Authoritarian School Reforms: Ideal and Practices in Fascist Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Thinking Fascism and Populism in Terms of the Past

Introduction Thinking Fascism and Populism in Terms of the Past Representing a historian’s inquiry into how and why fascism morphed into populism in history, this book describes the dicta- torial genealogies of modern populism. It also stresses the sig- nifi cant diff erences between populism as a form of democracy and fascism as a form of dictatorship. It rethinks the conceptual and historical experiences of fascism and populism by assessing their elective ideological affi nities and substantial political dif- ferences in history and theory. A historical approach means not subordinating lived experiences to models or ideal types but rather stressing how the actors saw themselves in contexts that were both national and transnational. It means stressing varied contingencies and manifold sources. History combines evidence with interpretation. Ideal types ignore chronology and the cen- trality of historical processes. Historical knowledge requires accounting for how the past is experienced and explained through narratives of continuities and change over time. Against an idea of populism as an exclusively European or American phenomenon, I propose a global reading of its historical 1 2 / Introduction itineraries. Disputing generic theoretical defi nitions that reduce populism to a single sentence, I stress the need to return populism to history. Distinctive, and even opposed, forms of left- and right- wing populism crisscross the world, and I agree with historians like Eric Hobsbawm that left and right forms of populism cannot be confl ated simply because they are often antithetical.1 While populists on the left present those who are opposed to their politi- cal views as enemies of the people, populists on the right connect this populist intolerance of alternative political views with a con- ception of the people formed on the basis of ethnicity and country of origin. -

Krigen Mot Ryssarna I Vin Också En Utmarkelse Av Den Fin Det Er Imidlertid Tre Artikler Om Program.» Kultur

Stiftelsen norsk Okkupasjonshistorie, 2014 UAVHENGIG AVIS Nr.6 - 1992 - 41. årgang Finsk godgjøreIse KULTUR ER BASISVARE, til utenlandske IKHESTORMARKEDPRODUKT Jeg har skummet dagens A v Frederik Skaubo med overskrift: Rambo eller krigsdeltagere Morgenblad og bl.a. merket Rimbaud? hvor han angriper Efter 50 år får de svenska sol ersattning på knappt 1.500 kro meg datoen, 8. mai, som jo så selv om avskaffelse av familien det syn at staten (myndighe dater som frivilligt hjiilpte Fin nor får alla frivillige utlanningar absolutt gir grunn til ettertanke. var oppført på kommunistenes tene) også har noe ansvar for land i krigen mot ryssarna i vin också en utmarkelse av den fin Det er imidlertid tre artikler om program.» kultur. Han er såvisst ikke opp ter och fortsattningskriget 1939- ska staten. Ersattningen ar mera et annet viktig emne, jeg her fes Et fenomen idag er f.eks. at tatt av kultur som identitets 45 ekonomisk ersattning. en symbolisk gest av Finland tet meg ved. Hver for seg avkla mens Høyre med pondus pro fremmende, tradisjonsbevaren Det var i samband med det som i år firar sitt 75-års jubi rende, tildels avslørende i for klamerer en politikk bygget på de, kvalitetsskapende og estetisk årliga firandet av veterandagen i leum. bindelse med vårt kultursyn. De «det kristne verdigrunnlag ... og etisk oppdragende. Nesten Finland som regeringen fattade Framfor allt fOr de ester som er dessuten aktuelle også når vil forholdet for de flestes ved mer anarkistisk enn liberal går beslut om att hedra de 5.000 frivilligt deltog i striderna på denne avis kommer ut. -

Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, II Author(S): Karl Loewenstein Source: the American Political Science Review, Vol

Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, II Author(s): Karl Loewenstein Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Aug., 1937), pp. 638-658 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1948103 Accessed: 07-08-2018 08:47 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Political Science Review This content downloaded from 35.176.47.6 on Tue, 07 Aug 2018 08:47:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MILITANT DEMOCRACY AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS, II* KARL LOEWENSTEIN Amherst College II Some Illustrations of Militant Democracy. Before a more system- atic -account of anti-fascist legislation in Europe is undertaken, recent developments in several countries may be reviewed as illus- trating what militant democracy can achieve against subversive extremism when the will to survive is coupled with appropriate measures for combatting fascist techniques. 1. Finland: From the start, the Finnish Republic was particu- larly exposed to radicalism both from left and right. The newly established state was wholly devoid of previous experience in self- government, shaken by violent nationalism, bordered by bolshevik Russia, yet within the orbit of German imperialism; no other country seemed more predestined to go fascist. -

Nasjonal Samlings Ideologiske Utvikling 1933- 1937

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives “Ja takk, begge deler” - en analyse av Nasjonal Samlings ideologiske utvikling 1933- 1937 Robin Sande Masteroppgave Institutt for statsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 12. desember 2008 1 Forord Arbeidet med denne oppgaven tok til i mars 2008. Ideen fikk jeg imidlertid under et utvekslingsopphold i Berlin vinteren 2007/08. Fagene ”Politische Theorie und Geschichte am Beispiel der Weimarer Republik” og ”Politische Philosophien im Kontext des Nationalsozialismus” gjorde meg oppmerksom på at Nasjonal Samling må ha vært noe mer enn bare vertskap for tyske invasjonsstyrker. Hans Fredrik Dahls eminente biografi om Quisling: En fører blir til, vekket interessen ytterligere. Oppgaven kunne selvfølgelig vært mye mer omfattende. Det foreligger uendelige mengder litteratur både om liberalistisk elitisme og spesielt fascisme. Nasjonal Samlings historie kunne også vært behandlet mye mer inngående dersom jeg hadde hatt tid til et mer omfattende kildesøk. Dette gjelder også persongalleriet i Nasjonal Samling som absolutt hadde fortjent både mer tid og plass. Fremtredende personer som Johan B.Hjorth, Halldis Neegård Østbye, Gulbrand Lunde og Hans S.Jacobsen kunne hver for seg utgjort en masteravhandling alene. En videre diskusjon av de dominerende ideologiske tendensene i Nasjonal Samling kunne også vært meget intressant. Hvordan fortsatte den ideologiske utviklingen etter 1937 og frem til krigen, og hvordan fremsto Nasjonal Samling ideologisk etter den tyske invasjonen? Desverre er dette spørsmål som jeg, eller noen andre, må ha til gode. For å levere oppgaven på normert tid har det vært nødvendig å begrense omfanget av oppgaven. -

ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS in DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010

BEYOND THE DEMOCRATIC STATE: ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS IN DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science 2014 This thesis entitled: Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory written by Brian Carl Bernhardt has been approved for the Department of Political Science Steven Vanderheiden, Chair Michaele Ferguson David Mapel James Martel Alison Jaggar Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Bernhardt, Brian Carl (Ph.D., Political Science) Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory Thesis directed by Associate Professor Steven Vanderheiden Though democracy has achieved widespread global popularity, its meaning has become increasingly vacuous and citizen confidence in democratic governments continues to erode. I respond to this tension by articulating a vision of democracy inspired by anti-authoritarian theory and social movement practice. By anti-authoritarian, I mean a commitment to individual liberty, a skepticism toward centralized power, and a belief in the capacity of self-organization. This dissertation fosters a conversation between an anti-authoritarian perspective and democratic theory: What would an account of democracy that begins from these three commitments look like? In the first two chapters, I develop an anti-authoritarian account of freedom and power. -

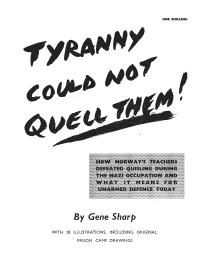

Tyranny Could Not Quell Them

ONE SHILLING , By Gene Sharp WITH 28 ILLUSTRATIONS , INCLUDING PRISON CAM ORIGINAL p DRAWINGS This pamphlet is issued by FOREWORD The Publications Committee of by Sigrid Lund ENE SHARP'S Peace News articles about the teachers' resistance in Norway are correct and G well-balanced, not exaggerating the heroism of the people involved, but showing them as quite human, and sometimes very uncertain in their reactions. They also give a right picture of the fact that the Norwegians were not pacifists and did not act out of a sure con viction about the way they had to go. Things hap pened in the way that they did because no other wa_v was open. On the other hand, when people acted, they The International Pacifist Weekly were steadfast and certain. Editorial and Publishing office: The fact that Quisling himself publicly stated that 3 Blackstock Road, London, N.4. the teachers' action had destroyed his plans is true, Tel: STAmford Hill 2262 and meant very much for further moves in the same Distribution office for U.S.A.: direction afterwards. 20 S. Twelfth Street, Philadelphia 7, Pa. The action of the parents, only briefly mentioned in this pamphlet, had a very important influence. It IF YOU BELIEVE IN reached almost every home in the country and every FREEDOM, JUSTICE one reacted spontaneously to it. AND PEACE INTRODUCTION you should regularly HE Norwegian teachers' resistance is one of the read this stimulating most widely known incidents of the Nazi occu paper T pation of Norway. There is much tender feeling concerning it, not because it shows outstanding heroism Special postal ofler or particularly dramatic event§, but because it shows to new reuders what happens where a section of ordinary citizens, very few of whom aspire to be heroes or pioneers of 8 ~e~~ 2s . -

Shirt Movements in Interwar Europe: a Totalitarian Fashion

Ler História | 72 | 2018 | pp. 151-173 SHIRT MOVEMENTS IN INTERWAR EUROPE: A TOTALITARIAN FASHION Juan Francisco Fuentes 151 Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain [email protected] The article deals with a typical phenomenon of the interwar period: the proliferation of socio-political movements expressing their “mood” and identity via a paramilitary uniform mainly composed of a coloured shirt. The analysis of 34 European shirt movements reveals some common features in terms of colour, ideology and chronology. Most of them were consistent with the logic and imagery of interwar totalitarianisms, which emerged as an alleged alternative to the decaying bourgeois society and its main political creation: the Parliamentary system. Unlike liBeral pluralism and its institutional expression, shirt move- ments embody the idea of a homogeneous community, based on a racial, social or cultural identity, and defend the streets, not the Ballot Boxes, as a new source of legitimacy. They perfectly mirror the overwhelming presence of the “brutalization of politics” (Mosse) and “senso-propaganda” (Chakhotin) in interwar Europe. Keywords: fascism, Nazism, totalitarianism, shirt movements, interwar period. Resumo (PT) no final do artigo. Résumé (FR) en fin d’article. “Of all items of clothing, shirts are the most important from a politi- cal point of view”, Eugenio Xammar, Berlin correspondent of the Spanish newspaper Ahora, wrote in 1932 (2005b, 74). The ability of the body and clothing to sublimate, to conceal or to express the intentions of a political actor was by no means a discovery of interwar totalitarianisms. Antoine de Baecque studied the political dimension of the body as metaphor in eighteenth-century France, paying special attention to the three specific func- tions that it played in the transition from the Ancien Régime to revolutionary France: embodying the state, narrating history and peopling ceremonies. -

Norwegian Volunteers of the Waffen SS Ebook Free Download

NORWEGIAN VOLUNTEERS OF THE WAFFEN SS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geir Brenden,Tommy Natedal | 528 pages | 13 Oct 2016 | Helion & Company | 9781910777879 | English | Solihull, United Kingdom Norwegian Volunteers of the Waffen SS PDF Book Only a handful of Germans were found in the battalion. He was an NS member, but he refused to politicize the unit, despite the wishes of some of his subordinates. The German 6. Blue Division [12]. On December 4 the Norwegians saw some of their toughest combat as 3. The regiment then turned over its remaining weapons to the other elements of Wiking. State police honor badge Facsimile signed of Jonas Lie The above citation was awarded for effort at the front. Nowhere did Norwegians serve in greater numbers than in the ranks of the Waffen-SS , but equal mention should also be made of those who served in the Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe, Heer and in the various auxiliary forces such as Organization Todt and even the Reichsarbeitdients. They were present in the town on October 14 when Finnish commandos attacked. Total: 20, [24]. There were many reasons why a Norwegian volunteer would want to risk his life by going to the front. Total: 80, [24]. The Norwegian Police formations in Sweden, or the Merchant Navy sailors are not included in this number. Hund also held the Wound Badge in Gold, and accumulated 64 close combat days by the end of the war, though he never received the Close Combat Clasp in Gold. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. At least two Norwegians met their fate at Stalingrad. -

Karl Loewenstein, John H. Herz, Militant Democracy and the Defense of the Democratic State

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Soldiers for Democracy: Karl Loewenstein, John H. Herz, Militant Democracy and the Defense of the Democratic State Ben Plache Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2995 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Ben Plache 2013 All Rights Reserved Soldiers for Democracy: Karl Loewenstein, John H. Herz, Militant Democracy and the Defense of the Democratic State A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Ben Plache Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2011 Director: Dr. Joseph Bendersky Professor, Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2013 Acknowledgements No scholarly work is an individual effort, and without the help of countless others this thesis would never have been completed. In particular I would like to thank Dr. Joseph Bendersky, my thesis advisor, for his time, his academic generosity and his commitment to education and scholarship. Without his guidance, this thesis, and my time in graduate school, would have been considerably different and undoubtedly poorer. I would like to also thank Dr. Timothy Thurber and Dr. Robert Godwin-Jones for generously agreeing to serve on my thesis committee. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk A

Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway By Dean N. Krouk A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair Professor Linda Rugg Professor Karin Sanders Professor Dorothy Hale Spring 2011 Abstract Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair This study examines selections from the work of three modernist writers who also supported Norwegian fascism and the Nazi occupation of Norway: Knut Hamsun (1859- 1952), winner of the 1920 Nobel Prize; Rolf Jacobsen (1907-1994), Norway’s major modernist poet; and Åsmund Sveen (1910-1963), a fascinating but forgotten expressionist figure. In literary studies, the connection between fascism and modernism is often associated with writers such as Ezra Pound or Filippo Marinetti. I look to a new national context and some less familiar figures to think through this international issue. Employing critical models from both literary and historical scholarship in modernist and fascist studies, I examine the unique and troubling intersection of aesthetics and politics presented by each figure. After establishing a conceptual framework in the first chapter, “Unsettling Modernity,” I devote a separate chapter to each author. Analyzing both literary publications and lesser-known documents, I describe how Hamsun’s early modernist fiction carnivalizes literary realism and bourgeois liberalism; how Sveen’s mystical and queer erotic vitalism overlapped with aspects of fascist discourse; and how Jacobsen imagined fascism as way to overcome modernity’s culture of nihilism. -

Nasjonal Samlings Bruk Av Ritualer Og Historiske Symboler 1933-45

PÅ NASJONAL GRUNN - Nasjonal Samlings bruk av ritualer og historiske symboler 1933-45 Masteroppgave i samtidshistorie ved Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie, Historisk filosofisk fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo, levert av Jimi Thaule, våren 2007 1 Forord Først og fremst vil jeg takke min veileder Øystein Sørensen, både for uvurderlig hjelp i skriveprosessen, hjelp med å finne det nødvendige materialet og for å ha hjulpet meg å finne den rette vinklingen på temaet. Jeg vil også takke Hans Fredrik Dahl som hjalp meg å finne litteratur om Nasjonal Samlings medievirksomhet og kultursyn. Jeg vil i tillegg takke Janne Waage Berset og Sissel Eun Kyung Aune for den støtten de har gitt meg, og for å ha lest gjennom oppgaven og kommet med spørsmål, tips og rettelser. En takk også til Radioarkivet ved NRK som har hjulpet meg med både stoff og oppmuntringer underveis. Jeg vil også nevne det slovenske industribandet Laibach, som gjennom sin "retrogardisme" vekket min interesse for autoritær symbolbruk og estetikk. Til slutt vil jeg også rette en stor takk til mine besteforeldre, Liv og Laurids Pedersen, som gjennom oppmuntringer og støtte gjennom mange år har gjort meg i stand til å gjennomføre studiene. Denne oppgaven hadde vært umulig å skrive uten dem. 2 Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Innledning 5 1.1 Tema og problemstilling 5 1.2 Metode og definisjoner 7 1.3 Hvorfor symboler og ritualer 13 1.4 Utvalg av møter 13 2 Historiesynet i Nasjonal Samling 15 2.1 Historiske røtter 15 2.2 Fascistiske myter 18 2.3 Nasjonal kontinuitet 23 2.4 Raseideologi 24 3 Perioden 1933-1940 26 3.1 Møter i perioden 26 3.2 Tidlige aktiviteter 27 3.3 Partiprogrammet fremlegges 29 3.4 Det 2.