2011 Summer Solstice Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

June 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/570 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 361 THE ETUDE -4 m UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS _OF STANDARD QUALITY__ K MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE », Alaska, Cuba, Porto Kieo, 50 WEBSTER’S NEW STANDARD 4 DICTIONARY Illustrated. NEW U. S. CENSUS In Combination with THE ETUDE money orders, bank check letter. United States postage ips^are always received for cash. Money sent gerous, and iponsible for its safe T&ke Your THE LAST WORD IN DICTIONARIES Contains DISCONTINUANCE isli the journal Choice o! the THE NEW WORDS Explicit directions Books: as well as ime of expiration, RENEWAL.—No is sent for renewals. The $2.50 Simplified Spelling, „„ ...c next issue sent you will lie printed tile date on wliicli your Webster’s Synonyms and Antonyms, subscription is paid up, which serves as a New Standard receipt for your subscription. -

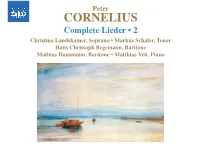

Peter CORNELIUS

Peter CORNELIUS Complete Lieder • 2 Christina Landshamer, Soprano • Markus Schäfer, Tenor Hans Christoph Begemann, Baritone Mathias Hausmann, Baritone • Matthias Veit, Piano Peter CORNELIUS (1824-1874) Complete Lieder • 2 Sechs Lieder, Op. 5 (1861-1862) 16:28 # Abendgefühl (1st version, 1862)** 2:08 1 No. 2. Auf ein schlummerndes Kind** 3:02 (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel (1813-1863)) $ Abendgefühl (2nd version, 1863)** 2:40 2 No. 3. Auf eine Unbekannte†† 5:29 (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) (Text: Christian Friedrich Hebbel) 3 No. 4. Ode* 2:34 % Sonnenuntergang (1862)† 2:29 (Text: August von Platen-Hallermünde (1796-1835)) (Text: Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843)) 4 No. 5. Unerhört† 2:45 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797-1848)) ^ Das Kind (1862)†† 0:52 5 No. 6. Auftrag* 2:38 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff) (Text: Ludwig Heinrich Christoph Hölty (1748-1776)) & Gesegnet (1862)†† 1:29 † 6 Was will die einsame Träne? (1848) 2:44 (Text: Annette von Droste-Hülshoff) (Text: Heinrich Heine (1797-1856)) * Vision (1865)** 3:30 † 7 Warum sind denn die Rosen so blaß? (c. 1862) 2:04 (Text: August von Platen-Hallermünde) (Text: Heinrich Heine) ( Die Räuberbrüder (1868-1869)† 2:43 †† Drei Sonette (1859-1861) 9:05 (Text: Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857)) (Texts: Gottfried August Bürger (1748-1794)) 8 No. 1. Der Entfernten 2:33 ) Am See (1848)† 2:37 9 No. 2. Liebe ohne Heimat 2:39 (Text: Peter Cornelius) 0 No. 3. Verlust 3:52 ¡ Im tiefsten Herzen glüht mir eine Wunde (1862)† 1:44 ! Dämmerempfindung -

284 XXVII. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Eisenach, 19. – 22. Juni 1890

284 XXVII. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Eisenach, 19. – 22. Juni 1890 1. Aufführung: Erstes Concert [auch: Erstes grosses Concert für Orchester, Soli und Chöre ] Eisenach, Stadt-Theater, Donnerstag, 19. Juni, 18:30 Uhr Ch.: verstärkter Eisenacher Musikverein Ens.: verstärkte Großhzgl. Sächs. Hofkapelle Weimar I. Teil 1. Franz Liszt: Weimars Volkslied, für Männerchor und Ltg.: Eduard Lassen Harmoniemusik Text: Peter Cornelius ( ≡) 2. Prolog Sol.: Paul Friedrich Karl Brock (Rez.) Text: Adolf Stern 3. Engelbert Humperdinck: Das Glück von Edenhall, Ballade Ltg.: Engelbert Humperdinck für Chor und Orchester (EA) Text: Ludwig Uhland ( ≡) 4. Felix Draeseke: Symphonisches Vorspiel zu Heinrich von Ltg.: Richard Strauss Kleists Tragödie Penthesilea 5. Franz Schubert: Ltg.: Hermann Thureau a) „Tantum ergo“, für Soli, Chor und Orchester (Ms., ≡ Sol.: Hedwig Kühn, Auguste Phister, Heinrich lat. und dt.) Zeller, Rudolf von Milde b) Offertorium, für Tenorsolo, Chor und Orchester (Ms., ≡ lat. und dt.) 6. Pëtr Il’i č, Čajkovskij: Serenade für Streichorchester C-Dur Ltg.: Richard Strauss op. 48 Elegie und Finale 7. Johannes Brahms: Schicksalslied, für Chor und Orchester Ltg.: Hermann Thureau Text: Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (≡) II. Teil 8. Franz Liszt: Chöre zu Der entfesselte Prometheus Ltg.: Eduard Lassen Text: Johann Gottfried Herder, verbindende Dichtung: Sol.: Hedwig Kühn, Auguste Phister, Hans Richard Pohl ( ≡) Gießen, Heinrich Zeller, Rudolf von Milde, Ernst Hungar, Paul Friedrich Karl Brock (Rez.) 2. Aufführung: Zweites Concert (Kammermusik-Aufführung) Eisenach, Clemda, Saal, Freitag, 20. Juni, 11:00 Uhr Konzertflügel: Carl Bechstein, Berlin 1. Robert Kahn: Quartett für 2 Violinen, Viola und Sol.: Karl Halir (V.), Theodor Freiberg (V.), Violoncell A-Dur op. 8 Karl Nagel (Va.), Leopold Grützmacher (Vc.) 1. -

![103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5324/103-musikertag-magdeburg-15-16-18-september-1871-2505324.webp)

103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871

103 Musikertag Magdeburg, 15. [16.] – 18. September 1871 1. Aufführung: Großes Concert für Instrumental- und Vocal-Vorträge, veranstaltet vom Allgemeinen deutschen Musikverein Magdeburg, Johanniskirche, Samstag, 16. September, 18:30 – nach 21:00 Uhr Ltg.: Gustav Rebling Org.: Sauer, Frankfurt (Oder) 1. August Gottfried Ritter: Freier Vortrag auf der Orgel Sol.: August Gottfried Ritter (Org.) 2. Hermann Zopff: Religiöse Gesänge für Tenor, Orgel, Sol.: Johannes Müller (T), Brand (Org.), Bohne Violine und Viola (a) V.), Heinrich Klesse (a) Va.) a) Pfingstgruss Text: Luise Otto (≡) b) In stillen Stunden Text: Moritz Alexander Zille (≡) 3. Gustav Rebling: Der 12. Psalm für 8stimmigen Chor a Ch.: Reblingscher Kirchengesangverein capella op. 13 Nr. 1 ( ≡ dt.) 4. Hans Bronsart von Schellendorff: Fantasiestück für Sol.: Robert Heckmann (V.), Brand (Org.) Violine und Orgel 5. Peter Cornelius: „Von dem Dome schwer und bang“, Ch.: Magdeburger Liedertafel II Trauerchor für Männerstimmen Text: Friedrich von Schiller, aus Die Glocke ( ≡) ---- 6. Gustav Adolf Merkel: Adagio für Violoncello und Orgel Sol.: Leopold Grützmacher (Vc.), Rudolf Palme (Org.) 7. Eduard Lassen: Palmblätter, für Solostimmen und Sol.: Anna Worgitzka (S), Bertha Dotter (A), Begleitung Johannes Müller (T), Leopold Müller (B), Text: Karl Gerok Robert Ravenstein (a) B), Rudolf Palme (Org.), 2 Gesänge ( ≡) Müller (Hr.), Adolf Hankel (Hf.) a) Bethanien, für Sopran, Alt, Tenor, 2 Bässe und Orgel- Begleitung b) In Joseph’s Garten, für Alt, Tenor und Bass-Solo mit Begleitung von Orgel, Horn und Harfe 8. Friedrich Kiel: Fantasie für Orgel h-Moll op. 58 Nr. 2 Sol.: Gustav Rebling (Org.) 1. Maestoso 2. Recitativo 3. Tema con Variazione ---- 9. Franz Liszt: Missa choralis, für Chor, Solostimmen und Sol.: Anna Worgitzka (S), Bertha Dotter (A), Orgel ( ≡ lat. -

The Story of an Operetta

Vorträge und Abhandlungen zur Slavistik ∙ Band 15 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Nicholas G. Zekulin The Story of an Operetta Le dernier sorcier by Pauline Viardot and Ivan Turgenev Vol. 1 Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbHNicholas. G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-428-5 © by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1989. Abteilung der Firma Kubon und Sagner, Buchexport/import GmbH München Offsetdruck: Kurt Urlaub, Bamberg Nicholas G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access 00047504 Vorträge und Abhandlungen zur Slavistik• i • herausgegeben von Peter Thiergen (Bamberg) Band 15 1989 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER * MÜNCHEN Nicholas G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access Nicholas G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access THE STORY OF AN OPERETTA LE DERNIER SORCIER BY PAULINE VIARDOT AND IVAN TURGENEV von Nicholas G. Žekulin Nicholas G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access PART I BADINERIES IN BADEN-BADEN Nicholas G. Žekulin - 9783954794058 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:51:33AM via free access 00047504 For Marian, with whom so many of my musical experiences are associated. -

Topy Nguyen, Trombone Taiko Pelick, Piano

Presents Topy Nguyen, trombone Taiko Pelick, piano Thursday, October 29th, 2020 8:30 PM Program Concert pour Trombone et Piano ou Orchestre (1924) Launy Grøndahl I. Moderato assai ma molto maestoso (1886-1960) II. Quasi una Leggenda: Andante grave III. Finale: Maestoso - Rondo Intermission Zwei Fantasiestücke, “Two Fantasy Pieces” Op. 48 (1873) Eduard Lassen I. Andacht (Devotion) (1830-1904) II. Abendreigen (Evening Round Dance) ed. Blair Bollinger Cavatine, Op. 144 (1915) Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) This recital is given in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Music Education in Instrumental Concentration. Mr. Nguyen is a student of Dr. David Begnoche. Concert pour Trombone et Piano ou Orchestre (1924) Launy Grøndahl Launy Grøndahl started his professional career at the age of thirteen when he was assigned his first work as a violinist with the Orchestra of the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen. Following in the footsteps of Denmark’s most prominent composer, Carl Nielson, Grøndahl started his work as both a conductor and a composer, becoming the resident conductor of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra as well as writing symphonies, chamber music, and concertos. Written while Grøndahl was spending time in Italy, his trombone concerto has been regarded as one of his best known works and has also cemented itself as one of the major works for the instrument. The first movement starts prominently with this piece’s famous motif that maintains a strict rhythmic structure before transitioning to more fluid and rubato ideas, a musical juxtaposition that will appear frequently throughout the entire concerto. The second movement continues this idea of juxtaposition as it alternates between a darker, less stable andante grave section and a calmer, more delicate mosso section, before surprising the listeners with a dramatic and emotional ad lib figure. -

Brass Instruments

Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 5/18/2011 BRASS INSTRUMENTS CD 122 Edward Tarr, trumpet/Elisabeth Westenholz, piano/organ Rhapsody in Blue (George Gershwin) Sonatina for trumpet and piano (Bohuslav Martinu) Sonatina for trumpet and piano (Carl Alexius) Sonata (Paul Hindemith) Thème et variations sur le Psaume 149 du Psautier de la Réforme, Chantez à Dieu chanson nouvelle for trumpet and organ (Alexandre Cellier) Duo for trumpet and organ, Op. 53 (Fritz Werner) Phantasy No. 1 for trumpet and organ, Op. 57 (Stanley Weiner) CD 128 The Virtuoso Trombone Christian Lindberg, trombone/Roland Pöntinen, piano The Flight of the Bumble-Bee (Nikolaj Rimskij-Korsakov) Sonata (vox Gabrieli) for trombone and piano (Stjepan Sulek) Ballade pour trombone et piano (Frank Martin) Csárdas (Vittorio Monti) Liebesleid (Fritz Kreisler) Blue Bells of Scotland (Arthur Pryor) Sonata für Posaune und Klavier (Paul Hindemith) Sequenza V for trombone solo (Luciano Berio) CD 133 The Romantic Trombone Christian Lindberg, trombone Roland Pöntinen, piano Piece in e flat minor (J. Guy Ropartz) Salve Maria (Saverio Mercadante) Cavatine, Op. 144 (Camille Saint-Saëns) Morceau symphonique (Philippe Gaubert) Aria et Polonaise, Op. 128 (Joseph Jongen) Fantaisie (Sigismond Stojowski) Vallflickans dans (Hugo Alfvén) Romance (Carl Maria von Weber) CD 158 l’adagio d’ Albinoni Maurice André, trumpet Concerto de Varsovie (R. Addinsell) La Cavatine du Barbier de Seville (G. Rossini) Serenade (F. Schubert) Ave Maria (F. Schubert) Danse bongroise No. 5 (J. Brahms) Largo (Haendel) Concerto pour deux trompettes, 1st movement (A. Vivaldi) Ave Maria (C. Gounod) Danse bongroise No. 6 (J. Brahms) Gloria in excelsis deo (Haendel) Danse rituelle du feu (M. -

Honor's Recital 2021

St. Norbert College Music Department Presents Honor’s Recital Featuring: Marquise Weatherall, percussion Emily Martin, voice Kassidy Freund, trombone Anna VanSeveren, piano Brice Tepsa, trumpet Katie Coyle, voice Jonathan Tesch, oboe Nate Perttu, trombone Emma Kindness, voice Accompanists: Mrs. Elaine Moss Mr. Connor Klavekoske Tuesday, May 4th, 2021 St. Norbert College Dudley Birder Hall 7:30 p.m. ~ Program ~ Tork………………………..……………...……………James Campbell Marquise Weatherall, percussion Willow Song from The Ballad of Baby Doe…………….Douglas Moore Emily Martin, voice Zwei Fantasiestuck………………………………………..Eduard Lassen arr. Blair Bollinger Kassidy Freund, trombone Nocturne………………………………………..………..Claude Debussy Anna VanSeveren, piano Concert Etude…………………………………..…...Alexander Goedicke Brice Tepsa, trumpet Gretchen Am Spinnrade……………………………….... Franz Schubert Katie Coyle, voice A Million Numbered Streets from Nine New York City Miniatures Gary Powell Nash Jonathan Tesch, oboe Concertino………………………….…………...……Lars-Erik Larsson II. Aria; Andante Sostenuto III. Finale; Allegro Giocoso Nate Perttu, trombone Monica's Waltz from The Medium…………………Gian Carlo Menotti Emma Kindness, voice ~ Biographies ~ Marquise Weatherall is a junior from Madison, WI and he is a Music Performance Major at St. Norbert College. Marquise is currently studying Percussion in the studio of Jim Robl. Marquise is involved in Wind Ensemble, Jazz Ensemble, Bell Choir and Concert Band. In Concert Band, he plays the Blue Trombone. Outside of his Music Major classes and ensembles, he is involved in many different things on campus! He is the Vice President of SNC Klezmer Ensemble, Secretary of SNC Acafellas, Social Media Chair for Black Student Union, a Program Assistant at the Cassandra Voss Center, SNC Tour Guide, and is a part of the National Association for Music Educators and Knight Theatre. -

Richard Strauss: the Don Juan Recordings Raymond Holden

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 3 Number 1 Spring Richard Strauss: the Don Juan Recordings Raymond Holden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Holden, Raymond (1997) "Richard Strauss: the Don Juan Recordings," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Background career as a conductor, 1884-1949, Don Juan (composed 1888)l continued to be of some importance to him. gularly at his subscription concerts and at the performances that directed as a guest conductor. From the outset, it was clear that t tone poem was conceived for a virtuoso orchestra. At the premier conducted by Strauss, the provincial Weimar orchestra was tested its limits. In a letter to his parents, dated 8 N his impressions of the first rehearsal: sterday, I directed the first (part proof-reading) on Juan." . even though it is terribly difficul nded splendid and came across magni Whilst it has been argued that Don Juan w 1888, Strauss stated that he "invented" the initial themes during a visit to the mo- 12 Raymond Holden sorry for the poor horns and trumpets. They blew them- selves completely blue . it's fortunate that the piece is short. -

Autographs, Prints, & Memorabilia from the Collection of Marilyn Horne

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Autographs, Prints, & Memorabilia From the Collection of Marilyn Horne 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA Telephone 516-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to insure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. v Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com Fine Items & Collections Purchased v Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

A Thousand Nineteenth-Century Belgian Songs

A Thousand Nineteenth-Century Belgian Songs Barbara Mergelsberg Since Belgium’s independence from the Netherlands in 1830, vocal music has played an important role in the country’s cultural life. Belgium’s original art song repertoire, whose style can be seen as linking German lied and French mélodie , rarely appears on concert programs. The following concise overview aims to revisit Belgium’s neglected nineteenth century art song heritage of over a thousand songs. Along the way, it provides some historical and cultural information about Belgium, as well as musical examples and practical information for performers. The essay consists of two parts. The first part discusses chosen works of a few prominent composers of the early generation born before 1840. The second part looks at selected composers of the second generation born between 1840 and 1870. Composers of the First Generation César Franck (1822-1890) • Adolphe Samuel (1824-1898) • Eduard Lassen (1830-1904) Peter Benoit (1834-1901) • Jean-Théodore Radoux (1835-1911) When César Franck and Adolphe Samuel were born, Belgium was under Dutch rule and did not yet exist as a sovereign country. It only earned its independence in 1830, shortly before Franck entered the Royal Conservatory of Liège. Belgium’s official language in the nineteenth century was French. The Flemish language spoken in the north was discarded as the language of the peasants and the poor, which, unsurprisingly, triggered a strong Flemish national movement against this unjust situation. Belgium’s ethnic mixture and its linguistic tensions were present from its very beginnings. The country’s territory at that time did not yet encompass the German-speaking community.