Arrah Like Y'know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Forest Divisions with Code

Forest Account Name of Divisions in English & Hindi with Codes Sl. Divn No. Code Name of Divisions ize.Myksa dk uke 1 SMRFOR522 Sitamarhi Forest Division, Sitamarhi lhrke<h ou izze.My ] lhrke<h 2 ARRFOR504 Araria Forest Division, Araria vjfj;k ou ize.My] vjfj;k Office of the DFO-cum- 3 WCHFOR148 dk;kZy; ou ize.My inkf/kdkjh & lg& mi funs'kd Dy.Director,V.T.P.-2, Valmikinagar, okfYefd O;k?kz vkj{k]ize.My&2 okfYefd West Champaran uxj]if'pe pEikj.k 4 SRNFOR518 Saran Forest Division, Chapra lkj.k ou ize.My]Nijk 5 NWDFOR103 Nawada Forest Division, Nawada uoknk ou ize.My]uoknk 6 PRNFOR044 Purnea Forest Division, Purnea iwf.kZ;kWa ou izze.My ]iwf.kZ;kWa 7 PTNFOR040 Patna Forest Division, Patna iVuk ou izze.My ]iVuk 8 RTSFOR071 Rohtas Forest Division, Sasaram jksgrkl ou izze.My ] jksgrkl Office of the Pr. Chief Conservator of 9 PTSFOR501 Forests, Bihar, Patna dk;kZy;]iz/kku eq[; ou laj{kd]fcgkj]iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 10 BGPFOR513 Conservator of Forests, Bhagalpur dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]Hkkxyiqj Office of the Regional Chief 11 PTNFOR038 Conservator of Forests, Patna dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd] iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 12 MUZFOR037 Conservator of Forests, Muzaffarpur dk;kZy; {ksf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]etq Q~Qjiqj Office of theWorking Plan Officer, dk;kZy; dk;Zokgd ;kstuk vf/kdkjh]ou dk; Z ;kstuk 13 PTNFOR041 Forest Working Plan Division, Patna izHkkx]iVuk 14 SPLFOR526 Supaul Forest Division, Supaul lqikSy ou ize.My]lqikSy 15 WCHFOR523 Bettiah Forest Division, Bettiah csfr;k ou izze.My ] csfr;k 16 PTSFOR530 Patna Park -

AC with District Dist

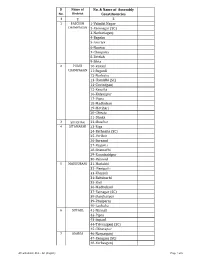

Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 1 PASCHIM 1-Valmiki Nagar CHAMPARAN 2-Ramnagar (SC) 3-Narkatiaganj 4-Bagaha 5-Lauriya 6-Nautan 7-Chanpatia 8-Bettiah 9-Sikta 2 PURVI 10-Raxaul CHAMPARAN 11-Sugauli 12-Narkatia 13-Harsidhi (SC) 14-Govindganj 15-Kesaria 16-Kalyanpur 17-Pipra 18-Madhuban 19-Motihari 20-Chiraia 21-Dhaka 3 SHEOHAR 22-Sheohar 4 SITAMARHI 23-Riga 24-Bathnaha (SC) 25-Parihar 26-Sursand 27-Bajpatti 28-Sitamarhi 29-Runnisaidpur 30-Belsand 5 MADHUBANI 31-Harlakhi 32- Benipatti 33-Khajauli 34-Babubarhi 35-Bisfi 36-Madhubani 37-Rajnagar (SC) 38-Jhanjharpur 39-Phulparas 40-Laukaha 6 SUPAUL 41-Nirmali 42-Pipra 43-Supaul 44-Triveniganj (SC) 45-Chhatapur 7 ARARIA 46-Narpatganj 47-Raniganj (SC) 48-Forbesganj AC with district Dist. - AC (English) Page 1 of 6 Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 49-Araria 50-Jokihat 51-Sikti 8 KISHANGANJ 52-Bahadurganj 53-Thakurganj 54-Kishanganj 55-Kochadhaman 9 PURNIA 56-Amour 57-Baisi 58-Kasba 59-Banmankhi (SC) 60-Rupauli 61-Dhamdaha 62-Purnia 10 KATIHAR 63-Katihar 64-Kadwa 65-Balrampur 66-Pranpur 67-Manihari (ST) 68-Barari 69-Korha (SC) 11 MADHEPURA 70-Alamnagar 71-Bihariganj 72-Singheshwar (SC) 73-Madhepura 12 SAHARSA 74-Sonbarsha (SC) 75-Saharsa 76-Simri Bakhtiarpur 77-Mahishi 13 DARBHANGA 78-Kusheshwar Asthan (SC) 79-Gaura Bauram 80-Benipur 81-Alinagar 82-Darbhanga Rural 83-Darbhanga 84-Hayaghat 85-Bahadurpur 86-Keoti 87-Jale 14 MUZAFFARPUR 88-Gaighat 89-Aurai 90-Minapur 91-Bochaha (SC) 92-Sakra (SC) 93-Kurhani 94-Muzaffarpur 95-Kanti 96-Baruraj AC with district Dist. -

Arrah Lee Gaul Collection

Arrah Lee Gaul Collection Illinois Wesleyan University Tate Archives and Special Collections July 2009 The Arrah Lee Gaul Collection The Ames Library Illinois Wesleyan University Biographical note: Arrah Lee Gaul was born in Philadelphia in 1883 as the daughter of a Methodist minister. She graduated with a degree in art from the Moore Institute of Art, Science and Industry in Philadelphia. She went on to graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania and then returned to Moore to join the faculty and become head of its art education department. She studied art in France, but is more famous for her trip to the Orient in which she spent seven years in Japan, Hong Kong, and a short while in India. She planned on visiting Egypt, but her trip was put off due to the Suez Canal incident. She spent most of her artistic life traveling, and won the honor of being the first woman artist accepted into many art competitions and art societies, including the Philadelphia Art Club and several Japanese art competitions. She is well known for her portraits and landscapes, which tended to emphasize the happier and more appealing aspects of these subjects. Upon her death in 1980, she donated 200 of her paintings to Illinois Wesleyan, a campus she had visited only once. Her father had received an honorary doctorate in theology from Illinois Wesleyan. Because of her dedication to her father, she had stipulated that these works would be donated to the university upon her death. Scope & Contents Note: This collection of documents primarily focuses on Gaul’s role as an artist, but includes some examples of her involvement with the Philadelphia Women’s Club and her religious life as well. -

Bhojpur 2019-20

Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Government of India DISTRICT PROFILE BHOJPUR 2019-20 Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Patliputra Industrial Estate, Patna-13 Phone:- 0612-2262719, 2262208, 2263211 Fax: 06121 -2262186 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedipatna.gov.in Veer Kunwar Singh Memorial, Ara, Bhojpur Sun Temple, Tarari, Bhojpur 2 FOREWORD At the instance of the Development Commissioner, Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India, New Delhi, District Industrial Profile containing basic information about the district of Bhojpur has been updated by MSME-DI, Patna under the Annual Plan 2019-20. It covers the information pertaining to the availability of resources, infrastructural support, existing status of industries, institutional support for MSMEs, etc. I am sure this District Industrial Profile would be highly beneficial for all the Stakeholders of MSMEs. It is full of academic essence and is expected to provide all kinds of relevant information about the District at a glance. This compilation aims to provide the user a comprehensive insight into the industrial scenario of the district. I would like to appreciate the relentless effort taken by Shri Ravi Kant, Assistant Director (EI) in preparing this informative District Industrial Profile right from the stage of data collection, compilation upto the final presentation. Any suggestion from the stakeholders for value addition in the report is welcome. Place: Patna Date: 31.03.2020 3 Brief Industrial Profile of Bhojpur District 1. General Characteristics of the District– Bhojpur district was carved out of erstwhile Shahbad district in 1992. The Kunwar Singh, the leader of the Mutineers during Sepoy Mutiny in 1857, was from district Bhojpur. -

Population of Class Wise Towns in Bihar

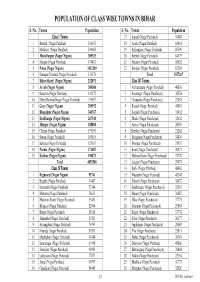

POPULATION OF CLASS WISE TOWNS IN BIHAR S. No. Towns Population S. No. Towns Population Class I Towns 17 Supaul (Nagar Parishad) 54085 1 Bettiah (Nagar Parishad) 116670 18 Araria (Nagar Parishad) 60861 2 Motihari (Nagar Parishad) 100683 19 Kishanganj (Nagar Parishad) 85590 3 Muzaffarpur (Nagar Nigam) 305525 20 Beehat (Nagar Parishad) 64579 4 Hajipur (Nagar Parishad) 119412 21 Barauni (Nagar Parishad) 58628 5 Patna (Nagar Nigam) 1432209 22 Benipur (Nagar Parishad) 62203 6 Danapur Nizamat (Nagar Parishad) 131176 Total 1557267 7 Bihar Sharif (Nagar Nigam) 232071 Class III Towns 8 Arrah (Nagar Nigam) 203380 1 Narkatiaganj (Nagar Parishad) 40830 9 Sasaram (Nagar Parishad) 131172 2 Ramnagar (Nagar Panchayat) 38554 10 Dehri DalmiyaNagar (Nagar Parishad) 119057 3 Chanpatia (Nagar Panchayat) 22038 11 Gaya (Nagar Nigam) 389192 4 Raxaul (Nagar Parishad) 41610 12 Bhagalpur (Nagar Nigam) 340767 5 Sugauli (Nagar Panchayat) 31432 13 Darbhanga (Nagar Nigam) 267348 6 Dhaka (Nagar Panchayat) 32632 14 Munger (Nagar Nigam) 188050 7 Areraj (Nagar Panchayat) 20356 15 Chapra (Nagar Parishad) 179190 8 Sheohar (Nagar Panchayat) 21262 16 Siwan (Nagar Parishad) 109919 9 Bairgania (Nagar Panchayat) 34836 17 Saharsa (Nagar Parishad) 125167 10 Motipur (Nagar Panchayat) 21957 18 Purnia (Nagar Nigam) 171687 11 Kanti (Nagar Panchayat) 20871 19 Katihar (Nagar Nigam) 190873 12 Mahnar Bazar (Nagar Panchayat) 37370 Total 4853548 13 Lalganj (Nagar Panchayat) 29873 Class II Towns 14 Barh (Nagar Parishad) 48442 1 Begusarai (Nagar Nigam) 93741 15 Masaurhi (Nagar Parishad) 45248 -

Arrah-802 301 P

IINNDDIIAANN MMEEDDIICCAALL AASSSSOOCCIIAATTIIOONN::: BBIIHHAARR SSTTAATTEE BBRRAANNCCHH LLIIISSTT OOFF LLIIIFFEE MMEEMMBBEERRSS OOFF III... MM... AA... (((AARRRRAAHH BBRRAANNCCHH))) AARRRRAAHH BBRRAANNCCHH 1. Dr. Bijoy Kumar Singh 9. Dr. Deepak Kumar BHR/1671/2/10/24417/1991-92/L BHR/1670/2/9/24416/91-92/L Kumar Sadan Club Road Mansarovar Colony, Hospital Road At & P. O. Arrah-802 301 P. O. Arrah-802 301 Dist. Bhojpur Dist. Bhojpur 2. Dr. P. B. Ojha 10. Dr. Bijoy Kumar Singh BHR/1663/2/2/24409/91-92/L BHR/1671/2/10/24417/91-92/L Retd. Civil Surgeon, Hari Jee Ka Hata Babu Bazar P. O. Arrah-802 301 P. O. Arrah-802301 Dist. Bhojpur Dist. Bhojpur 3. Dr. K. B. Sahay 11. Dr. Purushottan Singh BHR/1664/2/3/24410/91-92/L BHR/1672/2/11/24418/91-92/L Mansarovar Colony C/o Sri Ram Paras Singh Sadar Hospital Road Friend’s Colony, Katira P. O. Arrah-802 301 P. O. Arrah-802 301 Dist. Bhojpur Dist. Bhojpur 4. Dr. S. M. Isa 12. Dr. Virendra Kumar Rai BHR/1665/2/4/24411/91-92/L BHR/2727/2/25/39797/93-94/l Pakri P. O. Arrah-802 301 Medical Officer, Sadar Hospital Dist. Bhojpur P. O. Arrah-802301 Dist. Bhojpur 5. Dr. (Mrs) Jeet Sharma 13. Dr. G. D. N. Singh BHR/1666/2/5/24412/91-92/L BHR/2184/2/14/31933/93-94/L Mahavir Tola Ramna Road P. O. Arrah-802 301 P. O. Arrah-802 301 Dist. Bhojpur Dist. Bhojpur 6. Dr. S. -

B H O J P U R B U X a R Arwal Jehanabad

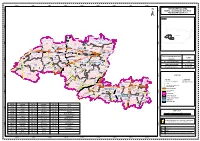

83°50'0"E 84°0'0"E 84°10'0"E 84°20'0"E 84°30'0"E 84°40'0"E 84°50'0"E 85°0'0"E 85°10'0"E N N " " 0 0 GEOGRAPHICAL AREA ' ' 0 0 ° ° 6 6 2 2 ARWAL, JEHANABAD, BHOJPUR ± AND BUXAR DISTRICTS KEY MAP N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 5 5 ° ° 5 5 2 2 B I H A R Khawaspur (Unsurveyed) ! ! Nainijor Shitab Diara Rajapur Damodarpur (Ditto) ! Rajpur Kalan ! Neyazipur ! ! Sinha ! ! ! ! Sheo Diara (Ditto) ! Gangauli Chhinegaon ! ! Babura N Keshopur Sohra ! Akauna N " ! ! Nathmalpur Barhara ! " 0 0 ' Mahuar r ! ' 0 ! e CA-17 0 4 CA-06 G iv Semaria Pararia 4 ° anga R ° 5 Kharhatanr Jawahir Diara (Ditto) ! Balua BARHARA 5 2 SIMRI ! ! Suhiya CA-15 Saraiya 2 Simri ! ! Nagpura Chandarpura ! ! ! ! ! Charkhi Deom!alpur SHAHPUR Ijri ! Gunri ! CA-07 Dumri Sarna Jhaua ! Gayghat Barsaun ! CA-18 CHAKKI ! Nimej ! Sahjauli ! Bharauli ! ! ! Semariya Palti Ojha CA-16 KOILWAR ! Arak Shahpur Chilhari Barhampur (! ARRAH ! Kathar ! Dhamar Birampur ! ! Rani Sagar ! Kaleyanpur ! Sonadia Sarimpur Bhojpur Jadid ! Belauthi ! ! ! ! (! Bhojpur Kadim ! Kant ! Ahirauli ! ! ! Giddha Noaon Kaem Nagar Koilwar Dhakaich ! Gaudar Rudar Nagar Ganghar ! (! (! ! Kari Sath ! ! Buxar.! Buxar B!aruna Á! Sasram ! SakaddÁi! Kulh!aria ! !Á Á! Bihiya ! Arrah Á! Á ! Nadaon Chhatanwar Á!Raghunathpur Osain ! Masar 922 (! ! Á ! Dumraon ! ! Á! ! (! ! £ .! ! Dhan Diha ! ! Kaithi CA-14 Á! ¤ ArrahÁ! Bhadwar Panrepatti Jagdishpur (! ! Á!Kate!a Nawada ¤£13 Sowan Á Á! !Á! ! Á! Jamira ! CA-08 BIHIYA Á Chandi Nandan ! Boksa ! Danwan Hardiya Mahdah BARHAMPUR Chakwa ! ! CA-04 ! Ariyawon ! Kaunra Gothahula ! Bimawan ! ! Khangaon Chausa BUXAR CA-05 ! ! N ! 79 ! N Total Geographical Area " ¤£ Hetampur Harigaon UdwanÁ!t Nagar " 0 DUMRAON Ekrasi ! ! 0 ' CA-09 ! ! Jogta ' 0 ! Bagen Babhniyawan ! 0 5,667 3 Á UtarwariJangalMahalJagdishpur ! CA-19 3 ° Mugaon CHOUGAIN ! Jalpura ° 5 Banarpur Itarhi ! Bhadwar ! 5 (Sq Km) 2 ! Barnaon UDWANTNAGAR 2 ! ! ! ! Sarthua Mathila ! ! CA-13 !Kasap ! ! Koran Sarai Bararhi Jagdishpur Á! ! Murar (! JAGDISHPUR Basudhar Baraon No. -

MAP of Bhojpur District

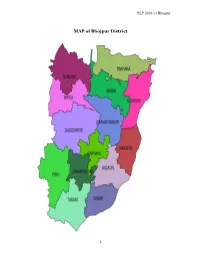

PLP 2020-21 Bhojpur MAP of Bhojpur District 4 PLP 2020-21 Bhojpur DISTRICT PROFILE District Bhojpur is agriculture based district and is located in the south west corner of Bihar. The entire district lies in the rich alluvial zone of the Ganga and its tributaries. Location and geographical area The present day Bhojpur district came into existence in 1992. The district was earlier a part of the Sahabad district. In the year 1972 Sahabad district was bifurcated in two parts namely Bhojpur and Rohtas. Buxar was a subdivision of old Bhojpur district. In 1992, Buxar became a separate district. Geographically, the district lies at 25°47'N latitude, 84°52'E longitude and 193 m Altitude. The district encompasses a geographical area of 2,395 sq km and it is bounded by Saran district and Uttar Pradesh on the North, Rohtas district on the South West, Arwal district on the South East, Patna district on the East and Buxar district on the West. The climate of the district is characterised as extremely moderate. The actual rainfall in the district was 874.3 mm, 584.3 mm and 576.6 mm during the year 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively against the average annual rainfall of 1060 mm. (Ref: http://hydro.imd.gov.in). Administration wise, the district is divided into 14 blocks namely Agiaon, Arrah, Barhara, Behea, Charpokhari, Garhani, Jagdishpur, Koilwar, Piro, Sahar, Sandesh, Shahpur, Tarari, and Udwant Nagar. Demographic profile The district has three subdivisions Ara Sadar, Jagdishpur and Piro. Ara town is the headquarters of the district and also its principal town. -

GOVERNMENT of INDIA MINISTRY of TOURISM RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.959# ANSWERED on 09.02.2021 PRIME MINISTER's SPECIAL P

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.959# ANSWERED ON 09.02.2021 PRIME MINISTER's SPECIAL PACKAGE TO BIHAR 959#. SHRI SUSHIL KUMAR MODI: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether it is a fact that Rs.600 crore have been earmarked for tourist spots in Bihar under the Prime Minister's Special Package; (b) whether it is also a fact that an amount of Rs.223.25 crore have been sanctioned for 5 schemes under the said package; (c) whether a proposal to sanction Rs. 168.75 crore for Ramayan and Buddhist circuits is pending with the Ministry of Tourism; and (d) if so, by when Government proposes to sanction the same? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) (a): Yes, Sir. Details of the tourism projects under Prime Minister’s Bihar Package are annexed. (b): Under the said package, tourism projects for a total amount of Rs.329.59 Crore have been sanctioned and an amount of Rs.241.20 Crore has been released as per details in the annexure. (c) & (d): For Buddhist Circuit under Bihar Package, two projects namely ‘Construction of Convention Centre at Bodhgaya, Bihar’ and ‘Development of Bodhgaya-Rajgir-Nalanda- Vaishali’ were identified for taking up under the Swadesh Darshan Scheme. Of this, ‘Construction of Convention Centre at Bodhgaya, Bihar’ project has been sanctioned for an amount of Rs.98.73 Crore. Sanctioning of new projects pertaining to Ramayana Circuit and Development of Bodhgaya – Rajgir – Nalanda – Vaishali under the theme of Buddhist Circuit is subject to ongoing review of the scheme. -

A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar Government of India

BIHAR ROAD SECTOR DEVELOPMENT --NEW DIMENSIONS A REPORT OF THE SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI September 2007 Bihar Road Sector Development--New Dimensions -- A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR 1. Dr. Satish C. Jha - Chairman 2. Shri Saurav Srivastava - Member 3. Late Shri Rajender Singh - Member 4. Shri R.K. Sinha - Member 5. Dr. P.V. Dehadrai - Member 6. Dr. Nachiket Mor - Member 7. Shri Tarun Das - Member 8. Shri Deepak Das Gupta - Member 9. Prof. Pradip Khandwalla - Member 10. Prof. C. P. Sinha - Member 11. Chief Secretary, Government of Bihar - Member 12. Resident Commissioner, Government of Bihar - Member Bihar Road Sector Development--New Dimensions -- A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar CONTENTS Chapter Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Preamble CHAPTER – 1 BACKGROUND CHAPTER – 2 KEY ISSUES RELATING TO ROAD SECTOR IN BIHAR CHAPTER – 3 SECTORAL STRUCTURE A. National Highways B. State Highways and Major District Roads C. Village Roads CHAPTER – 4 PUBLIC - PRIVATE DEVELOPMENT MODE CHAPTER – 5 FUTURE POLICY DIRECTION AND STRATEGIES CHAPTER – 6 CONCLUSIONS ANNEXURES Annexure 1 Annexure 2 EXHIBITS Exhibit 1 Exhibit 2 Bihar Road Sector Development--New Dimensions -- A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bihar is a landlocked state in the middle of Gangetic region with major rivers passing through it and endowing it with rich alluvial soil. It also has a rich history and cultural tradition. While Bihar has the potential of being the granary of India and a great tourist hub it suffers from pervasive poverty characterized by the poor level of infrastructure. -

Sn State District Sub-District Branch Address Pincode

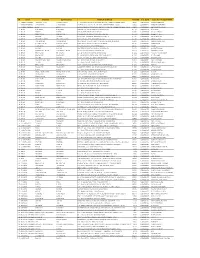

SN STATE DISTRICT SUB-DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS PINCODE IFSC CODE CONTACT PERSON NAME 1 ANDHRA PRADESH VISHAKAPATNAM VISHAKAPATNAM 47-10-20, DWARAKAPLAZA, DWARAKANAGAR, ANDHRA PRADESH-530001 530001 UCBA0000118 KAMMILA ELESWARI 2 ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA (POST BOX NO. 328),, D. NO. 27/18/47,, ANDHRA PRADESH-520002 520002 UCBA0000222 RAMISETTY SRAVANTHI 3 ANDHRA PRADESH ELURU ELURU SRI RAMA BHADRA COPLX, DNO 22B-12-10,GADEVARI, ANDHRA PRADESH-534001 534001 UCBA0000491 BHAVANIBANAVATHU 4 BIHAR BEGUSARAI BEGUSARAI MARWARI MOHALLA, MAIN ROAD, BIHAR-851101 851101 UCBA0000239 SHIKHA RAJ 5 BIHAR PURNEA PURNEA NEW MARKET, PURNEA, BIHAR-854301 854301 UCBA0000308 SURUCHI VERMA 6 BIHAR KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ GANDHI CHOWK, KISHANGANJ, BIHAR-855108 855108 UCBA0000340 SHREEKANT JHA 7 BIHAR MUNGER MUNGER PO BOX NO. 7, BEKAPUR, BEKAPUR, BIHAR-811201 811201 UCBA0000428 KULA NAND JHA 8 BIHAR KHAGARIA - BIHAR KHAGARIA - BIHAR STATION ROAD, KHAGARIA, BIHAR-851201 851201 UCBA0001494 KIRAN KUMARI 9 BIHAR GAIYARI-BIHAR GAIYARI-BIHAR VILL-GAIYARI, PO-ZERO, MILE CHOWK ARARIA,PURN, BIHAR-854311 854311 UCBA0001614 RAKESH KUMAR RAM 10 BIHAR SAHARSA - BIHAR SAHARSA - BIHAR DHRAMSHALA ROAD, SAHARSA, BIHAR-852201 852201 UCBA0001822 AMRIT KUMAR 11 BIHAR SAMASTIPUR SAMASTIPUR GOLA ROAD, SAMASTIPUR, BIHAR-848101 848101 UCBA0001926 ANKUR 12 BIHAR KATIHAR KATIHAR VINODPUR,CHUNA GALI, KATIHAR, BIHAR-854105 854105 UCBA0002255 ANURAG RAMAN 13 BIHAR MADHEPURA - BIHAR MADHEPURA - BIHAR MAIN ROAD, MADHEPURA, BIHAR-852113 852113 UCBA0002292 ANUPRIYA KUMARI 14 BIHAR BHAGALPUR -

Medical Waste Generated by Them at “Common Bio-Medical Waste Treatment Facility” Installed at Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sheikhpura, Patna

List of Health facilities availing the services pertaining to transportation, treatment & disposal of Bio- Medical Waste generated by them at “Common Bio-Medical Waste Treatment Facility” installed at Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sheikhpura, Patna. NEW REGISTRATION Registration of Firm’s After May – 2010 SI. Name & Address Contact No. Registration No. No. Allotted 1. Dr. Ajit Pradhan, 0612-2345895 CBWTF/01/2010 Jeevak Heart Hospital & Research 0612-2365814 Institute Pvt. Ltd., Fax: 0612-2363473 6-Doctor’s Colony, Kankarbagh, Patna E-mail: into@jeevak hospital.com 2. Dr. Kamal Kishore 9431422056 CBWTF/02/2010 Lab Pestisciences Intelligensio, E-mail: (Date: 14.06.2010 Vill.-Chakwara, P.o-Mazipur, Distt.- [email protected] Vaishali(Bihar) 3. Dr. Takeshwar Prasad Singh 0612-2302313 CBWTF/03/2010 Arvind Hospital Pvt. Ltd., 0612-6413672 (Date: 20.07.2010) Ashok Raj path, 0612-2300129 Patna-800004 E-mail: [email protected] 4. Dr. (Mrs.) V.Prasad, 0612-2253712 CBWTF/04/2010 Patna IV.F. @ Endo Surgery Centre, (Date: 20.07.2013) 20/B, Patliputra Colony, Patna-80000 5. Dr. (Mrs.) Kumud Kamini 0612-3362107 CBWTF/05/2010 M/S Hi-Tech Emergency Hospital,. Saguna More, Khagoul Road, Patna(Bihar) 6. Dr. Zaba Alam 9431267445 CBWTF/06/2010 M/S Alam Minorities Welfare Trust, (Date: 20.07.2013) Justica S.M.M. Alam Lane Near Mahavir Cancer Hosp. Pethiya Bazar, Phulwari Sharif Patna 7. Mr. Paras Nath Gupta, 0612-3265280 CBWTF/07/2010 M/S Modern Super Speciality (Date: 20.07.2013) Diagnostic & Research Centre, Mangal Market, Sheikhpura Patna-800014 8. Dr. Lal Path Labs Pvt.