Rivlin Final Formatted.Doc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Building in the Aftermath N AUGUST 29, HURRICANE KATRINA dialogue that can inform the processes by made landfall along the Gulf Coast of which professionals of all stripes will work Othe United States, and literally changed in unison to repair, restore, and, where the shape of our country. The change was not necessary, rebuild the communities and just geographical, but also economic, social, landscapes that have suffered unfathomable and emotional. As weeks have passed since destruction. the storm struck, and yet another fearsome I am sure that I speak for my hurricane, Rita, wreaked further damage colleagues in these cooperating agencies and on the same region, Americans have begun organizations when I say that we believe to come to terms with the human tragedy, good design and planning can not only lead and are now contemplating the daunting the affected region down the road to recov- question of what these events mean for the ery, but also help prevent—or at least miti- Chase W. Rynd future of communities both within the gate—similar catastrophes in the future. affected area and elsewhere. We hope to summon that legendary In the wake of the terrorist American ingenuity to overcome the physi- attacks on New York and Washington cal, political, and other hurdles that may in 2001, the National Building Museum stand in the way of meaningful recovery. initiated a series of public education pro- It seems self-evident to us that grams collectively titled Building in the the fundamental culture and urban char- Aftermath, conceived to help building and acter of New Orleans, one of the world’s design professionals, as well as the general great cities, must be preserved, revitalized, public, sort out the implications of those and protected. -

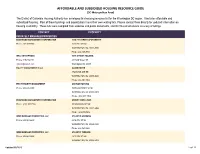

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

Washington, D.C Site Form

New York Avenue , NE Corridor, Washington, DC Florida Avenue NE & S. Dakota Avenue NE The New York Avenue NE Corridor is located northeast Any framework for this area should consider how to of Downtown. It stretches for approximately 3 miles reduce emissions and promote climate resilience between Florida Avenue NE and South Dakota Avenue while strengthening connectivity, walkability, and NE. It is a major auto-oriented gateway into the city, urban design transitions to adjacent communities and with approximately 100,000 vehicles moving through open space networks, as well as the racial and social the area every day and limited public transit options. equity conditions necessary for long-term social resilience. Robust and sustainable transportation, DC’s Mayor has set ambitious goals for more utility, and civic facility infrastructure, along with affordable housing, and development along the public amenities, are critical to unlocking the corridor could support them. The goal is to deliver as corridor’s full potential. many as 33,000 new housing units, with at least 1/3 of these being affordable. Regeneration should yield a For this site, students can choose to develop a high- vibrant residential and jobs-rich, low-carbon, mixed- level framework or masterplan for the entire site, use corridor. It should be inclusive of new affordable which may include some details on some more specific and market-rate housing units, supported by solutions, such as massing, open space and building sustainable infrastructure and community facilities. type studies. Or, students can choose to design a more detailed response for one or more of these Regeneration will need to preserve some of the subareas, (possibly working in coordinated teams so character and activity of the existing light industrial that all 3 subareas are covered):1: Union Market- (or PDR – Production, Distribution & Repair) uses. -

2017 BID Profiles

2017 DC BID PROFILES A REPORT BY THE DC BID COUNCIL 1 WISCONSIN AVE COLUMBIA RD 16TH ST 14TH ST NEW YORK AVE MASSACHUSETTS AVE M ST K ST H ST ST CAPITOL NORTH 2017 DC BID PROFILES DC BID Data .......................................................... 4 CONSTITUTION AVE DowntownDC BID ............................................... 6 Golden Triangle BID ............................................8 INDEPENDENCE AVE Georgetown BID .................................................10 Capitol Hill BID .................................................... 12 Mount Vernon Triangle CID ............................14 SOUTHEAST FRWY Adams Morgan Partnership BID ...................16 NoMa BID .............................................................. 18 Capitol Riverfront BID .....................................20 Anacostia BID ..................................................... 22 Southwest BID ....................................................24 GEORGETOWN BID DC BID Fast Facts .............................................26 ADAMS MORGAN BID S ANACOSTIA FRWY GOLDEN TRIANGLE BID DOWNTOWNDC BID MT VERNON TRIANGLE CID NOMA BID CAPITOL HILL BID SWBID N CAPITOL RIVERFRONT BID W E ANACOSTIA BID S COLLECTIVE IMPACT OF DC BIDS IN 2017 DC Business Improvement Districts invested over 30 million dollars into making the District of Columbia’s $30,877,082 high employment areas better places to live, to work and to visit. Building on a strong foundation of core clean and safe TOTAL AMOUNT BIDS INVEST IN services, BIDs work with their private and public -

Mount Vernon Triangle Historic District Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Mount Vernon Triangle Historic District other names 2. Location Bounded by 400 block Massachusetts Ave., NW on south, 400 block K St., NW on north, Prather’s Alley, NW on the east, and 5th Street (west side) on street & number the west not for publication city or town Washington, D.C. vicinity state District of Columbia code DC county code 001 zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

FY 2017 Annual Report

Mount Vernon Triangle Community Improvement District Fiscal Year 2017 Annual Report October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 twitter.com/MVTCID facebook.com/MountVernonTriangleCID instagram.com/mvtcid flickr.com youtube.com COMMUNITY IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT COMMUNITY IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT Dear Valued Stakeholders: recent headline proclaimed Mount Vernon Triangle a “Nexus Neighborhood.” Our community couldn’t agree more. More than half of the 700-plus respondents to our most recent neighborhood survey work within a one-mile radius of Mount Vernon Triangle, with 40% of respondents indicating that walking was their preferred mode of transportation to and from work. “Convenient” was the word most often cited by respondents to describe their perception of the MVT neighborhood of today. And a location- related attribute comprised four of the top six reasons why residents said they chose to live in Mount Vernon Triangle, with “Centralized location within DC” and “Proximity to work” comprising the top two most important determining factors. Clearly, “Location, Location, Location” is central to what makes #LifeinMVT so special. But as a prototypical nexus neighborhood, we recognize that the fruits of our efforts extend beyond our borders. Promoting the merits of our community’s location, convenience and livability while working to create stronger connections with surrounding neighborhoods, are all necessary and essential to the future of both Mount Vernon Triangle and downtown DC. Indeed, Mount Vernon Triangle Berk Shervin and Kenyattah Robinson sits at the epicenter of a vibrant and dynamic part of the District: • To our north is 655 New York Avenue—a project that includes multiple creative historic adaptive reuse elements—that will house The mission and vision for the Mount Vernon Triangle Advisory Board, EAB and others within 750,000+ SF of Class-A space. -

Vision Plan and Development Strategy

NoMA VISION PLAN AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY N O R T H of M A S S A C H U S E T T S A V E N U E District of Columbia Office of Planning Anthony A. Williams, Mayor OCTOBER 2006 NoMAVISION PLAN AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY A Letter from Mayor Williams Consultant Team: Acknowledgements Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, LLP Neil Kittredge, Partner-in-Charge Prepared by: Kevin Storm, Project Manager, Planner Elizabeth Pedersen, Planner District of Columbia Office of Planning Ellen McCarthy, Director Greenberg Consultants, Inc. Charles Graves, Deputy Director Neighborhood Planning, Revitalization and Design Ken Greenberg, Principal Patricia Zingsheim, Assoc. Director of Revitalization & Design, Project Manager Hamilton, Rabinovitz & Alschuler, Inc. Rosalynn Taylor, Associate Director of Neighborhood Planning John Alschuler Cindy Petkac, Ward 6 Neighborhood Planner John Meyers Deborah Crain, Ward 5 Neighborhood Planner Stephen Cochran, Zoning and Special Projects Planner, Development Review The Jair Lynch Companies Michael A. Johnson, Public/Visual Information Officer Jonathan Weinstein Shyam Kannan, Revitalization Planner Kevin Brady, Staff Assistant, Neighborhood Planning, Revitalization and Design Wells & Associates Zach Dobelbower, Capital City Fellow Marty Wells A Letter from Mayor Williams Dear Resident and Stakeholder in the District of Columbia: I am so pleased to present the NoMA Vision and Development Strategy, a plan for creating a great neighborhood. Prepared over the past year, this plan is the result of contributions by residents of Near Northeast, Eckington, Northwest One, Ivy City, Brookland, Stanton Park, Bates, Blooming- dale, Capitol Hill, as well as a number of property owners. The resulting plan is proof of the impor- tance of teamwork and citizen involvement in generating ideas and setting priorities to achieve the shared goal of making a better DC. -

Where to Find Produce Plus 2019

Where to Find Produce Plus 2019 You can get Produce Plus at any farmers’ market marked with a . You can spend Produce Plus at any market listed below. Produce Plus is a first-come, first-served program and begins on June 1st. The last day to get or spend Produce Plus will be September 29th. For more information, call the Produce Plus Hotline at (202) 888-4834 or email [email protected]. FRESHFARM Market at City SUNDAY Center DC THURSDAY Tuesdays, 11am 1098 New York Ave, NW Bloomingdale Farmers’ Arcadia’s Mobile Market Market Fort Totten Farmers’ Market Thursdays, 3pm Sundays, 9am Tuesdays, 12pm Bellevue Library 1st and R St, NW 100 Gallatin St, NE 115 Atlantic St, SW Dupont Circle New Morning Farm Stand Arcadia’s Mobile Market FRESHFARM Market Tuesdays, 3pm, Thursdays, 10am Sundays, 8:30am Sheridan School Congress Heights Senior 1500 20th St, NW 36th and Alton Pl, NW Wellness Center 3500 MLK Jr. Ave, SE Eastern Market Outdoor USDOT Farmers’ Market Farmers’ Market Tuesdays, 10am C.R.I.S.P. Market at National Sundays, 11am 3rd and M St, SE Children’s Center 225 7th St, SE Thursdays, 2pm 3400 MLK Jr. Ave, SE FRESHFARM Capitol Riverfront Farmers’ Market WEDNESDAY DC Open Air Farmers’ Market Sundays, 9am at RFK Stadium 1101 2nd St, SE Thursdays, 8am Arcadia’s Mobile Market Benning Rd & Oklahoma Ave, FRESHFARM NOMA Wednesdays, 10am NE Parking Lot No. 6 Farmers’ Market Wah Luck House Sundays, 9am 800 6th St, NW FRESHFARM Market by the 1100 1st St, NE White House Arcadia’s Mobile Market with Thursdays, 11am Common Good City Farm 810 Vermont Ave, NW Wednesdays, 3pm TUESDAY Corner of 3rd and Elm St, NW Minnesota Ave – Benning Rd Farmers’ Market Columbia Heights Thursdays, 1pm Arcadia’s Mobile Market Farmers’ Market 3924 Minnesota Ave NE Tuesdays, 3pm Wednesdays, 4pm Parkside 14th and Park Rd, NW Penn Quarter 740 Kenilworth Ave, NE FRESHFARM Market C.R.I.S.P. -

Housing in the Nation's Capital

Housing in the Nation’s2005 Capital Foreword . 2 About the Authors. 4 Acknowledgments. 4 Executive Summary . 5 Introduction. 12 Chapter 1 City Revitalization and Regional Context . 15 Chapter 2 Contrasts Across the District’s Neighborhoods . 20 Chapter 3 Homeownership Out of Reach. 29 Chapter 4 Narrowing Rental Options. 35 Chapter 5 Closing the Gap . 43 Endnotes . 53 References . 56 Appendices . 57 Prepared for the Fannie Mae Foundation by the Urban Institute Margery Austin Turner G. Thomas Kingsley Kathryn L. S. Pettit Jessica Cigna Michael Eiseman HOUSING IN THE NATION’S CAPITAL 2005 Foreword Last year’s Housing in the Nation’s Capital These trends provide cause for celebration. adopted a regional perspective to illuminate the The District stands at the center of what is housing affordability challenges confronting arguably the nation’s strongest regional econ- Washington, D.C. The report showed that the omy, and the city’s housing market is sizzling. region’s strong but geographically unbalanced But these facts mask a much more somber growth is fueling sprawl, degrading the envi- reality, one of mounting hardship and declining ronment, and — most ominously — straining opportunity for many District families. Home the capacity of working families to find homes price escalation is squeezing families — espe- they can afford. The report provided a portrait cially minority and working families — out of of a region under stress, struggling against the city’s housing market. Between 2000 and forces with the potential to do real harm to 2003, the share of minority home buyers in the the quality of life throughout the Washington District fell from 43 percent to 37 percent. -

FY 2019 Annual Report

Introduction OGETHER Mission Statement he mission and vision for the Mount Vernon TTriangle Community Improvement District is to develop Mount Vernon Triangle as a unique neighborhood within the East End of downtown Washington, DC, with a strong residential community, Class-A office space, diverse places to shop and dine, and attractive, safe and active parks and public spaces. Table of Contents 3 Leadership Message 4 Program Highlights Clean, Safe & Workforce Development Real Estate, Economic & Infrastructure Development Development Map Arts, Culture, Events & Community Building 12 What’s Next 13 Board of Directors, Staff & Clean Team Ambassadors 14 Financial Results 2 MVT CID Annual Report, 2019 Leadership Message Dear Rate Payers & Friends of Mount Vernon Triangle: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If A one-vendor farm stand on a constrained you want to go far, go together.” corner to a regionally ranked multi-vendor, ou’ll sometimes see that phrase on the Internet, in-street market that—from 2016 to 2019 social media or captured in what’s called —has grown 263% in customers, 323% in aY “meme.” Our Generation Z residents, office sales revenue and 315% in food assistance to workers, patrons and—increasingly—business vulnerable neighbors. owners use that term to describe a picture with words. A neighborhood documented for its dearth of park amenities to the future beneficiary of an In the case of the Mount Vernon Triangle additional 1.2 acres of contiguous open space. Community Improvement District, we believe the The community-led “re-activation” and phrase appropriately describes the results we “re-imagination” of Cobb Park will create achieved in our last fiscal year, accomplishments an iconic and artistic space, destination and during our last five-year renewal term, and lengths gateway into Mount Vernon Triangle and we’ve come in 15 years as one of DC’s now- downtown DC.