The Oxford Handbook of the History of Modern Cosmology Edited by Helge Kragh and Malcolm S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocabulary of Definitions : P

Service bibliothèque Catalogue historique de la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice Source : Monographie de l’Observatoire de Nice / Charles Garnier, 1892. Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur Février 2012 Présentation << On trouve… à l’Ouest … la bibliothèque avec ses six mille deux cents volumes et ses trentes journaux ou recueils périodiques…. >> (Façade principale de la Bibliothèque / Phot. attribuée à Michaud A. – 188? - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) C’est en ces termes qu’Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin décrivait la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice en 1899 dans l’introduction du tome 1 des Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice 1. Un catalogue des revues et ouvrages 2 classé par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs et de lieux décrivait le fonds historique de la bibliothèque. 1 Introduction, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. XIV 2 Catalogue de la bibliothèque, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. 1 Le présent document est une version remaniée, complétée et enrichie de ce catalogue. (Bibliothèque, vue de l’intérieur par le photogr. Jean Giletta, 191?. - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) Chaque référence est reproduite à l’identique. Elle est complétée par une notice bibliographique et éventuellement par un lien électronique sur la version numérisée. Les titres et documents non encore identifiés sont signalés en italique. Un index des auteurs et des titres de revues termine le document. -

Seeing in a New Light

Seeing in a New Light I I Teacher's Guide With ActiVities _ jo I Acknowledgements The Astro-1 Teacher's Guide, "Seeing in a New Light," was prepared by Essex Corporation of Huntsville, AL, for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration with the guidance, support, and cooperation of many individuals and groups. NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC Office of Space Science and Applications Flight Systems Division Astrophysics Division Office of External Affairs Educational Affairs Division Office of Communications Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL Payload Projects Office Public Affairs Office Goddard Space Flight Center;_eenbelt, MD Explorers and Attached Payload Projects Laboratory for Astronomy and Solar Physics Public Affairs Office Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX Astronaut Office Scientists, teachers, and others who gave their time and creativity in recognition of the importance of the space program in inspiring and educating students. Special thanks to the Astro Team and to Essex Corporation for their creativity in making this document a reality. Astro-1 Teacher's Guide With Activities Seeing in a New Light January 1990 EP274 NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration Astro-1 Teacher's Guide With Activities Seeing in a New Light CONTENTS o,, Preface ..................................................................................... ttt Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Instructions for Using the Teacher's Guide ............................... 2 Seeing -

Fred L. Whipple Oral History Interviews, 1976

Fred L. Whipple Oral History Interviews, 1976 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Fred L. Whipple Oral History Interviews https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217688 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Fred L. Whipple Oral History Interviews Identifier: Record Unit 9520 Date: 1976 Extent: 4 audiotapes (Reference copies). Creator:: Whipple, Fred L. (Fred Lawrence), 1906-2004, interviewee Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian -

2016-2017 Year Book Www

1 2016-2017 YEAR BOOK WWW. C A R N E G I E S C I E N C E . E D U Department of Embryology 3520 San Martin Dr. / Baltimore, MD 21218 410.246.3001 Geophysical Laboratory 5251 Broad Branch Rd., N.W. / Washington, DC 20015-1305 202.478.8900 Department of Global Ecology 260 Panama St. / Stanford, CA 94305-4101 650.462.1047 The Carnegie Observatories 813 Santa Barbara St. / Pasadena, CA 91101-1292 626.577.1122 Las Campanas Observatory Casilla 601 / La Serena, Chile Department of Plant Biology 260 Panama St. / Stanford, CA 94305-4101 650.325.1521 Department of Terrestrial Magnetism 5241 Broad Branch Rd., N.W. / Washington, DC 20015-1305 202.478.8820 Office of Administration 1530 P St., N.W. / Washington, DC 20005-1910 202.387.6400 2 0 1 6 - 2 0 1 7 Y E A R B O O K The President’s Report July 1, 2016 - June 30, 2017 C A R N E G I E I N S T I T U T I O N F O R S C I E N C E Former Presidents Daniel C. Gilman, 1902–1904 Robert S. Woodward, 1904–1920 John C. Merriam, 1921–1938 Vannevar Bush, 1939–1955 Caryl P. Haskins, 1956–1971 Philip H. Abelson, 1971–1978 James D. Ebert, 1978–1987 Edward E. David, Jr. (Acting President, 1987–1988) Maxine F. Singer, 1988–2002 Michael E. Gellert (Acting President, Jan.–April 2003) Richard A. Meserve, 2003–2014 Former Trustees Philip H. Abelson, 1978–2004 Patrick E. -

People and Things

People and things Geoff Manning for his contributions Dirac Medal to physics applications at the Lab oratory, particularly in high energy At the recent symposium on 'Per physics, computing and the new spectives in Particle Physics' at Spallation Neutron Source. The the International Centre for Theo Rutherford Prize goes to Alan Ast- retical Physics, Trieste, ICTP Direc bury of Victoria, Canada, former tor Abdus Sa la m presided over co-spokesman of the UA 1 experi the first award ceremony for the ment at CERN. Institute's Dirac Medals. Although Philip Anderson (Princeton) and expected, Yakov Zeldovich of Abdus Sa la m (Imperial College Moscow's Institute of Space Re London and the International search was not able to attend to Centre for Theoretical Physics, receive his medal. Edward Witten Trieste) have been elected Hono of Princeton received his gold me rary Fellows of the Institute. dal alone from Antonino Zichichi on behalf of the Award Committee. Third World Prizes The 1985 Third World Academy UK Institute of Physics Awards of Sciences Physics Prize has been awarded to E. C. G. Sudarshan The Guthrie Prize and Medal of the from India for his fundamental con UK Institute of Physics this year tributions to the understanding of goes to Sir Denys Wilkinson of the weak nuclear force, in particu Sussex for his many contributions lar for his work with R. Marshak to nuclear physics. The Institute's on the theory which incorporates Glazebrook Prize goes to Ruther its parity (left/right symmetry) Friends and colleagues recently ford Appleton Laboratory director structure. -

Active Galactic Nuclei and Their Neighbours

CCD Photometric Observations of Active Galactic Nuclei and their Neighbours by Traianou Efthalia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ptychion (Physics) in Aristotle University of Thessaloniki September 2016 Supervisor: Manolis Plionis, Professor To my loved ones Many thanks to: Manolis Plionis for accepting to be my thesis adviser. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ii LIST OF FIGURES ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: v LIST OF TABLES :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ix LIST OF APPENDICES :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: x ABSTRACT ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: xi CHAPTER I. Introduction .............................. 1 II. Active Galactic Nuclei ........................ 4 2.1 Early History of AGN’s ..................... 4 2.2 AGN Phenomenology ...................... 7 2.2.1 Seyfert Galaxies ................... 7 2.2.2 Low Ionization Nuclear Emission-Line Regions(LINERS) 10 2.2.3 ULIRGS ........................ 11 2.2.4 Radio Galaxies .................... 12 2.2.5 Quasars or QSO’s ................... 14 2.2.6 Blazars ......................... 15 2.3 The Unification Paradigm .................... 16 2.4 Beyond the Unified Model ................... 18 III. Research Goal and Methodology ................. 21 3.1 Torus ............................... 21 3.2 Ha Balmer Line ......................... 23 3.3 Galaxy-Galaxy Interactions ................... 25 3.4 Our Aim ............................. 27 iii IV. Observations .............................. 29 4.1 The Telescope -

Table of Contents

AAS Newsletter September/October 2012, Issue 166 - Published for the Members of the American Astronomical Society Table of Contents 2 President’s Column 17 Committee on the Status of Women in 4 From the Executive Office Astronomy 5 What Makes an Astronomy Story 18 News from NSF Division of Astronomical Newsworthy? Sciences (AST) 6 Journals Update 20 JWST Update 9 Secretary's Corner 21 HAD News 9 Council Actions 21 Honored Elsewhere 10 The AAS Heeds the Call of the Wild 22 Announcements 16 Committee on Employment 23 Calendar of Events 25 Washington News A A S American Astronomical Society AAS Officers President's Column David J. Helfand, President Debra M. Elmegreen, Past President David J. Helfand, [email protected] Nicholas B. Suntzeff, Vice-President Edward B. Churchwell, Vice-President Paula Szkody, Vice-President Hervey (Peter) Stockman, Treasurer G. Fritz Benedict, Secretary Anne P. Cowley, Publications Board Chair Edward E. Prather, Education Officer At 1:32AM Eastern time on 6 Councilors August, the Mars Science Laboratory Bruce Balick Nancy S. Brickhouse and its charmingly named rover, Eileen D. Friel Curiosity, executed a perfect landing Edward F. Guinan Todd J. Henry in Gale Crater. President Obama Steven D. Kawaler called the highly complex landing Patricia Knezek Robert Mathieu procedure “an unprecedented feat of Angela Speck technology that will stand as a point Executive Office Staff of pride far into the future.” While Kevin B. Marvel, Executive Officer we certainly hope Curiosity’s lifetime Tracy Beale, Registrar & Meeting Coordinator Chris Biemesderfer, Director of Publishing on Mars is a long one, we must all Sherri Brown, Membership Services continue to make the case that we Coordinator Kelly E. -

How Supernovae Became the Basis of Observational Cosmology

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 19(2), 203–215 (2016). HOW SUPERNOVAE BECAME THE BASIS OF OBSERVATIONAL COSMOLOGY Maria Victorovna Pruzhinskaya Laboratoire de Physique Corpusculaire, Université Clermont Auvergne, Université Blaise Pascal, CNRS/IN2P3, Clermont-Ferrand, France; and Sternberg Astronomical Institute of Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991, Moscow, Universitetsky prospect 13, Russia. Email: [email protected] and Sergey Mikhailovich Lisakov Laboratoire Lagrange, UMR7293, Université Nice Sophia-Antipolis, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, Boulevard de l'Observatoire, CS 34229, Nice, France. Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper is dedicated to the discovery of one of the most important relationships in supernova cosmology—the relation between the peak luminosity of Type Ia supernovae and their luminosity decline rate after maximum light. The history of this relationship is quite long and interesting. The relationship was independently discovered by the American statistician and astronomer Bert Woodard Rust and the Soviet astronomer Yury Pavlovich Pskovskii in the 1970s. Using a limited sample of Type I supernovae they were able to show that the brighter the supernova is, the slower its luminosity declines after maximum. Only with the appearance of CCD cameras could Mark Phillips re-inspect this relationship on a new level of accuracy using a better sample of supernovae. His investigations confirmed the idea proposed earlier by Rust and Pskovskii. Keywords: supernovae, Pskovskii, Rust 1 INTRODUCTION However, from the moment that Albert Einstein (1879–1955; Whittaker, 1955) introduced into the In 1998–1999 astronomers discovered the accel- equations of the General Theory of Relativity a erating expansion of the Universe through the cosmological constant until the discovery of the observations of very far standard candles (for accelerating expansion of the Universe, nearly a review see Lipunov and Chernin, 2012). -

The Scientific Legacy of Fred Hoyle Edited by Douglas Gough Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521824486 - The Scientific Legacy of Fred Hoyle Edited by Douglas Gough Frontmatter More information The Scientific Legacy of Fred Hoyle Fred Hoyle was a remarkable scientist, and made an immense contribution to solving many important problems in astronomy. Several of his obituaries commented that he had made more influence on the course of astrophysics and cosmology in the second half of the twentieth century than any other person. This book is based on a meeting that was held in recognition of his work, and contains chapters by many of Hoyle’s scientific collaborators. Each chapter reviews an aspect of Fred Hoyle’s work; many of the subjects he tackled are still areas of hot debate and active research. The chapters are not confined to the discoveries of Hoyle’s own time, but also discuss up-to-date research that has grown out of his pioneering work, particularly on the interstellar medium and star formation, the structure of stars, nucleosynthesis, gravitational dynamics, and cosmology. This wide-ranging overview will be valuable to established researchers in astrophysics and cosmology, and also to professional historians of science. Douglas Gough is the Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics, and Director of the Institute of Astronomy, at the University of Cambridge. He is an honorary professor at the University of London, an adjunct fellow at the University of Colorado, and a visiting professor of physics at Stanford University. His main research interest is the internal dynamics of stars. © Cambridge University -

Astrophysics in 2006 3

ASTROPHYSICS IN 2006 Virginia Trimble1, Markus J. Aschwanden2, and Carl J. Hansen3 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575, Las Cumbres Observatory, Santa Barbara, CA: ([email protected]) 2 Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Organization ADBS, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304: ([email protected]) 3 JILA, Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder CO 80309: ([email protected]) Received ... : accepted ... Abstract. The fastest pulsar and the slowest nova; the oldest galaxies and the youngest stars; the weirdest life forms and the commonest dwarfs; the highest energy particles and the lowest energy photons. These were some of the extremes of Astrophysics 2006. We attempt also to bring you updates on things of which there is currently only one (habitable planets, the Sun, and the universe) and others of which there are always many, like meteors and molecules, black holes and binaries. Keywords: cosmology: general, galaxies: general, ISM: general, stars: general, Sun: gen- eral, planets and satellites: general, astrobiology CONTENTS 1. Introduction 6 1.1 Up 6 1.2 Down 9 1.3 Around 10 2. Solar Physics 12 2.1 The solar interior 12 2.1.1 From neutrinos to neutralinos 12 2.1.2 Global helioseismology 12 2.1.3 Local helioseismology 12 2.1.4 Tachocline structure 13 arXiv:0705.1730v1 [astro-ph] 11 May 2007 2.1.5 Dynamo models 14 2.2 Photosphere 15 2.2.1 Solar radius and rotation 15 2.2.2 Distribution of magnetic fields 15 2.2.3 Magnetic flux emergence rate 15 2.2.4 Photospheric motion of magnetic fields 16 2.2.5 Faculae production 16 2.2.6 The photospheric boundary of magnetic fields 17 2.2.7 Flare prediction from photospheric fields 17 c 2008 Springer Science + Business Media. -

Bulletin Issue 29 Spring 2018 New Series by Paul Haley Begins in This Issue: 19Th Century Observatories 2018 Sha Spring Conference

BULLETIN ISSUE 29 SPRING 2018 NEW SERIES BY PAUL HALEY BEGINS IN THIS ISSUE: 19TH CENTURY OBSERVATORIES 2018 SHA SPRING CONFERENCE The first talk is at 1015 and the Saturday 21st April 2018 The conference registraon is morning session ends at 1215 Instute of Astronomy, between 0930 and 1000 at which for lunch. The lunch break is University of Cambridge me refreshments are available unl 1330. An on-site lunch Madingley Road, Cambridge in the lecture theatre. The will be available (£5.00) BUT CB3 0HA conference starts at 1000 with a MUST BE PRE-ORDERED. There welcome by the SHA Chairman are no nearby eang places. Bob Bower introduces the There is a break for refreshments Aer the break there is the aernoon session at 1330 then from 1530 to 1600 when Tea/ final talk. The aernoon there are two one-hour talks. Coffee and biscuits will be session will end at 5 p.m. and provided. the conference will then close. 10 00 - 1015 10 15 - 1115 1115 - 1215 SHA Chairman Bob Bower Carolyn Kennett and Brian Sheen Kevin Kilburn Welcomes delegates to Ancient Skies and the Megaliths Forgotten Star Atlas the Instute of of Cornwall Astronomy for the SHA 2018 Archeoastronomy in Cornwall The 18th Century unpublished Spring Conference Past and Present Uranographia Britannica by Dr John Bevis 13 30 - 1430 14 30 - 1530 16 00 – 17 00 Nik Szymanek Kenelm England Jonathan Maxwell The Road to Modern Berkshire Astronomers 5000 BC Some lesser known aspects Astrophotography to AD 2018 regarding the evolution of The pioneering days of Some topics on astronomers and refracting telescopes: from early astrophotographers, observations made from Lippershey's spectacle lens to the up to modern times Berkshire since pre-historic Apochromats times until last week An insight into the development of 2 the refracting telescope In this Issue BOOK SALE AT THE 2017 AGM Digital Bulletin The Digital Bulletin provides extra content and links when viewing the 4 Bulletin as a PDF. -

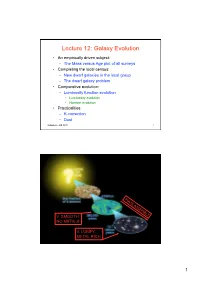

Lecture 12: Galaxy Evolution

Lecture 12: Galaxy Evolution • An empirically driven subject: – The Mass versus Age plot of all surveys • Completing the local census: – New dwarf galaxies in the local group – The dwarf galaxy problem • Comparative evolution: – Luminosity function evolution • Luminosity evolution • Number evolution • Practicalities – K-correction – Dust Galaxies – AS 3011 1 MASS ASSEMBLY V. SMOOTH NO METALS V. LUMPY, METAL RICH Galaxies – AS 3011 2 1 The Mass-Age plot 1. Completing the local census 2. Comparative studies Galaxies – AS 3011 3 Dwarf galaxies • Dwarf galaxies are a crucial part of the galaxy evolution puzzle but we know very little about them. • Main theory (see later) proposes that galaxies built-up from smaller units through repeated merging. • Numerical simulations typically predict several thousand dark matter haloes in the local group. • ~ 55 Local Group galaxies known. • ~ 1 new Local Group dwarf galaxy discovered every 18 months. • Very wide range of properties = a combination of late- starters, relics, debris and stunted systems. • Space-density extremely poorly constrained, I.e., important to appreciate that our current backyard census is woefully incomplete. Galaxies – AS 3011 4 2 2 New Local Group galaxies discovered recently… • Bootes • Mv=-5.7 mag • µo=28.1 mag/sq arcsec • Belokurov et al (2006) • Canes Venatici • MV=-7.9 mag • µo=27.8 mag/sq arcsec • Zuker et al (2006) Galaxies – AS 3011 5 The Luminosity-Surface Brightness Plane Galaxies – AS 3011 6 3 Comparative studies • Many comparisons are possible, e.g., – Profile shapes – Gas, dust, plasma and stellar content – Fundamental plane and Faber-Jackson relation – Tully-Fischer relation – Star-formation rates – Line indices, metallicity and colours – Morphologies and luminosity-size relations – Overall and component luminosity functions • Main issues are sample selection bias and demonstrating that a comparison of the high and low z samples is valid, comprehensive and complete.