Linear Electric Motors for Aerospace Launch Assist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naval Postgraduate School

NPS-97-06-003 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA SHIP ANTI BALLISTIC MISSILE RESPONSE (SABR) by LT Allen P. Johnson LT David C. Leiker LT Bryan Breeden ENS Parker Carlisle LT Willard Earl Duff ENS Michael Diersing LT Paul F. Fischer ENS Ryan Devlin LT Nathan Hornback ENS Christopher Glenn TDSI Students LT Chris Hoffmeister, USN LT John Kelly, USN LTC Tay Boon Chong, SAF LTC Yap Kwee Chye, SAF MAJ Phang Nyit Sing, SAF CPT Low Wee Meng, SAF CPT Ang Keng-ern, SAF CPT Ohad Berman, IDF Mr. Fann Chee Meng, DSTA, Singapore Mr. Chin Chee Kian, DSTA, Singapore Mr. Yeo Jiunn Wah, DSTA, Singapore June 2006 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for: Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Requirements and Programs (OPNAV N7), 2000 Navy Pentagon, Rm. 4E392, Washington, D.C. 20350-2000 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. -

Investigation, Analysis and Design of the Linear Brushless Doubly-Fed

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Farroh Seifkhani for the degree of Master of Science in Electrical and Computer Engineering presented on February 8, 1991 . Title: Investigation, Analysis and Design of the Linear Brush less Doubly-Fed Machine.Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: K. Wallace This thesis covers theefforts of thedesign, analysis, characteristics, and construction of a Linear Brush less Doubly-Fed Machine (LBDFM), as well as the results of the investigations and comparison with its actual prototype. In recent years, attempts to develop new means of high-speed, efficient transportation have led to considerable world-wide interest in high-speed trains. This concern has generated interests in the linear induction motor which has been considered as one of the more appropriate propulsion systems for Super-High-Speed Trains (SHST). Research and experiments on linear induction motors arebeing actively pursued in a number of countries. Linear induction motors are generally applicable for the production of motion in a straight line, eliminating the need for gears and other mechanisms for conversion of rotational motion to linear motion. The idea of investigation and construction of the linear brushless doubly-fed motor was first propounded at Oregon State University, because of potential applications as Variable-Speed Transportation (VST) system. The perceived advantages of a LBDFM over other LIM's are significant reduction of cost and maintenance requirements. The cost of this machine itself is expected to be similar to that of a conventionalLIM. However, it is believed that the rating of the power converter required for control of the traveling magnetic wave in the air gap is a fraction of the machine rating. -

Lyall Cooper Dr. Dann ASR – D Block 10 May 2012 the Mighty Railgun I. Abstract the Idea of This Project Is to Build a Railgun

Lyall Cooper Dr. Dann ASR – D Block 10 May 2012 The Mighty Railgun (All Bark no Bite) I. Abstract The idea of this project is to build a railgun capable of firing a small metal projectile at substantial velocity. The original plan was to build iterative prototypes capable of firing small projectiles, and using them to figure out the ideal design for the final version, but the smaller versions were not very successful due to their relative lack of power, so it was difficult to use them to learn what to do. The final, largest scale railgun is powered by a bank of capacitors with an equivalent capacitance of 24.6mF charged to around 350V. This produces 3013.5J of energy discharged over approximately 58.75 µs (it varies for each firing), drawing a peak of about 1425A when firing a projectile (it once again varies) and about 1600A when not firing a projectile (short circuiting the rails). The railgun is capable of consistently firing a small piece of metal (usually aluminum or copper); however the projectile does not usually travel very far, although this is hard to measure due to the nature of the gun and the speed at which the firing takes place. II. Introduction Electricity is often seemingly mysterious, but we have come to accept and understand how through the interaction of electric and magnetic fields we can create a simple motor, as we did in the first semester. A railgun is just a linear electric motor, at very high speeds. What makes it different, however, is that it uses neither magnets nor coils of wire, and relies entirely on the induced magnetic field in the rails due to the extremely large current to produce a Lorentz Force to propel the projectile (which will be discussed in greater depth in the theory section). -

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION to TUBULAR LINEAR MOTORS Linear Motors Provide Direct Thrust for Positioning a Payload, Eliminating the Need for Rotary-To-Linear Conversion

PRODUCT OVERVIEW – DIRECT-DRIVE LINEAR MOTOR SYSTEMS A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO TUBULAR LINEAR MOTORS Linear motors provide direct thrust for positioning a payload, eliminating the need for rotary-to-linear conversion. The three main direct-drive linear motion systems on the market today – iron-core, U-channel, and tubular linear motors – each have distinct advantages and disadvantages with respect to specific applications, for example regarding form factor, achievable force density, and efficiency. Understanding the differences will enable a designer to select the best motor option. Iron-core motor • Magnetic saturation The basic structure of the iron-core motor (Figure 1) is When the generated forces are pushed beyond the similar to that of an unrolled rotary motor with discrete normal operating range, the iron will reach magnetic stator and magnetic poles. It has a set of electromagnetic saturation and the force-to-current relationship coils wrapped around an iron core. The end effect of this is becomes non-linear, making control more difficult. to increase the amount of magnetic field generated by the • Large footprint coils, as the iron will contribute to the generated field The basic construction of iron-core motors requires a through realigning microscopic magnetic domains in the fairly large footprint. iron with the magnetic field from the coils. This is the major • Lateral and attractive (non-useful) forces advantage of the iron-core motor: for a given input of These forces are inherent to the motor design and current, a significant amount of force can be generated. require additional constraints. However, there are some disadvantages/behaviours that U-channel motor have to be considered: One of the main features of the U-channel motor (Figure 2) • Cogging is the absence of iron from the critical locations in the This is the movement of the motor’s iron forcer so as to motor. -

High Speed Linear Induction Motor Efficiency Optimization

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2005-06 High speed linear induction motor efficiency optimization Johnson, Andrew P. (Andrew Peter) http://hdl.handle.net/10945/11052 High Speed Linear Induction Motor Efficiency Optimization by Andrew P. Johnson B.S. Electrical Engineering SUNY Buffalo, 1994 Submitted to the Department of Ocean Engineering and the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Naval Engineer and Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2005 ©Andrew P. Johnson, all rights reserved. MIT hereby grants the U.S. Government permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of A uthor ................ ............................... D.epartment of Ocean Engineering May 7, 2005 Certified by. ..... ........James .... ... ....... ... L. Kirtley, Jr. Professor of Electrical Engineering // Thesis Supervisor Certified by......................•........... ...... ........................S•:• Timothy J. McCoy ssoci t Professor of Naval Construction and Engineering Thesis Reader Accepted by ................................................. Michael S. Triantafyllou /,--...- Chai -ommittee on Graduate Students - Depa fnO' cean Engineering Accepted by . .......... .... .....-............ .............. Arthur C. Smith Chairman, Committee on Graduate Students DISTRIBUTION -

Stepping Motors Fundamentals

AN907 Stepping Motors Fundamentals Author: Reston Condit TYPES OF STEPPING MOTORS Microchip Technology Inc. There are three basic types of stepping motors: Dr. Douglas W. Jones permanent magnet, variable reluctance and hybrid. University of Iowa This application note covers all three types. Permanent magnet motors have a magnetized rotor, while variable reluctance motors have toothed soft-iron rotors. Hybrid INTRODUCTION stepping motors combine aspects of both permanent Stepping motors fill a unique niche in the motor control magnet and variable reluctance technology. world. These motors are commonly used in measure- The stator, or stationary part of the stepping motor ment and control applications. Sample applications holds multiple windings. The arrangement of these include ink jet printers, CNC machines and volumetric windings is the primary factor that distinguishes pumps. Several features common to all stepper motors different types of stepping motors from an electrical make them ideally suited for these types of point of view. From the electrical and control system applications. These features are as follows: perspective, variable reluctance motors are distant 1. Brushless – Stepper motors are brushless. The from the other types. Both permanent magnet and commutator and brushes of conventional hybrid motors may be wound using either unipolar motors are some of the most failure-prone windings, bipolar windings or bifilar windings. Each of components, and they create electrical arcs that these is described in the sections below. are undesirable or dangerous in some environments. Variable Reluctance Motors 2. Load Independent – Stepper motors will turn at Variable Reluctance Motors (also called variable a set speed regardless of load as long as the switched reluctance motors) have three to five load does not exceed the torque rating for the windings connected to a common terminal. -

An Introductory Electric Motors and Generators Experiment for a Sophomore Level Circuits Course

AC 2008-310: AN INTRODUCTORY ELECTRIC MOTORS AND GENERATORS EXPERIMENT FOR A SOPHOMORE-LEVEL CIRCUITS COURSE Thomas Schubert, University of San Diego Thomas F. Schubert, Jr. received his B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from the University of California, Irvine, Irvine CA in 1968, 1969 and 1972 respectively. He is currently a Professor of electrical engineering at the University of San Diego, San Diego, CA and came there as a founding member of the engineering faculty in 1987. He previously served on the electrical engineering faculty at the University of Portland, Portland OR and Portland State University, Portland OR and on the engineering staff at Hughes Aircraft Company, Los Angeles, CA. Prof. Schubert is a member of IEEE and ASEE and is a registered professional engineer in Oregon. He currently serves as the faculty advisor for the Kappa Eta chapter of Eta Kappa Nu at the University of San Diego. Frank Jacobitz, University of San Diego Frank G. Jacobitz was born in Göttingen, Germany in 1968. He received his Diploma in physics from the Georg-August Universität, Göttingen, Germany in 1993, as well as M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA in 1995 and 1998, respectively. He is currently an Associate Professor of mechanical engineering at the University of San Diego, San Diego, CA since 2003. From 1998 to 2003, he was an Assistant Professor of mechanical engineering at the University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA. He has also been a visitor with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique at the Université de Provence (Aix-Marseille I), France. -

ELECTRICAL ENERGY UTLISATION Jacek F

ELECTRICAL ENERGY UTLISATION Jacek F. Gieras and Izabella A. Gieras Adam Marszalek Publishing House, Torun, 1998 This text evolved from notes used in teaching an undergraduate course Energy Utilisation at the University of Cape Town. As the curricula of electrical engineering programmes became more and more overcrowded, many electrical engineering departments decided to limit the number of compulsory courses in heavy current electrical engineering. As a result, the number of lectures in electrical machines and related subjects have been reduced. Under such circumstances students need a concise textbook which covers electrical motors with emphasis on their performance, selection and applications, characteristics of modern electrical drives including variable speed drives and the use of electrical energy in households. This textbook deals with fundamentals of electrical motors, drives, electrical traction and domestic use of electrical energy. It is intended to serve second or third year students taking a one-semester course in energy utilisation or electric power engineering. Transformers and electromechanical generators have been omitted as transformation and generation of electric power is usually covered by a parallel course in power systems. The textbook consists of seven chapters: 1. Energy and drives, 2. D.c. motors, 3. Three- phase induction motors, 4. Synchronous motors, 5. Variable-speed drives, 6. Electrical traction and 7. Domestic use of electrical energy. Chapter 7 also contains principles of illumination. For a one semester course and two lectures per week the authors recommend the first four chapters. For four lectures per week the authors recommend all seven chapters. Students using this textbook should have taken courses in circuit theory and electromagnetism as prerequisites. -

Industrial Linear Motors

Industrial Linear Motors Smart solutions are driven by PRODUCT OVERVIEW www.linmot.com Precision and dynamics In the products and in the everyday life of NTI AG, these values are inseparable. NTI AG NTI AG is a global manufacturer of high quality tubular style linear motors and linear motor systems and thus focuses on the development, production and distribution of linear direct drives for use in industrial environments. Founded in 1993 as an independent business unit of the Sulzer Group, NTI AG has been in operation since 2000 as an independent company. NTI AG headquarters are located in Spreitenbach, near Zurich in Switzerland. In addition to three production sites in Switzerland and Slovakia, NTI AG maintains a sales and support office LinMot® USA Inc. to cover the Americas. Mission The brands LinMot® for industrial linear motors and MagSpring® for magnetic springs are offered LinMot offers its customers a sophisticated and dedicated linear to customers worldwide. NTI AG drive system that can be easily integrated into all leading control maintains an experienced customer systems. A high degree of standardization, delivery from stock and consultant sales and support a worldwide distribution network insure the immediate availability network of over 80 locations and excellent customer support. worldwide. For the realization of linear motion Our aim is to push linear direct drive technology and make it a NTI AG is always a competent and standard machine design element. We offer highly efficient drive reliable partner. solutions that make a major contribution to the overall resource conservation effort. 2 3 Linear Motors Position and Temperature sensors Electronic nameplate Stator Winding Slider with Neodynium Magnets Payload Mounting LinMot linear motors employ a direct electromagnetic principle. -

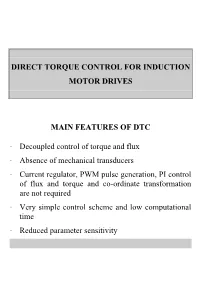

Direct Torque Control of Induction Motors

DIRECT TORQUE CONTROL FOR INDUCTION MOTOR DRIVES MAIN FEATURES OF DTC · Decoupled control of torque and flux · Absence of mechanical transducers · Current regulator, PWM pulse generation, PI control of flux and torque and co-ordinate transformation are not required · Very simple control scheme and low computational time · Reduced parameter sensitivity BLOCK DIAGRAM OF DTC SCHEME + _ s* s j s + Djs _ Voltage Vector s * T + j s DT Selection _ T S S S s Stator a b c Torque j s s E Flux vs 2 Estimator Estimator 3 s is 2 i b i a 3 Induction Motor In principle the DTC method selects one of the six nonzero and two zero voltage vectors of the inverter on the basis of the instantaneous errors in torque and stator flux magnitude. MAIN TOPICS Þ Space vector representation Þ Fundamental concept of DTC Þ Rotor flux reference Þ Voltage vector selection criteria Þ Amplitude of flux and torque hysteresis band Þ Direct self control (DSC) Þ SVM applied to DTC Þ Flux estimation at low speed Þ Sensitivity to parameter variations and current sensor offsets Þ Conclusions INVERTER OUTPUT VOLTAGE VECTORS I Sw1 Sw3 Sw5 E a b c Sw2 Sw4 Sw6 Voltage-source inverter (VSI) For each possible switching configuration, the output voltages can be represented in terms of space vectors, according to the following equation æ 2p 4p ö s 2 j j v = ç v + v e 3 + v e 3 ÷ s ç a b c ÷ 3 è ø where va, vb and vc are phase voltages. -

Difference Between Bipolar Drives and Unipolar Drives for Stepper Motors

WHITE PAPER DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BIPOLAR DRIVES AND UNIPOLAR DRIVES FOR STEPPER MOTORS orking on a motorized development requires some knowledge about motors and controllers. This article Wis focused on the stepper motors which is a type of brushless DC motor with a high number of poles. This technology is generally driven in open loop without any feedback sensor, meaning the current is typically applied on the phases without knowing the rotor position. The rotor moves to be aligned with the stator magnetic flux, then the current can be supplied to the next phase. We will consider two ways to supply current in the coil: bipolar way and unipolar way. In this article, we will explain the differences of bipolar and unipolar motors and driving methods. We will show the advantages and limits of both technologies. Let’s take an example of a four step, permanent magnet stepper motor (see figure 1). The rotor is made with a one pole pair magnet, and the stator is composed of two phases, Phase A and Phase B. • In unipolar: the current always flows in the same direction. Each coil is dedicated to one current direction, meaning either the coil A+ or the coil A- is powered. The coils A+ and A- are never powered together. • In bipolar: the current can flow in both directions in all coils. The phases A+ and A- are powered together. A bipolar motor requires one coil minimum per phase and unipolar motor Figure 1. 4-Step Stepper Motor requires two coils minimum per phase. Let’s review both options in more detail. -

An Engineering Guide to Soft Starters

An Engineering Guide to Soft Starters Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 General 1.2 Benefits of soft starters 1.3 Typical Applications 1.4 Different motor starting methods 1.5 What is the minimum start current with a soft starter? 1.6 Are all three phase soft starters the same? 2 Soft Start and Soft Stop Methods 2.1 Soft Start Methods 2.2 Stop Methods 2.3 Jog 3 Choosing Soft Starters 3.1 Three step process 3.2 Step 1 - Starter selection 3.3 Step 2 - Application selection 3.4 Step 3 - Starter sizing 3.5 AC53a Utilisation Code 3.6 AC53b Utilisation Code 3.7 Typical Motor FLCs 4 Applying Soft Starters/System Design 4.1 Do I need to use a main contactor? 4.2 What are bypass contactors? 4.3 What is an inside delta connection? 4.4 How do I replace a star/delta starter with a soft starter? 4.5 How do I use power factor correction with soft starters? 4.6 How do I ensure Type 1 circuit protection? 4.7 How do I ensure Type 2 circuit protection? 4.8 How do I select cable when installing a soft starter? 4.9 What is the maximum length of cable run between a soft starter and the motor? 4.10 How do two-speed motors work and can I use a soft starter to control them? 4.11 Can one soft starter control multiple motors separately for sequential starting? 4.12 Can one soft starter control multiple motors for parallel starting? 4.13 Can slip-ring motors be started with a soft starter? 4.14 Can soft starters reverse the motor direction? 4.15 What is the minimum start current with a soft starter? 4.16 Can soft starters control an already rotating motor (flying load)? 4.17 Brake 4.18 What is soft braking and how is it used? 5 Digistart Soft Starter Selection 5.1 Three step process 5.2 Starter selection 5.3 Application selection 5.4 Starter sizing 1.