Fraud on the Court and Abusive Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting the Innocent from False Confessions and Lost Confessions--And from Miranda Paul G

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 88 Article 2 Issue 2 Winter Winter 1998 Protecting the Innocent from False Confessions and Lost Confessions--And from Miranda Paul G. Cassell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Paul G. Cassell, Protecting the Innocent from False Confessions and Lost Confessions--And from Miranda, 88 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 497 (Winter 1998) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/98/8802-0497 TI' JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW& CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 88, No. 2 Copyright 0 1998 by Northwestern Unh-rsity, School of Law PrinW in U.S.A PROTECTING THE INNOCENT FROM FALSE CONFESSIONS AND LOST CONFESSIONS-AND FROM MIRANDA PAUL G. CASSELL" For most of the last several decades, criminal procedure scholarship-mirroring the Warren Court landmarks it was commenting on-spent little time discussing the guiltless and much discussing the guilty. Recent scholarship suggests a dif- ferent focus is desirable. As one leading scholar recently put it, "the Constitution seeks to protect the innocent."' Professors Leo and Ofshe's preceding article,2 along with ar- ticles like it by (among others) Welsh White and Al Alschuler,4 commendably adopts this approach. Focusing on the plight of an innocent person who confessed to a crime he5 did not com- mit, they recommend certain changes in the rules governing po- " Professor of Law, University of Utah College of Law ([email protected]). -

Human Trafficking and Exploitation

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EXPLOITATION MANUAL FOR TEACHERS Third Edition Recommended by the order of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Armenia as a supplemental material for teachers of secondary educational institutions Authors: Silva Petrosyan, Heghine Khachatryan, Ruzanna Muradyan, Serob Khachatryan, Koryun Nahapetyan Updated by Nune Asatryan The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication has been issued without formal language editing by IOM. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Armenia 14, Petros Adamyan Str. UN House, Yerevan 0010, Armenia Telephone: ¥+374 10¤ 58 56 92, 58 37 86 Facsimile: ¥+374 10¤ 54 33 65 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.iom.int/countries/armenia © 2016 International Organization for Migration ¥IOM¤ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

The Lawyer As an Officer of the Court--His Duty to the Court in the Administration of Justice Isaac M

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 4 | Number 3 Article 1 1926 The Lawyer As an Officer of the Court--His Duty to the Court in the Administration of Justice Isaac M. Meekins Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Isaac M. Meekins, The Lawyer As an Officer ofh t e Court--His Duty to the Court in the Administration of Justice, 4 N.C. L. Rev. 95 (1926). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol4/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. North Carolina Law Review Volume Four June, 1926 Number Three THE LAWYER AS AN OFFICER OF THE COURT -HIS DUTY TO THE COURT IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE* ISAAC M. MEEKINS JUDGE OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT My first duty this evening is personal. I hasten to perform that duty by saying frankly that I deeply appreciate the consideration involved in your invitation to address you. I consider the oppor- tunity a distinct honor, and I find it difficult to convey the full measure of my value of your confidence and esteem. When I began to reflect upon the subject you assigned me: "The Lawyer as an Officer of the Court-His Duty to the Court in the Administration of Justice," involuntarily my memory ran. -

Proffer, Plea and Cooperation Agreements in the Second Circuit

G THE B IN EN V C R H E S A N 8 D 8 B 8 A E 1 R SINC Web address: http://www.law.com/ny VOLUME 230—NO.27 THURSDAY, AUGUST 7, 2003 OUTSIDE COUNSEL BY ALAN VINEGRAD Proffer, Plea and Cooperation Agreements in the Second Circuit he Department of Justice over- Northern and Western districts provide sees 93 U.S. Attorney’s offices that proffer statements will not be used in throughout the country and any criminal proceeding, the Eastern and beyond. Thousands of criminal Southern agreements are narrower, T promising only that such statements will prosecutors in these offices are responsible for enforcing a uniform set of criminal not be introduced in the government’s statutes, sentencing guidelines and case-in-chief or at sentencing. Thus, Department of Justice internal policies. proffer statements in those districts may Among the basic documents that are be offered at detention hearings and criminal prosecutors’ tools of the trade are suppression hearings as well as grand proffer, plea and cooperation agreements. jury proceedings. These documents govern the relationship Death Penalty Proffer. The Eastern between law enforcement and many of the District’s proffer agreement has a provision subjects, targets and defendants whom defendant) to make statements to the that assures a witness or defendant that DOJ investigates and prosecutes. government without fear that those proffer statements will not be considered Any belief that these agreements are as statements will be used directly against the by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in deciding uniform as the laws and policies underly- witness in a later prosecution. -

The Lawyer As Officer of the Court

THE LAW1VYER AS OFFICER OF COURT THE LAWYER AS AN OFFICER OF THE COURT. T HE lawyer is both theoretically and actually an officer of the court. This has been recognized in principle throughout the history of the profession. In ancient Rome the advocatms, when called upon by the prctor to assist in the cause of a client, was solemnly admonished "to avoid artifice and circumlocu- tion." 1 The principle was recognized also among practically all of the European nations of the Middle Ages. In 1221 Frederick the Second, of Germany, prescribed the following oath for advo- cates : 2 "We will that the advocates to be appointed, as well in our court as before the justices and bailiffs of the provinces, be- fore entering upon their offices, shall take their corporal oath on the Gospels, that the parties whose cause they have undertaken they will, with all good faith and truth, with- out any tergiversation, succour; nor will they allege anything against their sound conscience: nor will they undertake des- perate causes: and, should they have been induced, by mis- representation and the colouring of the party to undertake a cause which, in the progress of the suit, shall appear to them, in fact or law, unjust, they will forthwith abandon it. Liberty is not to be granted to the abandoned party to have recourse to another advocate. They shall also swear that, in the progress of the .suit, they will not require an addi- tional fee. nor on the part of the suit enter into any com- pact; which oath it shall not be sufficient for them to swear to once only, but they shall renew it every year before the offi- cer of justice. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

Description of Bite Mark Exonerations

DESCRIPTION OF BITE MARK EXONERATIONS 1. Keith Allen Harward: Keith Harward was convicted of the September 1982 murder of a man and the rape of his wife. The assailant, who was dressed as a sailor, bit the rape victim’s legs multiple times during the commission of the rape. Because of the assailant’s uniform, the investigation focused on the sailors aboard a Navy ship dry-docked near the victims’ Newport News, Virginia, home. Dentists aboard the ship ran visual screens of the dental records and teeth of between 1,000 and 3,000 officers aboard the ship; though Harward’s dentition was initially highlighted for additional screening, a forensic dentist later excluded Harward as the source of the bites. The crime went unsolved for six months, until detectives were notified that Harward was accused of biting his then-girlfriend in a dispute. The Commonwealth then re-submitted wax impressions and dental molds of Harward's dentition to two ABFO board-certified Diplomates, Drs. Lowell Levine and Alvin Kagey, who both concluded that Harward was the source of bite marks on the rape victim. Although the naval and local dentists who conducted the initial screenings had excluded Harward as the source of the bites, in the wake of the ABFO Diplomates’ identifications they both changed their opinions. Harward’s defense attorneys also sought opinions from two additional forensic dentists prior to his trials, but those experts also concluded that Harward inflicted the bites; in total, six forensic dentists falsely identified Harward as the biter. At Harward's second trial, Dr. -

The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation

LENS FINAL 12/1/2010 5:47:02 PM Honest Confusion: The Purpose of Compensatory Damages in Tort and Fraudulent Misrepresentation Jill Wieber Lens∗ I. INTRODUCTION Suppose that a plaintiff is injured in a rear-end collision car accident. Even though the rear-end collision was not a dramatic accident, the plaintiff incurred extensive medical expenses because of a preexisting medical condition. Through a negligence claim, the plaintiff can recover compensatory damages based on his medical expenses. But is it fair that the defendant should be liable for all of the damages? It is not as if he rear-ended the plaintiff on purpose. Maybe the fact that defendant’s conduct was not reprehensible should reduce the amount of damages that the plaintiff recovers. Any first-year torts student knows that the defendant’s argument will not succeed. The defendant’s conduct does not control the amount of the plaintiff’s compensatory damages. The damages are based on the plaintiff’s injury because, in tort law, the purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole by putting him in the same position as if the tort had not occurred.1 But there are tort claims where the amount of compensatory damages is not always based on the plaintiff’s injury. Suppose that a defendant fraudulently misrepresents that a car for sale is brand-new. The plaintiff then offers to purchase the car for $10,000. Had the car actually been new, it would have been worth $15,000, but the car was instead worth only $10,000. As they have for a very long time, the majority of jurisdictions would award the plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages 2 based on the plaintiff’s expected benefit of the bargain. -

The Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance Exceptions

Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentences: The Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance Exceptions Updated February 22, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41326 SUMMARY R41326 Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentences: February 22, 2019 The Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance Charles Doyle Exceptions Senior Specialist in American Public Law Federal law requires a sentencing judge to impose a minimum sentence of imprisonment following conviction for any of a number of federal offenses. Congress has created three exceptions. Two are available in any case where the prosecutor asserts that the defendant has provided substantial assistance in the criminal investigation or prosecution of another. The other, commonly referred to as the safety valve, is available, without the government’s approval, for a handful of the more commonly prosecuted drug trafficking and unlawful possession offenses that carry minimum sentences. Qualification for the substantial assistance exceptions is ordinarily only possible upon the motion of the government. In rare cases, the court may compel the government to file such a motion when the defendant can establish that the refusal to do so was based on constitutionally invalid considerations, or was in derogation of a plea bargain obligation or was the product of bad faith. Qualification for the safety valve exception requires a defendant to satisfy five criteria. His past criminal record must be minimal; he must not have been a leader, organizer, or supervisor in the commission of the offense; he must not have used violence in the commission of the offense, and the offense must not have resulted in serious injury; and prior to sentencing, he must tell the government all that he knows of the offense and any related misconduct. -

In (Partial) Defense of Strict Liability in Contract

Michigan Law Review Volume 107 Issue 8 2009 In (Partial) Defense of Strict Liability in Contract Robert E. Scott Columbia University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Contracts Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Robert E. Scott, In (Partial) Defense of Strict Liability in Contract, 107 MICH. L. REV. 1381 (2009). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol107/iss8/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN (PARTIAL) DEFENSE OF STRICT LIABILITY IN CONTRACT Robert E. Scott* Many scholars believe that notions of fault should and do pervade contract doctrine. Notwithstanding the normative and positive ar- guments in favor of a fault-based analysis of particular contract doctrines, I argue that contract liability is strict liability at its core. This core regime is based on two key prongs: (1) the promisor is li- able to the promisee for breach, and that liability is unaffected by the promisor'sexercise of due care orfailure to take efficient precau- tions; and (2) the promisor's liability is unaffected by the fact that the promisee, prior to the breach, has failed to take cost-effective precau- tions to reduce the consequences of nonperformance. I offer two complementary normative justificationsfor contract law's stubborn resistance to considerfault in either of these instances. -

From False Evidence Ploy to False Guilty Plea: an Unjustified Path to Securing Convictions Introduction

COMMENT From False Evidence Ploy to False Guilty Plea: An Unjustified Path to Securing Convictions introduction On June 20, 1991, two police officers brought an African American man named Anthony Gray into custody for questioning related to the unsolved rape and murder of a woman in Calvert County, Maryland.1 During the interroga- tion, the detectives lied to Mr. Gray about the evidence police held against him. They told him that two other men had confessed to involvement in the crime and had named Mr. Gray as the killer.2 They told him that he had failed two hour-long polygraph tests.3 And they told him that they “knew” he had com- mitted the crime.4 In reality, no one had confessed to the crime or identified Anthony Gray as the perpetrator.5 Mr. Gray did not fail the polygraph tests.6 Instead, the police had gathered “a substantial amount of exculpating evidence” during the period of time when Mr. Gray was being interrogated.7 Witnesses reported having seen a lone white man driving from the crime scene in the victim’s car, and the hair evidence that police recovered could have only come from a Caucasian 1. Gray v. Maryland, No. CIV.CCB-02-0385, 2004 WL 2191705, at *2 (D. Md. Sept. 24, 2004). This account of Anthony Gray’s case is based on judicial opinions that present the factual record in the light most favorable to the defendant. 2. Gray v. Maryland, 228 F. Supp. 2d 628, 632 (D. Md. 2002). 3. Gray, 2004 WL 2191705, at *3. -

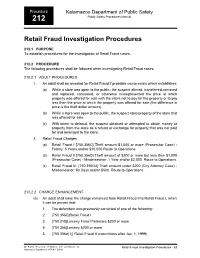

Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures

Procedure Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety Public Safety Procedures Manual 212 Retail Fraud Investigation Procedures 212.1 PURPOSE To establish procedures for the investigation of Retail Fraud cases. 212.2 PROCEDURE The following procedures shall be followed when investigating Retail Fraud cases. 212.2.1 ADULT PROCEDURES 1. An adult shall be arrested for Retail Fraud if probable cause exists which establishes: (a) While a store was open to the public, the suspect altered, transferred, removed and replaced, concealed, or otherwise misrepresented the price at which property was offered for sale with the intent not to pay for the property or to pay less than the price at which the property was offered for sale (the difference in price is the theft dollar amount). (b) While a store was open to the public, the suspect stole property of the store that was offered for sale. (c) With intent to defraud, the suspect obtained or attempted to obtain money or property from the store as a refund or exchange for property that was not paid for and belonged to the store. 2. Retail Fraud Charges (a) Retail Fraud I [750.356C] Theft amount $1,000 or more (Prosecutor Case) - Felony: 5 Years and/or $10,000 Route to Operations. (b) Retail Fraud II [750.356D] Theft amount of $200 or more but less than $1,000 (Prosecutor Case) - Misdemeanor: 1 Year and/or $2,000. Route to Operations. (c) Retail Fraud III- [750.356D4] Theft amount under $200 (City Attorney Case) - Misdemeanor: 93 Days and/or $500. Route to Operations 212.2.2 CHARGE ENHANCEMENT (a) An adult shall have the charge enhanced from Retail Fraud II to Retail Fraud I, when it can be proven that: 1.