Coleshill & the Settlements of the Chilterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPLORE and ENJOY in 2017/18 WIN! a Family Ticket to Bekonscot Model Village and Railway!

Outstanding Chilterns EXPLORE AND ENJOY IN 2017/18 WIN! A family ticket to Bekonscot Model Village and Railway! CHILTERNS BRAND NEW fiT GH to FOOD AND WALKING PROTECT the DRINK FESTIVAL CHILTERNS AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Outstanding l Seven family-friendly galleries l Shop with a wide range of gifts & souvenirs l Café stocking delicious local & Chilterns homemade produce EXPLORE AND ENJOY IN 2017/18 l Beautiful big garden open to AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY visitors l Interactive displays & Welcome to Outstanding Chilterns magazine – our annual educational activities for children www.chilternsaonb.org magazine which shines the spotlight on the very special Chilterns l Large events programme for The Chilterns AONB website has a all ages Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This edition is jam-packed with wealth of information on the area, l Nationally significant chair collection information and ideas on how to make the most of our beautiful including hundreds of downloadable countryside – explore and understand our landscapes; find out walks and cycling routes, an interac- tive map highlighting places to visit about ancient heritage; taste some of the foods and drinks produced and places to eat, a local events in the Chiltern Hills; and take part in our brand new 3-year Walking listing and lots of information on the Festival. We hope that you will discover all that the Chilterns has to special features of the Chilterns. offer and how you can get involved in helping us to protect it. Outstanding Chilterns is published Walking -

A Pretty Character Cottage in a Picturesque Village

A pretty character cottage in a picturesque village Belle Cottage, Turville, Henley-on-Thames, Buckinghamshire, RG9 6QX Freehold Sitting room • kitchen • shower room • two bedrooms landscaped garden • garage Directions These towns including the From either Henley-on- other regional centres of Thames or Marlow proceed on Oxford, High Wycombe and the A4155 towards Mill End. Reading offer comprehensive On approaching the hamlet of shopping, educational and Mill End turn north up the recreational facilities. There Hambleden valley signposted are a number of fine golf to Hambleden and Skirmett. courses in the area including Bypass Hambleden, proceed the Oxfordshire, Henley-on- through Skirmett and at Thames, Temple and Fingest turn left signposted to Huntercombe golf clubs. Turville. Follow the road into Racing may be enjoyed at the village just after The Bull & Ascot, Windsor, Newbury and Butcher pub keep to the left Kempton and there are and take the left turn into numerous boating facilities School Lane, Belle Cottage along the River Thames. The will be found on the right. area is well served for schools, with Buckinghamshire state Situation and grammar schools being Belle Cottage is centrally especially sought-after. located in the much sought- after Chiltern village of Description Turville, set back from the The front door opens into a village green, with the church spacious sitting room with a and the village pub sat at tiled floor with underfloor opposite ends. The village has heating and a open fireplace. been used for various films The kitchen has ample storage and TV programmes including with built in base and wall Vicar of Dibley, Chitty Chitty units as well as integrated Bang Bang, Midsomer appliances. -

London- West Midlands ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area Report CFA9 | Central Chilterns

LONDON-WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MIDLANDS LONDON-WEST | Vol 2 Vol LONDON- | Community Forum Area report Area Forum Community WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA9 | Central Chilterns | CFA9 | Central Chilterns November 2013 VOL VOL VOL ES 3.2.1.9 2 2 2 London- WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA9 | Central Chilterns November 2013 ES 3.2.1.9 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Details of how to obtain further copies are available from HS2 Ltd. Telephone: 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. CFA Report – Central Chilterns/No 9 | Contents Contents Contents i 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction to HS2 1 1.2 Purpose -

The Hidation of Buckinghamshire. Keith Bailey

THE HIDA TION OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE KEITH BAILEY In a pioneering paper Mr Bailey here subjects the Domesday data on the hidation of Buckinghamshire to a searching statistical analysis, using techniques never before applied to this county. His aim is not explain the hide, but to lay a foundation on which an explanation may be built; to isolate what is truly exceptional and therefore calls for further study. Although he disclaims any intention of going beyond analysis, his paper will surely advance our understanding of a very important feature of early English society. Part 1: Domesday Book 'What was the hide?' F. W. Maitland, in posing purposes for which it may be asked shows just 'this dreary old question' in his seminal study of how difficult it is to reach a consensus. It is Domesday Book,1 was right in saying that it almost, one might say, a Holy Grail, and sub• is in fact central to many of the great questions ject to many interpretations designed to fit this of early English history. He was echoed by or that theory about Anglo-Saxon society, its Baring a few years later, who wrote, 'the hide is origins and structures. grown somewhat tiresome, but we cannot well neglect it, for on no other Saxon institution In view of the large number of scholars who have we so many details, if we can but decipher have contributed to the subject, further discus• 2 them'. Many subsequent scholars have also sion might appear redundant. So it would be directed their attention to this subject: A. -

1 Buckinghamshire; a Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett

Buckinghamshire; A Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett 1 Chapter One: Origins to 1603 Although it is generally accepted that a truly national system of defence originated in England with the first militia statutes of 1558, there are continuities with earlier defence arrangements. One Edwardian historian claimed that the origins of the militia lay in the forces gathered by Cassivelaunus to oppose Caesar’s second landing in Britain in 54 BC. 1 This stretches credulity but military obligations or, more correctly, common burdens imposed on able bodied freemen do date from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the seventh and eight centuries. The supposedly resulting fyrd - simply the old English word for army - was not a genuine ‘nation in arms’ in the way suggested by Victorian historians but much more of a selective force of nobles and followers serving on a rotating basis. 2 The celebrated Burghal Hidage dating from the reign of Edward the Elder sometime after 914 AD but generally believed to reflect arrangements put in place by Alfred the Great does suggest significant ability to raise manpower at least among the West Saxons for the garrisoning of 30 fortified burghs on the basis of men levied from the acreage apportioned to each burgh. 3 In theory, it is possible that one in every four of all able-bodied men were liable for such garrison service. 4 Equally, while most surviving documentation dates only from 1 G. J. Hay, An Epitomised History of the Militia: The Military Lifebuoy, 54 BC to AD 1905 (London: United Services Gazette, 1905), 10. -

Home Counties North Regional Group

Home Counties North Regional Group FULL-DAY GEOLOGY FIELD TRIP Saturday 11 August 2018, 11.00 to 17.00 approx. Geology, hydrology, Iron Age geoarchaeology, and churches in the Parish of Cholesbury-cum-St Leonards, and Wendover Woods, Buckinghamshire. Led by John Wong FGS Meet at 11.00 outside the Full Moon public house, Cholesbury Lane, Hawridge Common, Cholesbury, HP5 2UH. Ordnance Survey grid reference SP936069. If you require a lift or can offer a lift, please let us know. Please bring hand lens and trowels. Lunches at Full Moon public house; afternoon refreshments in Wendover Woods (car parking in Wendover Woods is reasonable, pay on exit according to time duration of stay); you can bring a packed lunch. The Parish is on a high ridge, which extends for 4.5 miles (7.2km), rising to 760 feet AOD (230m) within the Chiltern Hills AONB. We shall see and/or discuss the following on this field trip – The history of the Full Moon public house and the Cholesbury Windmill. The local stratigraphy, structural geology, geomorphology, hydrology, drainage patterns, chalk springs and ponds. The local commemorative monument built of Buckinghamshire Puddingstones, and the petrology of local boundary stone. The geology of Hawridge, Cholesbury, Buckland Common, St Leonards and Wendover Woods. Stratigraphy in Wendover Woods reveals a full section of the Grey Chalk (former Lower Chalk) and White Chalk (former Middle Chalk and former Upper Chalk combined) Subgroups, the Melbourn Rock and Chalk Rock Formations. The origin, sedimentary structures and provenance of Holocene Red Clay and pebbly- clay in a disused pit, Pleistocene Clay-with-Flint in a disused pit and the archaeology of scattered strike flints. -

A MEETING of the PARISH COUNCIL on MONDAY 12Th OCTOBER 2020 at 8.00PM Via ZOOM

HAMBLEDEN PARISH COUNCIL n.0 Area in YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED TO ATTEND A MEETING OF THE PARISH COUNCIL ON MONDAY 12th OCTOBER 2020 at 8.00PM via ZOOM https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81985876382?pwd=RGUwTHk1Q1hqYzBMS3BYdFJ3eGJldz09 Meeting ID: 819 8587 6382 Password: 337589 Virtual Meeting Procedure Attached to Agenda – see Appendix 3 MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC AND PRESS ARE INVITED TO ATTEND AGENDA 1. Public Question Time – A period not to exceed 30 minutes, members of the public are permitted by the Chairman to speak only at this time 2. To receive any apologies for absence 3. Declaration of disclosable pecuniary and personal interests by Members relating to items on the agenda 4. To confirm and approve the minutes of the Ordinary meeting held 14th September 2020 via Zoom 5. Clerk and any Councillors if appropriate to report on matters arising and any updates from previous minutes which are not on the agenda 6. To consider any donations to village halls in the parish who are suffering financially due to constraints around Covid-19 7. Correspondence Report – see Appendix 1 (attached) for list of items and any action taken 8. To receive updates from any meetings attended since the previous ordinary meeting 9. To discuss the highway resurfacing in Hambleden – update to be provided if available 10. To consider approaching SSE about the undergrounding of electricity cables located in the parish 11. To consider altering the time of monthly parish council meetings to start earlier 12. To consider the next steps for the wildlife field in Ellery Rise, Frieth 13. -

Minutes 25-07-16 Page 1

Cholesbury-cum-St. Leonards final meeting minutes 25-07-16 Page 1 CHOLESBURY-CUM-ST LEONARDS PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of a Meeting of the Council held in St. Leonards Parish Hall on Monday 25th July 2016 at 8pm Present: Cllrs Allen, Brown, Joseph and Sanger. Also present: Mrs Lewis (Clerk), District Cllr Rose, County Cllr Birchley and three members of the public. 1975) To receive apologies for absence Cllrs Blomfield, Matthews and Minting. 1976) Matters arising None. 1977) To receive declarations of interest Cllr Allen declared an interest in planning application CH/2016/1329/KA as he is a member of the Board of Trustees of the land on which Hawridge and Cholesbury School is located. 1978) Questions from members of the public County Cllr Birchley reported that following communication and a meeting between Cllr Allen and Mark Averill (Head of Highways, BCC) to review the condition of the roads in the Parish, The Vale would be selected to be a priority road for resurfacing in the 2017/18 budget. The Parish Council thanked County Cllr Birchley for that decision. Cllr Brown questioned whether, following the decrease in funding and scope for project choices, the LAT forums were any longer relevant for small, rural Parish Councils. County Cllr Birchley replied that these were relevant concerns and would be raised at a County-wide level. District Cllr Rose reported that work on the Local Plan continues with the aim of undertaking another round of consultations in the autumn. Cllr Brown questioned whether there would be consultations at a Parish level and District Cllr Rose replied that, although this had not yet been decided, the comment would be taken forward. -

Land for Sale in Tring, Hertfordshire Land on West Leith, Tring, HP23 6JJ

v1.0 01582 788878 www.vantageland.co.uk Land for sale in Tring, Hertfordshire Land on West Leith, Tring, HP23 6JJ Grazing land for sale well situated close to Berkhamsted, Aylesbury, London and the A41 A desirable opportunity to purchase a self-enclosed parcel of attractive pasture land within the London commuter belt. Totalling just over 7 acres, the land is for sale as a whole or in just 3 lots and is suitable for a variety of amenity, recreational or other uses (STPP). Each lot has been marked out by a professional surveyor and has been fenced. The site enjoys extensive road frontage and benefits from excellent access via a secure double-gated entrance that is set back from the road. The land is situated on the southern edge of Tring, just a 15 minute walk from its bustling High Street which offers an extensive mix of shops, cafes, bars and restaurants. It is also superbly located for road and rail links into London. House prices in Tring are 69% above the national average reflecting the desirability of the area as a place to live and own property – including land. Indeed, the local council states that land for “small-scale ‘hobby farming’ and the demand for horse paddocks and ménages is on the increase, particularly on the urban fringe”. POSTCODE OF NEAREST PROPERTY: HP23 6JJ © COLLINS BARTHOLOMEW 2003 Travel & Transport The land lies in the historic market town of Tring in west Hertfordshire, on the border with 0.8 miles to the A41 Buckinghamshire. Its pretty Victorian High Street 2.5 miles to Tring Train Station * offers an extensive mix of independently run 11.2 miles to the M1 (junction 8) shops, cafes, bars and restaurants. -

Dacorum Borough Council

case study Rocket® Dacorum Borough Council Finding and Capturing the Golden Thread Dacorum is an area of 212 square kilometers situated in West Hertfordshire that includes the towns of Hemel Hempstead, Berkhamsted, Tring, the villages of Bovingdon, Kings Langley, and Markyate, and 12 smaller settlements. 50% of the area is Green Belt and around 18% of the borough’s 60,000 homes are owned by the council. The Council is improving in key priority areas, and the overall rate of improvement is above average compared with other District Councils. Situation The challenge for the borough’s business improvement team was to be able to show the Dacorum community and council members that that their priorities were being met, and to demonstrate to auditors that the organization was managing its business and performance eectively. One of the biggest diculties was to show the linkages between the top-level priorities and the everyday activities of the council. This is commonly alluded to by the Audit Commission as “The Golden Thread.” In order to improve and move to a Portfolio Management approach, where all projects and programs clearly contribute to the Council’s strategic priorities, Dacorum Borough Council had to be able to demonstrate the golden thread process, which included: • setting clear priorities – what we all have to achieve • citizen needs – what our communities need and expect from us • sound nancial control – spending resources wisely and forecasting for the future • improving service delivery – better value for money for citizens • sta engagement and development – ensuring sta have the right skills and opportunities • tracking our progress – celebrating success and reacting quickly where necessary Solution One of the key outcomes to be delivered from this appointment was to improve performance planning and management. -

Chiltern Way Accommodation 2009

CHILTERN WAY ACCOMMODATION 2018 VILLAGE/TOWN ACCOMMODATION WEBSITE/TELEPHONE HEMEL HEMPSTEAD Boxmoor Boxmoor Lodge Hotel, London Road www.boxmoorlodge.co.uk Boxmoor, Hemel Hempstead, Herts, 01442 230770 HP1 2RA. (500 yds) Best Western Watermill Hotel, London www.hotelwatermill.co.uk Road, Bourne End, Hemel Hempstead, 01442 349 955 Herts, HP1 2RJ. (2 miles) Olde Kings Arms www.phcompany.com 41 High Street, Hemel Hempstead 01442 255348 HP1 3AF (1.25 miles) Flaunden Two Brewers, The Common, www.chefandbrewer.com Chipperfield, Kings Langley, Herts, 01923 265266 WD4 9BS. (1.5 miles) CHENIES Chenies Bedford Arms Hotel, Chenies Village, www.bedfordarms.co.uk Rickmansworth, Herts, WD3 6 EQ 01923 283301 (220 yds) De Vere Venues Latimer Place www.phcompany.com Latimer, Chesham, Bucks, HP5 1UG 0871 222 4810 (1.5 miles) Chalfont Coppermill, 16 Kings Road, Chalfont St www.chalfontbedbreakfast.co.uk St Giles Giles, Bucks, HP8 4HS. (500 yds) 01494 581046 Ivy House Pub, London Road, Chalfont www.ivyhousechalfontstgiles.co.uk St Giles, Bucks, HP8 4RS. (2 miles) 01494 872184 White Hart Inn, Three Households, www.oldenglishinns.co.uk Chalfont St Giles, Bucks, HP8 4LP. 01494 872441 (500 yds) Jordans Youth Hostel, Welders Lane, www.yha.org.uk Jordans, Beaconsfield, Bucks, HP9 2SN. 0345 371 9523 (2 miles) Highclere Farm Camping, Newbarn Lane, www.highclerefarmpark.co.uk Seer Green, Beaconsfield, Bucks, HP9 2QZ 01494 874505 (600 yds) START OF BERKSHIRE LOOP 1 Beaconsfield The White Hart Hotel, Aylesbury End www.vintageinn.co.uk Beaconsfield, Bucks, HP9 1LW 01494 671211 (1.5 miles) Monique’s B&B, 1 Amersham Road www.beaconsfieldbedandbreakfast. -

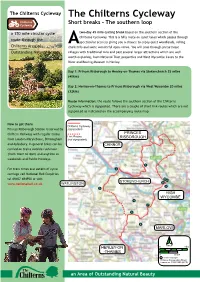

The Chilterns Cycleway the Chilterns Cycleway Chilterns Short Breaks - the Southern Loop Cycleway

The Chilterns Cycleway The Chilterns Cycleway Chilterns Short breaks - The southern loop Cycleway a 170 mile circular cycle two-day 45 mile cycling break based on the southern section of the Chilterns Cycleway. This is a hilly route on quiet lanes which passes through route through the Aspectacular scenery giving you a chance to enjoy quiet woodlands, rolling Chilterns Area of chalk hills and some wonderful open views. You will pass through picturesque Outstanding Natural Beauty villages with traditional inns and past several larger attractions which are well worth exploring, from National Trust properties and West Wycombe Caves to the River and Rowing Museum in Henley. Day 1: Princes Risborough to Henley-on-Thames via Stokenchurch 25 miles (40km) Day 2: Henley-on-Thames to Princes Risborough via West Wycombe 20 miles (32km) Route information: the route follows the southern section of the Chilterns Cycleway which is signposted. There are a couple of short link-routes which are not signposted as indicated on the accompanying route map. How to get there Chilterns Cycleway Princes Risborough Station is served by (signposted) Chiltern Railways with regular trains PRINCES Link Routes RISBOROUGH from London Marylebone, Birmingham (not signposted) and Aylesbury. In general bikes can be CHINNOR carried on trains outside rush hour (from 10am to 4pm) and anytime at weekends and Public Holidays. 1 For train times and details of cycle 2 carriage call National Rail Enquiries tel 08457 484950 or visit 11 STOKENCHURCH 10 www.nationalrail.co.uk WATLINGTON 8 9 3 HIGH WYCOMBE 4 7 5 6 MARLOW north HENLEY-ON 0 5km -THAMES 0 2mile c Crown copyright.