. This time, oil, or lack of it, is clogging the geostrategic pipeline between the world’s second largest oil producer (Russia) and second largest oil importing state (China) as they haggle over the future destination of Siberia’s vast oil reserves. To be sure, the “oil politik” between Moscow and Beijing is far from a full-blown crisis. Indeed, China-Russia relations during the third quarter were marked by dynamic interactions and close coordination over multilateral issues of postwar Iraq, the Korean nuclear crisis, and institution building for the SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization). Russia’s energy realpolitik, however, has led to such a psychological point that for the first time, a generally linear, decade-long emerging Russian-Chinese strategic partnership, or honeymoon, seems arrested and is being replaced by a routine, boring, or even jolting marriage of necessity in which quarrels and conflicts are part normal. Business still as Usual Unlike the more turbulent and/or spectacular second quarter, the post-Iraq and post- SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) third quarter seemed normal for Russia and China, at least on the surface. All border checkpoints were reopened with busier transactions to make up for the losses suffered during the SARS epidemic. -

Comparative Connections

Pacific Forum CSIS Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations edited by Brad Glosserman Vivian Brailey Fritschi 3rd Quarter 2003 Vol. 5, No. 3 October 2003 www.csis.org/pacfor/ccejournal.html Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, Hawaii, the Pacific Forum CSIS operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1975, the thrust of the Forum’s work is to help develop cooperative policies in the Asia-Pacific region through debate and analyses undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate arenas. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic/business, and oceans policy issues. It collaborates with a network of more than 30 research institutes around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating its projects’ findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and publics throughout the region. An international Board of Governors guides the Pacific Forum’s work; it is chaired by Brent Scowcroft, former Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs. The Forum is funded by grants from foundations, corporations, individuals, and governments, the latter providing a small percentage of the forum’s $1.2 million annual budget. The Forum’s studies are objective and nonpartisan and it does not engage in classified or proprietary work. Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Edited by Brad Glosserman and Vivian Brailey Fritschi Volume 5, Number 3 Third Quarter 2003 Honolulu, Hawaii October 2003 Comparative Connections A Quarterly Electronic Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Bilateral relationships in East Asia have long been important to regional peace and stability, but in the post-Cold War environment, these relationships have taken on a new strategic rationale as countries pursue multiple ties, beyond those with the U.S., to realize complex political, economic, and security interests. -

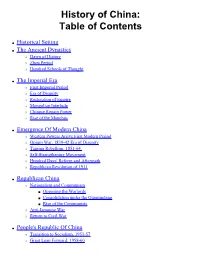

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Regional Seminars Support Launch of Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey N January and February, the IMF’S Statistics Debt (Bonds, Notes, Money Market Instruments)

IMF Statistics Department Regional seminars support launch of Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey n January and February, the IMF’s Statistics debt (bonds, notes, money market instruments). It does IDepartment organized five regional seminars for not include the typically less volatile direct investment, country authorities in support of the 2001 which features a more lasting interest between the two Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS). parties, or foreign reserves, which are controlled by the The survey is the second undertaken by the IMF to monetary authorities. improve the measurement of portfolio flows across In response to concerns about asymmetries in global national borders and to deepen understanding of how balance of payments statistics in the late 1980s, an inter- international financial markets operate. The seminars national working party, headed by Baron Jean Godeaux, were designed to explain the purpose and methodol- former Governor of the National Bank of Belgium, rec- ogy of the survey and allow officials who took part in ommended undertaking a coordinated survey of cross- the first survey, held in 1997, to share their experiences border security positions. In the mid-1990s, at the request and insights with first-time participants. of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics, Over 70 jurisdictions participated in the seminars then IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus invited (see box, page 109). The Belgian National Bank hosted major investing countries to participate in the first such two seminars covering the European countries, the survey, organized under the auspices of the IMF, to United States, Canada, the Middle East, and Africa. improve coverage worldwide and spread best practices in The Central Bank of Costa Rica hosted a seminar for compiling data on cross-border portfolio investments. -

119516 Factions and Finance in China Elite Conflict and Inflation.Pdf

P1: KNP 9780521872577pre CUFX179/Shih 978 0 521 87257 7 October 4, 2007 21:21 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: KNP 9780521872577pre CUFX179/Shih 978 0 521 87257 7 October 4, 2007 21:21 Factions and Finance in China The contemporary Chinese financial system encapsulates two possible futures for China’s economy. On the one hand, extremely rapid financial deepening accompanied by relatively stable prices drives a vigorous growth trajectory that will one day make China the world’s largest economy. On the other hand, the colossal store of nonperforming loans in the banking sector augurs a troubling future. Factions and Finance in China inquires how elite factional politics has given rise to both of these outcomes since the reform in 1978. The competition over monetary policies between general- ists in the Chinese Communist Party and politically engaged technocrats has time and again prevented inflation from spinning out of control. Nonetheless, elite politicians, whether party generalists or technocrats, continue to see the banking sector as a ready means of political capital, thus continuing government intervention in the banking sector and slow- ing down reform. Through quantitative analysis and in-depth case studies, Shih shows that elite politics has exerted a profound impact on monetary policies and banking institutions in contemporary China. Victor C. Shih is a political economist at Northwestern University specializ- ing in China. An immigrant to the United States from Hong Kong, Dr. Shih received his doctorate in government from Harvard University, where he researched banking sector reform in China with the support of the Jacob K. -

Civil-Military Change in China: Elites, Institutes, and Ideas After the 16Th Party Congress

CIVIL-MILITARY CHANGE IN CHINA: ELITES, INSTITUTES, AND IDEAS AFTER THE 16TH PARTY CONGRESS Edited by Andrew Scobell Larry Wortzel September 2004 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Offi ce by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or by e-mail at [email protected] ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-165-2 ii CONTENTS Foreword Ambassador James R. Lilley............................................................................ v 1. Introduction Andrew Scobell and Larry Wortzel................................................................. 1 2. Party-Army Relations Since the 16th Party Congress: The Battle of the “Two Centers”? James C. -

China's Rulers: the Fifth Generation

CHINA’S RULERS: THE FIFTH GENERATION TAKES POWER (2012–13) Michael Dillon This project is funded by A project implemented by The European Union Steinbeis GmbH & Co. KG für Technologietransfer © Europe China Research and Advice Network, 2012 This publication may be reproduced for personal and educational use only. Commercial copying, hiring or lending of this publication is strictly prohibited. Europe China Research and Advice Network 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE +44 (0) 20 7314 3659 [email protected] www.euecran.eu Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................ 4 ExecutIve Summary ........................................................................................ 6 Key PRC PolItIcal BodIes .................................................................................. 7 Timetable for Leadership Changes .................................................................. 8 Introduction ................................................................................................... 9 1 Change and ContInuity ............................................................................... 11 2 Senior PolItIcal Appointments .................................................................... 14 3 PolItIcal GeneratIons In China .................................................................... 16 4 CCP FactIons and the SuccessIon Process ................................................... 17 5 Key Issues ................................................................................................. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement February 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 43 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 48 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 55 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 59 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 February 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Civil-Military Change in China: Elites, Institutes, and Ideas After the 16Th Party Congress

CIVIL-MILITARY CHANGE IN CHINA: ELITES, INSTITUTES, AND IDEAS AFTER THE 16TH PARTY CONGRESS Edited by Andrew Scobell Larry Wortzel September 2004 Visit our website for other free publication downloads Strategic Studies Institute Home To rate this publication click here. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or by e-mail at [email protected] ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-165-2 ii CONTENTS Foreword Ambassador James R. Lilley ............................................................................ v 1. Introduction Andrew Scobell and Larry Wortzel ................................................................ -

Wilfried Loth Building Europe

Wilfried Loth Building Europe Wilfried Loth Building Europe A History of European Unification Translated by Robert F. Hogg An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-042777-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-042481-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-042488-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image rights: ©UE/Christian Lambiotte Typesetting: Michael Peschke, Berlin Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Abbreviations vii Prologue: Churchill’s Congress 1 Four Driving Forces 1 The Struggle for the Congress 8 Negotiations and Decisions 13 A Milestone 18 1 Foundation Years, 1948–1957 20 The Struggle over the Council of Europe 20 The Emergence of the Coal and Steel Community -

The 16Th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Formal Institutions and Factional Groups ZHIYUE BO*

Journal of Contemporary China (2004), 13(39), May, 223–256 The 16th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: formal institutions and factional groups ZHIYUE BO* What was the political landscape of China as a result of the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)? The answer is two-fold. In terms of formal institutions, provincial units emerged as the most powerful institution in Chinese politics. Their power index, as measured by the representation in the Central Committee, was the highest by a large margin. Although their combined power index ranked second, central institutions were fragmented between central party and central government institutions. The military ranked third. Corporate leaders began to assume independent identities in Chinese politics, but their power was still negligible at this stage. In terms of informal factional groups, the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) Group was the most powerful by a large margin. The Qinghua Clique ranked second. The Shanghai Gang and the Princelings were third and fourth, respectively. The same ranking order also holds in group cohesion indexes. The CCYL Group stood out as the most cohesive because its group cohesion index for inner circle members alone was much larger than those of the other three factional groups combined. The Qinghua Clique came second, and the Shanghai Gang third. The Princelings was hardly a factional group because its group cohesion index was extremely low. These factional groups, nevertheless, were not mutually exclusive. There were significant overlaps among them, especially between the Qinghua Clique and the Shanghai Gang, between the Princelings and the Qinghua Clique, and between the CCYL Group and the Qinghua Clique. -

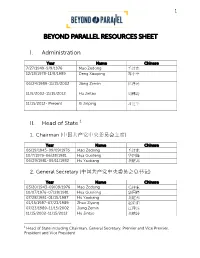

Beyond Parallel Resources Sheet

1 BEYOND PARALLEL RESOURCES SHEET I. Administration Year Name Chinese 7/27/1949-9/9/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 12/18/1978-11/8/1989 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 06/24/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/5/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 11/15/2012- Present Xi Jinping 习近平 II. Head of State 1 1. Chairman (中国共产党中央委员会主席) Year Name Chinese 06/19/1945-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/7/1976-06/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 06/29/1981-09/11/1982 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 2. General Secretary (中国共产党中央委员会总书记) Year Name Chinese 03/20/1943-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/07/1976-07/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 07/28/1981-01/15/1987 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 01/15/1987-07/23/1989 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 07/23/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/15/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 1 Head of State including Chairman, General Secretary, Premier and Vice Premier, President and Vice President 2 11/15/2012-Present Xi Jinping 习近平 3. Premier (中华人民共和国国务院总理) Year Name Chinese 10/1949-01/1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩来 2/2/1976-09/10/1980 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 09/10/1980-11/24/1987 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 11/24/1987-03/17/1998 Li Peng 李鹏 03/17/1998-03/16/2003 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/16/2003-03/15/2013 Wen Jiabao 温家宝 03/15/2013-Present Li Keqiang 李克强 4. Vice Premier (中华人民共和国国务院副总理) Year Name Chinese 09/15/1954-12/21/1964 Chen Yun 陈云 12/21/1964-09/13/1971 Lin Biao 林彪 09/13/1971-09/10/1980 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 09/10/1980-03/25/1988 Wan Li 万里 03/25/1988-3/05/1993 Yao Yilin 姚依林 3/25/1993-03/17/1998 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/17/1998-03/06/2003 Li Lanqing 李岚清 03/06/2003-06/02/2007 Huang Ju 黄菊 06/02/2007-03/16/2008 Wu Yi 吴仪 03/16/2008-03/16/2013 Li Keqiang 李克强 03/16/2013-Present Zhang Gaoli 张高丽 5.