THE BOMB MAKER WHO DOUBTED Reviewed by Mikhail Novikov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

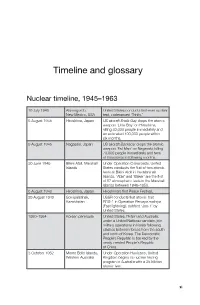

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

People and Things

People and things Geoff Manning for his contributions Dirac Medal to physics applications at the Lab oratory, particularly in high energy At the recent symposium on 'Per physics, computing and the new spectives in Particle Physics' at Spallation Neutron Source. The the International Centre for Theo Rutherford Prize goes to Alan Ast- retical Physics, Trieste, ICTP Direc bury of Victoria, Canada, former tor Abdus Sa la m presided over co-spokesman of the UA 1 experi the first award ceremony for the ment at CERN. Institute's Dirac Medals. Although Philip Anderson (Princeton) and expected, Yakov Zeldovich of Abdus Sa la m (Imperial College Moscow's Institute of Space Re London and the International search was not able to attend to Centre for Theoretical Physics, receive his medal. Edward Witten Trieste) have been elected Hono of Princeton received his gold me rary Fellows of the Institute. dal alone from Antonino Zichichi on behalf of the Award Committee. Third World Prizes The 1985 Third World Academy UK Institute of Physics Awards of Sciences Physics Prize has been awarded to E. C. G. Sudarshan The Guthrie Prize and Medal of the from India for his fundamental con UK Institute of Physics this year tributions to the understanding of goes to Sir Denys Wilkinson of the weak nuclear force, in particu Sussex for his many contributions lar for his work with R. Marshak to nuclear physics. The Institute's on the theory which incorporates Glazebrook Prize goes to Ruther its parity (left/right symmetry) Friends and colleagues recently ford Appleton Laboratory director structure. -

Hawking Radiation and the Expansion of the Universe

Hawking radiation and the expansion of the universe 1 2, 3 Yoav Weinstein , Eran Sinbar *, and Gabriel Sinbar 1 DIR Technologies, Matam Towers 3, 6F, P.O.Box 15129, Haifa, 319050, Israel 2 DIR Technologies, Matam Towers 3, 6F, P.O.Box 15129, Haifa, 3190501, Israel 3 RAFAEL advanced defense systems ltd., POB 2250(19), Haifa, 3102102, Israel * Corresponding author: Eran Sinbar, Ela 13, Shorashim, Misgav, 2016400, Israel, Telephone: +972-4-9028428, Mobile phone: +972-523-713024, Email: [email protected] ABSTRUCT Based on Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle it is concluded that the vacuum is filed with matter and anti-matter virtual pairs (“quantum foam”) that pop out and annihilate back in a very short period of time. When this quantum effects happen just outside the "event horizon" of a black hole, there is a chance that one of these virtual particles will pass through the event horizon and be sucked forever into the black hole while its partner virtual particle remains outside the event horizon free to float in space as a real particle (Hawking Radiation). In our previous work [1], we claim that antimatter particle has anti-gravity characteristic, therefore, we claim that during the Hawking radiation procedure, virtual matter particles have much larger chance to be sucked by gravity into the black hole then its copartner the anti-matter (anti-gravity) virtual particle. This leads us to the conclusion that hawking radiation is a significant source for continuous generation of mostly new anti-matter particles, spread in deep space, contributing to the expansion of space through their anti-gravity characteristic. -

Frequency of Hawking Radiation of Black Holes

International Journal of Astrophysics and Space Science 2013; 1(4): 45-51 Published online October 30, 2013 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijass) doi: 10.11648/j.ijass.20130104.15 Frequency of Hawking radiation of black holes Dipo Mahto 1, Brajesh Kumar Jha 2, Krishna Murari Singh 1, Kamala Parhi 3 1Dept. of Physics, Marwari College, T.M.B.U. Bhagalpur-812007, India 2Deptartment of Physics, L.N.M.U. Darbhanga, India 3Dept. of Mathematics, Marwari College, T.M.B.U. Bhagalpur-812007, India Email address: [email protected](D. Mahto), [email protected](B. K. Jha), [email protected](K. M. Singh), [email protected] (K . Parhi) To cite this article: Dipo Mahto, Brajesh Kumar Jha, Krishna Murari Singh, Kamala Parhi. Frequency of Hawking Radiation of Black Holes. International Journal of Astrophysics and Space Science. Vol. 1, No. 4, 2013, pp. 45-51. doi: 10.11648/j.ijass.20130104.15 Abstract: In the present research work, we calculate the frequencies of Hawking radiations emitted from different test black holes existing in X-ray binaries (XRBs) and active galactic nuclei (AGN) by utilizing the proposed formula for the 8.037× 10 33 kg frequency of Hawking radiation f= Hz and show that these frequencies of Hawking radiations may be the M components of electromagnetic spectrum and gravitational waves. We also extend this work to convert the frequency of Hawking radiation in terms of the mass of the sun ( M ⊙ ) and then of Chandrasekhar limit ( M ch ), which is the largest unit of mass. Keywords: Electromagnetic Spectrum, Hawking Radiation, XRBs and AGN Starobinsky showed him that according to the quantum 1. -

The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952

Igniting The Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES Approved: Joseph C. Pitt, Chair Richard M. Burian Burton I. Kaufman Albert E. Moyer Richard Hirsh June 23, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Nuclear Weapons, Computing, Physics, Los Alamos National Laboratory Igniting the Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Committee Chairman: Joseph C. Pitt Science and Technology Studies (ABSTRACT) The American system of nuclear weapons research and development was conceived and developed not as a result of technological determinism, but by a number of individual architects who promoted the growth of this large technologically-based complex. While some of the technological artifacts of this system, such as the fission weapons used in World War II, have been the subject of many historical studies, their technical successors -- fusion (or hydrogen) devices -- are representative of the largely unstudied highly secret realms of nuclear weapons science and engineering. In the postwar period a small number of Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory’s staff and affiliates were responsible for theoretical work on fusion weapons, yet the program was subject to both the provisions and constraints of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, of which Los Alamos was a part. The Commission leadership’s struggle to establish a mission for its network of laboratories, least of all to keep them operating, affected Los Alamos’s leaders’ decisions as to the course of weapons design and development projects. -

Interview with Alexander Ivanovich Pavlovskii

Interview with Alexander Ivanovich Pavlovskii Interview with Alexander Ivanovich Pavlovskii t the end of the intense week-long meeting at Los Alamos in November 1992 among scientists from Arzamas-16, Los A Alamos, and Sandia, we met with the head of the Russian delegation, Alexander I. Pavlovskii, to talk about his expe- riences as a nuclear-weapons scientist in the former Soviet Union. Pavlovskii had been a protegé of Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov. At the time of our conversation, he was Deputy Chief Scientist and Head of the Fundamental and Ap- plied Physics Department of the All-Russia Scientific Research In- stitute of Experimental Physics at Arzamas-16, Russia. Two translators were present: Elena Panevkina, who was by Pavlovskii’s side at all meetings with non-Russian speaking scientists, and Eugene Kutyreff from the Laboratory’s International Technology Division. We thank both of them for their patience and endurance. Just as we were preparing to send this interview to Pavlovskii for his review, we learned of his sudden death on February 12, 1993. We were honored to have met him and moved by the candor and depth of feeling he expressed during our interview. Many scientists at Los Alamos knew Pavlovskii well, and we hope they will find this interview a fitting memorial to an exceptional man. 82 Los Alamos Science Number 21 1993 Interview with Alexander Ivanovich Pavlovskii Los Alamos Science: Tell us how different. Sinelnikov didn’t really environment in the world, this type you got into science and how you want me to leave the Physicotechni- of weapon was absolutely necessary. -

News and Views Yulii Khariton (1904-96)

news and views Obituary design was detonated in 1951. The first Yulii Khariton (1904-96) Soviet hydrogen bomb was tested in August 1953, and the first two-stage Physicist, instrumental in thermonuclear weapon in November 1955. Khariton was in many ways a surprising developing Soviet nuclear choice as chief designer of nuclear weapons. weapons His two years in the West made him politically suspect. So, too, did the fact that Yuill Borisovich Khariton, who died on I9 his parents lived abroad: his mother December last year at the age of 92, was a emigrated to Palestine from Germany in the key figure in the Soviet nuclear weapons 1930s; and his father, who lived in Riga programme. For over 40 years he was before the war, was arrested and shot when scientific director ofArzamas-I6, the the Red Army occupied the Baltic states in Soviet equivalent of Los Alamos. 1940. Yet Khariton remained untouched Khariton was born into a literary and even by the anti-semitic campaign ofthe late artistic family in St Petersburg in I904, and 1940s. He met Stalin only once, but he had to throughout his life retained the manners work closely with Lavrentii Beria, the head and interests of a Russian intellectual. He ofthe secret police, whom he found efficient studied physics at the Polytechnical and correct in his dealings with scientists. Institute, and was invited by Nikolai Khariton remained scientific director of Semenov (who received the Nobel prize for Arzamas-16 until1992. His approach to chemistry in I956 for his work on chemical design and development was careful and chain reactions) to do research at the thorough: "We have to know ten times Leningrad Physicotechnical Institute, the more than we are doing" was his motto. -

The Dark Energy of the Universe the Dark Energy of the Universe

The dark energy of the universe The dark energy of the universe Jim Cline, McGill University Astro night, 21 Jan., 2016 image: bornscientist.com J.Cline, McGill U. – p. 1 Dark Energy in a nutshell In 1998, astronomers presented evidence that the primary energy density of the universe is not from particles or radiation, but of empty space—the vacuum. Einstein had predicted it 80 years earlier, but few people believed this prediction, not even Einstein himself. Many scientists were surprised, and the discovery was considered revolutionary. Since then, thousands of papers have been written on the subject, many speculating on the detailed properties of the dark energy. The fundamental origin of dark energy is the subject of intense controversy and debate amongst theorists. J.Cline, McGill U. – p. 2 Outline History of the dark energy • Theory of cosmological expansion • The observational evidence for dark energy • What could it be? • Upcoming observations • The theoretical crisis !!! • J.Cline, McGill U. – p. 3 Albert Einstein invents dark energy, 1917 Two years after introducing general relativity (1915), Einstein looks for cosmological solutions of his equations. No static solution exists, contrary to observed universe at that time He adds new term to his equations to allow for static universe, the cosmological constant λ: J.Cline, McGill U. – p. 4 Einstein’s static universe This universe is a three-sphere with radius R and uniform mass density of stars ρ (mass per volume). mechanical analogy potential energy R R By demanding special relationships between λ, ρ and R, λ = κρ/2 = 1/R2, a static solution can be found. -

J. Robert Oppenheimer and His Colleagues Opposed Development of the Hydrogen Bomb

the years immediately following World War II, the United States was the only nation with the atomic bomb. Its strategic dominance, however, rested on a thin veneer of actual military capability. As late as 1947, the US did not have any atomic bombs assembled and ready for use. The Atomic Energy Commission, which held custody, was to work up the bombs and transfer them to the Air Force if and when they were needed. The Air Force had only a few airplanes, “Silver Plate” B-29s, that could deliver the bomb, and few trained crews. The leading atomic scientists who developed the atomic bomb during the war had left the Los Alamos weapons laboratory in New Mexico. Most of them were opposed to further military development of atomic energy. The US in 1946 proposed international control of atomic weapons. The offer to the United Nations fell through because the Soviets demanded the US eliminate its nuclear weapons as a precondition to agreement. J. Robert Oppenheimer and his colleagues opposed development of the hydrogen bomb. The fi rst thermonuclear explosion was the “Ivy Mike” test at Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacifi c in 1952. The fi reball was three miles wide and vaporized the coral islet on which the shot occurred. 62 AIR FORCE Magazine / October 2015 The concept for a far more powerful nuclear weapon—the hydrogen bomb, called the “Super” by the atomic scientists—had been around for some time. Few outside of the scientific community knew about it, and except for a few scattered advocates, there was almost no inter- est in pursuing it. -

Stalin and the Hydrogen Bomb 49 a Bomb Seemed Completely Unreal

48 The Short Millennium? Stalin and the The hydrogen bomb: the beginning of the project Hydrogen The atomic bomb was the artificial creation of Bomb man. Plutonium does not exist in nature, and uranium-235 does not accumulate anywhere in the quantities which produce the chain reaction of its almost instant fission. The idea of the hydrogen bomb was based on the physical phenomenon which is most widespread in the universe: nuclear synthesis, the formation of nuclear atoms of the heavier elements at the expense of the fusion of the nuclei of light elements. Almost all the elements of the earth’s Zhores A. Medvedev crust arose in this way. At high temperatures, of the order of hundreds of millions of degrees, the kinetic energy of the atoms of the light elements becomes so high that, colliding with themselves, they are able to ‘fuse’, forming In our last issue, in his nuclei of heavier elements. Hundreds of article entitled ‘Stalin and thousands times more energy is released at the the atomic bomb’, Zhores nuclear synthesis than at the fission of the Medvedev shed new light heavy atoms. Interest in the problem of nuclear on the beginnings of the fusion arose in the 1930s, especially after Hans nuclear era in the Soviet A. Bethe, the German physicist who, in 1934, Union. Now, he turns to the emigrated to the United States, developed the race to build the Soviet theory of the production of energy of the stars, Union’s thermonuclear or including the sun. According to this theory, hydrogen bomb. This article which was sufficiently well confirmed at the also contains much new time, the energy of the stars arose in the basic information. -

Cold War and Proliferation

Cold War and Proliferation After Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki and the defeat of Germany, the US believed to be in the absolute lead in nuclear weapon technology, US even supported Baruch plan for a short period of six months. But proliferation had started even before the Trinity test and developed rapidly to a whole set of Nuclear Powers over the following decades Spies and Proliferation At Potsdam conference 1945 Stalin was informed about US bomb project. Efficient Russian spy system in US had been established based on US communist cells and emigrant sympathies and worries about single dominant political and military power. Klaus Fuchs, German born British physicist, part of the British Collaboration at the Manhattan project passed information about Manhattan project and bomb development and design Plans to Russia. Arrested in 1949 in Britain and convicted to 14 years of prison. He served 9 years - returned to East Germany as Director of the Rossendorf Nuclear Research center. Fuchs case cause panic and enhanced security in US in times of cold war, fired by McCarthy propaganda. Numerous subsequent arrests and trials culminating in Rosenberg case! The second race for the bomb Start of soviet weapons program Program was ordered by Stalin in 1943 after being informed about US efforts. The administrative head of the program was Lavrenti Beria. Scientific director was Igor Kurchatov, Who headed the Russian nuclear research program and built the first Russian cyclotron in 1934. Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria (1899-1953), Soviet politician and police chief, is remembered chiefly as the executor of Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s His period of greatest power was during and after WW-II.