NSIAD-91-3 Army Force Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Army Leadership

8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 2 Leadership Track Section 1 INTRODUCTION TO ARMY LEADERSHIP Key Points 1 What Is Leadership? 2 The Be, Know, Do Leadership Philosophy 3 Levels of Army Leadership 4 Leadership Versus Management 5 The Cadet Command Leadership Development Program e All my life, both as a soldier and as an educator, I have been engaged in a search for a mysterious intangible. All nations seek it constantly because it is the key to greatness — sometimes to survival. That intangible is the electric and elusive quality known as leadership. GEN Mark Clark 8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 3 Introduction to Army Leadership ■ 3 Introduction As a junior officer in the US Army, you must develop and exhibit character—a combination of values and attributes that enables you to see what to do, decide to do it, and influence others to follow. You must be competent in the knowledge and skills required to do your job effectively. And you must take the proper action to accomplish your mission based on what your character tells you is ethically right and appropriate. This philosophy of Be, Know, Do forms the foundation of all that will follow in your career as an officer and leader. The Be, Know, Do philosophy applies to all Soldiers, no matter what Army branch, rank, background, or gender. SGT Leigh Ann Hester, a National Guard military police officer, proved this in Iraq and became the first female Soldier to win the Silver Star since World War II. Silver Star Leadership SGT Leigh Ann Hester of the 617th Military Police Company, a National Guard unit out of Richmond, Ky., received the Silver Star, along with two other members of her unit, for their actions during an enemy ambush on their convoy. -

The Army's New Heavy Division Design

R� from AUSA 's Institute of Land Warfare The Army's New Heavy Division Design The Army's New Heavy Division will be more Conservative Heavy Division, was tested through lethal than the present combat force even though it will simulation at the Division AWE at Fort Hood in have fewer soldiers and1 armored vehicles. The new November 1997. design will give the Army a heavy combat division that is strategjcally deployable, agile and flexible. The The most significant design change is the command Army's announcement of the new design follows and control apparatus in the new division involving a almost four years of analysis and experimentation near paperless operation passing information back and involving thousands of soldiers and civilians from the forth via computer-based communications. Information Army's major commands and a number of civilian exchange will be built on a digital communications contractors who partnered with the Army. framework that will allow the new division to cover about three times the battlefield area of today' s division. The current heavy division has served the Army The framework includes an intranet information system since 1984. It was designed to win in a major allowing leaders to see where friendly units are and contingency against Warsaw Pact forces. However, send up-to-the-minute data on enemy locations. The with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact, object is to give soldiers "situational awareness," or the the current 18,000-man heavy division has had to adapt ability to know where they are, where their buddies are to a wider range of varied and unpredictable threats. -

Fm 3-21.5 (Fm 22-5)

FM 3-21.5 (FM 22-5) HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 2003 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. *FM 3-21.5(FM 22-5) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 3-21.5 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, DC, 7 July 2003 DRILL AND CEREMONIES CONTENTS Page PREFACE........................................................................................................................ vii Part One. DRILL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. History................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Military Music....................................................................... 1-2 CHAPTER 2. DRILL INSTRUCTIONS Section I. Instructional Methods ........................................................................ 2-1 2-1. Explanation............................................................................ 2-1 2-2. Demonstration........................................................................ 2-2 2-3. Practice................................................................................... 2-6 Section II. Instructional Techniques.................................................................... 2-6 2-4. Formations ............................................................................. 2-6 2-5. Instructors.............................................................................. 2-8 2-6. Cadence Counting.................................................................. 2-8 CHAPTER 3. COMMANDS AND THE COMMAND VOICE Section I. Commands ........................................................................................ -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

The Market for Light Tracked Vehicles

The Market for Light Tracked Vehicles Product Code #F651 A Special Focused Market Segment Analysis by: Military Vehicles Forecast Analysis 2 The Market for Light Tracked Vehicles 2010 - 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents .....................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................................................3 Trends..........................................................................................................................................................................5 Competitive Environment.......................................................................................................................................6 Market Statistics .......................................................................................................................................................8 Table 1 - The Market for Light Tracked Vehicles Unit Production by Headquarters/Company/Program 2010 - 2019.......................................................11 Table 2 - The Market for Light Tracked Vehicles Value Statistics by Headquarters/Company/Program 2010 - 2019 .......................................................15 Figure -

Modernizing Soldier Lethality by Kimball Johnson

Researchers are currently developing the Human-interest Image Detector, a passive brain monitoring system that attempts to detect operator interest in visual scenes. (U.S. Army photo) Modernizing Soldier Lethality By Kimball Johnson odernization" is a concept older than the "We set six priorities: long-range precision fires, invention of repeating rifles and revolvers. next-generation combat vehicles, future vertical lift, Its definition includes the drive to conduct network communications, air and missile defense, and Mresearch and field new technology designed to defend Soldier lethality, spanning all the fundamentals of shoot, the lives of Soldiers and overcome threats on and off the movement, communicate, sustain and protect," McCar- battlefield. thy said.1 With modernization comes the underlying temptation to wonder if future technological advancements in offensive Center for Adaptive Soldier Technologies capabilities by Army scientists could potentially replace Improving Soldier lethality is an ongoing project at Soldiers in the field. Noncommissioned officers, however, ARL's Center for Adaptive Soldier Technologies, located have enough experience with new gear to know technology at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. Research topics can never replace the human factor. Imparting hard-won on their website include cybernetics, "Brain Computer wisdom to their Soldiers, as well as lessons learned from Interface," "The Human Interest Detector," and "The fielding new equipment, will remain the NCO's role. Human Variability Project." Addison Bohannon, a BCI bench scientist, and math- The Army Research Laboratory's Goals ematician with ARL said CAST's purpose is to make new Ryan D. McCarthy, the undersecretary of the Army, technology adaptable to Soldiers' needs. -

The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

CHAPTER 2 Department of the Army Overview when the service launched a “modularity” initiative, the The Department of the Army includes the Army’s active Army was organized for nearly a century around divisions component; the two parts of its reserve component, the (which involved fewer but larger formations, with 12,000 Army Reserve and the Army National Guard; and all to 18,000 soldiers apiece). During that period, units in federal civilians employed by the service. By number of Army divisions could be separated into ad hoc BCTs military personnel, the Department of the Army is the (typically, three BCTs per division), but those units were biggest of the military departments. It also has the largest generally not organized to operate independently at any operation and support (O&S) budget. The Army does command level below the division. (For a description of not have the largest total budget, however, because it the Army’s command levels, see Box 2-1.) In the current receives significantly less funding to develop and acquire structure, BCTs are permanently organized for indepen- weapon systems than the other military departments do. dent operations, and division headquarters exist to pro- vide command and control for operations that involve The Army is responsible for providing the bulk of U.S. multiple BCTs. ground combat forces. To that end, the service is orga- nized primarily around brigade combat teams (BCTs)— The Army is distinct not only for the number of ground large combined-arms formations that are designed to combat forces it can provide but also for the large num- contain 4,400 to 4,700 soldiers apiece and include infan- ber of armored vehicles in its inventory and for the wide try, artillery, engineering, and other types of units.1 The array of support units it contains. -

UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS of ENGINEERS V. HAWKES CO., INC., ET AL

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2015 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS v. HAWKES CO., INC., ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT No. 15–290. Argued March 30, 2016—Decided May 31, 2016 The Clean Water Act regulates “the discharge of any pollutant” into “the waters of the United States.” 33 U. S. C. §§1311(a), 1362(7), (12). When property contains such waters, landowners who dis- charge pollutants without a permit from the Army Corps of Engi- neers risk substantial criminal and civil penalties, §§1319(c), (d), while those who do apply for a permit face a process that is often ar- duous, expensive, and long. It can be difficult to determine in the first place, however, whether “waters of the United States” are pre- sent. During the time period relevant to this case, for example, the Corps defined that term to include all wetlands, the “use, degradation or destruction of which could affect interstate or foreign commerce.” 33 CFR §328.3(a)(3). Because of that difficulty, the Corps allows property owners to obtain a standalone “jurisdictional determination” (JD) specifying whether a particular property contains “waters of the United States.” §331.2. -

Three Levels of War USAF College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education (CADRE) Air and Space Power Mentoring Guide, Vol

Three Levels of War USAF College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education (CADRE) Air and Space Power Mentoring Guide, Vol. 1 Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 1997 (excerpt) Modern military theory divides war into strategic, operational, and tactical levels.1 Although this division has its basis in the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War, modern theory regarding these three levels was formulated by the Prussians following the Franco- Prussian War. It has been most thoroughly developed by the Soviets.2 In American military circles, the division of war into three levels has been gaining prominence since its 1982 introduction in Army Field Manual (FM) 100-5, Operations.3 The three levels allow causes and effects of all forms of war and conflict to be better understood—despite their growing complexity.4 To understand modern theories of war and conflict and to prosecute them successfully, the military professional must thoroughly understand the three levels, especially the operational level, and how they are interrelated. The boundaries of the levels of war and conflict tend to blur and do not necessarily correspond to levels of command. Nevertheless, in the American system, the strategic level is usually the concern of the National Command Authorities (NCA) and the highest military commanders, the operational level is usually the concern of theater commands, and the tactical level is usually the focus of subtheater commands. Each level is concerned with planning (making strategy), which involves analyzing the situation, estimating friendly and enemy capabilities and limitations, and devising possible courses of action. Corresponding to the strategic, operational, and tactical levels of war and conflict are national (grand) strategy with its national military strategy subcomponent, operational strategy, and battlefield strategy (tactics). -

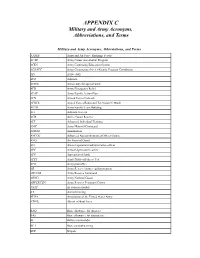

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Frank's Combined 1973 Handout

October War 1973 1 Chadwick Handout ISRAELI DEFENSE FORCE, 1973 Pre-War Organization (Theory) Actual Wartime Organization 36th Armored Division (Eitan) Northern Front 212th Artillery Regiment 212th Artillery Regiment 179th Armored Brigade transferred to 210th Division 679th Armored Brigade 679th Armored Brigade 4th Mechanized Brigade transferred to 146th Division (+7th Armored Brigade, RA) (+188th Armored Brigade, RA) 143rd Armored Division (Sharon) Southern Front 214th Artillery Regiment 214th Artillery Regiment 421st Armored Brigade 421st Armored Brigade 600th Armored Brigade 600th Armored Brigade 875th Mechanized Brigade transferred to 252nd Division (+14th Armored Brigade, RA) 146th Armored Division (Peled) Northern Front (Strategic Reserve Division) 213th Artillery Regiment 213th Artillery Regiment 205th Armored Brigade 205th Armored Brigade 217th Armored Brigade transferred to 162nd Division 670th Mechanized Brigade 670th Mechanized Brigade (+4th Mechanized Brigade) 162nd Armored Division (Adan) Southern Front 215th Artillery Regiment 215th Artillery Regiment 7th Armored Brigade RA transferred to 36th Division pre-war* 460th Armored Brigade RA 460th Armored Brigade, RA (transferred to 252nd Division shortly before the war, then back to 162nd Division when the division reached the front.) 11th Mechanized Brigade transferred to Division Magen/Sassoon (+204th Mechanized Brigade, then transferred to Division Magen/Sassoon) (+217th Armored Brigade) (+500th Separate Armored Brigade) 210th Armored Division (Laner) Northern Front (formed -

ARMY the Army Is Older Than the Country It Serves

Overview YOUR UNITED STATES ARMY The Army is older than the country it serves. Authorized by the Second Continental Congress, the Continental Army was established on 14 June 1775. THE ARMY: • is the oldest and largest of the military departments; • has Soldiers in every state and U.S. territory (Total Army); • is the second largest U.S. employer (Wal-Mart is the largest); • has over 250 Military Occupational Specialties and Officer specialties; and • is the foundation of the Joint Force. Fewer than 1% of Americans currently serve in the military; 79% of Soldiers come from families that have served in the military. People Are Our Army SOLDIERS SERVE AND LIVE BY A SET OF SEVEN COMMON VALUES: LOYALTY DUTY RESPECT SELFLESS SERVICE EVERY SOLDIER HONOR IS A VOLUNTEER INTEGRITY PERSONAL COURAGE Soldiers are not in the Army— Soldiers are the army. Gen. Creighton Abrams, 26th Chief of Staff of the Army America’s Army 1.012 MILLION* 340,216 SOLDIERS PIECES OF EQUIPMENT ~187,000 WORLDWIDE DEPLOYED 284,344 26,232 WHEELED COMBAT VEHICLES VEHICLES 82% 18% MALE FEMALE 20,742 4,300 MRAP AIRCRAFT VEHICLES • 55% Caucasian • 21% African American • 16% Hispanic 4,466 132 • 5% Asian/Pacific Islander STRYKER WATERCRAFT • 3% Other/Unknown VEHICLES *AS OF MAY 21 The American Soldier: Then & Now 1968 2020 (ENLISTED) (ENLISTED) • 22 years old • 28 years old • 79% high school graduates • 96% high school graduates • < 1% female • 18% female • 21% minority • 42% minority • 60% draftees • 100% volunteers • 36% married • 52% married • SGT base pay = $279/mo* • SGT base pay = $3,001/mo • SGLI coverage = $10,000* • SGLI coverage = $400,000 • 35 lbs of equipment • 75+ lbs of equipment ($1,856)* ($19,454) • Individual replacements • Unit rotations • 62% survival rate if wounded • 88% survival rate if wounded * NOT ADJUSTED FOR INFLATION What Your Army Does The U.S.