Study of Vaqarr Comuna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Datë 06.03.2021

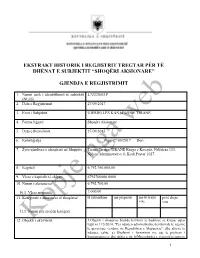

EKSTRAKT HISTORIK I REGJISTRIT TREGTAR PËR TË DHËNAT E SUBJEKTIT “SHOQËRI AKSIONARE” GJENDJA E REGJISTRIMIT 1. Numri unik i identifikimit të subjektit L72320033P (NUIS) 2. Data e Regjistrimit 27/09/2017 3. Emri i Subjektit UJËSJELLËS KANALIZIME TIRANË 4. Forma ligjore Shoqëri Aksionare 5. Data e themelimit 27/09/2017 6. Kohëzgjatja Nga: 27/09/2017 Deri: 7. Zyra qëndrore e shoqërisë në Shqipëri Tirane Tirane TIRANE Rruga e Kavajës, Ndërtesa 133, Njësia Administrative 6, Kodi Postar 1027 8. Kapitali 6.792.760.000,00 9. Vlera e kapitalit të shlyer: 6792760000.0000 10. Numri i aksioneve: 6.792.760,00 10.1 Vlera nominale: 1.000,00 11. Kategoritë e aksioneve të shoqërisë të zakonshme me përparësi me të drejte pa të drejte vote vote 11.1 Numri për secilën kategori 12. Objekti i aktivitetit: 1.Objekti i shoqerise brenda territorit te bashkise se krijuar sipas ligjit nr.l 15/2014, "Per ndarjen administrative-territoriale te njesive te qeverisjes vendore ne Republiken e Shqiperise", dhe akteve te ndarjes, eshte: a) Sherbimi i furnizimit me uje te pijshem i konsumatoreve dhe shitja e tij; b)Mirembajtja e sistemit/sistemeve 1 te furnizimit me ujë te pijshem si dhe të impianteve te pastrimit te tyre; c)Prodhimi dhe/ose blerja e ujit per plotesimin e kerkeses se konsumatoreve; c)Shërbimi i grumbullimit, largimit dhe trajtimit te ujerave te ndotura; d)Mirembajtja e sistemeve te ujerave te ndotura, si dhe të impianteve të pastrimit të tyre. 2.Shoqeria duhet të realizojë çdo lloj operacioni financiar apo tregtar që lidhet direkt apo indirect me objektin e saj, brenda kufijve tè parashikuar nga legjislacioni në fuqi. -

Response of the Albanian Government

CPT/Inf (2006) 25 Response of the Albanian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Albania from 23 May to 3 June 2005 The Albanian Government has requested the publication of this response. The report of the CPT on its May/June 2005 visit to Albania is set out in document CPT/Inf (2006) 24. Strasbourg, 12 July 2006 Response of the Albanian Government to the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on its visit to Albania from 23 May to 3 June 2005 - 5 - REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Legal Representative Office No.______ Tirana, on 20.03.2006 Subject: The Albanian Authority’s Responses on the Report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and other Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (CPT) The Committee for the Prevention of Torture and other Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (CPT) Mrs. Silvia CASALE - President Council of Europe - Strasbourg Dear Madam, Referring to your letter date 21 December 2005 in the report of 2005 of CPT for Albania, we inform that our state authorities are thoroughly engaged to realize the demands and recommendations made by the CPT and express their readiness to cooperate for the implementation and to take the concrete measures for the resolution of the evidenced problems in this report. Responding to your request for information as regards to the implementation of the submitted recommendations provided in the paragraphs 68, 70, 98, 131, 156 of the report within three months deadline, we inform that we have taken a response form the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Health meanwhile the Ministry of interior will give a response as soon as possible. -

GTZ-Regional Sustainable Development Tirana 2002

GTZ GmbH German Technical Cooperation, Eschborn Institute of Ecological and Regional Development (IOER), Dresden Towards a Sustainable Development of the Tirana – Durres Region Regional Development Study for the Tirana – Durres Region: Development Concept (Final Draft) Tirana, February 2002 Regional Development Study Tirana – Durres: Development Concept 1 Members of the Arqile Berxholli, Academy of Sci- Stavri Lami, Hydrology Research Working Group ence Center and authors of Vladimir Bezhani, Ministry of Public Perparim Laze, Soil Research In- studies Works stitute Salvator Bushati, Academy of Sci- Fioreta Luli, Real Estate Registra- ence tion Project Kol Cara, Soil Research Institute Irena Lumi, Institute of Statistics Gani Deliu, Tirana Regional Envi- Kujtim Onuzi, Institute of Geology ronmental Agency Arben Pambuku, Civil Geology Ali Dedej, Transport Studies Insti- Center tute Veli Puka, Hydrology Research Llazar Dimo, Institute of Geology Center Ilmi Gjeci, Chairman of Maminas Ilir Rrembeci, Regional Develop- Commune ment Agency Fran Gjini, Mayor of Kamza Mu- Thoma Rusha, Ministry of Eco- nicipality, nomic Cooperation and Trade Farudin Gjondeda, Land and Wa- Skender Sala, Center of Geo- ter Institute graphical Studies Elena Glozheni, Ministry of Public Virgjil Sallabanda, Transport Works Foundation Naim Karaj, Chairman of National Agim Selenica, Hydro- Commune Association Meteorological Institute Koco Katundi, Hydraulic Research Agron Sula , Adviser of the Com- Center mune Association Siasi Kociu, Seismological Institute Mirela Sula, -

Albania: Average Precipitation for December

MA016_A1 Kelmend Margegaj Topojë Shkrel TRO PO JË S Shalë Bujan Bajram Curri Llugaj MA LËSI Lekbibaj Kastrat E MA DH E KU KË S Bytyç Fierzë Golaj Pult Koplik Qendër Fierzë Shosh S HK O D Ë R HAS Krumë Inland Gruemirë Water SHK OD RË S Iballë Body Postribë Blerim Temal Fajza PUK ËS Gjinaj Shllak Rrethina Terthorë Qelëz Malzi Fushë Arrëz Shkodër KUK ËSI T Gur i Zi Kukës Rrapë Kolsh Shkodër Qerret Qafë Mali ´ Ana e Vau i Dejës Shtiqen Zapod Pukë Malit Berdicë Surroj Shtiqen 20°E 21°E Created 16 Dec 2019 / UTC+01:00 A1 Map shows the average precipitation for December in Albania. Map Document MA016_Alb_Ave_Precip_Dec Settlements Borders Projection & WGS 1984 UTM Zone 34N B1 CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL Datum City COUNTIES Tiranë C1 MUNICIPALITIES Albania: Average Produced by MapAction ADMIN 3 mapaction.org Precipitation for D1 0 2 4 6 8 10 [email protected] Precipitation (mm) December kilometres Supported by Supported by the German Federal E1 Foreign Office. - Sheet A1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Data sources 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 - - - 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 The depiction and use of boundaries, names and - - - - - - - - - - - - - F1 .1 .1 .1 GADM, SRTM, OpenStreetMap, WorldClim 0 0 0 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 associated data shown here do not imply 6 7 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 endorsement or acceptance by MapAction. -

Perzierja Dhe Hollimi I Produkteve Te Pastrimit Dhe Te Trajtimit Te Ujit Te Pijshem”

PERMBLEDHJE JOTEKNIKE PËR AKTIVITETIN: “Perzierja dhe hollimi I produkteve te pastrimit dhe te trajtimit te ujit te pijshem” Vendodhja: Rruga “Ura Beshirit”, fshati Lalm, Njesia Administrative Vaqarr, Bashkia Tirane. Kërkues: Subjekti: “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh Janar, 2021 1 TË PERGJITHSHME Subjekti juridik “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh me administrator Z. Leonardo Volpicella, është regjistruar në QKB me NUIS, L21409008V për ushtrimin e veprimtarisë në fusha te ndryshme ku perfshihet edhe: Prodhim, perpunim dhe tregtim te produkteve kimike ne pergjithesi dhe dytesore qe kane perdorim te ndryshem si industriale, ekologjike, farmaceutike, kozmetike dhe shtepiake, detergjent, detersive dhe produkte higjene; produkte per trajtimin e ujerave; produkte per trajtimin dhe riciklimin e mbetjeve urbane dhe/ose industriale dhe toksike; prodhim dhe/ose te materialeve plastike dhe derivate; drejtim, mirembajtje, kontroll, nepermjet menaxhimit te duhur te impianteve te ujerave te pishem me paradisinfektim, aglomerizim, filtrim i shpetje dhe postdezinfektim i ujerave siperfaqesore te lumenjeve, liqeneve dhe te ngjashme nepermjet impianteve te posacme te ngritjes me cfaredolloje fuqie si dhe pastrimin e ujerave shkarkues; ndertim dhe menaxhim i impianteve te pastrimit, dezinfektim i ambienteve, perpunim dhe depozitim per llogari te te treteve te produkteve kimike, kerkim dhe zhvillim i produkteve dhe teknologjive te reja lidhur me objektin e shoqerise. Subjekti “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh ushtron aktivitetin e tij në adresën: Rruga “Ura Beshirit”, fshati Lalm, Njesia Administrative Vaqarr, Bashkia Tirane. 2 PËRSHKRIM I PROJEKTIT 2.1 Qëllimi iprojektit Qëllimi i funksionimit te ketij aktiviteti eshte ofrimi i produkteve kimike te nevojshme per tregun vendas. Keto produkte jane te kerkuara nga konsumatori dhe te domosdoshme per mbarefunksionimin e nje sere aktivitetesh dhe ofrimin e disa sherbimeve private ose publike. -

Tirana Area and Other Regions of Albania and Is Now Considered a Leading NGO in Albania in Supporting the Development of Sustainable Lifestyles and Green Economy

Description of the organization: The Institute for Environmental Policy (IEP) is a non-governmental, non-profit environmental organization founded in November 2008. IEP's general objective is to enhance environmental sustainability in Albania through the implementation of projects aimed to raise awareness among the local population and to formulate environmentally friendly policies in collaboration with local and national authorities. IEP was founded by a group of young experts committed to bringing about positive change after years of environmental degradation and negligence in Albania. IEP members are highly motivated and have the required experience and education to influence the Albanian society towards a sound environmental protection and sustainable living. In its activities, IEP frequently cooperates with other NOGs, local and international experts and volunteers from the local youth. EP has implemented various projects and activities and has experience in awareness raising, trainings, seminars, campaigns and working with youth; this is done connecting different spheres of the Albanian society with a particular attention at the sustainability of activities and processes. IEP has also implemented several public actions on pollution and environmental sustainability with the help of young volunteers in the Tirana area and other regions of Albania and is now considered a leading NGO in Albania in supporting the development of sustainable lifestyles and green economy. IEP was a partner organization with Ethical Links during the "Developing green skills and behaviors" Youth Exchange, organized in Estonia in June 2013. IEP is currently working with local and international young volunteers in IEP, (currently there are two EVS volunteers from Italy, project 2014-3-IT03-KA105-005030), training them on how to manage projects, teaching them environmental management, and is also helping them in learning new foreign languages (in the case of foreign volunteers, the staff of IEP is teaching them Albanian). -

Qarku Tiranë

Qarku Tiranë © Guida e Qarkut Tiranë: Këshilli i Qarkut Tiranë Përgatiti: Elton NOTI Lorena TOTONI Punimet Grafike: Albert HITOALIAJ Fotografë: Albert CMETA Gentian ZAGORÇANI Kontribuan nga arkivat e tyre: Prof.Dr. Perikli QIRIAZI etj GUIDË Itineraret turistike: HighAlbania Mountain Club Printimi : Shtypshkronja " Mediaprint" Adresa: Rr. "Sabaudin Gabrani", ish-fabrika Misto Mame, Tiranë TIRANË 2012 Guida [shqip].pmd 2-3 5/19/2012, 10:02 PM KËSHILLI I QARKUT Guida [shqip].pmd 4-5 5/19/2012, 10:02 PM Rrethi i Tiranës VIZIONI Bashkia Tiranë VIZIONI Bashkia Kamëz Bashkia Vorë Komuna Baldushk Komuna Bërxullë Komuna Bërzhitë Komuna Dajt Komuna Farkë Komuna Kashar Vizioni ynë është që të ofrojmë shërbime sa më të Komuna Krrabë përgjegjshme dhe efikase, duke kontribuar për ta bërë Qarkun e Tiranës një vend të begatë për të Komuna Ndroq jetuar e punuar, në funksion të zhvillimit dhe mirëqenies së komunitetit. Ne besojmë se vlerat e mrekullueshme historike, kulturore, mjedisore Komuna Paskuqan dhe turistike që ka në një destinacion me të vërtetë tërheqës dhe që Komuna Petrelë ofron oportunitete të shumta për të gjithë. Komuna Pezë Komuna Prezë ky rajon do ta Komuna Shëngjergj Komuna Vaqarr Komuna Zall-Bastar shndërrojnë atë Komuna Zall-Herr Rrethi i Kavajës Bashkia Kavajë Bashkia Rrogozhinë Komuna Golem Komuna Gosë Komuna Helmës Komuna Kryevidh Komuna Lekaj Komuna Luz i Vogël Komuna Sinaballaj Komuna Synej Guida [shqip].pmd 6-7 5/19/2012, 10:02 PM në Veri. të malit të Dajtit, nga gryka e Skoranës në Ndodhet Juglindje, aty ku del lumi Erzen. Fshatrat pikërisht mes kryesorë të kësaj rrethine janë: Gurra, Brari, kodrave të Kavajës Priska e Madhe, Lanabregasi, Linza, Tujani, në Lindje dhe atyre të Zall-Herri, Priska e Vogël, Selita e Vogël etj. -

Preventivues Pergj.Sek.Projektimi Ing.Ademar QOSHJA Ing

DEPARTAMENTI INXHINIERIK MIRATOI SEKTORI I PROJEKTIMIT DREJTORI I PËRGJITHSHËM REDI MOLLA P R E V E N T I V TOTAL EMERTIMI I OBJEKTIT: SHERBIME TE INTEGRUARA DHE FURNIZIM VENDOSJE TE PAISJEVE ELEKTRONIKE INVESTITORI: U.K.T.Sh.a SIPERMARRESI: U.K.T.sh.a Furnizim me Sistem Energji Punime Nr. Emërtimi I Objektit Kamera+Siste Elektrike dhe Ndertimore+Puni m Alarmi Ndricim me te Ndryshme Territori 1 STP+Depo Picalle - - - 2 STP Hekal - - - 3 STP Shytqj - - - 4 STP Qeha - - - 5 STP+Depo Kacone - - - 6 STP+Depo Mullet - - - 7 Depo Daias - - - 8 Depo Barbas - - - 9 Depo Fikas - - - 10 Depo Qeha - - - 11 Depo Shytaj - - - 12 Depo Tagan - - - 13 Depo Mullet - - - 14 Depo Picalle - - - 15 Depo Petrele - - - 16 Depo Hekal - - - 17 Depo Gurre e Madhe - - - 18 Depo Vishnje - - - 19 STP Liqeni Thate - - - 20 Depo Liqeni Thate - - - 21 Depo Kala Preze - - - 22 STP Preze - - - 23 STP Preze 2 (Koder Preze) - - - 24 STP Fushe Preze - - - 25 Depom Kukunje - - - 26 Depo Arbane Vaqarr - - - 27 STP Vishnje - - - 28 Depo Sharre - - - 29 STP Zhurje - - - 30 STP Grece - - - 31 STP+Depo Lagje e Re - - - 32 STP+Depo Peze Celje - - - 33 STP+Depo Peze Helmes - - - 34 STP Vaqarr - - - 35 STP Bulltice Vaqarr (Arbane) - - - 36 Depo Peze e Vogel - - - 37 Depo Varrosh - - - 38 Depo Maknor - - - 39 Depo Pajan 1 - - - 40 Depo Pajan - - - 41 Depo Grece - - - 42 Depo Alshet - - - 43 Depo Gellbresh Lagjia Ceke - - - 44 Depo Curret Lagje e Re - - - 45 Depo Dedjet - - - 46 Depo Lagje e Re Pajont - - - 47 Depo Vaqarr 2 - - - 48 Depo Zhurje - - - 49 Depo Vaqarr - - - 50 Depo Bulqve -

ADRESA E E-MAIL Ilir Domi [email protected]

Nr. SHKOLLA Lloji Drejtori ADRESA E E-MAIL 1 AHMETAQ 9-vjeçare Ilir Domi [email protected] 2 ARBANE 9-vjeçare Enkelejda Topalli [email protected] 3 BASTAR I MESEM 9-vjeçare Sadete Duka [email protected] 4 BERXULL 9-vjeçare Zyra Prençi [email protected] 5 BERZHITE 9-vjeçare Beqir Hyka [email protected] 6 FARKE E VOGEL 9-vjeçare Xhelal Qoku [email protected] 7 FERRAJ 9-vjeçare Dorina Llalla [email protected] 8 FUSHAS 9-vjeçare Dëfrim Aga [email protected] 9 FUSHE PREZE 9-vjeçare Dashamir Shamku [email protected] 10 GJOKAJ 9-vjeçare Fatmir Çali [email protected] 11 GROPAJ 9-vjeçare Artan Allgjata [email protected] 12 HAKI SHEHU 9-vjeçare Endri Hamzaraj [email protected] 13 IBE SIPER 9-vjeçare Alma Asllani [email protected] 14 KASEM SHIMA 9-vjeçare Hasime Lamaj [email protected] 15 KASHAR-KODER 9-vjeçare Rajmonda Halili [email protected] 16 KATUND I RI 9-vjeçare Arjan Gjoka [email protected] 17 KOÇAJ 9-vjeçare Erald Dapi [email protected] 18 KUS 9-vjeçare Enver Hidri [email protected] 19 LAGJE E RE 9-vjeçare Arben Rexhepi [email protected] 20 LALM 9-vjeçare Agron Banushi [email protected] 21 LUNDER 9-vjeçare Alma Kaziu [email protected] 22 MANGULL 9-vjeçare Saimir Qordja [email protected] 23 MARQINET 9-vjeçare Agim Korriku [email protected] 24 MEZEZ-FUSHE 9-vjeçare Valbona Jahja [email protected] 25 MJULL BATHORE 9-vjeçare Edmond Sogani [email protected] 26 -

Lista E Kontratave Te Lidhura Ne Drq Tirane

LISTA E KONTRATAVE TE LIDHURA NE DRQ TIRANE Nr /Dt e Vlera e Gjatesi lidhjes Segmentet rrugore Kontraktori Supervizori Kontrates me a Kontrates TVSH K/Rr. Nr. 54 (Trau Dajt) - Deg. dj. maja e Dajtit, Deg. dj. maja e Dajtit - St. GJOKA teleferikut, Deg. dj. maja e K - 2 30.12.2015 - KONSTRUKSION Dajtit - Vila Qeveritare, Vila 1 30.12.2017 2 81.6 administrator Z. Gjeokonsult shpk 95.992.158 Qeveritare - maja e Dajtit, vjeçare Rrok Gjoka Cel. Tiranë (Fresku) - Surrel, 0692027997 Surrel - Qafë Priskë, Qafë Priskë - deg. dj. Q. Mollë,deg. dj K/Sauk – Senatorium, K/Sauk – Ibë, Ibë – Qafë Krrabë (Km 29), Qafë Krrabë (Km 29) – rot. re VICTORIA INVEST K - 3 31.12.2015 - Shijon, rot. re Shijon – Ura Admin. Zj. Valbona 2 31.12.2017 2 e Zaranikës, K/Km 22 – 74.05 Gjeokonsult shpk 137.681.240 Kuci Cel. vjeçare Qytezë Krrabë, Qytezë 0696552291 Krrabë – Pika Sipër Radio, Degëzim Miniera – Objekti X, Rotondo Sauk – Sauk i Vjetër, Uzi Fushë Krujë (deg. Y) - Fushë Krujë (qendër), Fushë Krujë (qendër) - K/Thumanë Qendër, K/Thumanë K - 5 30.12.2015 - JUBICA admin Z. Qendër - Ura e Drojës (aksi 3 30.12.2017 2 72 Ndoc KULLA , Cel. Gjeokonsult shpk 98.395.910 i vjetër ), Fushë Krujë - vjeçare 0694005877 Halilaj, Halilaj - Krujë, K/Rr. Kombëtare (e vjetra) - Bilaj (Llixha),K/Rr. Kombëtare (e vjetra) - Fabrike e Çimentos K/Shirgjan (K/Rr.Nr.70) - Llixha, Llixha - Kaçivel (k.Gramsh), K/Llixhë - K - 7 18.12.2015 - Mjekëz (Uzinë), Elbasan - ALKO IMPEX Admin 4 18.12.2017 2 Gjinar, k/Drizë (k/rr. -

Dwelling and Living Conditions

Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC ALBANIA DWELLING AND LIVING CONDITIONS M a y, 2 0 1 4 ALBANIA DWELLING AND LIVING CONDITIONS Preface and Acknowledgment May, 2014 The 2011 Population and Housing Census of Albania is the 11th census performed in the history of Director of the Publication: Albania. The preparation and implementation of this commitment required a significant amount Gjergji FILIPI, PhD of financial and human resources. For this INSTAT has benefitted by the support of the Albanian government, the European Union and international donors. The methodology was based on the EUROSTAT and UN recommendations for the 2010 Population and Housing Censuses, taking into INSTAT consideration the specific needs of data users of Albania. Ledia Thomo Anisa Omuri In close cooperation with international donors, INSTAT has initiated a deeper analysis process in Ruzhdie Bici the census data, comparing them with other administrative indicators or indicators from different Eriona Dhamo surveys. The deepened analysis of Population and Housing Census 2011 will serve in the future to better understand and interpret correctly the Albanian society features. The information collected by TECHNICAL ASSISTENCE census is multidimensional and the analyses express several novelties like: Albanian labour market Juna Miluka and its structure, emigration dynamics, administrative division typology, population projections Kozeta Sevrani and the characteristics of housing and dwelling conditions. The series of these publications presents a new reflection on the situation of the Albanian society, helping to understand the way to invest in the infrastructure, how to help local authorities through Copyright © INSTAT 2014 urbanization phenomena, taking in account the pace of population growth in the future, or how to address employment market policies etc. -

Transporti Rrugor.Xlsx

ANEKSI nr.2 "Raporti i Shpenzimeve të Programit sipas Artikujve Buxhetorë" 12 MUJORI ne 000/leke Emri i Grupit ..... Kodi i Grupit .... Programi TRANSPORTI RRUGOR Kodi i Programit ..... (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)=(6)-(5) Fakti PBA Buxheti Vjetor Buxheti Vjetor Buxheti Vjetor Fakti Art. Emertimi i vitit Plan i Plani i i Plan Plan Fillestar Viti Diferenca paraardhes Rishikuar Viti Periudhes/progr Periudhes/progr Viti 2018 2018 Viti 2017 2018 esiv esiv 600 Paga 116,260 155,900 155,900 132,130 132,130 129,616 -2,514 601 Sigurime Shoqërore 19,293 26,990 26,990 22,609 22,609 21,500 -1,109 602 Mallra dhe Shërbime të Tjera 1,824,639 1,732,570 1,732,370 1,728,113 1,728,113 1,718,903 -9,210 603 Subvencione 0 0 604 Transferta Korente të Brendshme 0 0 605 Transferta Korente të Huaja 0 0 606 Trans per Buxh. Fam. & Individ 228 0 51,411 51,411 51,411 0 Nen-Totali Shpenzime Korrente 1,960,420 1,915,460 1,915,260 1,934,263 1,934,263 1,921,430 -12,833 230 Kapitale të Patrupëzuara 511,520 300,000 300,000 400,914 400,914 399,514 -1,400 231 Kapitale të Trupëzuara 11,622,649 14,855,041 14,855,041 15,000,127 15,000,127 14,881,053 -119,074 232 Transferta Kapitale 0.0 0 Shpenzime Kapitale me financim te Nen -Totali 12,134,169 15,155,041 15,155,041 15,401,041 15,401,041 15,280,567 -120,474 brendshem 230 Kapitale të Patrupëzuara 20,000.0 29,000 29,000 29,000 -29,000 231 Kapitale të Trupëzuara 7,325,000.0 7,316,000 6,309,100 6,309,100 6,309,100 0 232 Transferta Kapitale 0.0 0 Nen -Totali Shpenzime Kapitale me financim te huaj 9,204,682 7,345,000 7,345,000 6,338,100